Researchers have created a machine that tells you the nutrient density of various foods. Now they just need to define nutrient density.

It’s a warm morning in early June. You stroll to your neighborhood farmer’s market, ready to load up on the season’s first tomatoes. The vendors busy themselves replenishing their tables to keep the fruit stacked high. Scanning the displays of red slicers and rainbow-speckled heirlooms, the dizzying abundance of choices starts to stress you out. Then, you pull out a thin gray rectangular device from your pocket.

It’s no longer than a TV remote, and about half the width. You hold down the power button until you see the small LED screen light up. It is silent, lightweight, powerful in its capabilities. It is a spectrometer — an instrument that beams light into objects, measuring how it refracts at various frequencies, which helps to reveal the internal properties of those objects. The one you brought to the farmer’s market is specifically manufactured to assist in decoding the nutrient density of fruits, vegetables, and meat.

After waving the raygun like an incantation over an Amish farmer’s beefsteaks and some locally grown Early Girls, you land on the winner; a biodynamic farm’s Cherokee Purple tomatoes are loaded with the good stuff: lycopene, potassium, and folate. At five dollars a pound, these guys are worth their steep asking price.

Say What?

A prototype of this very tool — called the Bionutrient Meter — was developed in 2017. The project was spearheaded by The Bionutrient Institute, a nonprofit focused on nutrient density research, working in collaboration with an open-source agricultural research company called OurSci. Nutrient density, put simply, refers to “the relative amount of nutrients per calories” of any given food.

The science employed by the meter is called spectroscopy, defined by NASA as “a scientific method of studying objects and materials based on color. More specifically, spectroscopy involves analyzing spectra: the detailed patterns of colors (wavelengths) that materials emit, absorb, transmit, or reflect.” Spectroscopy is used in a range of applications, from the analysis of starlight (hence: NASA) to tracing chemical pollutants in our environment.

Well before the advent of spectroscopy and other modern scientific techniques of nutrient profiling, people have understood that different types of foods have different nutritional properties. Legumes are loaded with protein, leafy greens offer abundant fiber, red meat is rich in iron, and on and on.

While the appreciation of the nutritional differences between food groups is uncontroversial, emerging scientific inquiry is trying to get to the bottom of a less clear-cut hypothesis: that there are noteworthy nutritional discrepancies within specific foods. In other words, maybe the apple you picked from your grandmother’s backyard has more potassium and vitamin C than the apple from your favorite farmer’s market booth (or vice versa).

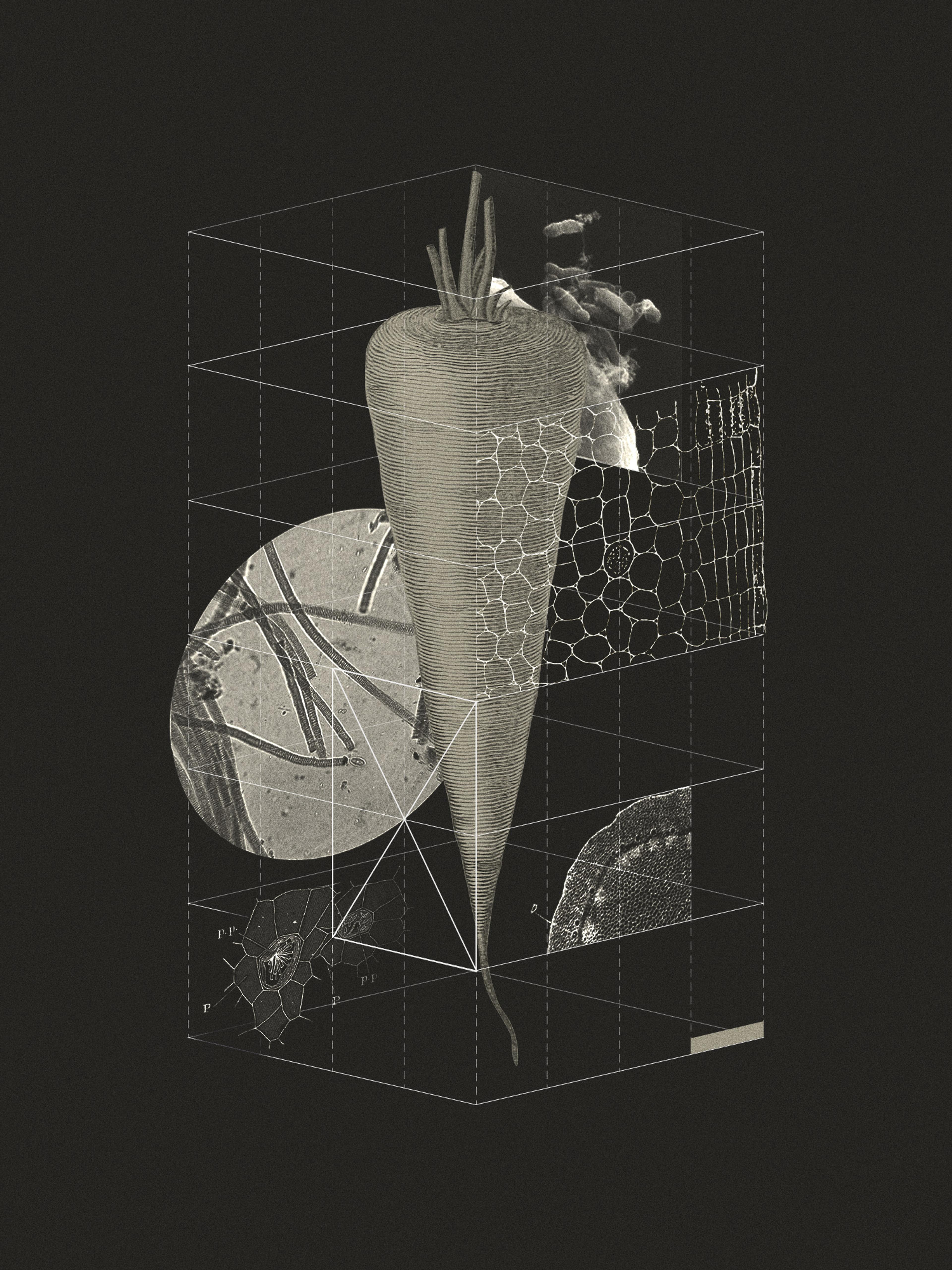

The evidence seems to bear this out. Varying levels of vitamins and other micronutrients can be observed in the carrot crops grown at Pete’s Farm versus Mary’s Farm. (“Carrots” here is simply a shorthand placeholder for all manner of vegetable and fruit crops.)

Defining the Perfect Carrot

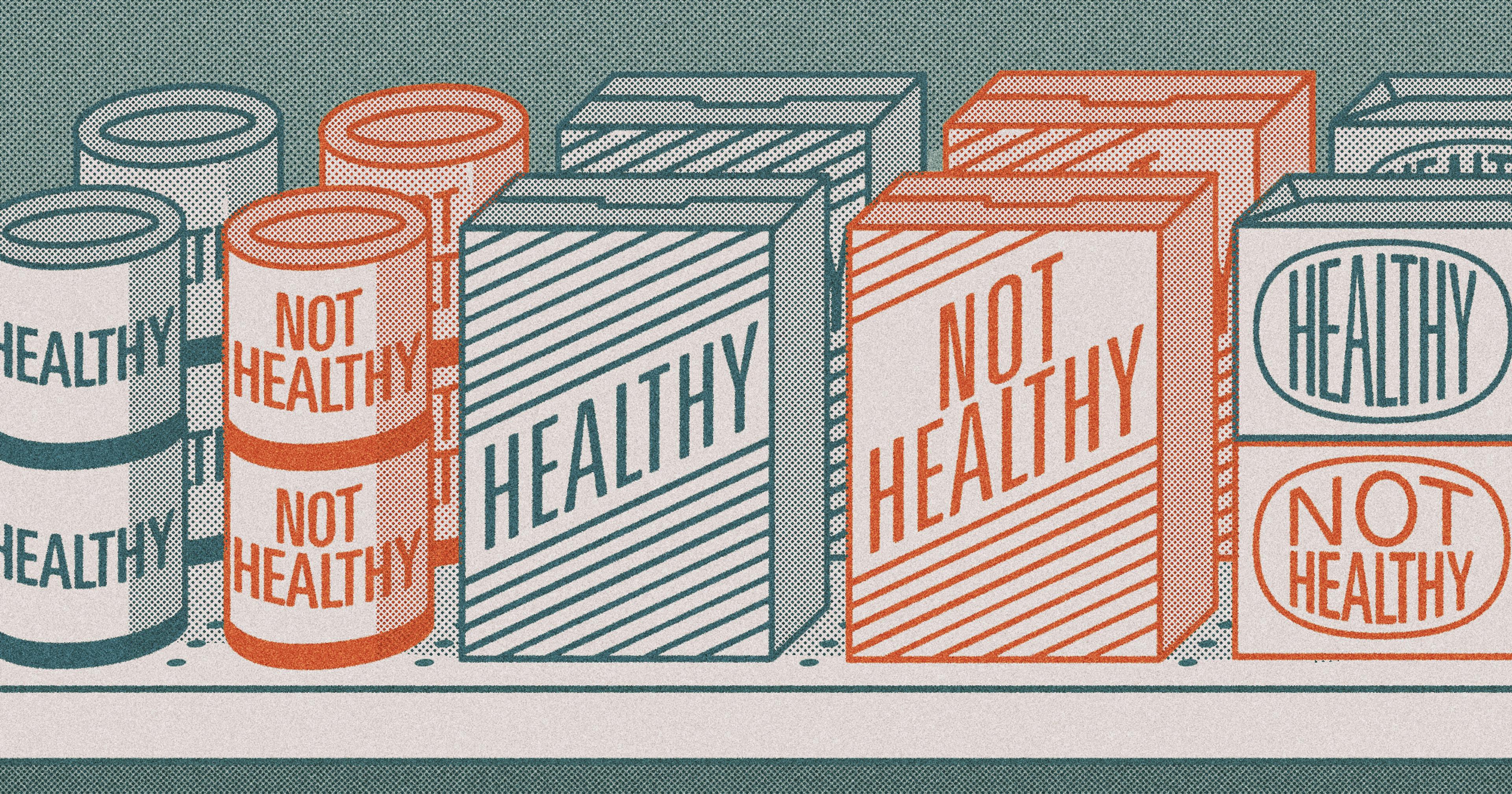

Less clear is what we should consider a commendable amount of vitamins and micronutrients in a standalone carrot — without having to scan every carrot at the farmer’s market with a spectrometer to gather comparative data. The BNI paused production of the Bionutrient Meter in 2022 to drill down on this issue. As Kittredge put it to me, “Now I have to figure out: What is nutrient density? Because you can’t build a meter that’s calibrated to tell you nutrient density levels until you figure out what nutrient density is.”

To that end, he and his team are now working to develop a measurable 1-100 scale of nutrient density that can be applied to common foods. They aim to calibrate this scale to be applicable to twenty crops — like apples, chickpeas, and yes, carrots — by 2028.

Although there is growing consensus that not all carrots are created equally, not everyone in the food science world thinks that these nutritional differences are worthy of much attention. Kevin Folta, one such skeptic and a horticultural scientist at the University of Florida, is wary of claims that point to a wide variance in nutrient density between one crop of wheat (let’s say) and another crop of wheat grown under different circumstances.

“When you’re talking about nutrient density,” he explained, “the differences are not 500 times difference or five times difference. It’s usually a little bit different one way or the other.”

“You can’t build a meter that’s calibrated to tell you nutrient density levels until you figure out what nutrient density is.”

(Folta faced controversy in 2019 when he brought a defamation lawsuit against The New York Times, claiming that the newspaper had unfairly characterized his research as being paid for by Monsanto. He ultimately lost that lawsuit.)

Furthermore, it does not appear that a plant’s macronutrients — its proteins, carbohydrates, and fats — vary all that much from one crop to the next. These organic compounds make up the most essential building blocks of life. You can rest assured that the fiber found in your own garden’s kale is comparable to the kale in the produce aisle, which is comparable to the hydroponic kale at the farmer’s market, and so on.

Stephan van Vliet, nutrition scientist at Utah State University and a research collaborator with the BNI, acknowledges this general uniformity of macronutrient levels within any particular fruit or vegetable. It is in the vast sea of micronutrients and bioactive compounds where Vliet and his colleagues find differences worthy of attention. He calls this botanic territory the plant’s “dark matter.”

It does not appear that a plant’s macronutrients — its proteins, carbohydrates, and fats — vary all that much from one crop to the next.

Here we find polyphenols, flavonoids, minerals, and vitamins (van Vliet estimates a single plant can contain thousands of these compounds). Some of these compounds — particularly, the phytochemicals — are known as secondary metabolites. This class of organic compounds are not critical to an organism’s basic development, but do confer protective traits that can help with survival and reproductive capabilities.

When humans eat plants that have produced a lot of secondary metabolites, we process these compounds as antioxidants. In this way, their role in plants as self-defense agents continues after they have been metabolized in our own bodies.

For Kittredge and van Vliet, it is the variability in secondary metabolites and other micronutrients within crops, and what that could mean for human health outcomes, that excites them. It is their mission to track down the gold standard of carrots, the paragon of sweet potatoes, the top-shelf tomato.

Going Back to the Source

Now, the question becomes: “What agricultural factors contribute to the diverging micronutrient densities found in one crop of carrots versus the next, and how do we replicate these growing conditions to consistently produce the most nutritious vegetables and fruit?”

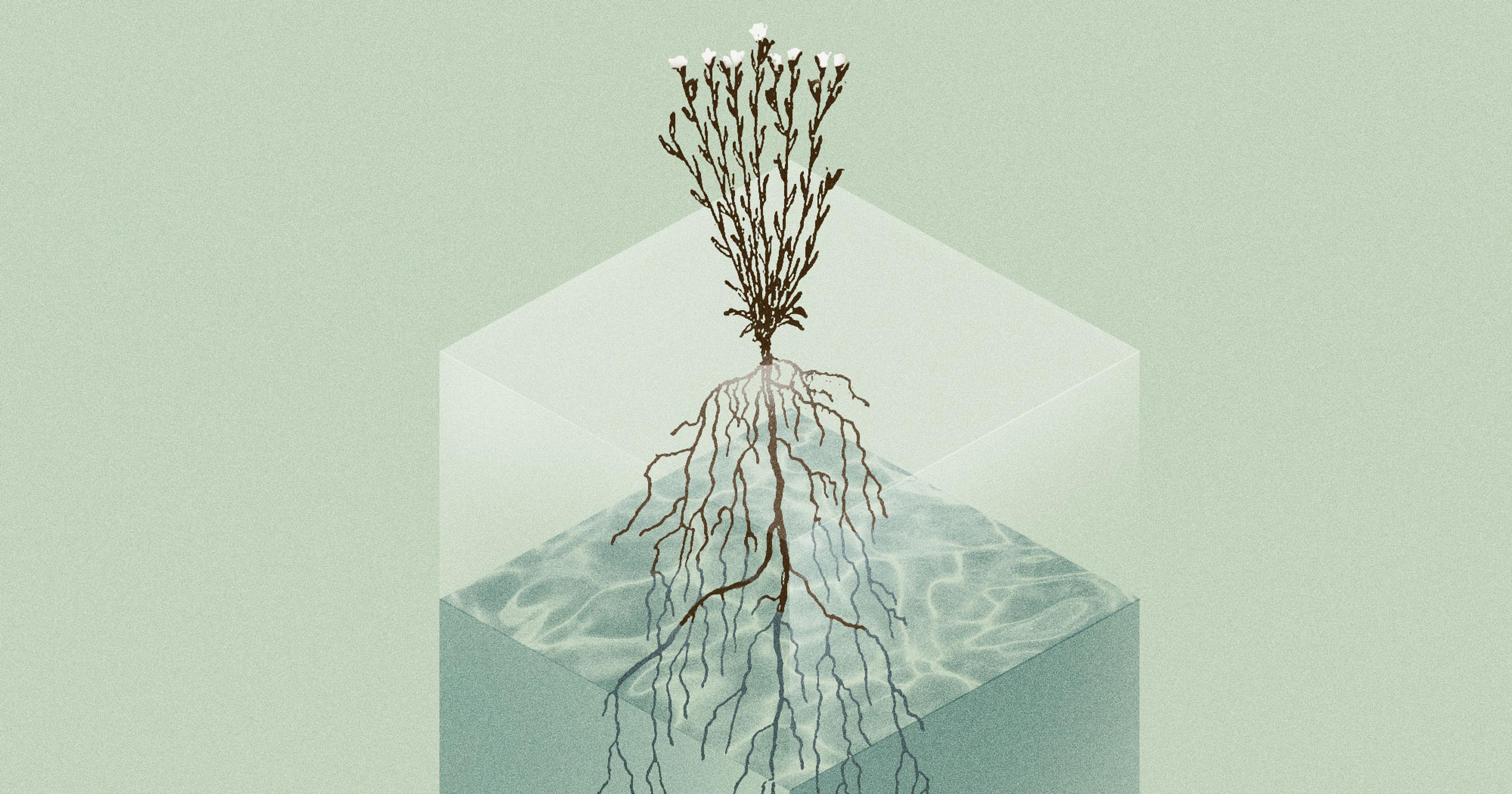

Traditionally, scientists have attributed nutrient density discrepancies to what is known as the genotype x environment x management equation. This school of thought chalks up a nutritionally superior crop of wheat’s superiority to a combination of genetics, climate, and how the farmer cared for it from seed to harvest (the fertilization regimen, irrigation techniques, cover cropping practices, etc.). Notably left out of this formula is soil health as a standalone consideration.

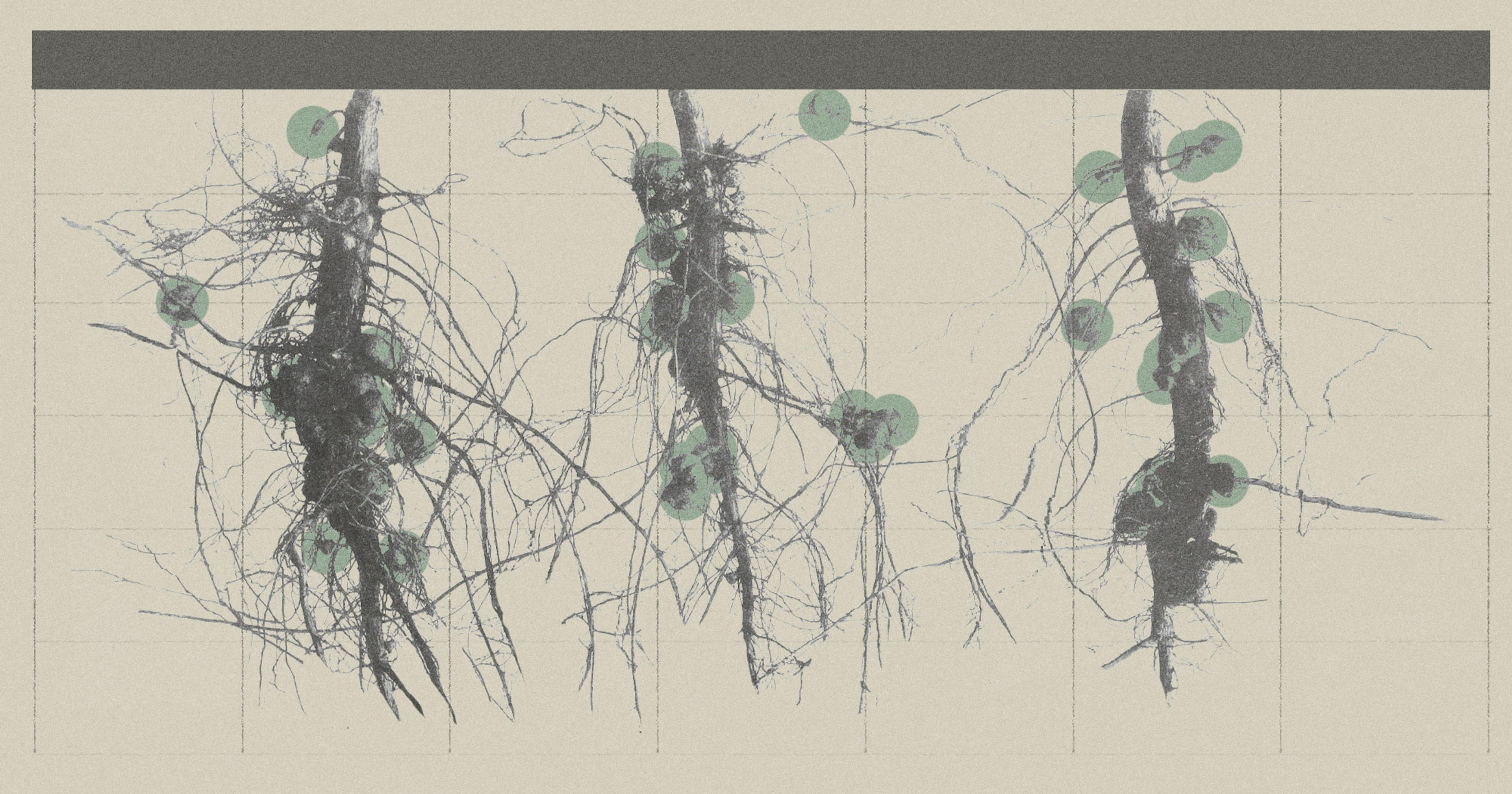

A growing cohort of agronomists are turning a curious eye to the soil biome and the effects it may have on crop nutrition — a number of studies have come out in the last decade or so showing that soils with high levels of organic matter and robust communities of microorganisms tend to produce crops with increased nutrient density.

Still, there remain skeptics in the field who view that outermost layer of earth as not much more than a substrate for the cultivation of vegetables, grains, fruits, and forage. Folta, for his part, told me bluntly: “I’m not a soil worshiper.” For him, the correct dosage of fertilizer throughout a crop’s lifecycle is probably the most important factor in determining its nutrient density — not the overall health of the soil ecosystem that absorbs and transports that fertilizer.

Van Vliet disagrees with this assertion of insignificance. Perhaps most notably, he has found in his research that biodiverse agricultural systems generally produce crops with thicker densities of secondary metabolites — the class of compounds that help both plants and their human consumers in fighting off disease. “Many of those compounds also are natural pesticides,” he said, “so if you’re providing those to the plant, there’s no reason for the plant to make those and you end up with plants that are lower in phytochemicals.” In other words, he says, if you “provide a lot of fertilizer to the plant, you get more of a lazy plant.”

Now, the question becomes: “What agricultural factors contribute to the diverging micronutrient densities found in one crop of carrots versus the next?“

Van Vliet is careful to point out that, while it can be shown under a microscope that crops grown in regenerative systems often produce higher levels of phytochemicals, what is less clear is if consumers who eat those plants are actually healthier than those who eat conventionally grown produce. His lab conducted a randomized control trial comparing the health outcomes for three groups of people: those who ate a standard American diet rich in processed foods, those who ate primarily a diet of whole foods from the conventional aisles, and those who mostly ate a diet of whole foods grown on regenerative farms.

He explained that, “While the regenerative group improved their health a little bit quicker than the conventional group, [the conventional group] still got a lot healthier compared to the regular ultra-processed group.” It looks like the gap between a Cheeto and a conventionally grown parsnip is much wider than what separates a vegetable grown with synthetic inputs and its organic counterpart.

While the Bionutrient Meter was able to read the levels of phytochemicals in a carrot, the question then follows: Without a conclusive picture of how these phytochemicals affect human health, will consumers buy the meter at scale? The prototyped tool hit the market at $377. By December 2021, around 150 units had been sold.

The Bionutrient Institute has hopes to one day sell the device for $100. Perhaps a reduced price might translate to increased sales. And maybe wider adoption of the meter could then lead to a larger dataset that is needed to probe answers from the complicated nexus of soil biology, nutrient density, and human health.