People aren’t eating apples like they used to, but flashy new cultivars may not be the solution.

Apple people are a spirited sort, able to talk fervently about the aging qualities of an Albemarle Pippin, the rock hard crunch of an Arkansas Black, the complexity of an Esopus Spitzenburg, the sweet-yet-acidic bite of a Mullins‘ Yellow Seedling. They’ll take road trips through Maine to seek out rare apple varieties; they’ll dedicate their labor to documenting and preserving wild seedlings. Apple people make films that rival Wes Anderson. They drive seven hours, one way, from their home in Denver to the very southwest corner of Colorado just to pick up a Pewaukee apple tree. (Okay, that last one was me.)

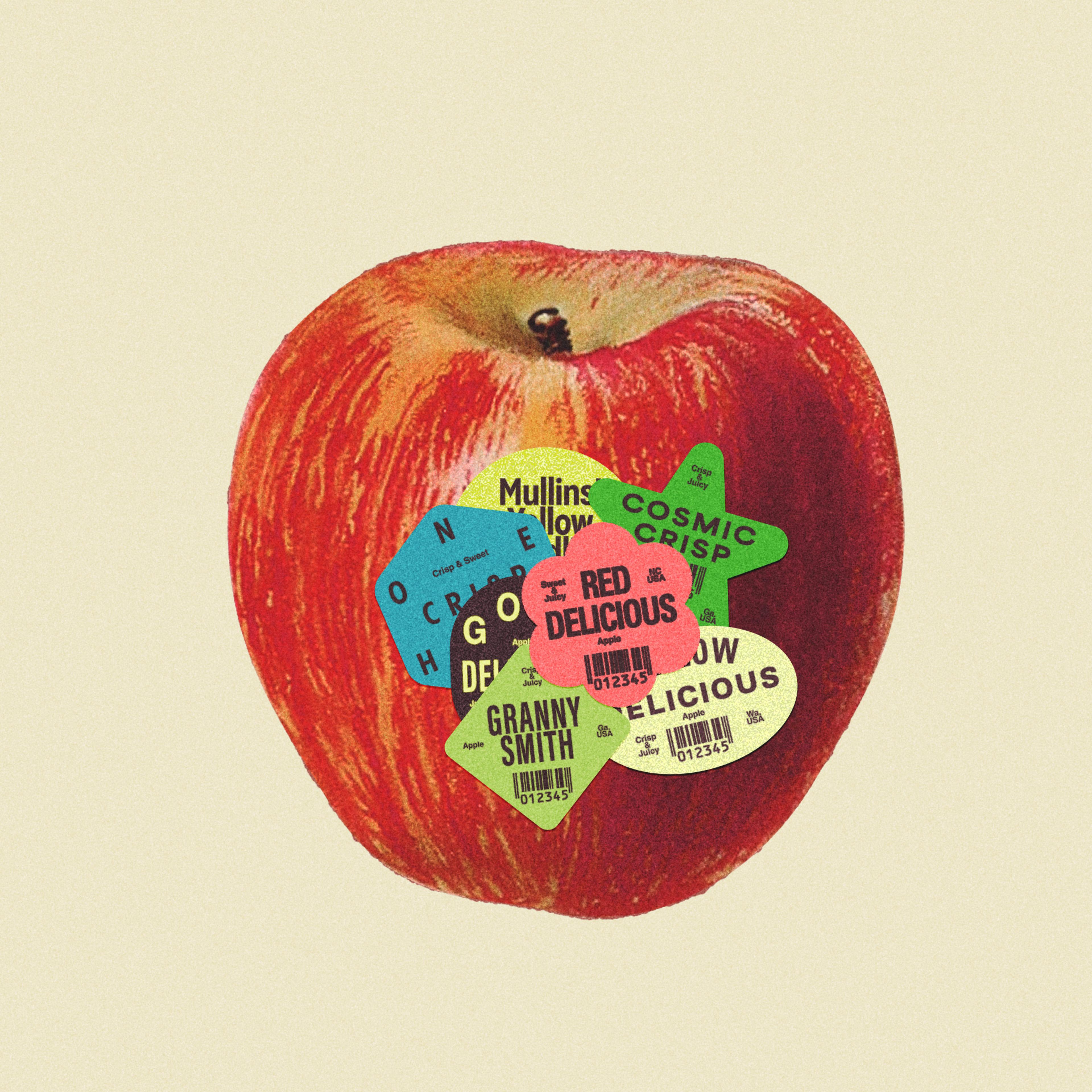

Beloved though they may be, fresh apple consumption has trended down by about 2.2 pounds per person since the 1990s, despite popular newer varieties like Honeycrisp and Cosmic Crisp. “Something’s gone wrong where we haven’t been able to increase the per capita consumption despite how good ... many of the most recently developed varieties are,” said Luke Tonnemaker, a fourth generation farmer near Royal City, Washington.

As orchards consolidate, increase yields per acre, and vertically integrate, entire regions have become very efficient at growing apples. But the domestic and export market for the fruit continues to diminish. Cosmetically imperfect apples remain unpicked on trees, and the cost to grow apples — from inputs all the way to labor — keeps increasing.

“I feel like we’ve lost the plot a little bit and that’s one of the reasons that we’re seeing apple consumption, both fresh and processed, go down,” said Ben Wenk, a seventh generation apple grower in Adams County, Pennsylvania. “The whole experience has been so consolidated and so driven by capitalism, and in some ways it’s very shortsighted.”

–

Tonnemaker grew up eating Honeycrisp grown on his family’s 126-acre farm. The beloved apple, developed in the 1980s by the University of Minnesota’s apple breeding program and released to apple growers in 1991, changed consumer expectations of what an apple can be. “For better or worse there’s been such a big push to develop new apple varieties since Honeycrisp raised the bar on the apple eating experience,” he said.

Even though people still like the cultivar, “It feels like everyone’s looking for the next Honeycrisp,” said Wenk. New varieties flooding the market, often crossbred with Honeycrisp, are in effect different versions of the same thing: juicy, flavorful, sweet with enough acidity to be considered tangy.

Since Honeycrisp are notoriously tricky to grow, many producers would love an alternative that can, in theory, fetch a premium price. (“In theory” because from August 2023 to July 2024, the price that a grower could fetch for a 40-pound box of Honeycrisp dropped from $67.85 to $30.55.)

“It’s hard to understand how the least valuable component of a bottle of apple juice is the apples.”

But consumers? “I don’t really know which of these new varieties that are trying to reinvent the wheel — or you know, put the toothpaste back in the tube, however you want to talk about it — I’m not sure which of those has a realistic chance of having that effect,” said Wenk.

It is in this spirit that I bring up Cosmic Crisp, launched in 2019 and patented and trademarked to be grown exclusively in Washington. I’m not here to malign the apple nor the Washington State University breeding program that produced it.

But here’s my bias: Although I grew up 80 miles east of Wenatchee, the apple-growing center of Washington, the nation’s top-producing state (valued this year at approximately $2.3 billion), I grew up on Red Delicious, which Washington can grow very well. The quintessential apple was once sweet with the taste of muskmelon — it forever changed the apple industry.

But since I mostly ate flavorless and mealy mainstream Red Delicious, I did not truly appreciate or even like apples until I spent 10 years selling fruit for a small, south-central Pennsylvania farm at a farmers market. There I realized apples are like basically any other agricultural product — good enough from a grocery store but potentially transcendent when sourced from a farmer who values quality and flavor over quantity and appearance. “Apples to apples” becomes a useless idiom when removed from its standardized implication.

Cosmic Crisp apples, a cross of Honeycrisp and Enterprise, have their ardent fans; they also have their detractors. (“It’s a big nothing sandwich, as far as I’m concerned,” said Wenk.)

Washington may be good at growing them, but it’s a state that has flooded the market with apples in a marketplace “already rife with overproduction and price stagnation and typical economic hardship,” said Wenk. (And tariffs, which already impacted the apple industry in 2018, continue to be an issue.) According to the orchard- and vineyard-focused magazine Good Fruit Grower, this year in Washington, growers are harvesting an estimated 125 to 137 million boxes of apples. Per the USApple Industry Outlook 2025, Cosmic Crisp increased in production by a whopping 798 percent compared to the 2020/21 season.

“If you knew how little apples were selling for ... you would wonder why you’re paying $2 or $3 a pound.”

An abundance of apples hasn’t led to cheaper prices for consumers, and it hasn’t meant more profits for farmers. (Even though there’s plenty of product, the inputs to produce them are more costly and grocery stores can set prices however they please.) “If you knew how little apples were selling for, how much the growers were getting from the system that is ending up in grocery stores, you would wonder why you’re paying $2 or $3 a pound,” said Tonnemaker.

(Putting aside waste and potential solutions, even selling fruit to a processor isn’t a viable option for farmers when offers are shockingly low, like the two cents per pound that Tonnemaker was quoted within the last few years. “They put it at that price to discourage you from bringing it in because they don’t even want it,” he said. “It’s hard to understand how the least valuable component of a bottle of apple juice is the apples.”)

Meanwhile in the grocery store, we haven’t progressed too much beyond the homogeny of Red Delicious, Yellow Delicious, and Granny Smith. “That’s a weakness of the supermarket model,” said Tonnemaker. Big stores count on brand or variety recognition since they don’t have staff to talk to customers about every single apple, to explain each variety and which ones are best for pie and baked goods, which ones improve with age, which ones make a velvety sauce. “Apples are so diverse and can be used in so many different ways,” said Wenk, “and then grocery store produce aisles are restricting the diversity of the apple down to six or seven varieties.”

“I think a lot of us are looking to these true heirloom varieties and trying to educate people that of course you can make a pie with a Gala, but there’s all these apples that are specific for baking that just make it that much better,” he added.

–

Apples used to be regional and use-specific. Now they’re everywhere, all the time, seasonality be damned. For those who want to go out of their way to find unique apple varieties, there’s much to discover, said Wenk. “It feels like this kind of niche, underground apple counterculture, those of us who are real nerds about it.”

So are the worlds of heirloom apples and big time plant breeding in tension, or are they different slices of the same pie?

“I don’t think that new apple breeding and old apple discovery have to be opposed to each other at all,” said Jude Schuenemeyer. He and his wife Addie run the Montezuma Orchard Restoration Project near Cortez, Colorado, the source of my Pewaukee tree. “Cultivars are cultivars because somebody found a seedling and decided to take a cutting and graft it,” he added. Human interaction with trees prevents certain cultivars from going extinct; plant breeders creating new apples are part of that process.

“It feels like this kind of niche, underground apple counterculture, those of us who are real nerds about it.”

Tonnemaker sees Cosmic Crisp as having the potential to save the small and midsize apple orchard in Washington. “If Cosmic can help provide an apple that gives people a consistently good eating experience in the store like it should, maybe we can get that apple consumption number back up,” he said. “And if it’s economical to grow, which I think it is in comparison to other varieties, you can get a better price back to growers.”

Schuenemeyer also points to downstream effects from the cider industry: “The reason why any cider has grocery store or liquor store shelf space is because of Angry Orchard.” Sometimes you need a mass-produced product to get your foot in the door. And while fresh consumption of apples is down, “It’s better to have people that decide that they like apples,” said Schuenemeyer. “The next step, though, is how do you introduce them to the other ones?”

Apple varieties already exist that excel at varying applications, whether it’s fresh eating, baking, drying, saucing, juicing, or fermenting into cider. “All those apples are being largely overlooked in a quest for some new sameness,” said Wenk. “The ‘same thing but new’ seems to be trumping ‘it’s different but old.’”

It’s true for so many things beyond produce, but perfectly good — great, even — varieties of apples lose their luster once they become too popular. Take the Mullins’ Yellow Seedling, discovered accidentally in 1891 in Clay County, West Virginia. Sweet like honey, with a little spice and acid for balance, the yellow apple is juicy, crunchy, and excellent for fresh eating and turning into sauce or butter. It grows well all over the country, bears plenty of fruit, and produces ample pollen to pollinate other varieties.

“Consumers love stories, right? With these older cultivars, you open up a whole world that most of them never knew existed.”

You’ve probably even tasted this apple. In 1914, horticultural company Stark Bro’s introduced it as Golden Delicious. If it were discovered yesterday, it’d be a runaway success, said Wenk, but “it’s not weird enough to be an heirloom and it’s so ubiquitous that it gets lost in the shuffle.” I tried a Colorado-grown Golden Delicious this season and was blown away by its burst of juice and complex flavor.

While new apple varieties can benefit growers in certain regions, the old ones still have potential. “If you can’t access the same new and zippy product that everybody else has, or that the big boys have, how do you keep that farmland viable farmland?” asked Schuenemeyer.

For some growers to have a future, it won’t be on new patented and trademarked varieties, especially in locations like Colorado, which once boasted a vibrant apple economy, but where growers might not be able to afford access to managed varieties. “But we can access the old cultivars that were proven to grow well here for a long, long time,” said Schuenemeyer. “Consumers love stories, right? With these older cultivars, you open up a whole world that most of them never knew existed.”

And as farmland gets more expensive, less attainable and consolidated by corporations and private equity, styles of farming that work on small acreage present an opportunity. “We really feel like orchards can be successful on an acre or three acres or 10 acres, that they can be viable commercial enterprises,” said Schuenemeyer. “That’s really what we’re looking at, is the ability of people to keep agricultural land. We are so removed from farmers to consumers that I think most people no longer understand the value of farmland until that barn in the field is now the barn surrounded by houses, and the field or the orchard is no longer there.”