Farmers, entrepreneurs, and scientists consider a saffron industry in the U.S. — but is there a market?

Every gold rush needs its proverbial shovel salesmen, even when the wealth in question lies above the soil. The bonanza Eric Meltzer and Byron Boos hope to facilitate comes in the form of hairlike, half-inch, reddish-orange threads: the stigmas of a small purple flower that, when dried, become the most expensive spice in the world.

The two are partners in Pennsylvania Saffron, LLC, which operates a research farm about 50 miles northwest of Philadelphia in the small community of Barto. Although the company harvested over 83,000 saffron crocuses from its one-acre plot last year, founder Meltzer said farming the flowers is mostly a means to a greater end.

“Our goal isn’t to be saffron farmers, but to be a technology company that solves the problem of mechanizing it,” explained Meltzer, who came to the crop in 2022 after selling his stake in a prior business. “We’re trying to make it so small American farmers can make money growing saffron, doing it in a way that’s different from how it’s been done since the time of the Bible.”

Saffron’s high prices — a half-gram retails for $14, or nearly $12,700 per pound, through Pennsylvania Saffron’s website — have long been tied to its intensive production. Traditionally, to avoid damaging the delicate flowers, each crocus is picked and has its three stigmas removed by hand. It can take 150 flowers to yield one gram of finished spice.

While the colonial U.S. once enjoyed a domestic saffron industry (coincidentally anchored in Philadelphia and supplied by nearby Pennsylvania Dutch farmers, who exported the crop to Spanish colonies in the Caribbean), it dwindled away after British disruption to trade routes during the War of 1812. We currently meet its saffron demand through imports, over 54 tons in 2024, from places with lower labor costs.

(Iran produces about 90% of the world’s saffron, but much of it is reimported through Spain or other countries to circumvent U.S. sanctions. Afghanistan, India, and Greece are among the other leading growers.)

Boos, Pennsylvania Saffron’s chief operating officer, envisions American saffron producers finding a toehold in the domestic market through greater automation at every step. He’s been engineering a modified garlic planter to put crocus corms in the ground, a motorized harvesting platform to speed a worker’s progress through the field, and mechanical systems for separating the stigmas from the flowers.

“We’re basically developing a playbook for farmers, so if you want to grow saffron, this is where you start,” he said. “But because we haven’t grown it before, every one of the elements is unproven. It’s a little daunting.”

“Because we haven’t grown it before, every one of the elements is unproven. It’s a little daunting.”

Even without specialized equipment, a growing number of U.S. farmers have been staking their own claims on saffron’s golden vein. The crop’s domestic resurgence traces to 2015, when University of Vermont entomologist Margaret Skinner partnered with one of her postdoctoral researchers, Arash Ghalehgolabbehbahani, an Iranian who was curious if the crop could grow in his new home. To their surprise, the plant proved remarkably resilient and produced solid, high-quality yields.

Ghalehgolabbehbahani and Skinner went on to establish the North American Center for Saffron Research and Development at UVM and held their first saffron-growing workshop in 2017. The center now boasts over 800 members on its SaffronNet listserv, and its most recent workshop, held earlier this month, had over 100 registrants from 25 different states. Commercial saffron operations have popped up in Vermont, Texas, California, and Washington. Skinner says hobby growers are successfully raising the plant as far afield as Alaska.

She sees saffron as a particularly great fit for small-scale, diversified farms like those that proliferate in Vermont: Although harvesting takes a burst of hard work, she says, it’s squeezed into a couple of weeks in late fall, when most other crops are done for the year. And because the spice is dried, farmers can store it and make sales over time, potentially supplementing their income during leaner seasons.

Mechanization of the type Pennsylvania Saffron is pursuing could be helpful for those farmers, but bigger barriers to domestic saffron may lie downstream of growing the crop. Rebecca Brown, a researcher at the University of Rhode Island who’s experimented with saffron, said that drying the spice is technically considered food processing. State-level regulations that weren’t designed with saffron in mind can demand cumbersome compliance paperwork or require a sterilizing “kill step” that would destroy its delicate flavors.

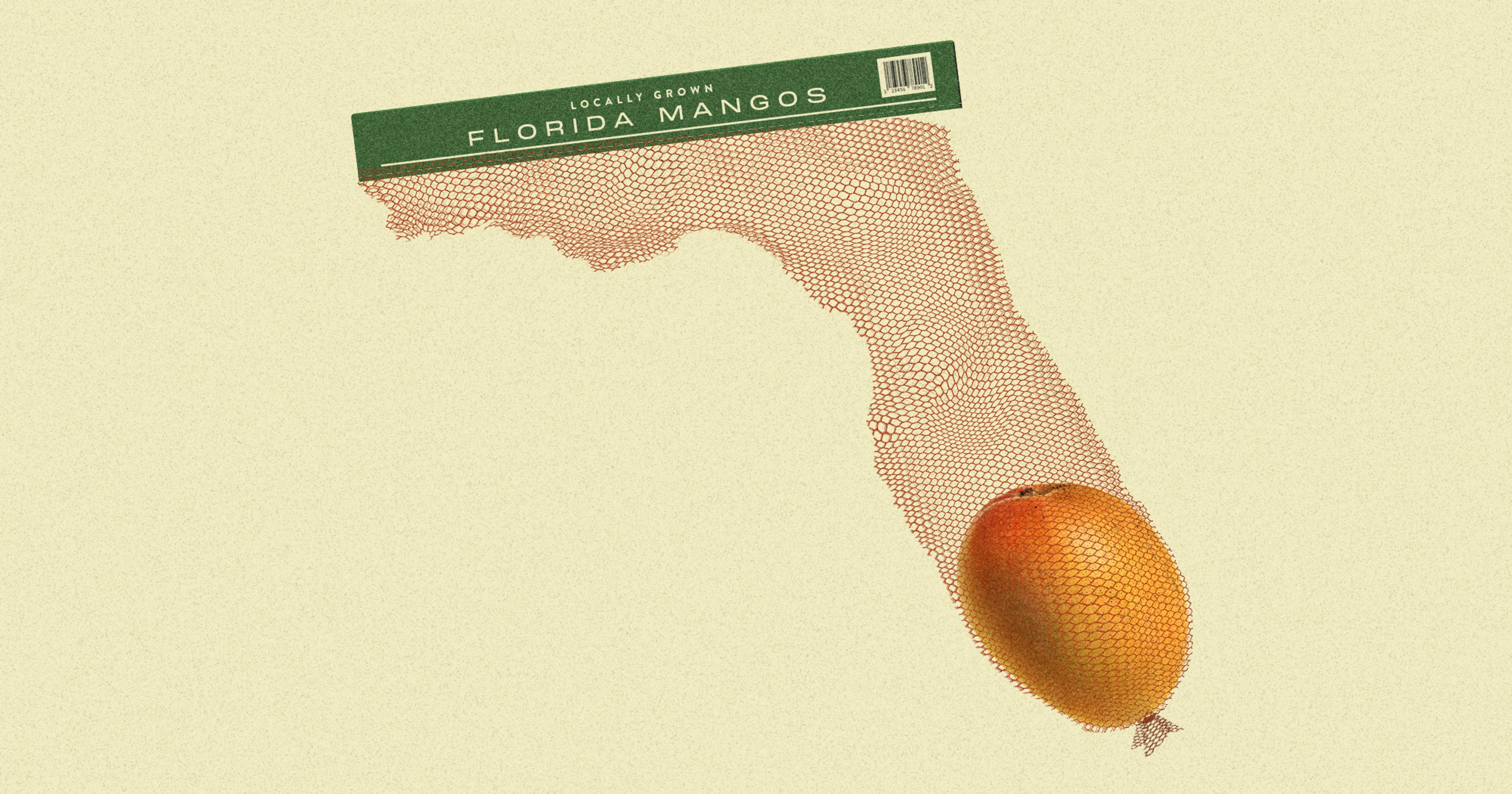

Finding a market also remains a major challenge. U.S. growers can’t compete on cost with even the most expensive imported saffron; Antonio Sotos, who exports the coveted La Mancha variety from Spain, says he pays farmers the equivalent of about $2,500 per pound. Although the Trump administration has generally increased tariffs on saffron-exporting countries, those rates aren’t anywhere near enough to close the price gap with domestic saffron.

“Our goal isn’t to be saffron farmers, but to be a technology company that solves the problem of mechanizing it.”

Ethan Frisch, co-founder and co-CEO of online spice company Burlap & Barrel, said he’s explored adding U.S.-grown saffron to his lineup. But the selling point of domestic sourcing, he continues, isn’t enough to justify the much higher cost. He also wants to keep supporting the female Afghan farmers who currently supply his saffron, for whom agriculture is among the few income-generating activities permitted by the country’s Taliban-led government.

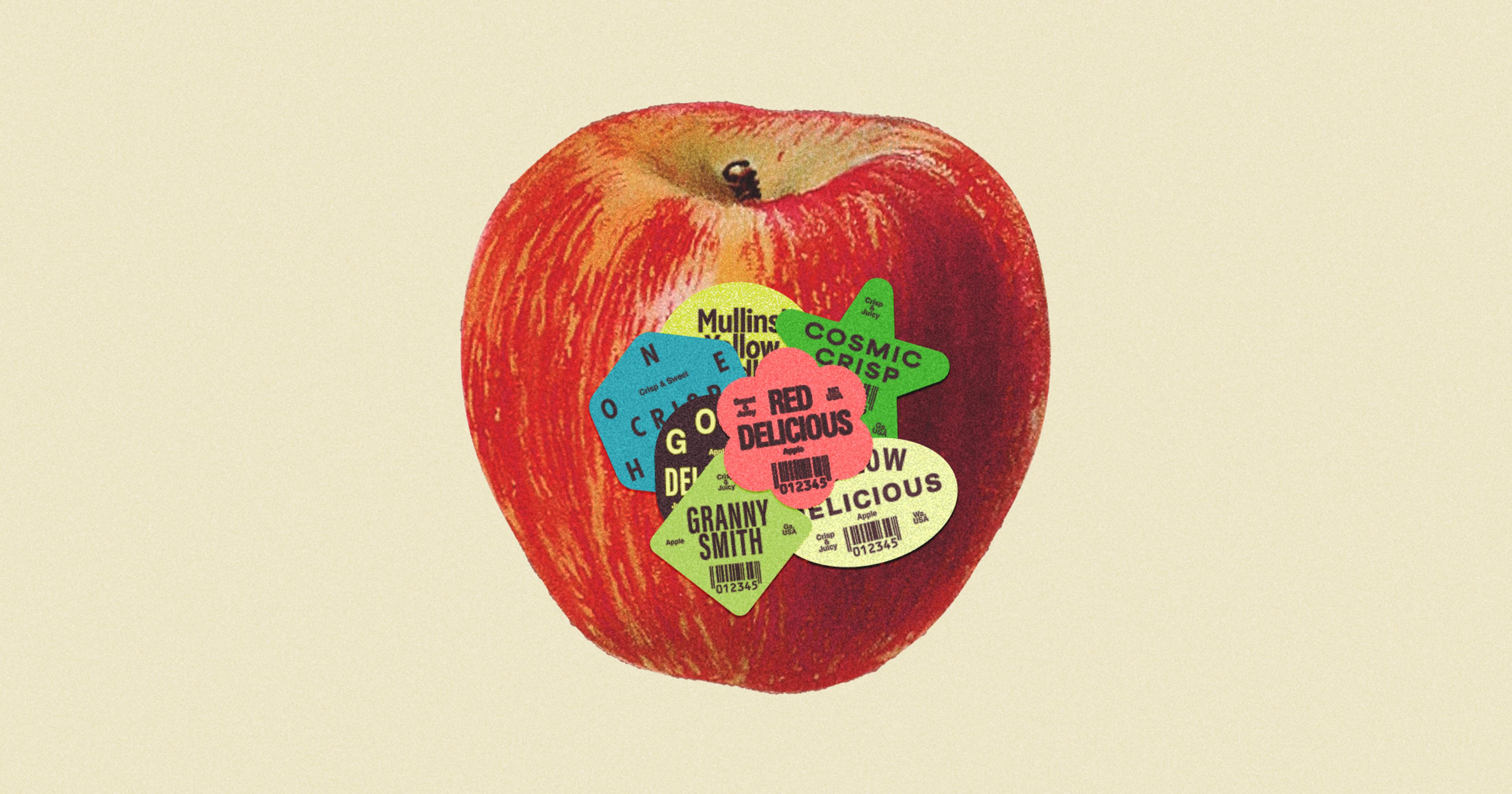

“Customers are reluctant to buy saffron in the first place,” Frisch said, with the notable exceptions of the Indian and Iranian diaspora, who value its subtle, floral, honey-like flavors in dishes like Persian rice and paella. “In my experience, most European-background Americans are not cooking with saffron on a regular basis, and trying to get them to has been a huge challenge.”

While some U.S. saffron growers have been able to market directly to customers, charging between $50 and $75 per gram — up to $34,000 per pound — volumes remain low. Other marketing possibilities include value-added products, like infused honeys and maple syrups, or the pharmaceutical industry, where saffron has been studied as a treatment for conditions like premenstrual syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression. (Traditional medical systems like Ayurveda have also claimed the spice to be a potent aphrodisiac.)

Meltzer with Pennsylvania Saffron agrees that the industry is at best embryonic. “We certainly don’t want to solicit people to pour all their money into pickaxes,” he said, returning to the gold rush analogy. “We don’t have a complete answer yet.”

But he and Boos are hopeful that the time will soon be right for American farmers to dig in. They point to the rise of foodie culture, a growing desire for local sourcing, and visual-driven social media that might reward saffron’s striking hues.

“People are using things that are unique and different,” Boos pointed out. “Well, saffron is the most unique and the most different.”