We import almost all of this common kitchen ingredient, but a team of North Carolina researchers is asking: Why not grow it here?

From the Appalachians to the coastal plains, North Carolina’s farming landscape has been dominated by the expected giants: tobacco, soybeans, corn. A team at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, however, has spent the last decade advocating for the potential of the Tarheel State to adopt a spicy, aromatic root more known in the tropics than the Piedmont.

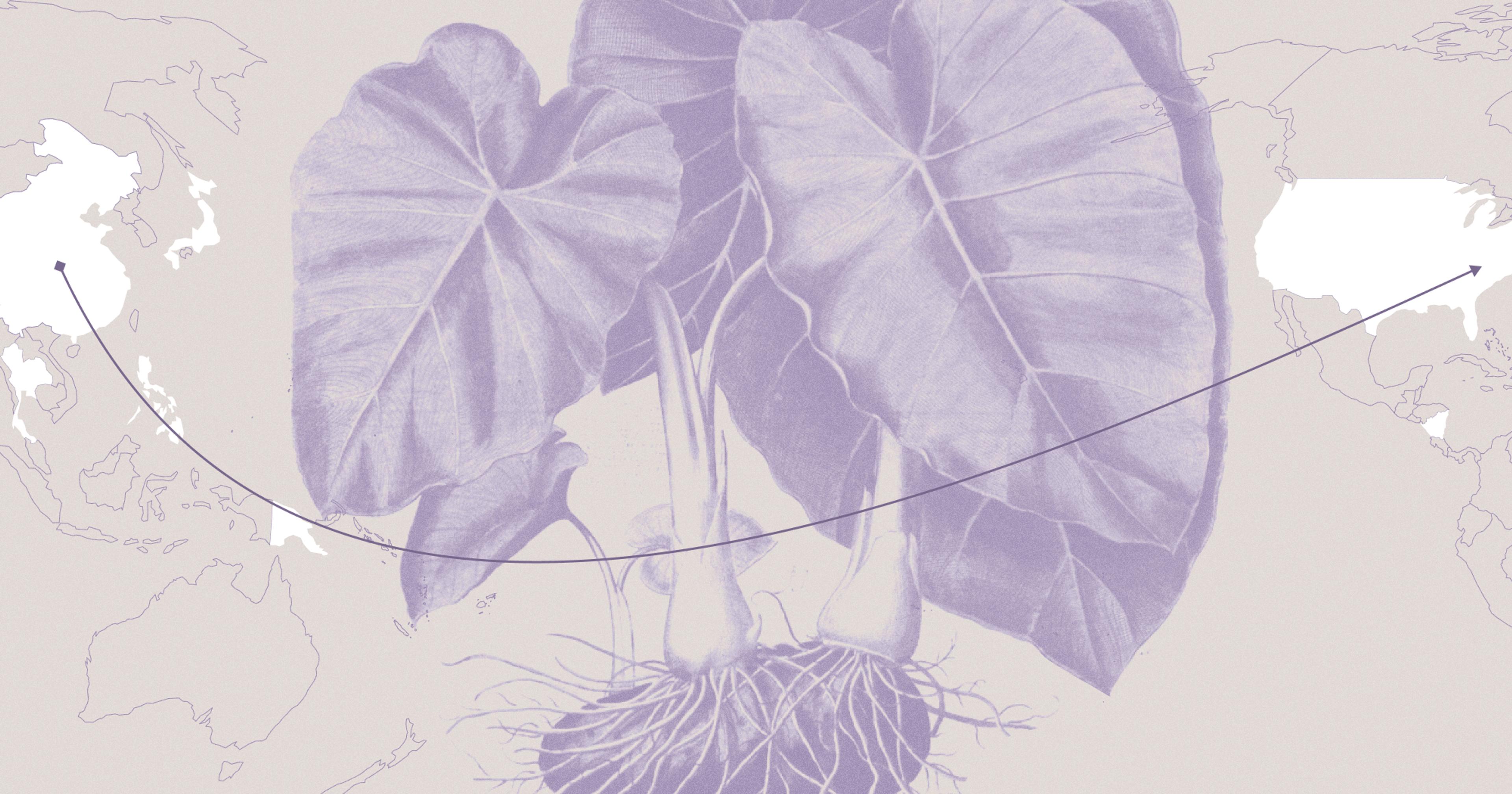

Domestic ginger production has, historically, not been common within driving distance of the Great Smoky Mountains. Humans first domesticated the fibrous, underground stem in Southeast Asia 5,000 years ago, where it became lauded for its myriad health benefits. Polynesian settlers brought the first cultivators east to Hawai’i as a “canoe crop,” along with other subsistence staples like taro, sweet potato, and coconuts. The archipelago’s moist and accommodating soil produced thousands of tons of the root, until bacterial wilt kneecapped the industry over the past couple of decades.

Even at peak production, however, Hawai’i hardly made a dent in global demand. It now produces mere hundreds of tons a year, connected to a mainland that imports as much as one hundred thousand tons annually (and in a world that consumes as much as five million yearly tons).

Seeing the scale of the potential market, an agricultural cadre at North Carolina A&T set to work. They did so under the guiding hand of Guochen Yang — a man who, for four decades of research, recently got dubbed by the American Society for Horticultural Science as a “HortLegend.”

“When I first started, it was basically one bench in the greenhouse and two rows in a high tunnel,” explained Julia Robinson, Yang’s research technician, lab manager, and “right hand” who also researches black cohosh, a plant native to the region and whose biology serves as a helpful ginger analog. Ten years down the road these modest beginnings have expanded to two high tunnels, studies on what color shade helps encourage ginger’s growth, explorations of its viability in wooded areas, and development of one of Yang’s scientific specialties, known as “micropropagation.”

As a form of tissue culture, micropropagation utilizes small batches of cells from a parent plant to produce genetically uniform flora, often on a mass-produced scale. It’s a wheelhouse that may prove exceedingly useful when trying to instigate a novel agricultural market — especially for a root that could inhabit pockets of mountainous, textured terrain in the U.S. Southeast.

The white-coated world of academic inquiry comes with substantially more guardrails and margin for error than anxious farmers tend to enjoy.

Yang’s “left hand,” meanwhile, has been with him for even longer: William Lashley IV has been part of Yang’s lab for the past 12 years, from some of the earliest days of his undergraduate career, even receiving tuition assistance out of Yang’s own grant money. When colloquially described as Lashley’s “Greensboro uncle,” Yang and Lashley quickly moved to clarify.

“Not ‘uncle,’ that’s a too-little title,” Yang laughed. “Greensboro dad.”

Ginger makes for a fertile field for experimentation. “It’s been a very exciting process to see the research evolve, from the basic questions to where we are today,” Lashley said. For his own PhD, one of Lashley’s objectives has been to investigate how various shades and intensities of light — red, blue, yellow, and green — can impact the growth, yields, and physiology of ginger.

But the white-coated world of academic inquiry comes with substantially more guardrails and margin for error than anxious farmers tend to enjoy. “Even though we are promoting and advocating for this, we try to — as a public institution — make some mistakes before the farmers do,” Yang explained. “You have to really evaluate, because each farm has a different situation: what type of soil you have, what kind of facility, your labor force. It really does need intensive care.”

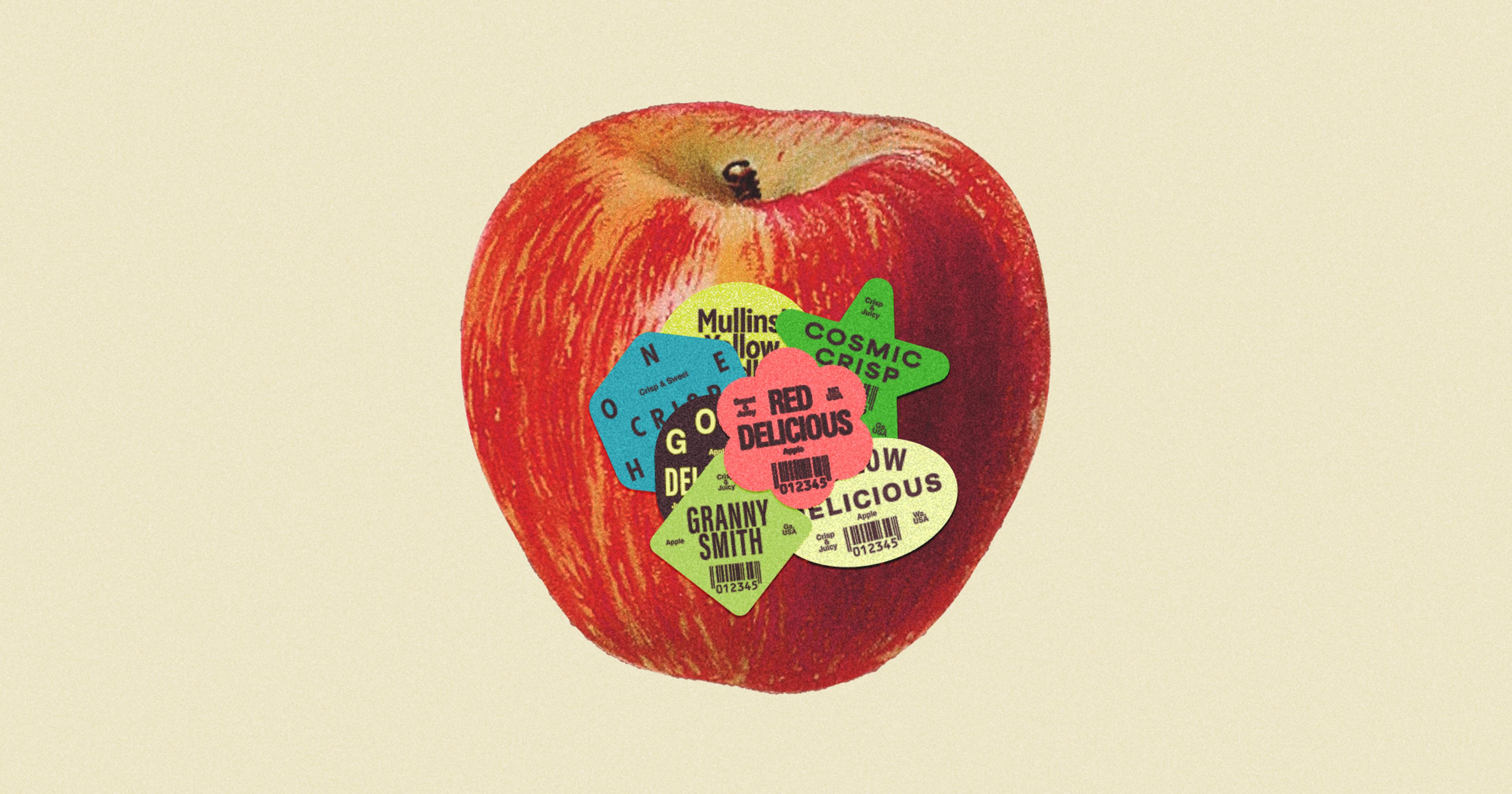

Translating these insights from the lab to the field, meanwhile, often requires some skilled interpretation. Yang’s former student, Trequan McGee, often provides this critical interface in his work as a horticulture extension specialist — especially in the university’s “Ginger Field Days,” which has hosted as many as a hundred rhizome-curious growers. There, folks like McGee stand by to explain the nitty-gritty details of tending to a novel crop that can fetch as much as 18 dollars a pound, and appear in “value-added products” like teas, candies, ice creams, and even beer.

Another of Yang’s former students, Michael Rayburn, has also been at the front lines of boosting the rhizome’s budding profile. After starting Rayburn Farms as a pumpkin patch in 2014 (with his partner Lauren, also an NC A&T alum), Michael’s work connected him with local brewers whose experimental beer flavors would help kickstart a North Carolina-born model now known as “plow to pint,” in which breweries fill their vats with the harvest of local farmers.

At local farmer’s markets, ginger had long gone unappreciated as a viable crop in its own right, often serving merely as an asymmetric splash of color on vendors’ tables.

At local farmer’s markets, ginger had long gone unappreciated as a viable crop in its own right, often serving merely as an asymmetric splash of color on vendors’ tables. And as Rayburn’s growing rolodex of brewery contacts worked to spice up their beverages with home-grown herbs, he slowly learned to navigate the knobby crop’s logistical idiosyncrasies from the ground up (or down, rather).

“It’s more labor-intensive in both weeding and harvesting,” Rayburn cautioned. “You can’t weed it with a hoe, because the rhizomes don’t grow in a predictable way: They go in all different directions, and you can easily nick them, so you kind of have to get in there and hand weed. That takes time.”

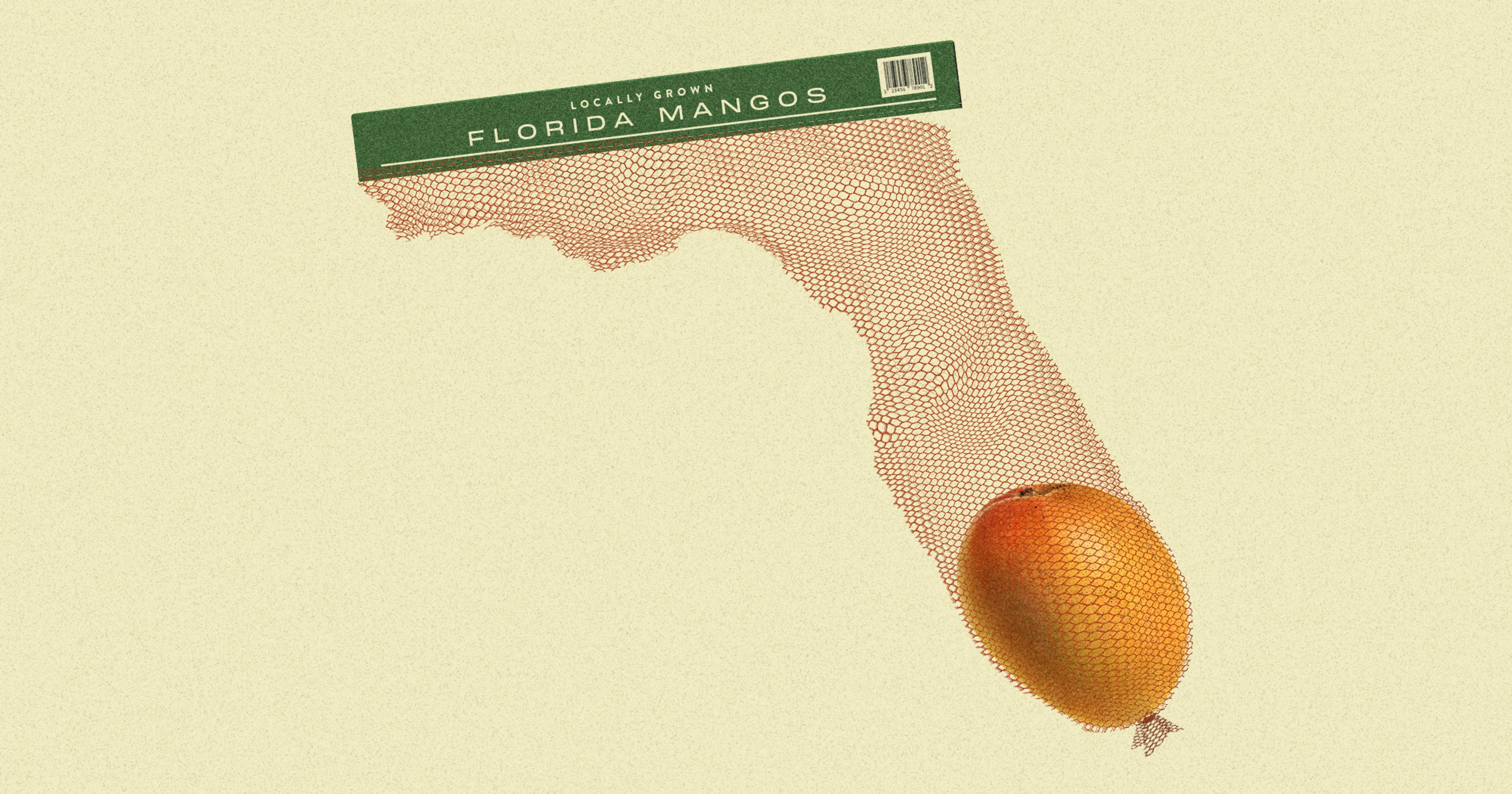

Ginger’s versatility, however, may still prove ideal for smaller, resourceful farmers: a small footprint per plant; flesh that can be used for candies or tea; and sap that can be utilized by everyone from breweries to chocolatiers. On a commercial scale, meanwhile, Rayburn suspects that larger Southeastern farms might eventually be able to compete with international competitors like Brazil and Peru, even with a shorter growing season. He is quick to point out, however, that ginger should not be viewed as a “new golden ticket,” as many novel high-value crops can sometimes be portrayed.

“With a crop like ginger, I wouldn’t suggest someone to go and plant any large acreage [without first] getting your hands dirty. Get some experience, get familiar with it, before you expand that production,” McGee said. “But what we’ve seen is that, overall, it’s a pretty resilient crop. It really has adaptability.”

That’s not to say that the region doesn’t face its own unique challenges. In the wake of Hurricane Helene stressing the soil (and traumatizing local farmers), Rayburn almost declined to plant any ginger at all this year. Yang’s lab, however, stepped in to provide him with enough seed that Rayburn can comfortably supply a local soda company, Waynesville Soda Jerks.

Even a decade into his ginger journey — and with Lashley having just defended his thesis, as the first ever PhD in the university’s horticulture program — Yang and his team feel like they are only just getting started, both in their research and ginger’s Tarheel potential. “There are so many scientific questions that need to be answered: diseases, pests, nutrient level, irrigation and watering, phytochemical context under different lighting conditions. All those details,” Yang explained.

“Even though I’m old, I’m very active and very sharp,” Yang declared. “For ginger research, I will not change direction, because there are so many questions I can see that need to be answered.”