The U-pick business model, which relies on farm visitors to do the harvesting, has the potential to produce big profits. But its success depends on an array of uncontrollable variables.

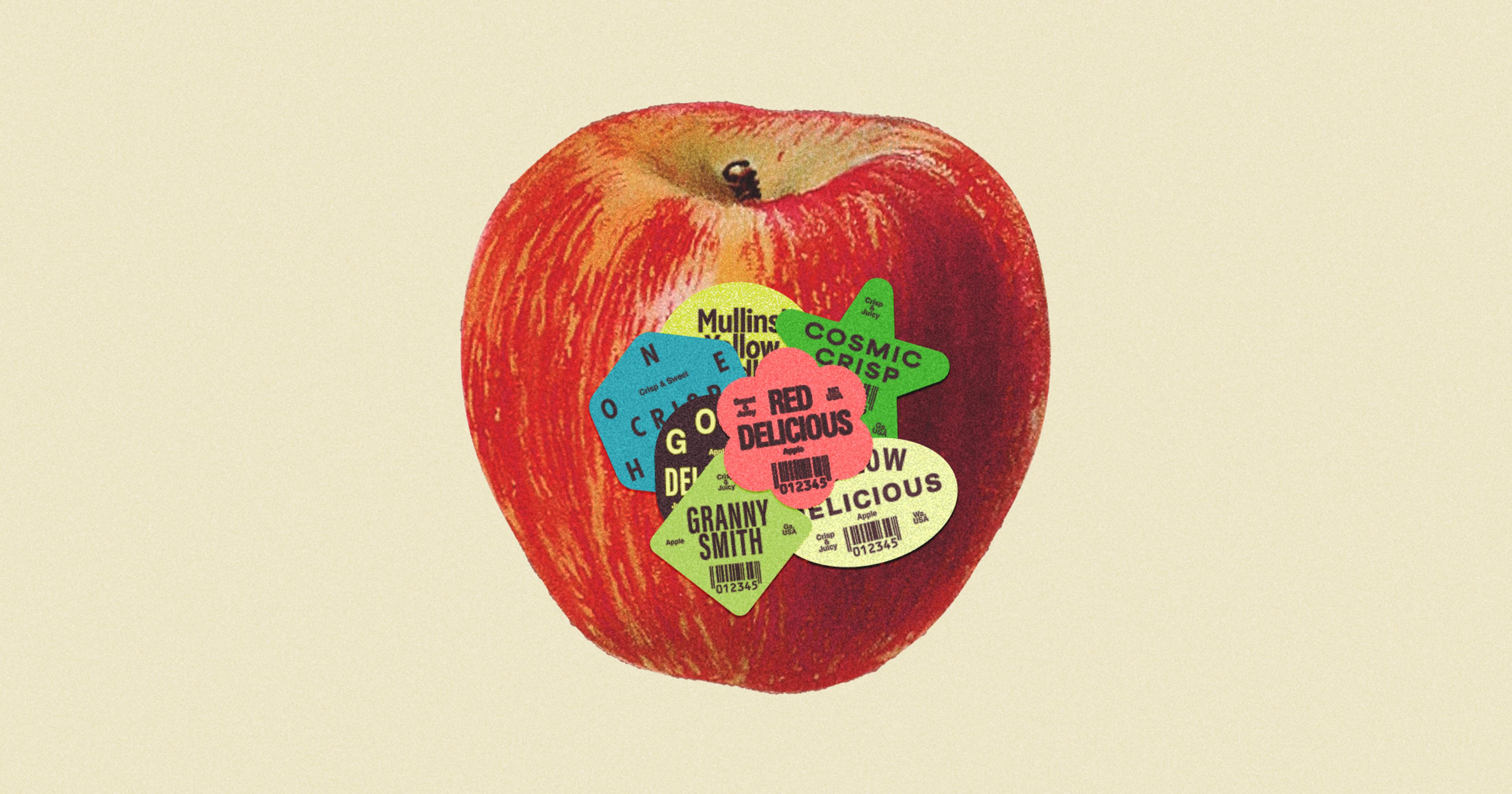

Every summer, people flock to farms to pick their own fresh cherries, berries, peaches, and plums. When autumn rolls around, they head to orchards for apple picking and pumpkin patches in search of the perfect porch gourd and, of course, capturing plenty of Instagrammable content along the way.

Pick-your-own (also called U-pick) farms might be widespread and ubiquitous now, but that hasn’t always been the case. The concept first emerged during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when prices for fruit and vegetable crops reached historically low levels as war-torn countries began to recover and no longer relied on U.S. exports. For many growers, it was cheaper to leave their crops in the field to rot than it was to harvest them and sell them for a pittance. That’s when a ragtag bunch of cherry growers in Wisconsin decided to offer their fruit directly to the public for pennies a pound. The only catch was they’d have to come out to the farm to pick the cherries themselves. And so the bustling pick-your-own industry was born.

Today, U-pick programs often make up just one part of a farm’s operations, a far cry from their original role as a sort of Hail Mary — and they’re certainly more lucrative than they were in the 1930s. Pick-your-own operations now exist in every state, luring urbanites and families out to the country to spend a wholesome weekend. Advancements to automobiles and road infrastructure have helped pave the path, too.

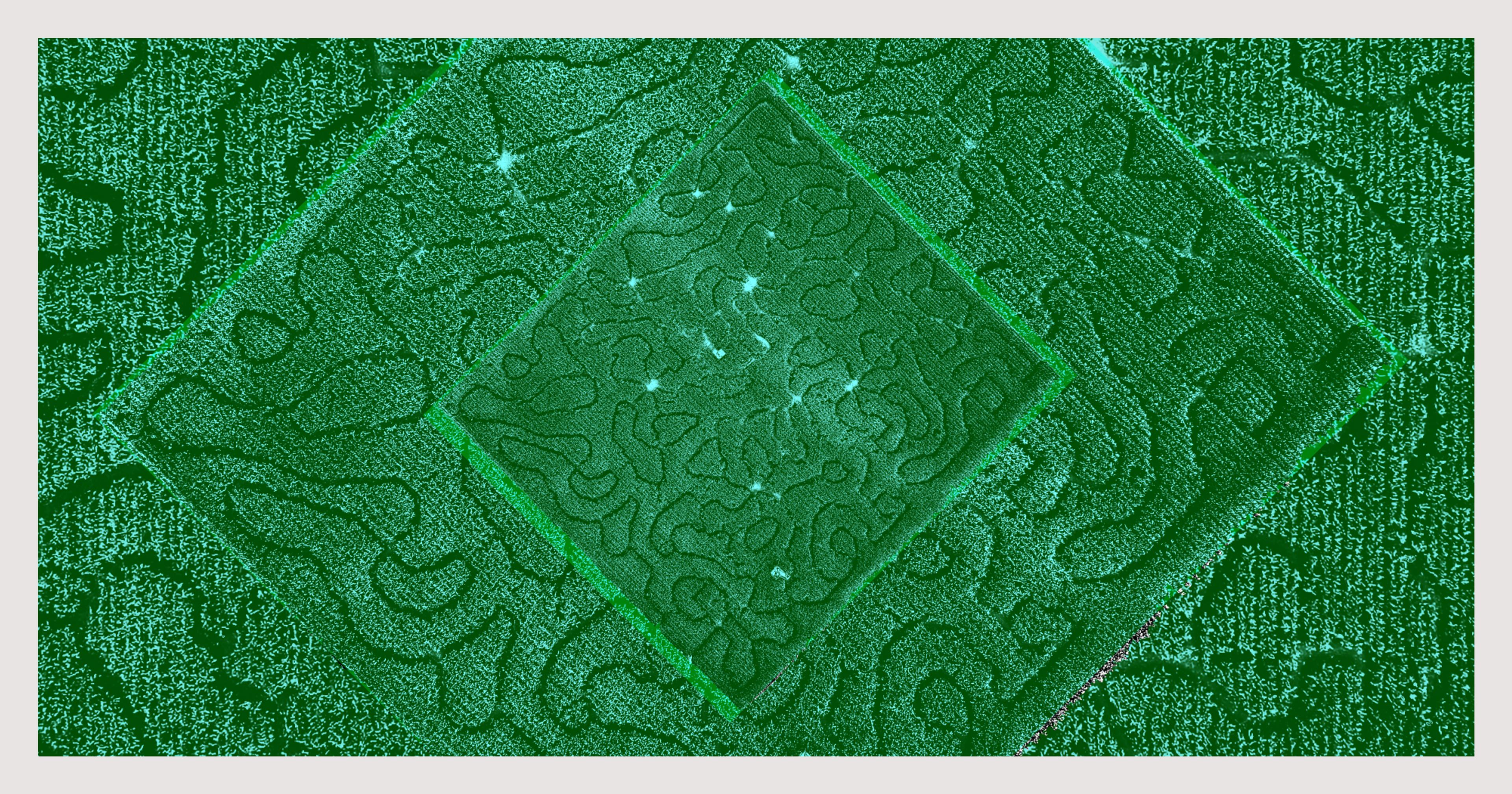

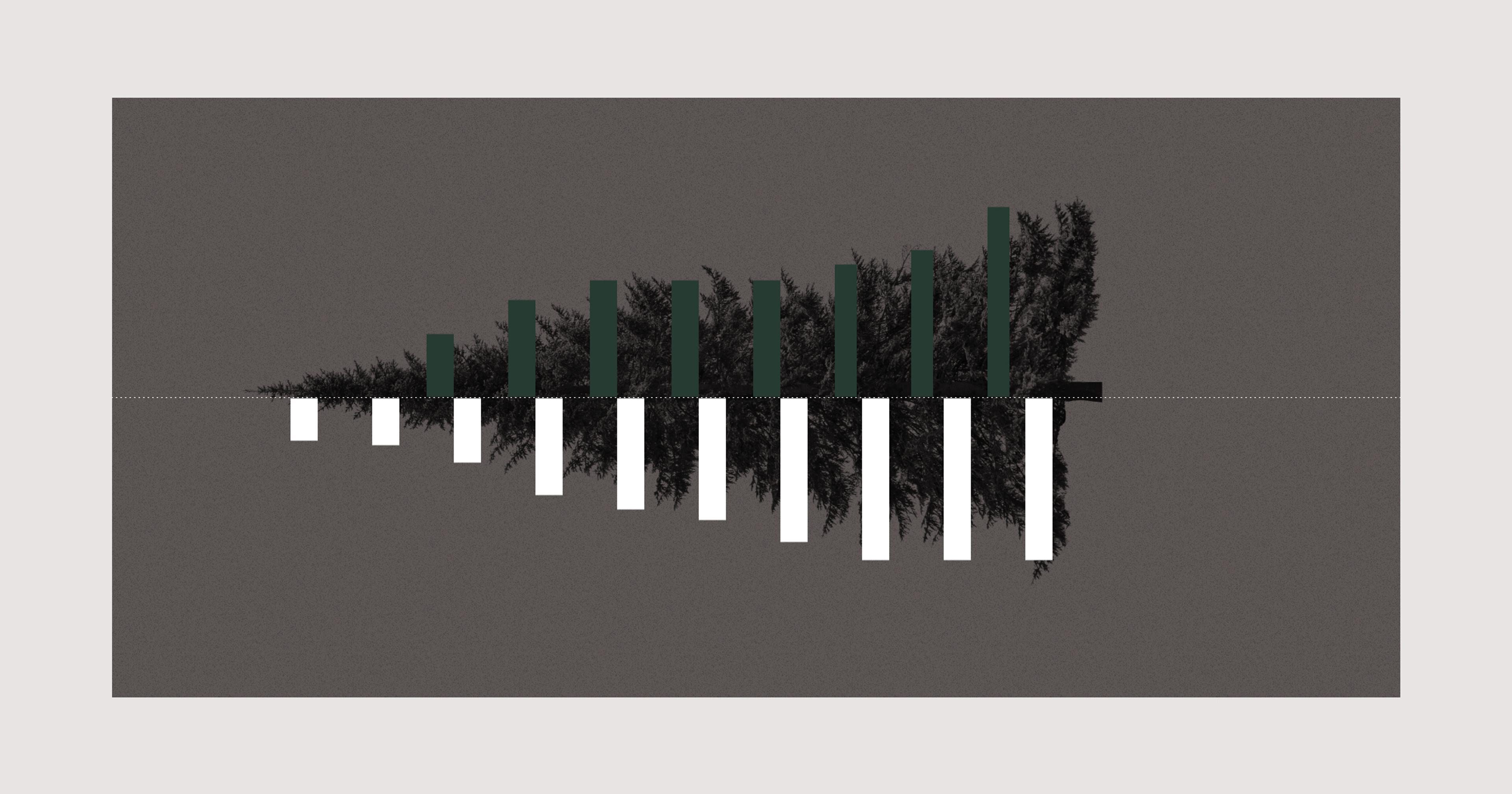

Agritourism has boomed over the last two decades, with revenue more than tripling from 2002 to 2017. According to the USDA, agritourism revenue grew from $704 million in 2012 to $950 million in 2017. Pick-your-own farms have played a key role in that growth, attracting customers to farms to pick or cut their own fruits, vegetables, flowers, or Christmas trees out of fields — and charging them to do so.

The U-pick business model reduces a farm’s reliance on labor for harvesting, and eliminates the need for working with distributors, giving farms immediate access to the profits. “Getting the fruit out of the field is great. You’re getting cash flow coming onto the farm earlier, so that’s helpful,” said Anu Rangarajan, director of the Cornell Small Farm Program, and former owner of a pick-your-own strawberry farm in Freeville, New York.

As with every corner of agriculture, however, running a U-pick operation comes with its own unique risks. “There are lots of pros and cons of U-pick,” said Megan Bruch Leffew, a value-added agriculture marketing specialist for the Center for Profitable Agriculture at the University of Tennessee. “Bringing the customer to your farm and them doing the labor of picking can be a savings to [farmers] so they don’t have to pick all of it and transport it to market. On the flipside of that, consumers don’t often know how to appropriately pick and can damage plants, so there’s a loss aspect that needs to be built in when folks are pricing product.”

“When you bring people out to the farm, you need some added risk management and insurance.”

While plenty of consumers embrace the opportunity to pick their own fruit, and are happy to pay to do so, others have critiqued the idea of being charged to do labor. But as Leffew points out, there are hidden costs associated with U-pick fruit and vegetables that more commercial operations don’t have to factor into costs. “When you bring people out to the farm, you need some added risk management and insurance,” she said. “So there’s costs associated with that, as well as the costs of providing customer comfort. People are going to need access to a restroom, handwashing, and other things.”

And then there’s the unpredictability of weather, a factor that farmers of all kinds deal with, but one that has the potential to wipe out an entire crop for a U-pick farm, causing a trickle-down effect on the farm’s overall profits. “Pick-your-own farms oftentimes have an on-farm retail market where you can buy pre-picked fruit and value-added products like fruits, jams, and salsas,” said Leffew. But if there’s no pickable produce, or even if the weather is just unpleasant, agritourists might not trek out to the farm at all, delivering a one-two punch to the farm’s sales.

This year, fruit growers across the country have experienced significant crop loss after erratic weather. Georgia lost more than 90% of its peach crop this year due to an abnormally warm winter. Powerful rainstorms in California flooded hundreds of acres of strawberry fields. And in the Northeast, orchards and vineyards suffered damage from a late May frost that wiped out the large majority of this year’s crops.

At Rose Hill Farm in Red Hook, New York, co-owner Holly Brittain estimates the frost wiped out 95% of this year’s cherry crop. A portion of the fruit grown on the farm — which includes apples, strawberries, blueberries, peaches, cherries, plums, apricots, nectarines, grapes, and more — goes to the U-pick side of their business. But more importantly, the fruit is needed to fuel their lucrative cider and winemaking operations. That’s led the farm to not be able to offer pick-your-own strawberries or cherries to the public this year, which means those would-be visitors might not make it out to the farm, where they’re likely to spend additional money in the tasting room.

“Our culture is starving for connections to nature. This is one more way that people can feel connected.”

“We couldn’t open those for pick-your-own, which is pretty devastating because cherries as a unit cost do pretty well, and that’s our first fruit of the season. Folks are excited to come back [for cherries], and people drive from as far as Long Island and New Jersey. So that was a big ouch for the beginning of the season,” said Brittain, who acknowledges these unexpected and hard decisions come with the territory of running an agritourism business.

A lack of early-season fruits hasn’t seemed to dull interest in the farm’s other pick-your-own offerings — which will help support the farm as it awaits support from federal disaster assistance programs to help offset costs incurred from a devastating late-season frost. Rose Hill recently opened its blueberry fields to U-pick, and the seasonal flow of tourists has resumed.

However, the power of a pick-your-own business extends beyond their ability to lure customers onto a farm. “Our culture is starving for connections to nature. It’s one more way that people can feel connected — connected to their food, connected to where they live,” said Rangarajan. “U-picks do a huge service for connecting people to our food system, and especially the seasonality of food … and [gives farmers] the opportunity to have important conversations with people who can support agriculture more actively.”