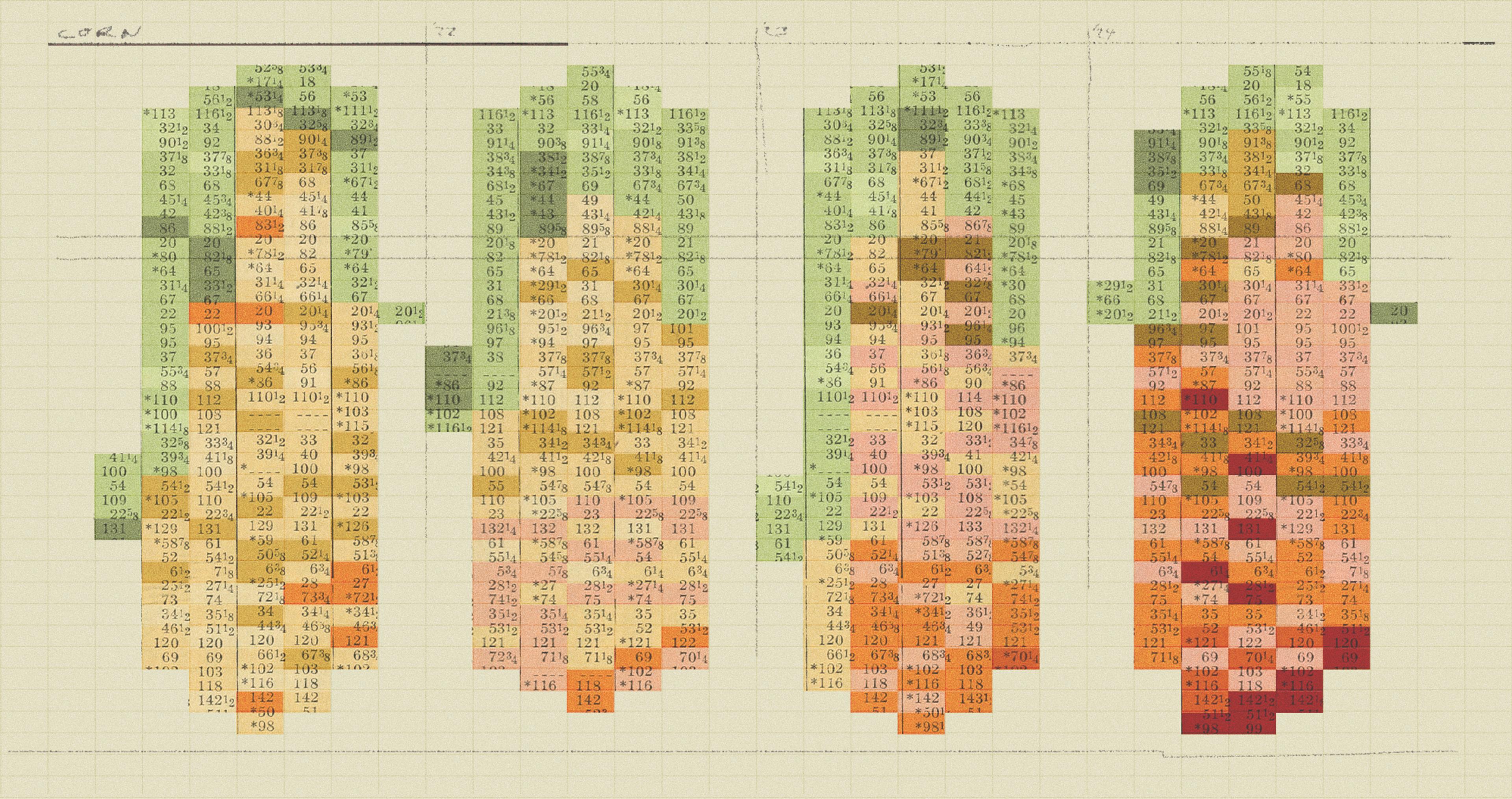

The highest median income for U.S. farmers in the last decade was a meager $296.

Dave Hill has faced sometimes-massive debt since 2010, when he started raising grass-fed beef and growing corn and soy on 150 acres of rented land in Holy Cross, Iowa. His father taught him to drive a tractor and bale hay — “the mechanics of farming,” as he puts it — but farm finance has been a learning curve, to say the least. So for the last decade, Hill hasn’t just been a farmer; he’s worked full time as an engineer, while his wife has provided supplemental income as a part-time claims adjuster.

“I thought I might need a full-time job for five years, six tops, just until we paid down our initial debts. I never thought my wife would need a second job,” Hill said. “This is not how I thought things would go.”

Hill’s experience working essentially two full-time jobs is not novel or unique — far from it, according to new research out of the University of Missouri. Working with reams of data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS), researcher Alan Spell and a team of agribusiness specialists compiled a revealing picture of the increased reliance on second and third jobs for many farmers today.

“It’s not a new phenomenon that farmers may need outside income to make ends meet,” said Spell. “But the number of farmers who rely on off-farm jobs, how important those jobs are to their farm’s survival, and how that has shifted the definition of the rural economy — that was really interesting to see.”

The recent report, titled “The Importance of Off-Farm Income to the Agricultural Economy,” was funded by COBank, a part of the national Farm Credit System. Its goal was not only to investigate farmers’ reliance on secondary income sources, but also to examine what those income sources are, how far people are commuting for off-farm work, and how these patterns are leading to shifts in the texture of rural America.

The farther from a city your farm is, the more precarious your financial situation is likely to be.

In 1974, only 37% of farmers held a primary job off the farm. That number has steadily risen over the decades, up to 56% as of 2017. These numbers are even higher for younger farmers — nearly two out of three rely on off-farm income. Tellingly, a full 82% of farm household income comes from off-farm sources.

“Just about everyone we know is doing some other kind of work on top of farming. And if they aren’t, well I honestly don’t know how they’re making it work,” said AC Shilton, who, in addition to working as a journalist and TV producer, manages to produce grass-fed beef and lamb, pastured turkeys and eggs, and honey on 45 acres in rural Tennessee. Since buying their farm four years ago, Shilton and her husband have both held full-time, non-farm employment. “There is absolutely no way we’d be able to pull this off without outside income.”

Spell’s team dug into some of the underlying reasons for this increased reliance on off-farm work. One particularly stark revelation was that for nearly a decade, from 2011 to 2019, the national median farm income was a negative number almost every year. And the only year that number was positive, 2019, the median was a meager $296.

“Looking at this ERS data was really a lightbulb,” said Spell. “I knew farming was hard, financially. But to see that the typical farm, on a typical year, does not have positive farm income, well that is eye-opening.”

The report also details that farm operators are commuting increasingly longer distances to work, and that the farther from a city your farm is, the more precarious your financial situation is likely to be. Mark Peterson, who farms 500 acres of corn and soy in Stanton, Iowa, said he knows farmers who spend hours commuting to and from their off-farm jobs, like his neighbor who travels well over an hour to teach auto mechanics at a community college. Peterson, who drives tractor-trailers in addition to other off-farm income sources (county supervisor, school bus driver), said he’s lucky his boss lets him keep a truck on his property.

“If I had to head into Omaha every time I got a new [trucking] job, well I’m not sure the economics would make sense,” he said.

Another crucial factor in the need for off-farm employment? Health insurance. In addition to “reliable income,” health care benefits were the top reason for farmers to keep outside jobs — especially important in a profession that’s consistently rated as one of the most dangerous.

“My wife and I just went to the funeral this weekend of her best friend’s son, who was killed in a farming accident,” said Hill. “This is definitely not a job you want to do without health insurance.” Hill said this issue is a constant part of the discussion regarding whether he or his wife can ever leave their outside jobs.

For Spell, an applied social sciences extension professor, some of the most interesting data in his team’s report is how off-farm employment is redefining our understanding of rural and urban life. “When you have so many farmers traveling into cities for work, and urban economies are so reliant on neighboring farmland for their food supply chains, the line between rural and urban gets a lot more blurry,” he said.

Additionally, the very term “rural economy,” which once was used interchangeably with “agricultural economy,” increasingly encompasses a broader, more diverse range of industries. In particular, service industry jobs have outpaced farming as the major source of income in rural areas — especially considering the continued decline in manufacturing jobs.

“Working a second job is nothing new for farmers,” said Spell. “But how that looks now has changed quite a bit.”

Read the full report here.