Gardening wheat is reconnecting neighborhoods to their grain, sprouting “pancake patches” and a home-baked way of living.

On a 30-by-15-foot patch of suburban ryegrass, Peter Lovenheim changed his regular mowing routine into a plan for sowing and threshing. For five seasons, Lovenheim transformed his Rochester, New York, backyard — just 425 square feet — into a small field of hard red winter wheat.

Each season, he and his young children threshed wheatberries into grain kernels, ground them into flour, and used it in their baking, a significantly different rhythm than his other gardening. The patch could produce roughly 30 pounds of wheat, about half a bushel, supplying a portion of the families yearly wheat supply.

Backyard wheat has long been tucked away in horticultural guidebooks for dedicated gardeners, and hobbyists fascinated by ancient grains. But this niche practice could revive a fading tradition: wheat production in the United States.

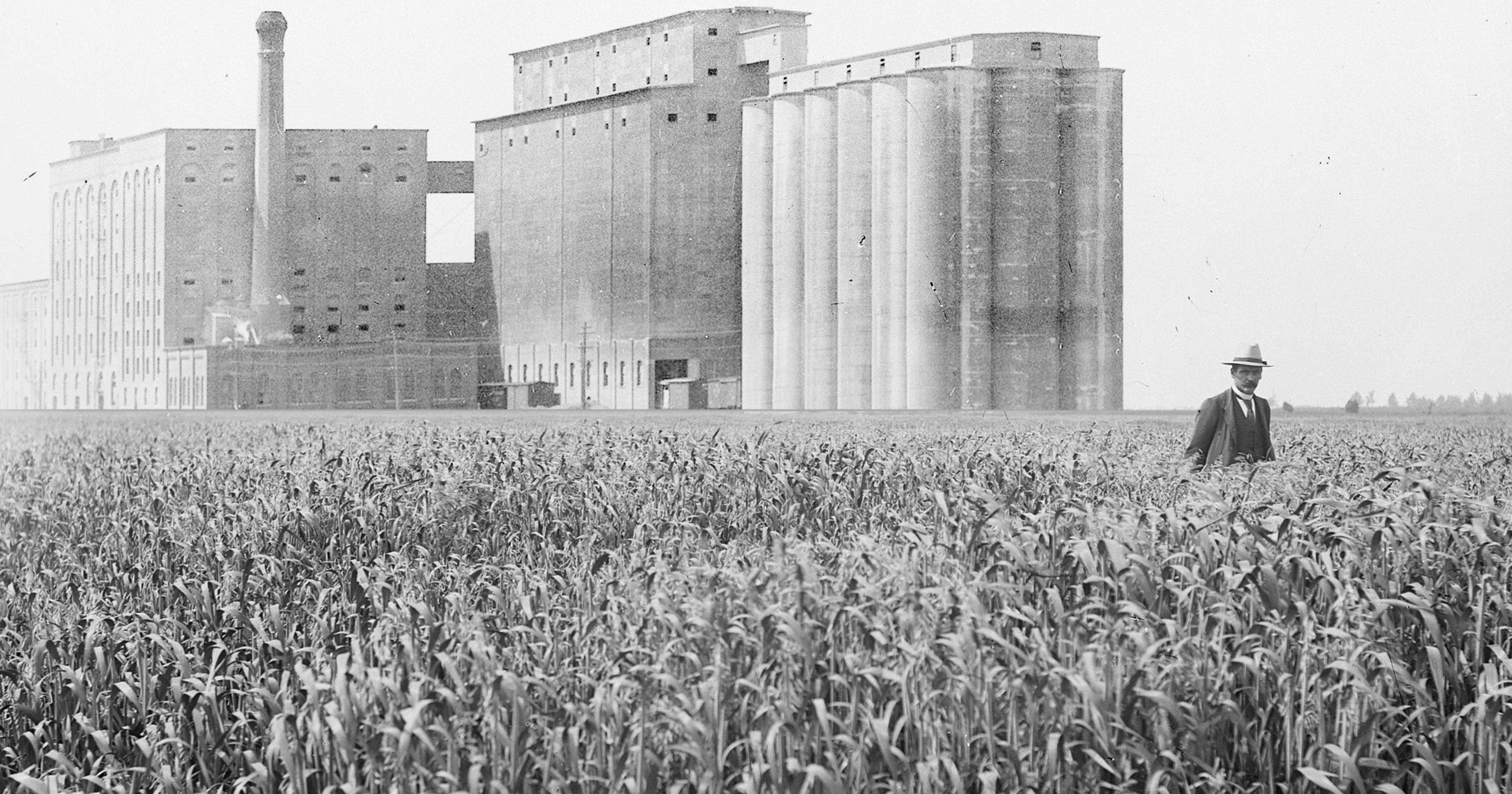

Peaking in 1981, U.S. wheat acreage has since declined by 42 million acres, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. While rising yields have partly offset this decline, global trends tell another story. European precipitation and yield gains have made wheat more competitive, pushing the American commodity market toward other crops — corn and soybeans chief among them.

One of the practice’s earliest advocates, Gene Logsdon, a farm writer from northern Ohio explained: “The reason Americans find it a bit weird to grow small plots of rows of grain in gardens is that they are not used to thinking of grains as food directly derived from the plant, the way they view fruits and vegetables.“

Not limited by yield like a commercial grower, master gardeners have experimented with almost every variety of wheat. Lovenheim’s family harvested their crop each summer, storing kernels for flour blends. When it came time to bake, they poured the grain into a tabletop grinder to make flour for muffins and other baked goods.

“We’re not growing the grains that are necessarily the highest yielding, but they have the best flavor.”

Their first-season harvest party puzzled neighbors unfamiliar with homegrown grain. “Children raised in cities and suburbs typically have no hands-on understanding of where their bread, muffin, cereal — even their oat milk — comes from, unless we show them,” Lovenheim said.

The exact planting routine, depth, and planting density vary depending on whether you access your info from online sources, or Lovenheim’s guide. Ask today’s extension agents or horticulture professors, and most cannot name anyone currently growing backyard wheat. YouTubers and bloggers — some of the newest forms of instant extension — can, however.

As a top five exporter in the world, the U.S. still imports wheat, mainly from Canada, varieties that climatically work better in the North: hard red spring and durum wheatclasses. On the East Coast, white winter wheat for pastries dominate; Kansas and Nebraska rely on hard red winter wheat for bread or all-purpose flour; while the Dakotas grow high-protein spring wheat and pockets of durum for pasta.

The choice of spring versus winter wheat, your environment and soil conditions, and harvesting efficiency all influence the final yield. Just like a high-priced combine cuts, threshes, and winnowing grain crops, the same process happens by hand.

Backyard growers choose their preferred harvesting tools including sickles, scythes, or any curved blade for gathering stalks and cutting. For Lovenheim, that included garden shears. Grains are threshed, which detached kernels from their stalk. Finally winnowing, or the fanning process, separates the edible grain kernels from unwanted chaff.

“Americans find it a bit weird to grow small plots of rows of grain in gardens because they are not used to thinking of grains as food directly derived from the plant.”

In later years, Lovenheim’s plot rotated through buckwheat, oats, soybeans, alfalfa, quinoa, millet, and flax.

Logsdon, a writer and chief gardner, published some of his finest niche books on small grains, like Small-Scale Grain Raising in 1977 and Holy Shit, about manure in the garden. His writing coined the term “pancake patch” — growing enough wheat that a single bundle of harvested wheat could produce a stack of pancakes. At the end of each chapter of his book, he included a pancake recipe using flour made from that grain.

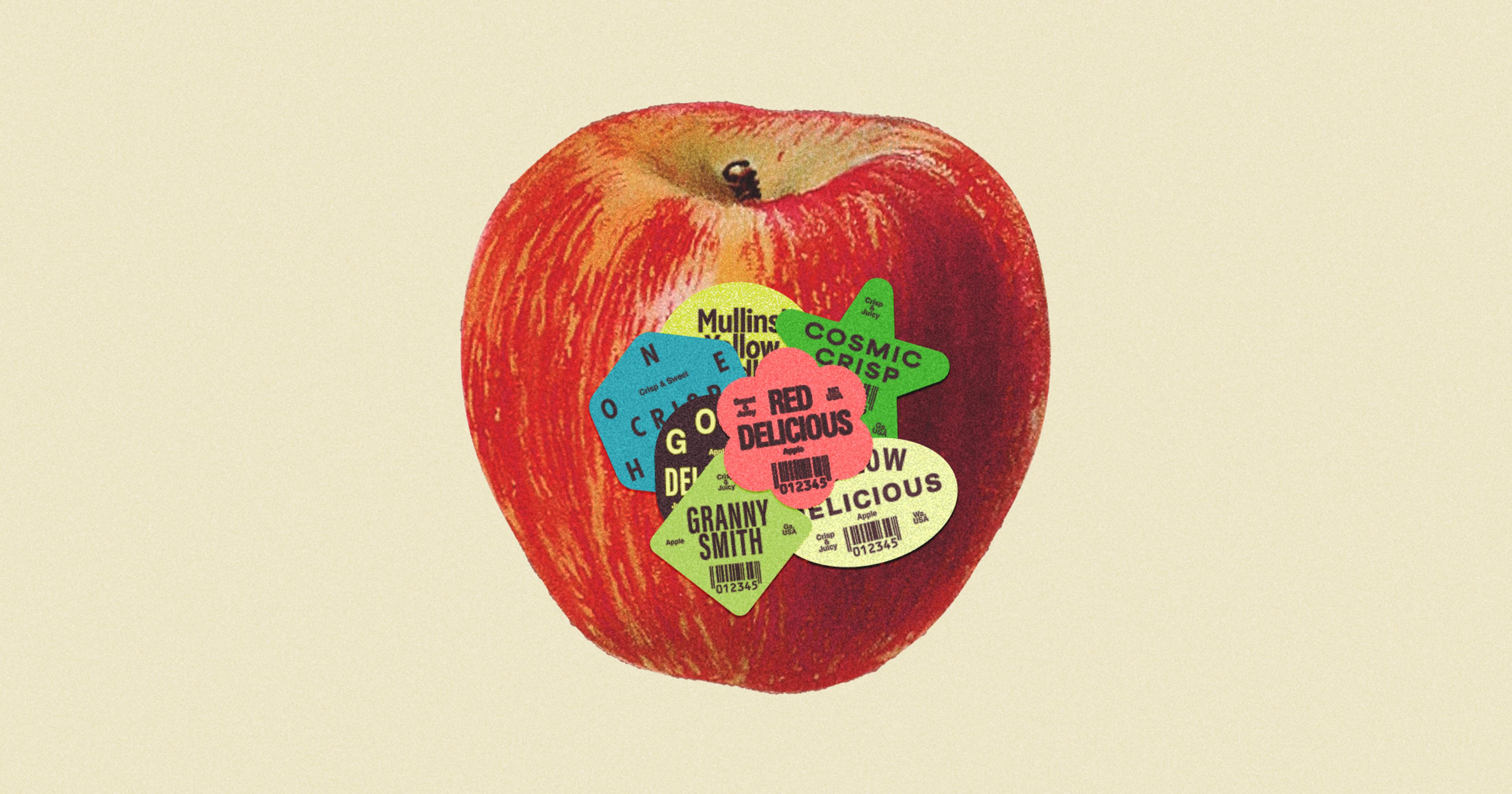

The book’s core principles — choosing varieties based on location and use — haven’t changed, nor have the pancake recipes. But reaching a broader audience for local grain remains a challenge, even though grain still makes up about half of our daily diet.

For consumers, Logsdon explained, “Flour … is purchased like automobiles and pianos,” without a thought of how it’s made. To remedy an agricultural literacy gap like understanding wheat production, small farmers often partner with millers and bakers.

Thor Oechsner farms regenerative organic small grains outside of Newfield, New York. Just like backyard growers, he started with the same experimental mindset on 15 acres. “We’re not growing the grains that are necessarily the highest yielding, but they have the best flavor,” Oechsner said.

“Flour is purchased like automobiles and pianos,” without a thought of how it’s made.

While a lot of wheat production has shifted abroad, specialty markets and local interest keep the crop alive in New York. “We want to grow it closer to where people are using it and revitalize this lost part of New York’s agricultural heritage,” he said.

When the farm started, Oechsner estimated he would need about 400 acres to make the operation viable full-time. When delivering products to any size customer, he admitted there is an undeniable truth. “It’s all about economies of scale,” said Oechsner. His farm now grows about 150 acres each of winter and spring wheat, buckwheat, rye, corn, and soybeans in rotation.

While Oechsner flours are sold to wholesale retailers, supermarket prices on his type of product ring out to almost double the cost than all-purpose flour. Central New Yorkers know his farm and its end product through Wide Awake Bakery, the organic bakery in Ithaca that uses Oechsner-blended bread flours. His farm also stands out for producing spring wheat in New York, a wheat class typically grown in the Dakotas for its short season and high protein content.

But local grain growing, milling, or even backyard production rely on a specific audience: people willing to grow it of all sizes or buy it. Oechsner doesn’t see that demand fading. “Consumers are more discerning than we give them credit for,” he said.