It has been sold as a cornucopia of additional revenue streams — but it’s often not so easy.

For producers hoping to pull their ledgers into the black by adding petting zoos, pumpkin patches, or barn weddings — commonly considered a surefire way to increase cashflow — the reality is not always easy, or profitable.

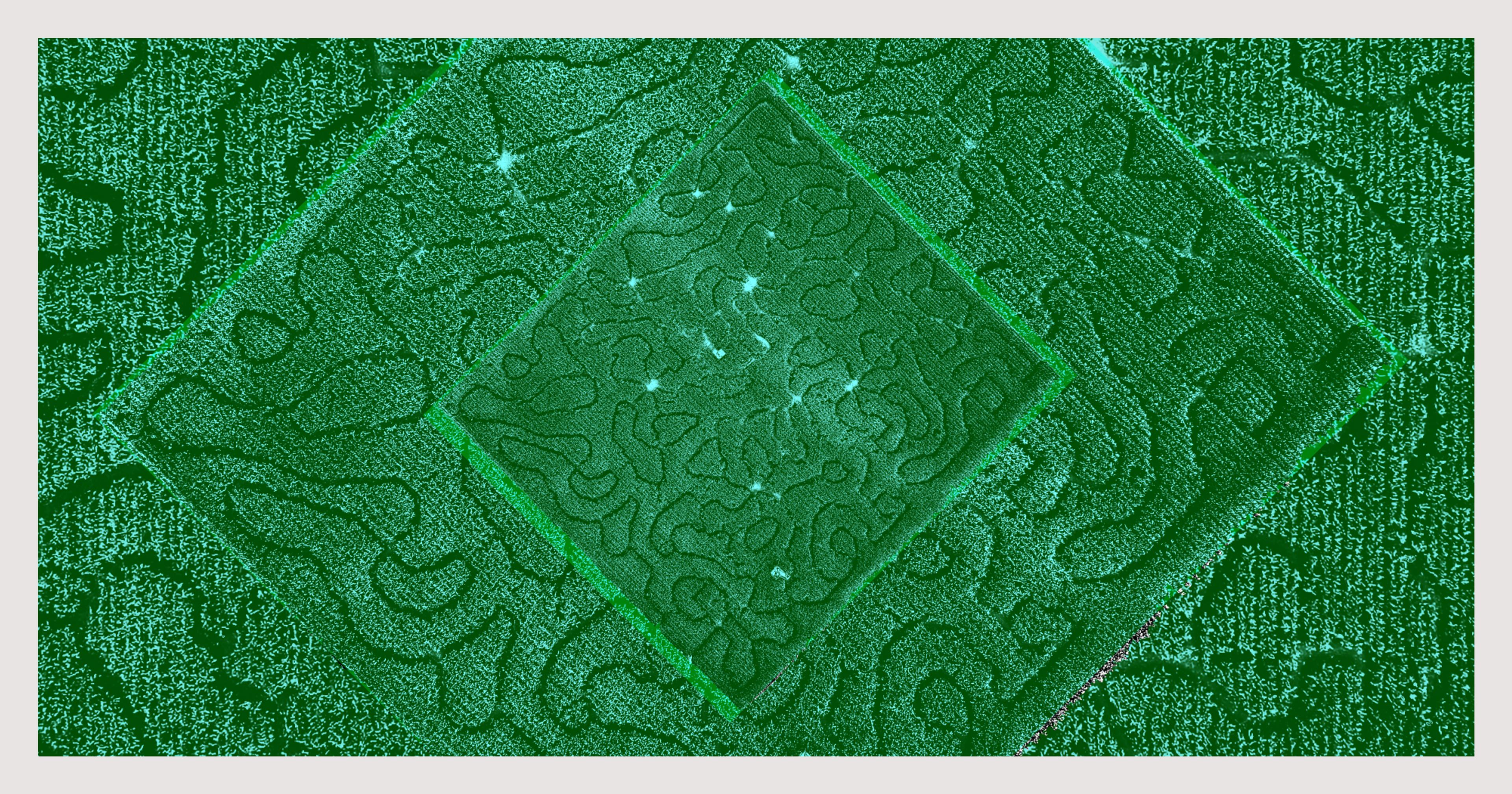

Agritourism is a catch-all term for any on-the-farm activity that invites outside guests — think corn mazes, cafes, or overnight farmstays — and many producers use it as a way to pull in extra cash. According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, 28,575 farms across the country offered agritourism and recreational services of some sort on their land — generating $949 million in sales.

Implementing these side hustles, however, is far from simple. A new study on the agritourism issues facing the aspirational farmer shows that the challenges are many; local bureaucracy can be a major hurdle; and many producers find themselves without any guidance. In short: Agritourism is easier said than done.

“Let’s say that you are a small or medium-sized agricultural operator who would like to move into tourism. This isn’t necessarily something that’s in your toolbox,” said Jane Kolodinsky, director of the Center for Rural Studies at the University of Vermont, which conducted the new research. “If you are a producer, you might be entrepreneurial in production, but you certainly might not have the skills to actually set up how to run a tour, lodging, transportation, etc … There’s a whole set of regulations there.”

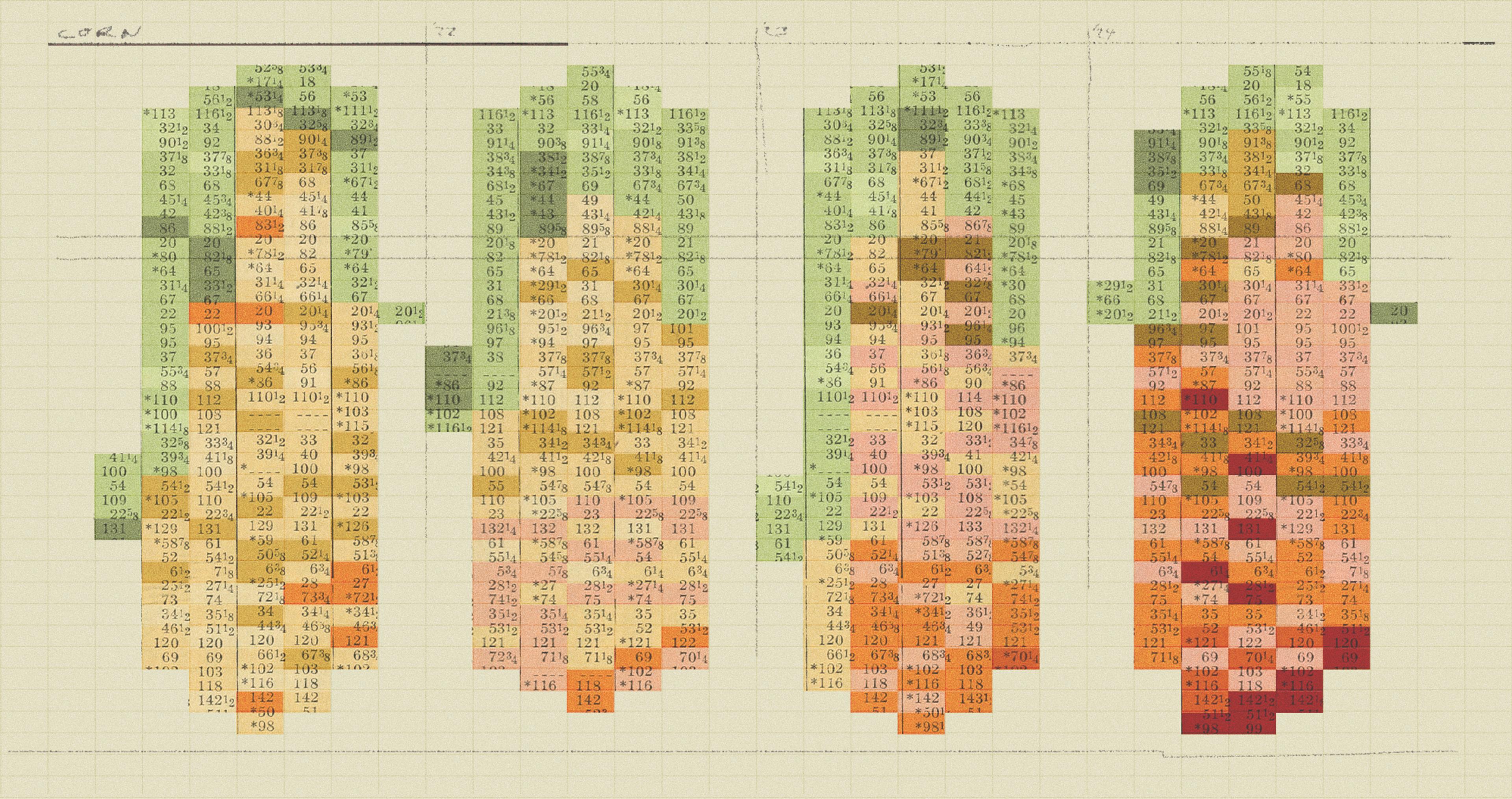

Twenty-six percent of farmers that reported agritourism on their land also reported zero profit from the operation.

Throughout the country, farmers struggle to understand and operate through the intricacies of local zoning and permitting laws that dictate what they can and cannot do on their land.

“It’s an issue all over the U.S.,” said Lisa Chase, natural resources specialist at the University of Vermont Extension. “As farms develop creative enterprises that educate visitors and bring more visitors to their properties, it goes outside the boundaries of what’s typically understood as farming. So that can cause issues for neighbors and their towns as well as on the state level in terms of what’s allowed to take place on a farm and what isn’t.”

Different counties and municipalities have their own land-use laws farmers need to consider when starting up tourism operations, as permits to host guests, serve food, etc., may not be available. Depending on local laws, many activities on land zoned for farming can be prohibited.

Scottie Jones, who started Oregon’s Leaping Lamb Farms with her husband in 2002, said that crossing a county line can be the difference between if activities — like allowing campers on farms — is allowed or illegal. She added that neighbors wary of new development next door can be another unforeseen obstacle. “I usually tell people, ‘Before you do anything, go talk to your neighbors and tell them what you’re going to do.’ Because if you want somebody to tank an application to the county for a permit, your neighbors will do it faster than anybody else can if they don’t like what you’re doing.”

Even after completing the often-arduous setup process, profit is never a guarantee. According to a survey conducted as part of the UVM research, 26% of farmers that reported agritourism on their land also reported zero profit from the operation. This means that just over a quarter of respondents said they brought in revenue from agrotourism operations, but it wasn’t enough to exceed operating costs and pull in a profit.

“It’s extremely important to be properly insured as a business ... I can’t afford to lose my farm because of the guests.”

Decades ago, Beth Kenneth and her husband Bob were early agritourism adopters at their Vermont dairy, Liberty Hill Farm. In 1984, the two opened the doors of their 10-bedroom farmhouse and began to host guests for overnight stays and farm-to-table dinners in hopes of generating enough revenue to stay afloat.

“I needed to diversify the income in order for our farm to survive. And over the last, you know, 39 years, that need to diversify the income has never really ended,” Kenneth said.

UVM’s research found liability issues as a top challenge when opening an agritourism operation just about anywhere in the country. Proper permits and insurance are integral to safeguarding farmers who open their land to visitors or conduct operations outside of typical farming. “You open yourself up to tremendous risk and liability. So it’s extremely important to be properly insured as a business if you’re taking people to your farm into your home. I can’t afford to lose my farm because of the guests,” Kenneth said.

Producers assume responsibility for visitors’ safety when they invite them onto their property, and the activities they offer can impact insurance premiums. For example, if a farmer wanted to add a higher-risk activity like horseback riding tours, they’d need to make sure insurance would cover possible accidents — and pay more for that insurance.

In 2004, Kansas became the first state to enact a liability protection law for producers that offer agritourism activities on their land. Since then, 31 states have put limited liability agritourism laws in place that offer farmers and ranchers immunity if a visitor is hurt while on the farm. Still, each state’s liability laws define agritourism differently and come with a unique set of exceptions to the farmer’s immunity. Producers need a solid understanding of the laws within their state if they want proper liability protection — and that understanding can be hard to come by.

The pivot from farmer to host, marketing manager, travel booker, and tour guide can cause challenges long past the initial business setup.

The marketing and travel booking side of things also isn’t always second nature for farmers, said Jones. For success in agritourism, “You need to understand the world of travel booking and the challenges that can present. If you insist on old-fashioned email and phone calls for communication, it’s likely this will just stay a hobby and never really flesh out into a viable business operation,” she explained. “You need a website. You need social media.”

Farmers listed time management and marketing as the additional top challenges of agritourism, the university’s research showed. In a sense, farmers are entering the hospitality business, putting them in a direct customer-facing role — one that may be new to them. The pivot from farmer to host, marketing manager, travel booker, and tour guide can cause challenges long past the initial business setup.

In Marietta, New York, Evelyn Luebner and her family operate a dairy farm with multiple agritourism attractions, including a pumpkin patch, corn maze, brewery, and bakery. Luebner, who is more comfortable with the cows than the guests, said the customer service side was a learning curve for her.

“Customer service is not my strong suit. I like working with animals,” she said. “I’ve definitely had to make a strong suit over the past few years, and that’s definitely been a struggle for me.”

In an effort to start mitigating these challenges for farmers, Chase and other researchers channeled the results of their studies into a guide to navigating Vermont’s agritourism regulations — something they hope to see nationwide.

“The goal is to actually develop programming that’s tailored enough to meet everybody’s needs, so that they can look it up,” said Kolodinsky. “Problems with permitting? Go here. Need help marketing your operation? Go here. It’s just like any other business, especially if it’s a small business: Entrepreneurs have to be Jack and Jills of all trades. They need to know where to find the information specific to their questions.”