And how the 2008 financial crisis is still making it harder for you to find a tree.

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Southern Vermont cut-your-own Christmas tree farm Elysian Hills Farms was overrun with rosy-cheeked young children holding steaming mugs of apple cider. Parents hiked off into the woods to saw down their own little piece of holiday magic, before farm staff expertly wrestled each tree on top of their cars. It was a scene straight out of Norman Rockwell, or maybe a Lexus commercial.

“I always say it’s like bagging a vegetarian deer,” said Elysian Hills owner Jack Manix, who bought the farm with his wife eight years ago. “They cut the tree and they all stand around and take a selfie for their Christmas card, and the tree goes in the back of their truck.”

Manix is a 73-year-old New Englander with a mop of white hair whose primary business is a farm stand and garden center whose business he describes as “phenomenal.” In the warmer months, he runs a 35-acre organic vegetable farm which has been in his family since 1770 where he grows everything from artichokes and strawberries to Carolina Reaper peppers. Manix got into the Christmas tree business on a whim, when he and his wife were buying their own tree one snowy day and found their lives upended by an inconvenient attack of Christmas spirit. When asked about how that decision has been playing out, he laughed.

“Anybody will tell you a Christmas tree farm is not a huge money maker,” he said. “A huge, huge pleasure maker,” but not a particularly lucrative one.

Tough Business

Many farmers and industry experts agree that the Christmas tree farming business — you could melodramatically call it the lifeblood of our nation’s holiday cheer industrial complex — is labor-intensive, with thin margins, incredibly long lead times, and bonus opportunities to disappoint adorable children.

People in the Christmas tree business are not shy about telling you there is no money in the business. At the time Manix bought Elysian Hills, its owners had actually tried to transition it to three other couples, all of whom failed. When asked why, he laughed and said, “Maybe they found out how much work it is and how little the return is.”

The first thing to understand about Christmas trees is that they don’t grow particularly fast. A tree you find in the store is anywhere from five to 14 years old, depending on its size and variety, grown with seedlings purchased from suppliers. One of the main pressures a Christmas tree farm faces is not overselling in any individual season so that they have enough trees to sell next year. Easy in theory, but hard in practice when you’re standing in front of a field of Christmas trees and telling a family they can’t have one.

“People go, ‘We can go in there and cut! There are some good ones in there!’” Manix said. “I say it’s like cashing in a savings certificate early and paying a penalty. A lot of these could be cut, but next year they’ll be a foot taller and 20 bucks or more. It doesn’t really make sense to sell all the little ones.”

“And then you have to harvest the tree, and the expense isn’t just cents per tree, it may be a dollar or two per tree to get that tree out of the field and stored.”

The long growing period for trees also means many visits by farmers — labor costs which add up substantially over time. “A farmer or farmworker has visited, walked past that tree, drove past a fir or to spray for weeds or to mow or whatever over 150 times,” by the time it’s harvested, said Jill Sidebottom, a seasonal spokesperson for industry trade body the National Christmas Tree Association (NCTA) and an integrated pest management specialist at North Carolina State University.

“And then you have to harvest the tree, and the expense isn’t just cents per tree, it may be a dollar or two per tree to get that tree out of the field and stored where it’s not going to dry out. And of course you need to do that no matter what the weather is. It’s just kind of a herculean effort.” The vast majority of Christmas tree farmers need a supplemental off-farm income.

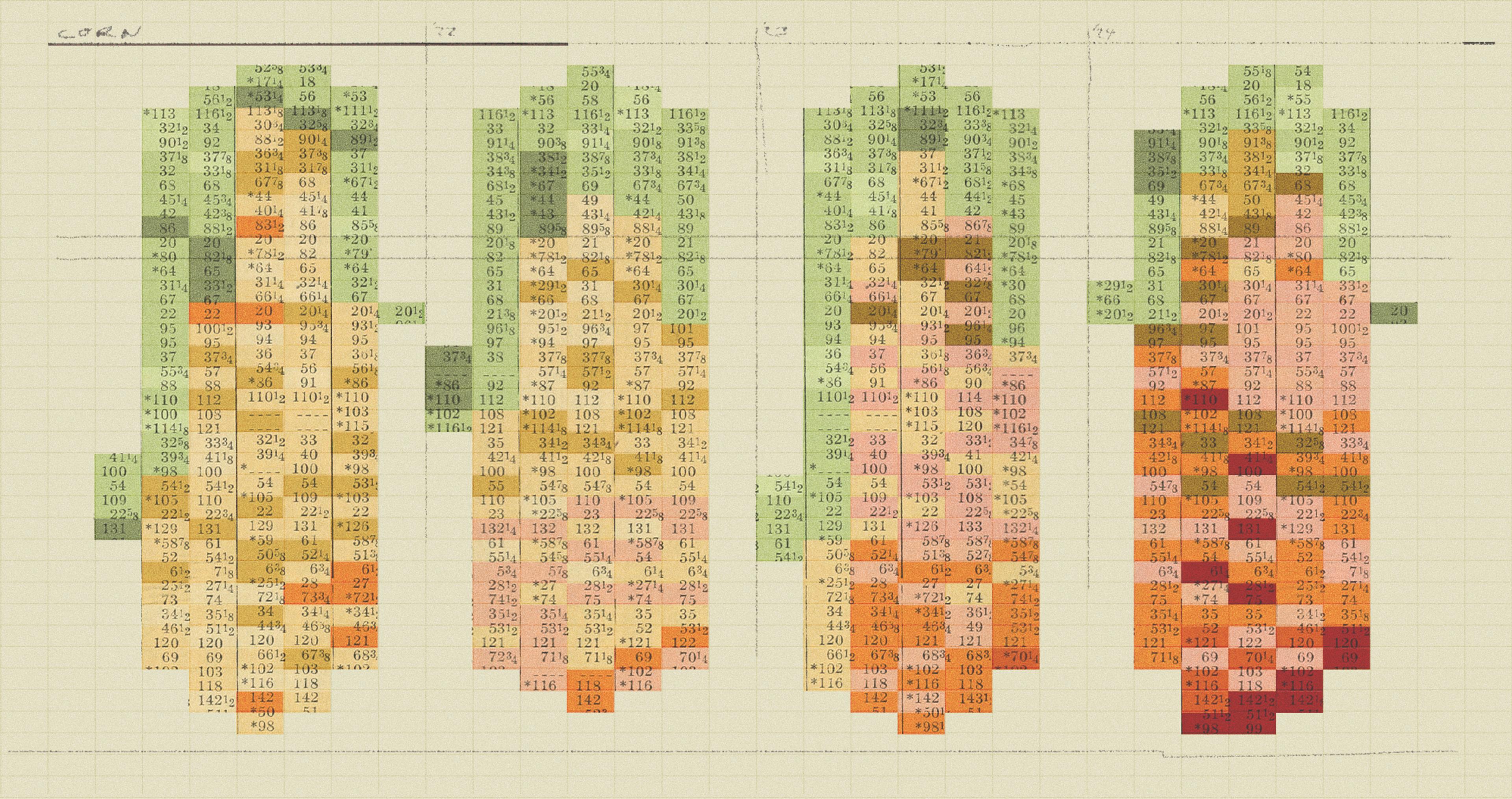

This is one reason there’s a big difference in the number of farms which are “Christmas tree farms” and those which grow Christmas trees in addition to another, more primary business. According to USDA data, there are only 2,880 farms which qualify as Christmas tree-first farms, but a full 15,000 growing and selling at least some Christmas trees.

Seasonal Swap

Another odd aspect of Christmas tree farming is that the absolute busiest time of the year — the month from Thanksgiving to Christmas — is traditionally the off-season for most farmers. For Manix, this is one of its best features. “I wanted to keep my crew employed longer,” he said, and the Christmas tree farm gives another month of work to staff from his other operations.

Around the country, Christmas tree farms serve a similar purpose in the agricultural labor market, said Sidebottom, providing work at a time when it can be harder to come by.

“When harvest comes, Christmas tree farms pick up a lot more people, who are migrant workers who have been working on other things. In North Carolina, apple or sweet potato pickers move over to Christmas trees.”

The work itself is not easy. Christmas trees weigh anywhere from 20 to 50 pounds, and weather in December is unpredictable. Laborers can be “knee deep in mud, it could be raining or snowing,” said Sidebottom, as they load hundreds or thousands of trees into trucks for shipping.

The majority of Christmas trees are purchased at either big box retailers like Walmart and Home Depot, or at bucolic “choose and cut” farms, industry argot for places which let you saw down your own tree (and also sell some pre-cut ones if you’re just visiting for the holiday ambiance), according to the 2021 season recap survey by the NCTA, which polled Americans about their Christmas tree buying habits.

According to data collected by the USDA, the United States has an inventory of 118 million Christmas trees, either in the ground waiting to be harvested or sitting on a lot right waiting for purchase. Oregon is the country’s largest producer, with nearly 300 farms creating an inventory of 35 million trees. The country’s largest farms can ship as many as 100,000 trees in a season; Elysian Hills sells only about 700-900 trees grown on the farm each year.

The U.S. also imports trees, especially from Canada. According to data from the Canadian government, our northern neighbor exported 2.2 million Christmas trees here in 2017 (the latest year for which data is available), valued at $46 million CAD. (To put that number in perspective, that same year, Canada exported $6.44 billion CAD worth of canola oil seeds, $1.5 billion worth of soybeans, and $1.46 billion worth of prepared or preserved potatoes.)

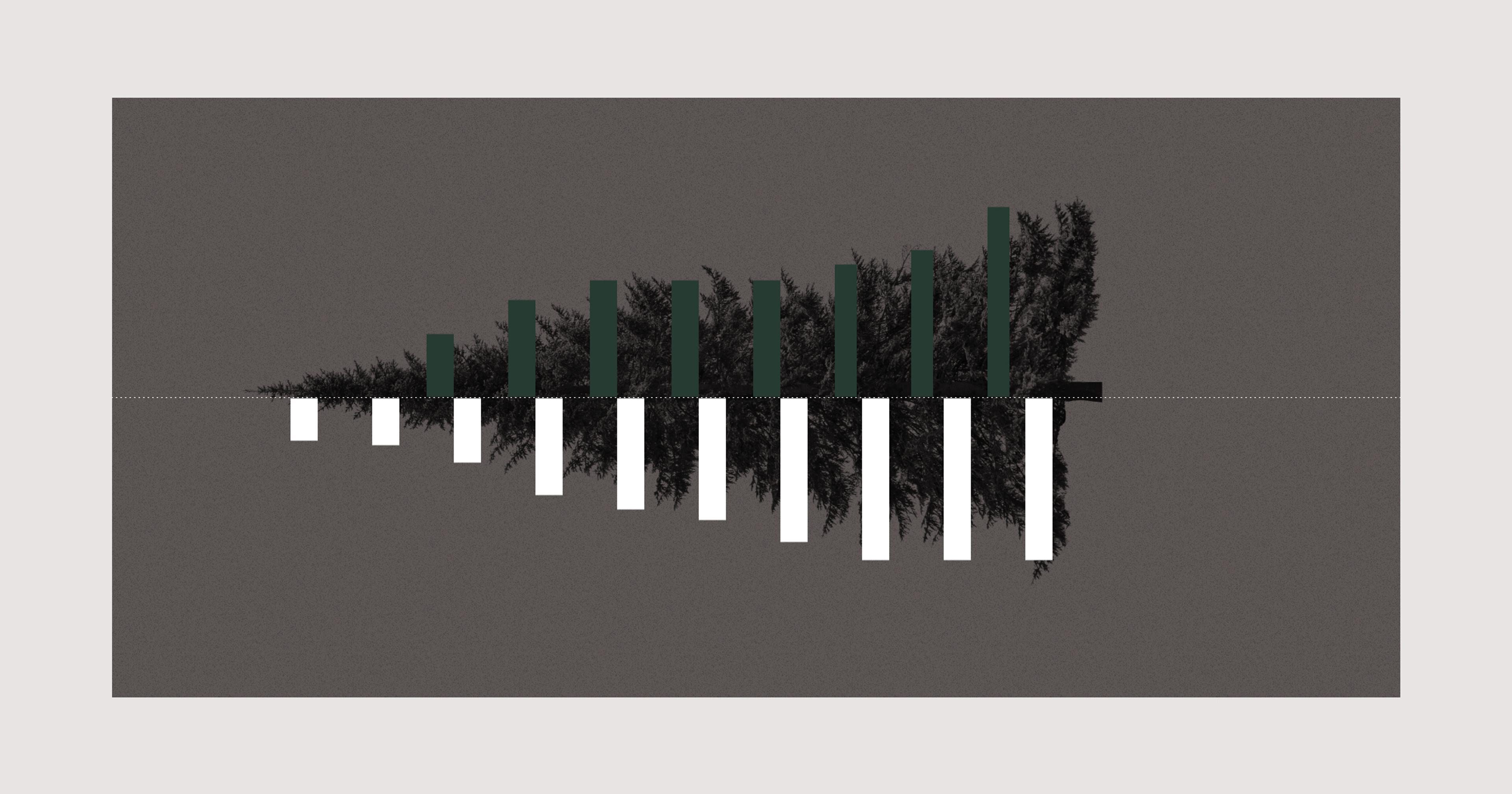

Roots of a Shortage

This year, like many of the past several, we’ve been hit with a barrage of headlines screaming about a shortage of Christmas trees. In fact, this year’s inventory was set years ago when the trees were planted — so is next year’s and the year after that. So to untangle the problem of this “shortage,” we have to wind the clock all the way back to the 2008 financial crisis, explained Sidebottom.

“At that time there was an oversupply of trees and especially large trees,” because of a lack of demand during the economic collapse, she said. “It took several years for that oversupply to come into equilibrium with demand. And so growers were planting fewer trees. The industries that grew the seedlings weren’t selling seedlings, and a lot of them went out of business.” When the economy began its tentative recovery, it took several years for the seedling business to bounce back, sparking a lowered supply of trees which wouldn’t be felt in the market for eight to 10 years.

These factors contributed to a 3% fall in the dollar value of annual sales from 2014-2019, again according to the USDA, even as average prices of Christmas trees have been rising. Just this year, the NCTA predicts retail price increases of 5-10% as farmers deal with inflation. At the same time, Sidebottom said demand has shifted earlier in the season, as the temporal heft of Christmastime in the American imagination has grown and grown, creeping to Thanksgiving or even before.

“When our industry here in North Carolina started in 1957, they would have their annual meetings the 10th of December because nobody was cutting trees until a week or two before Christmas,” she said. Now, it’s common for growers to be completely sold out by the week after Thanksgiving.

Now it’s common for growers to be completely sold out by the week after Thanksgiving.

Exactly on schedule, one week after Thanksgiving, Vermont’s Jac Frost Farm was sold out. Owner Ashley Reherman purchased the farm just two years ago to give her mother her own “little Hallmark movie.”

“This was never anything in my wildest dreams,” she said. “If you had talked to me three years ago when I was a wedding photographer in Baltimore and told me this is what I’d be doing, there’s no way.”

Reherman moved there with her mother, who wanted to retire “somewhere with animals” after years of caring for her wife with Alzheimers. As we spoke, her husband and son were loading the car for the six-hour drive back to Baltimore, where they both still live and where he has a full-time job. Like Manix, she admits the farm wouldn’t work without his supplemental income. But her love for the business transcends simple economics.

“It’s just a very nice way to interact with people,” she said. “This is a very tight-knit community, everybody knows everybody. And people remember you and they remember how you made them feel.”

In a world where our actions are monetized by forces outside our control in ways we barely understand, it is refreshing to find that something which is a reliable part of a certain sector of American life — something which can perennially be counted on to be in serious demand — is mostly operating outside typical capitalist imperatives.

Manix put his motivation very simply: “I dunno. I just love Christmas!”