Long dismissed for its bitterness, the hickory nut is attracting attention for its oil — and its potential to elevate perennial agriculture.

Twenty-some years later, Sam Thayer can still feel the intoxicating rush of discovery when he realized what he’d found.

Growing up among the boreal forests of northern Wisconsin, Thayer developed a fondness for edible wild plants, yearning to live off the land in a way long since forgotten in most corners of our globalized food system. The perennial plants he prized — fruit and nut trees, forest botanicals, wild herbs, and alliums — offered a vision of something more sustainable, an agriculture that could build soil health and biodiversity rather than deplete it. But for all the bounty to be found in America’s native forests, there was no oil that could supplant the millions of acres of annual crops or billions of dollars of imports Americans rely on for staple fats. There was nothing to bind together a complete answer to the question he says drove him: “How can we feed ourselves without destroying the world we live in?”

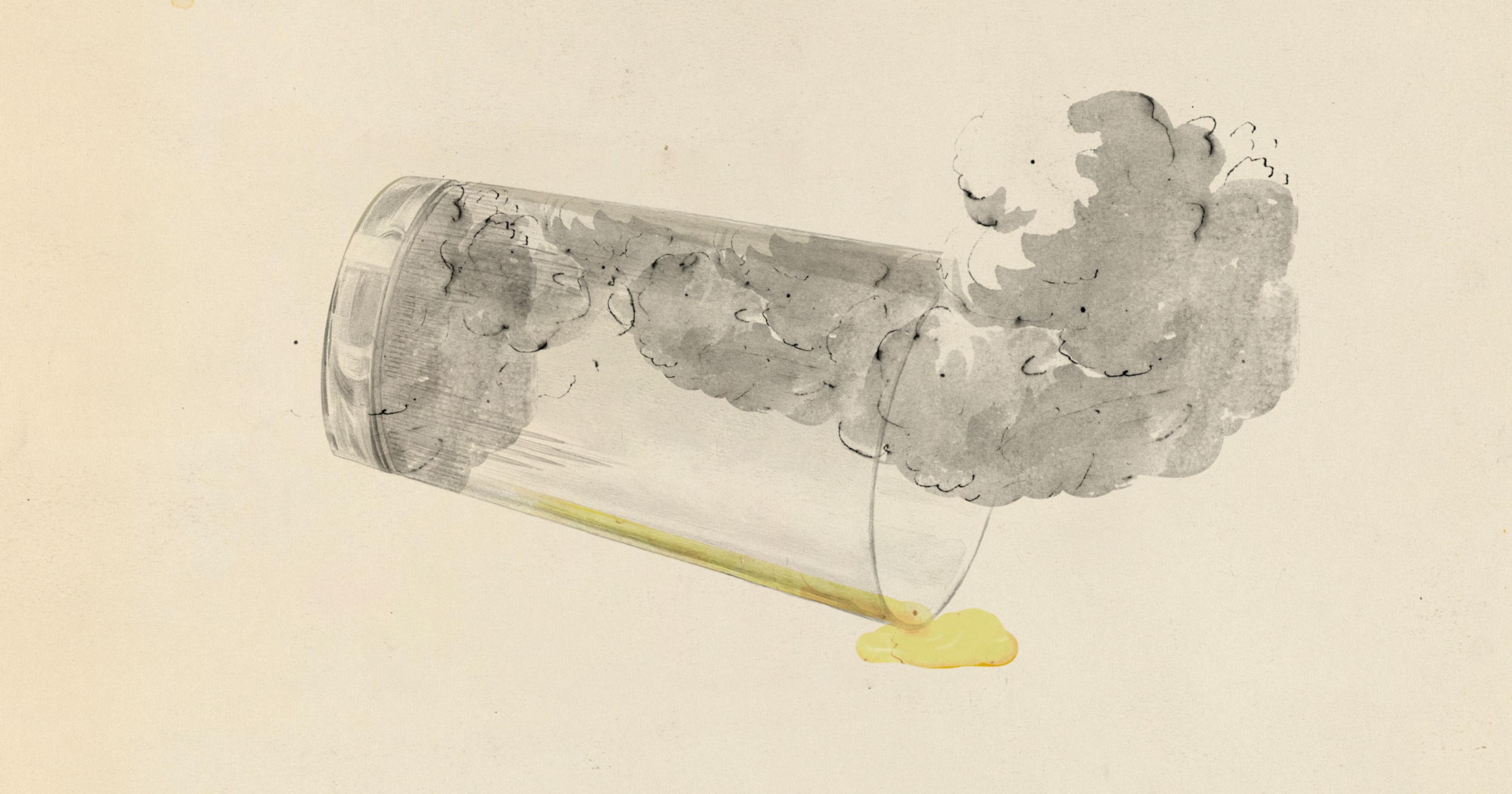

Then, while researching olive processing in the early 2000s, Thayer learned that tannins — the bitter compound in wine, tea, and the hickory nuts he’d been gathering since he was young — are not fat-soluble. Nuts from the bitternut hickory have long been disregarded as a food source because of their potent astringency. Even the USDA claims they have “little value for human consumption because of their high tannin content and extreme bitterness.” But what Thayer read had unlocked something. If tannins weren’t absorbed into fat molecules, then pressing hickory nuts would allow him to purge their bitterness and extract an oil with immense potential.

The first time he tried, the only tool at his disposal was a modified meat grinder. He ruined the machine in service of three ounces of oil, he says, but it was worth it. “This is magical,” he recalls thinking. “I didn’t even know oil could taste this good.” He later dabbled with a handcrank press and jerry-rigged another with a car jack before eventually biting the bullet and investing in a proper oil press.

The hickory oil Thayer produced was mild and buttery. As an author and educator on edible wild plants, he immediately saw its culinary value. Just as important, it was abundant. Because the tree’s native range covers nearly half the country, stretching from Texas to Minnesota and Florida to Maine, all that oil was out there just waiting to be processed.

Because the tree’s native range covers nearly half the country, stretching from Texas to Minnesota and Florida to Maine, all that oil was out there just waiting to be processed.

The realization changed Thayer’s life, transforming him into a hickory oil evangelist. Someday, he hopes, it might change the food system by opening the door to a perennial source of healthy oil. With climate change threatening the olive oil industry and seed oils situated squarely in the crosshairs of the MAHA movement, he just might be onto something.

“Here we have the North American equivalent of the olive,” Thayer says. “And it’s being totally ignored.”

Through reviewing archaeological literature and speaking with Indigenous communities, Thayer learned that hickory oil was once part of Native foodways disrupted by colonization. But he has encountered no evidence of its production in North America over the past two centuries, until he began pressing his own. “It’s essentially a well-documented but dead food tradition,” Thayer says. Since his discovery, he’s become the de facto leader of a small group of tree crop enthusiasts who share his vision for a hickory oil renaissance.

“If we’re interested in sustainable agriculture, not just a buzzword but something that’s really long-term sustainable, this is the ultimate thing America has,” Thayer says.

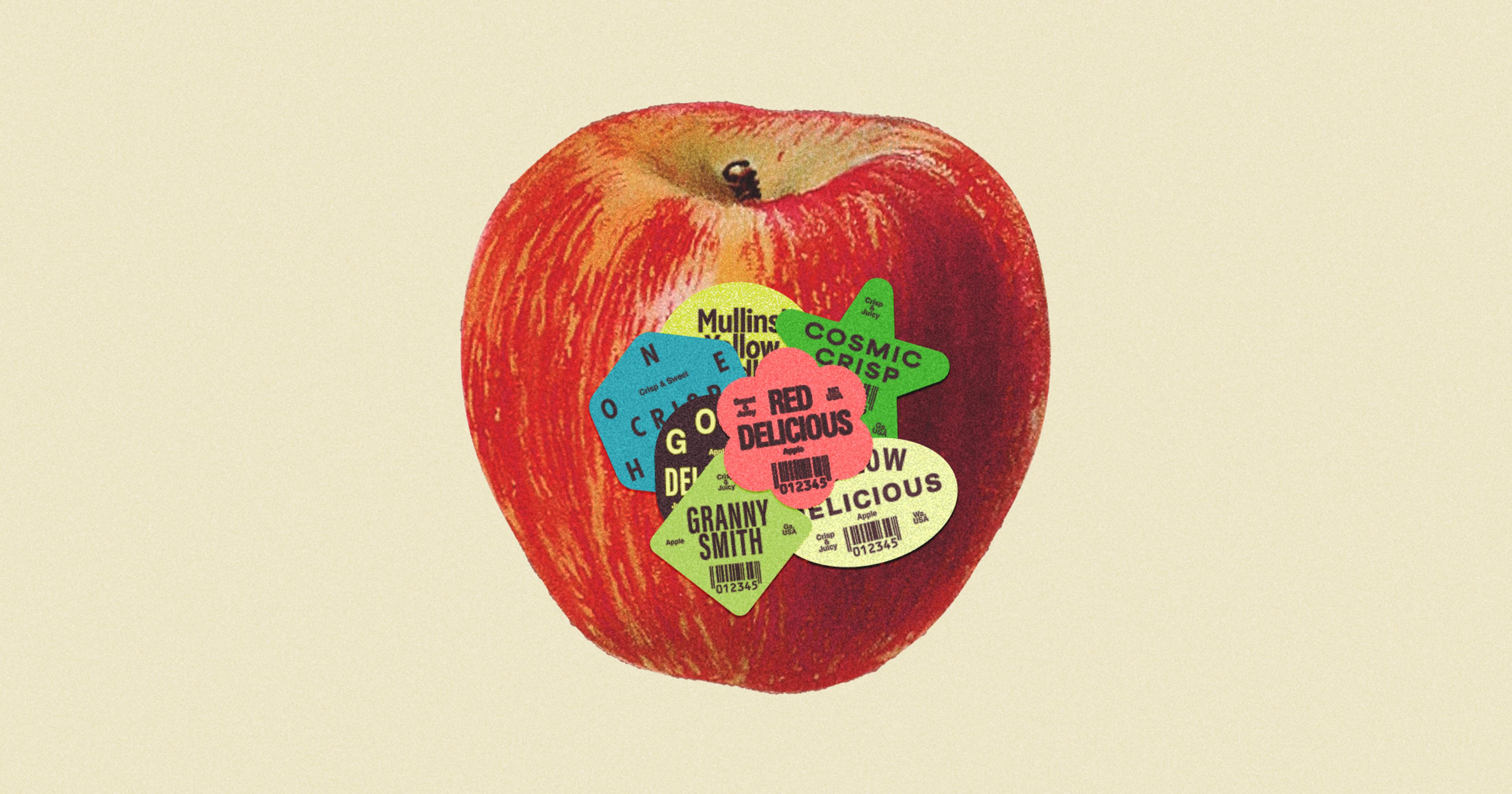

The bitternut hickory — increasingly called yellowbud hickory to shed any negative connotations — is among the most widespread hickories in North America. A cousin to the pecan, its nuts have a fat content around 75 percent and thin husks that maximize yield and minimize processing. According to Thayer and other producers, early indications suggest yellowbud’s per-acre yield could be on par with that of canola or sunflower — annual oil crops with a combined value of roughly $1.5 billion, per USDA data.

Hickory oil’s high smoke point — around 450 degrees — gives it a leg up on more delicate alternatives like olive oil that burn easily in the frying pan. And its distribution of fatty acids purportedly rivals the healthy balance that has inspired American consumers to triple their olive oil intake in the past 30 years. The tree, meanwhile, can tolerate both drought and flood; combined with its enormous range, it’s known to thrive just about anywhere.

None of that would matter if hickory oil didn’t taste good. The raw, cold-pressed oil is smooth and neutral, making it an asset for everyday cooking. When roasted before pressing, it becomes an attractive finishing oil, rich and nutty with the aroma of a pecan and a flavor profile bound to get a chef’s wheels turning.

“Here we have the North American equivalent of the olive, and it’s being totally ignored.”

“I had one woman who tried some oil and told me, ‘That is to die for,’” says Zach Elfers, co-founder of Pennsylvania’s Keystone Tree Crops Cooperative, which bottled and sold its first four-gallon run of hickory oil last winter. Elfers expects to produce 60 gallons or more this season. “I really think it’s one of these products that sells itself. You barely need to market it. You just need to get people to taste it and your work is done.”

The real work, though, happens before the oil is ready for consumption. For now, anyone pressing hickory oil — a group whose current members have all learned by Thayer’s side — begins by gathering fallen nuts from hickories that took root long ago. The oil now being produced comes exclusively from wild nuts and will continue that way until growers take an interest in the product and begin planting trees with oil in mind. The very beginnings of a cultivated crop are slowly starting to take shape. The first yellowbud orchards are just now being put in the ground, including by the Hudson Valley Farm Hub, a regenerative agriculture nonprofit in New York that has planted 1,200 seedlings in the past two years and has plans for another 800 this year.

The Farm Hub’s trees are sourced from Yellowbud Farm, a Massachusetts nursery and research farm that chose its namesake as “a metaphor for seeing the unseen abundance of our landscape,” Yellowbud founder Jesse Marksohn says. A friend of Marksohn’s often reminds him what the food system could gain by harnessing the hickory’s potential: “It’s like we’re in Italy and we don’t know that olives can become oil.”

Among the tight circle of hickory oil advocates, nobody is producing more than Fancy Twig Farm’s Levi Geyer, who made 75 gallons last winter. A twenty-something Iowa farm kid, Geyer is committed to developing a more permanent form of agriculture in the land of corn and soy. He’s long heard his neighbors say, “We have to feed the world.” But as a concerned environmentalist, he believes it has to be done without the soil degradation created by annual systems. Through that lens, hickory oil offers a potent alternative, Geyer says. Unlike canola that must be replanted year after year, a yellowbud tree can live to 200, producing more nuts as it ages. With the help of a Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education grant, Geyer is exploring how woodland management practices can improve both production and ecosystem health.

“Right now it’s a specialty product, but someday it has the potential to be the butter on people’s tables.”

Geyer picked up his first nuts a few winters ago and pressed enough for three quarts of oil. His yield has grown tenfold in each of the past two seasons. In online sales and at the Iowa City Farmer’s Market, his eight-ounce bottles go for $20.

“Right now it’s a specialty product,” Geyer acknowledges. He’s the lone producer in Iowa and one of just a handful nationally. “But someday it has the potential to be the butter on people’s tables.”

It already is for Geyer, who says he and his girlfriend go through about a quarter-cup a day. But while Thayer says there are enough wild yellowbud hickories to put oil on the shelves of every grocery store in the country, it’s a long journey from forgotten foodway to pantry staple. Several producers, including Thayer and Marksohn, are in the initial stages of breeding and selecting for the next generations of yellowbud that could populate orchards if growers are inspired to join the fray. As Geyer admits, “The people doing it now are a little bit crazy and passionate and idealistic.” He suspects more pragmatic individuals will perk up when they recognize the opportunity.

In the meantime, the emerging hickory oil market can act as a bridge between wild and cultivated ecosystems, Elfers says. Only a minuscule number of yellowbud hickories have been planted for oil production, but wild-harvest production is growing because Thayer’s enthusiasm is catching on. Like olive oil in the Mediterranean, “it tells a really beautiful story about our bioregion and what we have to offer,” Elfers says. And given the promise of hickory oil — the taste, the yield, the nutritional composition — “it just seems like a no-brainer that this should be a fixture of our economy,” he adds.

Considering the USDA’s dismissiveness of the hickory nut, it’s not surprising that its oil has received scant attention from the types of institutions that could explore and realize its potential. Brandon Miller, assistant professor in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Horticultural Science, is hoping to change that.

“It’s not just a handful of us nut tree fanatics who think this is the next big thing.”

Like others, Miller says he was convinced by his first taste that hickory oil deserved his attention. He plans to study its chemical composition to develop a better understanding of its health benefits — derived from its balance of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids — and how it compares with readily available alternatives. He’ll also conduct taste panels with consumers to get a window into the oil’s public perception. The goal is to show that “there really is something to this,” he says. “It’s not just a handful of us nut tree fanatics who think this is the next big thing.”

Miller grew up in the Chicago suburbs, playing among the stately hickories that populated his grandparents’ property. If he appreciated the yellowbud’s natural beauty at a young age, it’s now the tree’s resiliency and lifespan that he admires as a horticulturalist. The yellowbud has all the indicators of reliability that a grower would seek from a long-term investment, he says. It also has something to say about reorienting the food system toward what’s readily available in local landscapes.

“The opportunity to have something that’s right in our own backyards that has been largely neglected is exciting,” Miller says.

If a hickory oil market develops in the way its fondest supporters desire, Thayer’s early experimentation will prove to be a catalyst. It certainly was for him. In the spring of 2016, following the birth of his youngest daughter, he planted a pair of yellowbud seedlings in her honor, drawn from the woods surrounding his home. One began producing nuts in 2023, the other in 2024. Even in its infancy, the first tree yielded almost four gallons of nuts last winter, he says, enough for a precious quart of oil.

“I never thought of it as symbolic, but it did occur to me later that these might have been the first yellowbuds planted for growing oil,” he says. “At least in recent history.”