Farmers have been feeding food scraps to poultry for centuries as a way to reduce costs and waste — but a new study shows the practice could also improve gastrointestinal health.

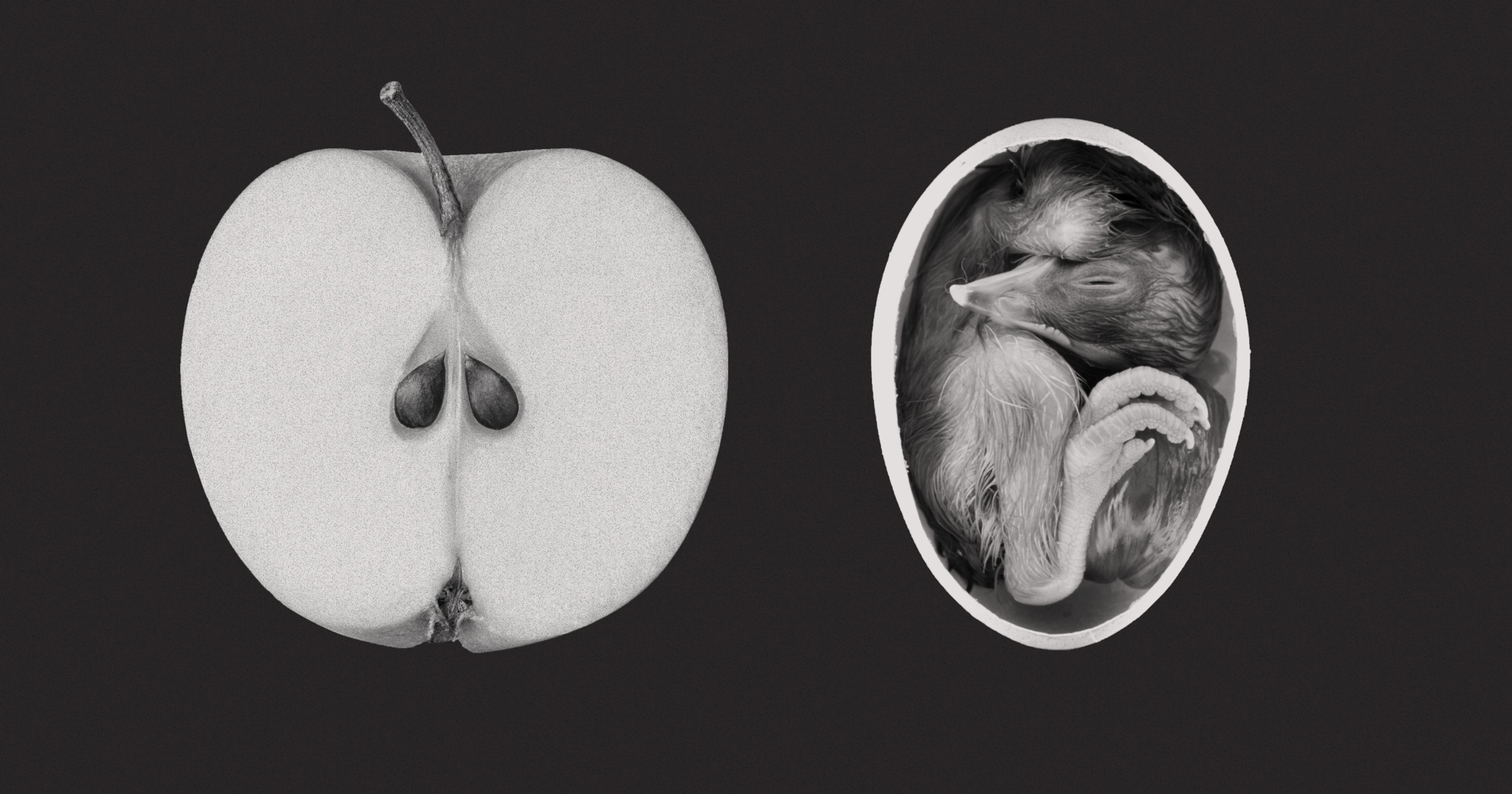

When it comes to keeping livestock healthy — or any living creature, really — gut health is a top priority. Researchers at Cornell had that in mind when they asked themselves if they could repurpose apple pulp and pomace — the fibrous apple bits left over after juicing the fruit — to boost the gastrointestinal health of broiler chickens.

“I would say for most farmers that have livestock, gut health is a big part of what they’re managing,” said Tom Gilbert, who owns and operates Blackdirt Farm in Vermont, which produces pasture-raised eggs, meat birds, garden compost, worm castings, and field crops.

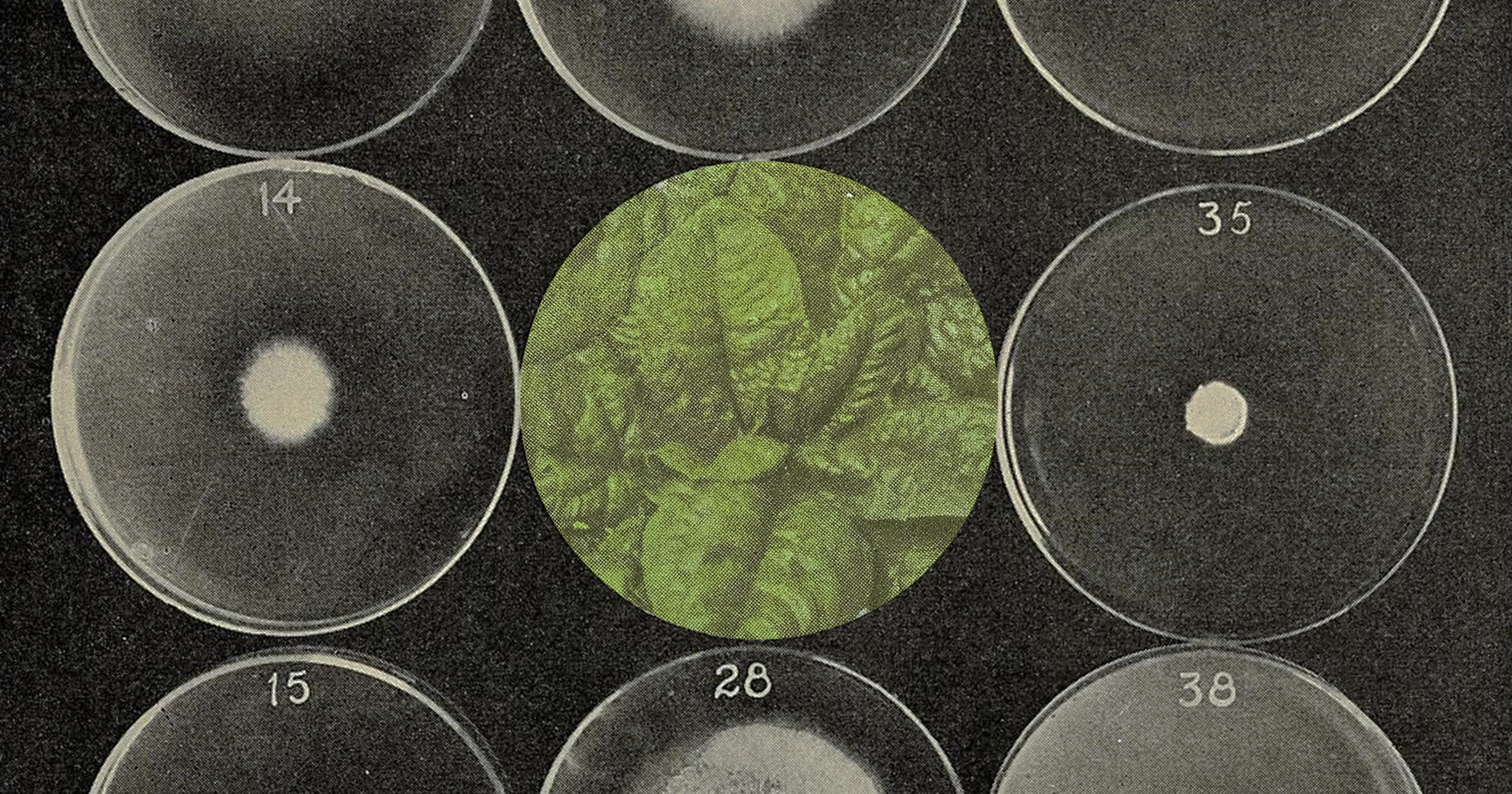

The results of the Cornell study showed that — thanks to phytochemicals and prebiotics within the apples’ chemical makeup — the introduction of apple fiber offers gut bacteria-boosting benefits, which can create a healthier microbiome within a chicken’s GI system. “We can improve poultry’s intestinal functionality by potentially combining pomace in their diet,” said Elad Tako, an associate professor of food science at Cornell and a senior author of the study.

To be clear, chickens didn’t eat apples as part of the process. Instead, researchers used apple pomace to concoct a liquid extract, which they then injected into the amniotic fluid of a chicken embryo in vivo. During a chicken embryo’s incubation period, Tako said, one final phase before hatching involves the embryo drinking the embryonic fluid — effectively triggering its systems to wake up and crack into the world.

“The embryo will then orally consume [the apple extract], and then we can test the effect on the [chicken’s] system,” Tako said. Once the chickens hatched, the team collected samples to test the apples’ success.

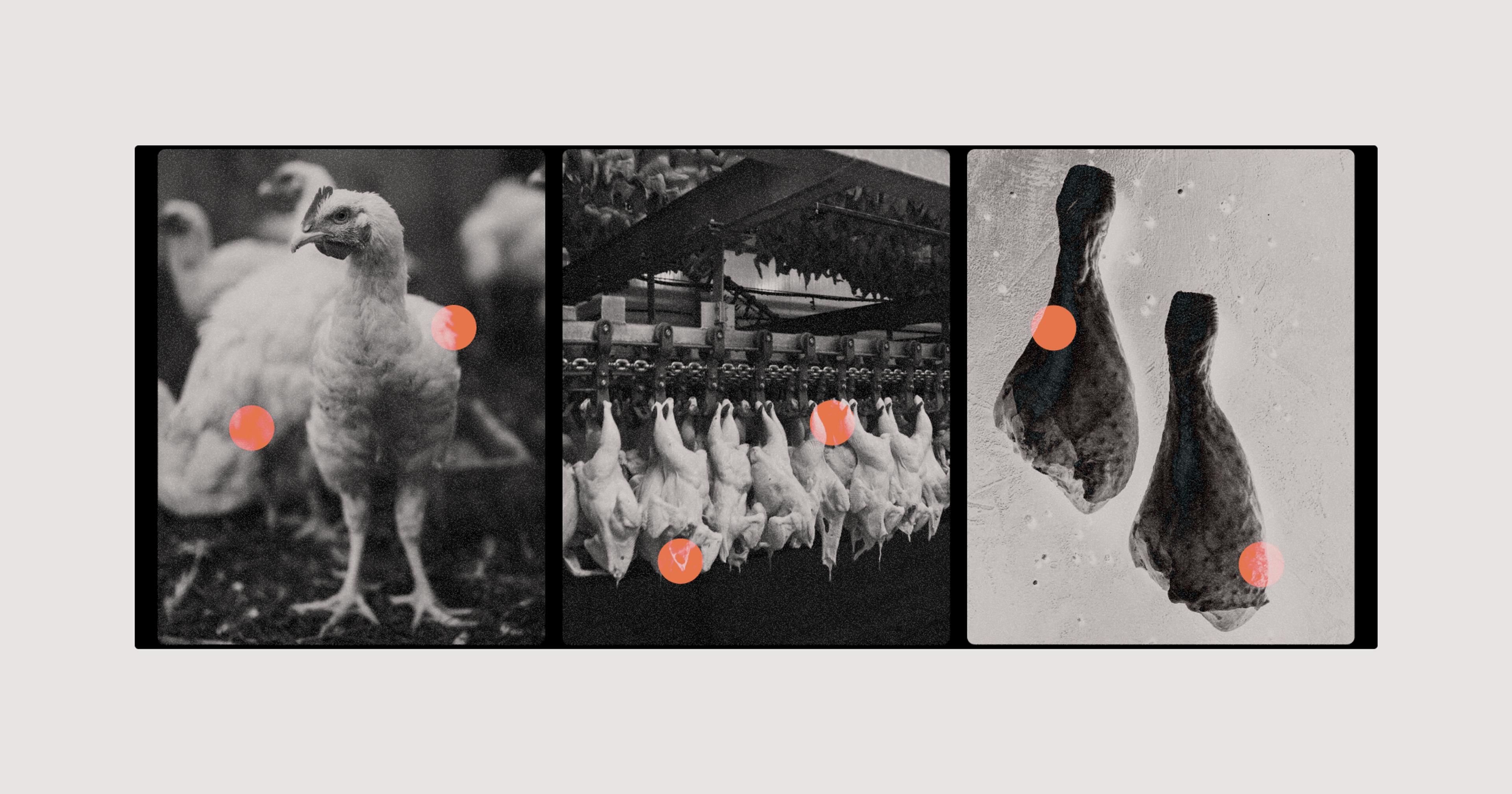

Fostering a healthy gut microbiome — the trillions of microorganisms that live inside the intestinal tract — plays a crucial role in the overall health of all creatures. In chickens, a healthy gut increases the animal’s productivity and can boost a bird’s nutrient production, help the immune system mature, and protect it from pathogens.

The study’s core findings suggested the presence of apples — thanks to compounds like pectin, a soluble fiber in apples that can curb digestive issues and help control cholesterol levels — could speed up the transport system for amino acids in the chickens, and the bioavailability of iron. It also had the potential to increase the population of immunity-boosting microbes in the animal’s large intestine and support the growth of good gut bacteria. And for poultry, a diverse gut microbiome is closely linked to their health as part of a sustainable meat supply.

While feeding chickens table scraps is not a novel practice, producers appreciate this type of research, which helps guide them to the most nutritious options.

“If we had a cider maker that was nearby, I would prioritize having those apples come back here.”

At Blackdirt Farms, the chickens have long enjoyed upcycled food waste as a form of feed. The farm collects about 250-300 containers of discarded food a week from more than 100 businesses and institutions — think grocery stores, local schools, nursing homes, and prisons — within about 40 miles of their land. Instead of feeding the scraps directly to the birds, the farm pre-composts it, or brings it up to 120 degrees before they feed their flock. And Gilbert said research like this is a welcomed resource.

“If we had a cider maker that was nearby, seeing a study like that, I would prioritize having those apples come back here,” Gilbert said.

The chickens‘ health isn’t the only positive outcome of the study. The authors, Tako explained, had another goal in mind when they began their research: reducing the quantity of potentially hazardous food waste. According to EPA data, an estimated 35.3 million tons of wasted food went to landfills in 2018.

Taking into consideration apple pomace alone, nearly 175,350 metric tons of fibrous waste is produced annually and most often ends up in landfills, according to the study. As it breaks down and ferments, the sugar content of substances like apple pomace can alter the carbon-nitrogen ratio of soil, harming the soil’s health. Additionally, the decomposition of food scraps releases methane, a key contributor to greenhouse gas emissions.

Gilbert explained Blackdirt feeds chickens food scraps because it aligns with the farm’s ethos of regenerative agricultural practices and the creation of sustainable food systems, and it honors the chickens’ instinctual eating habits — which are more diverse than just grain. “The premise of this whole thing is not just to utilize waste byproducts, which is a good thing but is really primarily driven by trying to mimic the bird’s natural habitat and foraging tendencies.” The practice also provides practical benefits, Gilbert added, like reducing his feed costs.

“If we can achieve [healthy gut support] in a more natural way — that’s what we are after.”

Tom Watkins, co-owner of Murray McMurray hatchery in Iowa, said that he often feeds table scraps to the 200 chickens he raises at his home. He said studies like this one helps to validate the fruit and veggie-heavy feeding choices for his personal free-range chickens.

Still, both Watkins and Gilbert pointed out the potential pitfalls of apple pomace as chicken feed on a large scale. Gilbert mentioned that apple processors who are not connected to an orchard often buy their apples wholesale, meaning each apple comes with the little sticker you’d find pressed on fruit in your local grocery store. The stickers are notorious for causing issues for composting, and according to Gilbert, they can end up laced into large-production apple pomace, leaving traces of plastics he would not want to feed a chicken.

Watkins noted that on a large scale, there could be more hurdles to work through when using the apple byproduct. “Apples tend to spoil,” he said. He worries that in order to keep a product like apple pomace from rotting on a commercial scale, manufacturers may have to highly process it or add preservatives — he wouldn’t want to feed that kind of product to his chickens.

That being said, local partnerships between cider makers and chicken farmers that reduce long shipping distances and the need for longer-term shelf stability could make the use of apple pomace feasible.

Watkins said most of the hatchery’s clientele run small-scale coops in backyards as opposed to larger operations, and he thinks that is where an apple pomace product could really excel. “I’d love to see feed formulated with [apple] byproducts or something like that. On a smaller scale, I think it’s great, and it’s good for both you and the chickens.”

For now, the research is still in its preliminary stages, Tako cautioned. The next steps will include the addition of apple pomace to feed for already hatched chickens, and that stage will get more into the feasibility of otherwise wasted apple pomace as a larger-scale supplement for chickens’ diets.

“If we can achieve [healthy gut support] in a more natural way, and not by necessarily using antibiotics or other factors that can infiltrate into the food system — that’s what we are after,” he said.