Wildfires have become the new norm in the Pacific Northwest — where most of our hops are grown. Researchers are digging into the short- and long-term effects.

On Labor Day weekend 2020, multiple wildfires broke out across Oregon. When it was all over, they had killed 11 people, burned more than 1 million acres, and blanketed the entire region in apocalyptic levels of smoke.

It was the worst spate of wildfires the state had ever seen, and it marked a significant shift in Pacific Northwest agriculture. In the five years since, wildfire smoke has become a persistent fact of life in the region, impacting not just the people who live there but the crops that are grown.

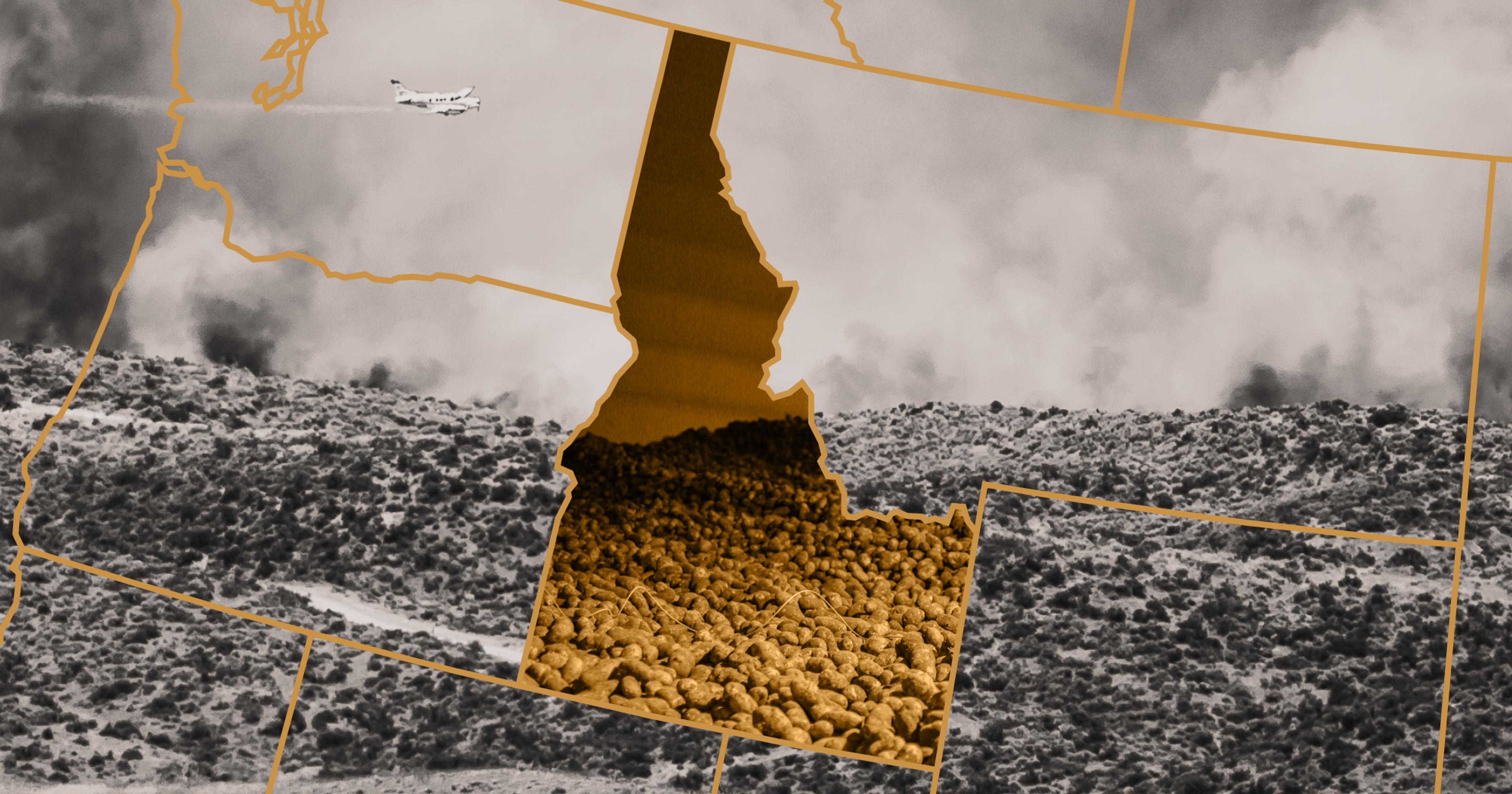

Hops are a crucial part of the region’s agriculture — more than 98% of U.S. hops are grown in the Pacific Northwest, with a 2024 farm gate value of $450 million, according to Maggie Elliot, science and communications director for Hop Growers of America, an industry group. They are also particularly susceptible to smoke taint.

While the 2020 fires were immediately concerning for wine grapes, there was initially less attention paid to hops. So Tom Shellhammer, professor of fermentation science at Oregon State University (OSU), set out to change that. Since 2022, Shellhammer has received around $250,000 in funding from the Hop Research Council to study how wildfire smoke affects hops — and, by extension, how it impacts the taste of beer.

As climate change has made wildfires more frequent and more intense, it’s increasingly important to understand how the plants and the resulting beer are affected. “Smoke has been persistent enough with hop growers that it’s not an occasional thing,” said Shellhammer. “It’s almost like a smoke season.”

If you drive through certain regions in Oregon, Washington, or Idaho, you’ll likely see fields of hops. Grown on a trellis system, the delicate-looking strands, called bines, stretch 18 feet in the air and wind along the upper wire. Each bine can yield more than 1,000 cones, which look a little like a miniature green pinecone, except light and papery and just an inch or two long. What growers are after is the lupulin inside the cone, which contains the resins and aromatic oils that give hops their bitterness, aroma, and flavor. (They’re also what can make hops smell like weed, as they share some similar compounds.)

After being harvested (typically from mid-August to mid-September), they’re taken almost immediately to the kiln to be dried, which happens onsite at the farm. These spaces are typically around 1,000 square feet and a farm will have many of them onsite; some growers can process up to 100,000 pounds of hops a day. The cones come in with about 80% moisture and are spread out onto a massive cloth bed. Hot air is then pumped into the building until the hops are dried to 8-12% moisture, which typically takes 6-8 hours.

If the air outside is smoky, it gets pumped in and essentially blasted right at the cones. “This crop that you’ve cultivated for the year is now, because of the weather, at a very high risk of being rejected due to smoke taint,” said Elliot.

After hops are dried, they’re typically sold to a hop merchant, who turns the bales into pellets or extracts and sells them to brewers, who use hops at two stages. Most add it when they’re boiling the wort (the sugary liquid that comes from grain); this adds a bit of flavor but is primarily used for bitterness. But if brewers are looking for intensely aromatic or really hoppy beers, they also add it after fermentation, essentially making “a hop tea with beer,” Shellhammer said.

If hops smell smoky, they can be rejected, which means farmers must try to recoup their losses through crop insurance, said Max Coleman, farm operations manager at Coleman Agriculture, which has had bales rejected for smoke taint. “Sometimes farmers can get a reduced price rather than an outright rejection, but you definitely make quite a bit less money.”

There aren’t industrywide numbers on how many hops are rejected because of smoke damage, but Elliot said that after 2020, farmers started “ringing alarm bells.”

Right now, it’s more about planning for eventualities, Shellhammer said. “The losses have been real, but not devastating,” he said. “The industry knows that it’s going to be a persistent problem. They just don’t know how much.”

Shellhammer has been working with a handful of farms in the Pacific Northwest to test three stages in hop development: the impact of smoke while hops are still growing, the impact while they’re being dried, and how smoky hops affect the brewing process.

To test hops in the field, he and his team built a greenhouse-like structure over the hop plants and pumped in smoke from a Traeger grill. For this phase, they worked with two Oregon farms: Coleman Agriculture, which is the state’s largest hops producer, and Westwood Farms.

For the drying phase, Shellhammer took a similar approach, using a grill to pump smoke into a pilot kiln at Elk Mountain Farm in Idaho, which supplies hops to Anheuser-Busch.

It’s still too early to be definitive, especially since both sets of experiments were done in controlled environments, but Shellhammer feels reasonably confident that the kilning phase is when the hops get the most smoke exposuret. “It’s sort of logical,” he said “If you think about really peaty Scotch whiskeys, during the drying process, they pump a bunch of smoke through it.”

There’s potentially a silver lining to these findings, since growers may be able to slightly adjust their kiln time. But even that is limited, as hops need to be dried within 12 hours of being picked. “Hop varieties mature at very specific periods of time,” Elliot said. “They might only be the perfect ripeness for two to three days, so there’s just not a lot of wiggle room.”

If the hop cones get overly ripe, she said they start to smell like onion and garlic — not qualities that brewers want in their beer. “[Farms] might be able to pause here and there,” she said. “But that’s very dependent on every farm and what variety they’re looking at.”

There have also been discussions about adding filters to the kilning rooms, said Coleman, but it ultimately comes down to the ROI since the kilns would require a pretty massive filter — about 32 square feet on each side of the opening, according to Shellhammer. The retail price for each panel is about $300 to $400, and large farms would need dozens if they wanted to outfit all their kilns

His team actually ran trials using filters at Elk Mountain Farm, and while they haven’t analyzed all of the data, he said it didn’t impact drying time. This may be a direction farmers move in, especially since one rejected bale could easily be a $1,000 loss, and one lot can contain hundreds of bales, according to Elliot.

“But what’s it worth if you can save 100,000 pounds of hops from being possibly rejected by spending X amount on a filter?” Coleman said. “It’s a math problem.”

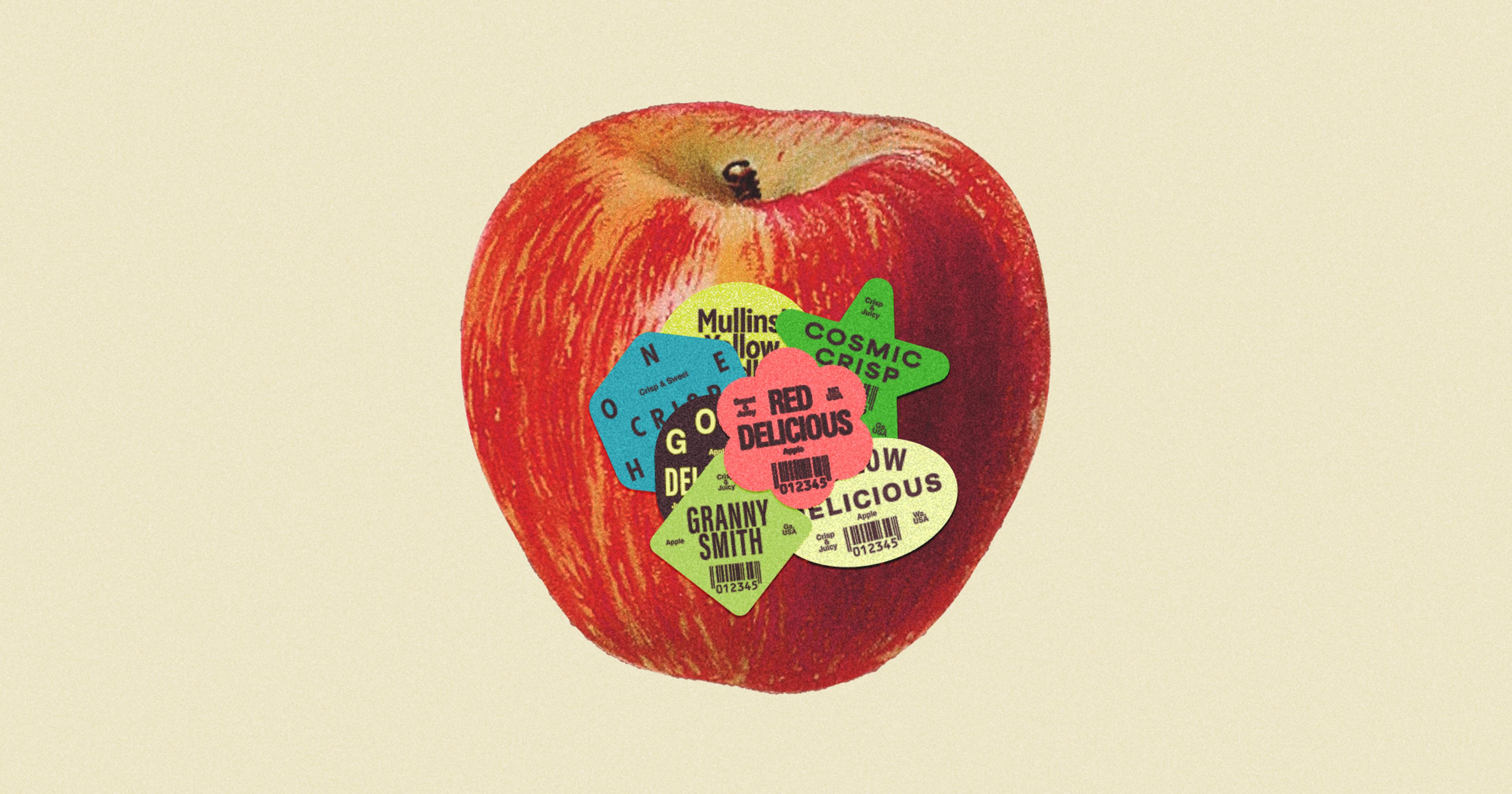

Shellhammer is also looking at whether certain varieties may be more susceptible to smoke than others, depending on the shape and properties of the different hop cones. It’s an area he’s continuing to research, as he tests mosaic hops samples that were collected from Westwood Farms over the summer.

The final piece of Shellhammer’s research is how smoke-tainted hops affect beer. This is particularly thorny because the hop cones and pellets might smell fine, but when they’re used to make beer, they could start releasing smoky aromas. Shellhammer compares this to wine grapes, which attach sugar molecules to the smoke particles, essentially neutralizing the smoky compounds.

But when the grapes are fermented, the yeast eats the sugar and the smoke molecule reappears. “So what you see with wine grapes is that the must doesn’t smell that smoky, but during fermentation, you start getting this evolution, and particularly during aging, this intense smokiness comes out,” Shellhammer said.

Shellhammer said there’s some preliminary evidence that the same thing happens with hops, and he’s heard from brewers that smoky flavors may continue to develop even after the beer is on the market.

And hops affect the beer differently depending on when they’re used. Shellhammer said those that are added during the pre-fermentation process tend to transfer less smoke, both because there are fewer hops and because the high heat might strip out the smoky compounds.

But the latter stage, known as dry hopping, uses far more hops to give beers their unique aromas and flavor profiles. “When you have low inclusion rates, it’s fine,” he said. “But as you have higher inclusion rates, you start to see that aroma signature come through in the finished beer.”

Shellhammer is doing brewing trials onsite at OSU, testing with different amounts of smoky hops. He plans to start releasing some of his findings in the coming months. Ultimately, he hopes to offer more definitive recommendations when it comes to adding hops in the brewing process; for instance, X amount of smoky hops are OK to use at Y stage.

He’s also hoping to be able to give growers some guidance tied to the Air Quality Index; for instance, if the AQI is above 150, farmers should avoid picking and drying hops (if they’re able).

Elliot said any findings that help give growers a bit more control would be welcome.

“The industry has taken a lot of progressive steps to try to understand how to grapple with the problem,” she said. “But at the end of the day, it still feels like it’s a problem that’s out of our control, because it’s really just [the result] of the environmental consequences.”