Climate change is devastating coffee production worldwide. Can it take root in Florida?

If you’ve ever bought a bouquet of flowers, chances are the green fronds placed among the blooms came from Pierson, Florida. This sleepy town of 1,500, sprawled out along Highway 17 about halfway between Jacksonville and Orlando, bills itself as the “Fern Capital of the World,” and for good reason: The area around Pierson supplies 97 percent of the leatherleaf ferns in the U.S., the most popular variety for floral arrangements.

Ferns in Pierson are typically grown outdoors to take advantage of central Florida’s slightly acidic soil and warm, humid climate, but they also require artificial shade structures or large trees to protect them from the relentless sun. When Felipe Ferrão, a plant researcher at the University of Florida, first came to Pierson in 2023, he immediately thought that these shaded areas would be ideal for another kind of crop: coffee.

This year, Ferrão is planning on testing out this hypothesis by brewing his first batch of coffee from field-grown Florida beans, which he plans to harvest from a half-acre plot on a fern farm in Pierson. He hopes to demonstrate that Florida can nurture a homegrown coffee industry, providing a domestic supply of the crop at a time when climate change is devastating coffee plots in countries like Brazil and Kenya.

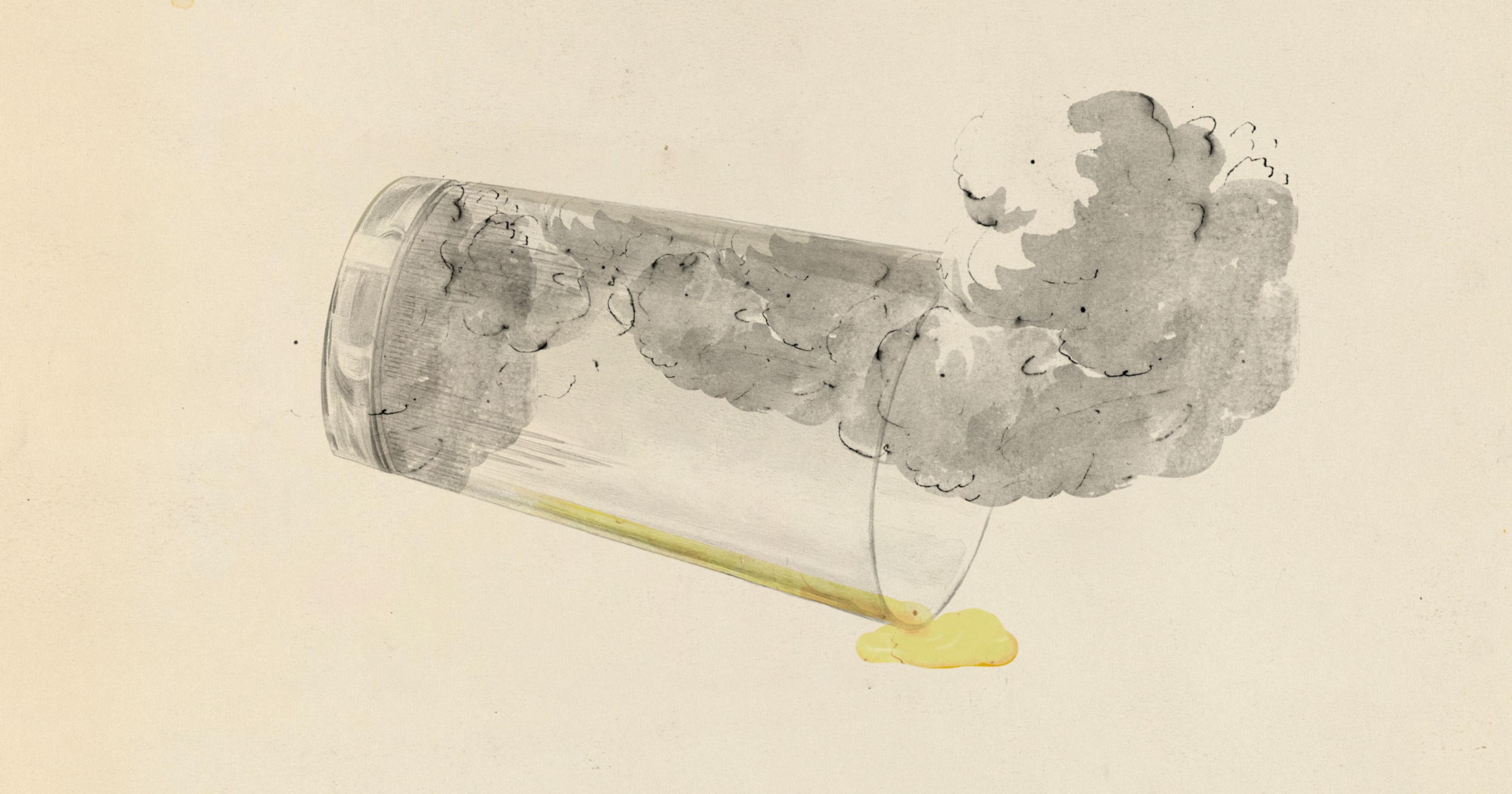

“We are the country that consumes the most coffee in the world,” Ferrão said. “If we think about the fact that by 2050, more than 60 percent of coffee production around the globe is going to decline, there is no way that this country won’t be affected.”

Florida is better known for its citrus industry, which once thrived in the state’s abundant sunshine but has declined by over 90 percent in the last two decades due to more extreme weather and the spread of citrus greening disease. When Ferrão started working at the University of Florida as a postdoc in 2017, his goal was to study how genomics and plant breeding could be used to develop new kinds of agricultural industries in the state, starting with blueberries. Ferrão comes from a long line of coffee farmers in Brazil, the world’s largest coffee producer, and he eventually began thinking about what it would take to grow the crop in Florida.

To find funding and institutional support for the project, Ferrão approached the University of Florida’s Tropical Research And Education Center, where since 1929 specialists have studied how to grow all kinds of tropical fruits, vegetables, and ornamental plants, from passionfruit and papayas to lychees and limes. They breed different varieties to develop ones that are most adapted to the climate and try to work out solutions for diseases and pest control issues, said Jonathan Crane, the center’s associate director.

“People have tried to grow coffee down here for many years and have not been successful,” Crane said. “They didn’t have the knowledge to grow it successfully, or they picked the wrong species or variety of coffee.”

Temperatures played a role, too. Coffee originates from the Ethiopian highlands and has been introduced to countries like Brazil, Vietnam, Costa Rica, Kenya, and Colombia, all located close to the equator between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, an area known as the “coffee belt.” The climate here is mild and typically doesn’t swing into extremes, which is how coffee plants like it. Coffea arabica, the most popular variety, thrives in a temperature range between 64° and 70°F.

“People have tried to grow coffee down here for many years ... they didn’t have the knowledge to grow it successfully, or they picked the wrong species or variety of coffee.”

Though Florida is usually warm and sunny, because it lies north of the coffee belt it can occasionally experience freezing temperatures (leading to headlines about iguanas falling out of trees). When Florida growers last attempted to plant coffee in the 1940s, Crane said, it “got frozen out,” unable to tolerate temperatures in the 40s and 50s.

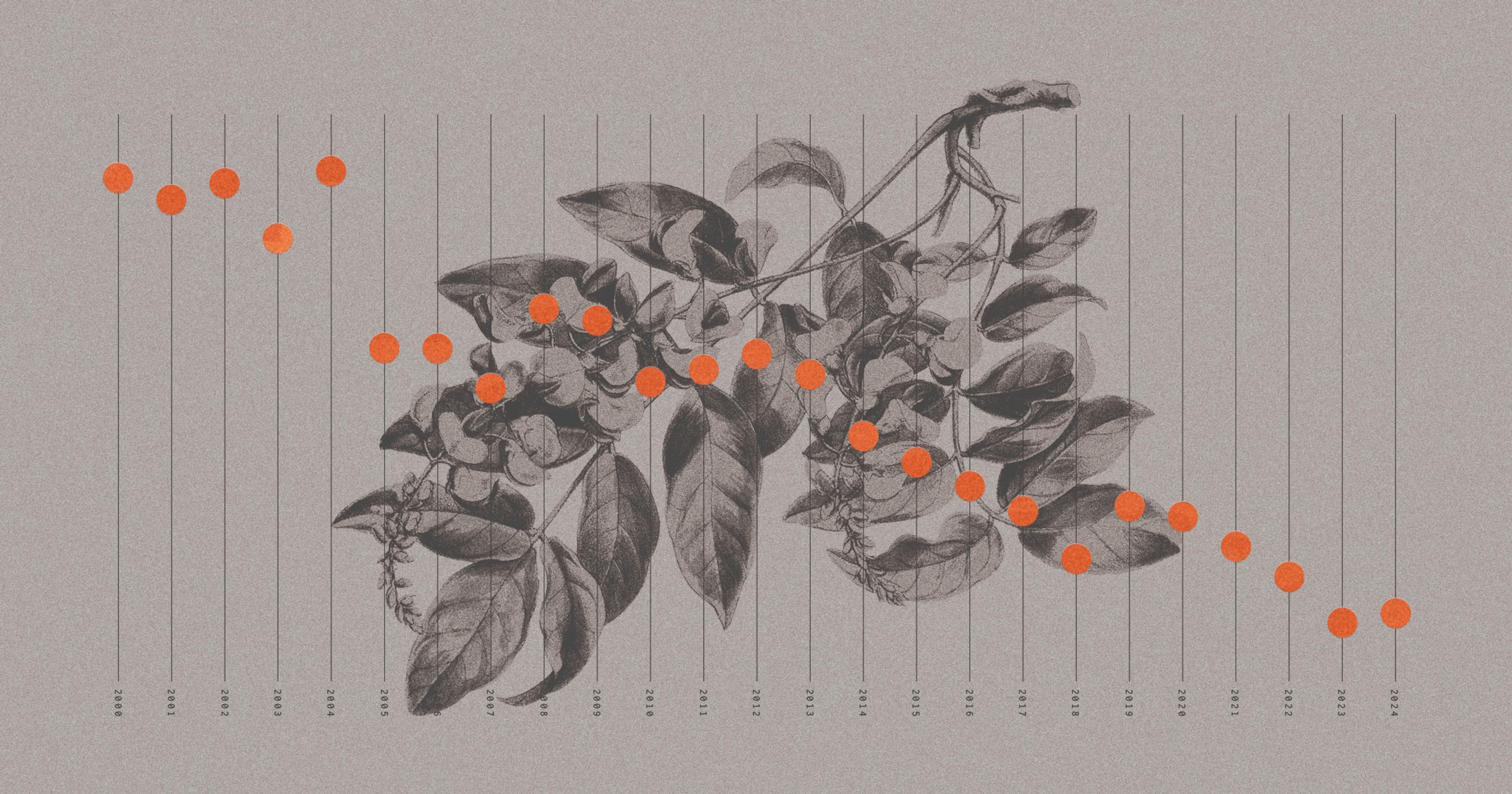

Florida’s changing climate, though, could mean it’s time to give coffee in the state another try. Average annual temperatures in the state have increased by 3.5° F since 1950. Although Florida still experiences winter cold snaps, the number of freezing events per year has sharply decreased, Crane said, allowing agricultural production to move northward. And it’s opening up the possibility of growing some crops, like coffee, that struggled to survive when temperatures were colder.

Ferrão is also experimenting with growing a different variety of coffee — Coffea canephora, also known as robusta — that’s more heat- and pest-resistant than the popular arabica. And aside from producing homegrown coffee, Ferrão’s research focuses on understanding the genetics of coffee plants in order to breed more resilient, flavorful, and high-yielding varieties — not just in Florida, but around the world.

“We can deliver new tools [to growers], discover new trends and answer important biological questions,” Ferrão said. “All this expertise can help breeders and other institutions to improve the sustainability of the coffee chain.”

The work in Pierson began two years ago, when Ferrão was contacted by Gineva Peterson, a Pierson resident whose family has been running a fernery there since the 1970s and who wanted to branch out into growing coffee but couldn’t afford the start-up costs. She offered her land in exchange for Ferrão’s plants and expertise, and since May of last year they’ve planted around 600 arabica and robusta seedlings, which they anticipate will produce enough beans to host a coffee tasting by the end of the year.

“The majority of people in the U.S. have not seen a coffee tree.” She thinks they’ll come to Florida “just to experience what a coffee tree looks like.”

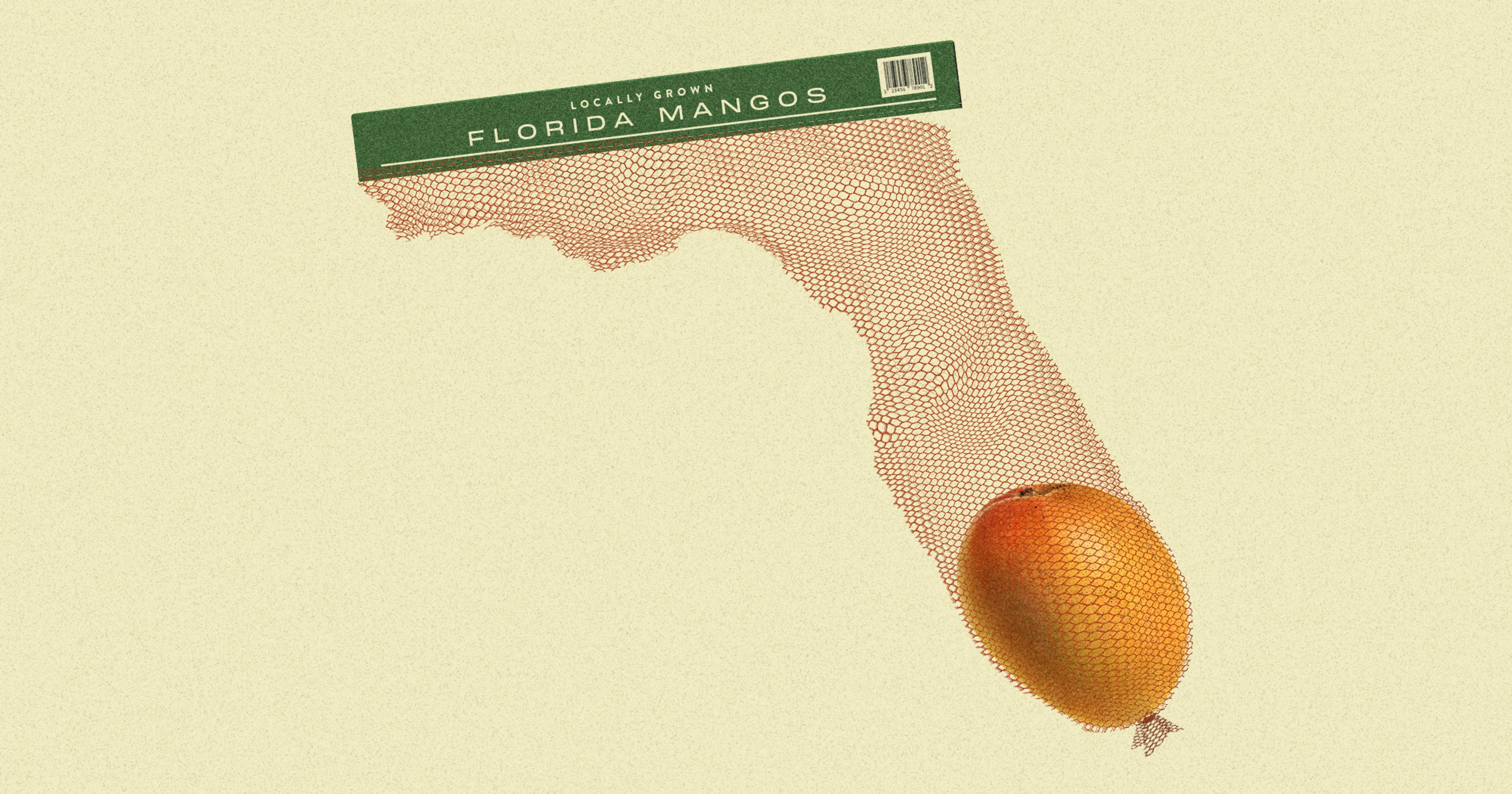

Peterson’s eventual goal is to run a coffee shop supplied entirely by her home-grown beans. Though it would be a Florida first, coffee production has also taken root in southern California, where a cooperative of 65 small farmers called Frinj is growing on a commercial scale. Crane sees potential for family farms and small growers to similarly make a living selling specialty, “Florida coffee”-branded beans.

“It’s not like we’re going to become a major coffee production area for the world like Brazil or Vietnam,” Crane said. Instead, “there is a huge interest and potential for a niche, high-end, valuable coffee industry.”

He brought up the example of Kona coffee, which was introduced to Hawaii in 1829 and grows only on around 9,000 acres on the slopes of the Hualalai and Mauna Loa mountains. One of the most expensive coffees in the world, it averages around $20 per pound and can get up to $60 or more. Educated consumers who have developed specific tastes in coffee, Crane said, are willing to pay a premium for specialty brands; other income can come from agrotourism, where people visit coffee farms and see how it’s grown and roasted.

The coffee plants have had to adjust to Florida’s sandy soil, and those grown under shade structures needed to be protected from freezing. Eventually, Peterson hopes to transition away from shade structures entirely and instead plant coffee underneath groves of oak trees in an arrangement known as a “hammock,” which also naturally keeps them warm in the winter. Insurers have stopped covering shade structures in the last few years, Peterson said, claiming they were too vulnerable to destruction from hurricanes.

Though Peterson doesn’t see coffee replacing ferns entirely, she believes the additional crop can help diversify the agricultural industry in central Florida. She anticipates she’ll have enough beans to open her coffee shop within one to two years. And once she and the University of Florida researchers have finalized their coffee-growing technique, other growers in Florida can participate, too.

“The majority of people in the U.S. have not seen a coffee tree,” Peterson said. She thinks they’ll come to Florida “just to experience what a coffee tree looks like.”