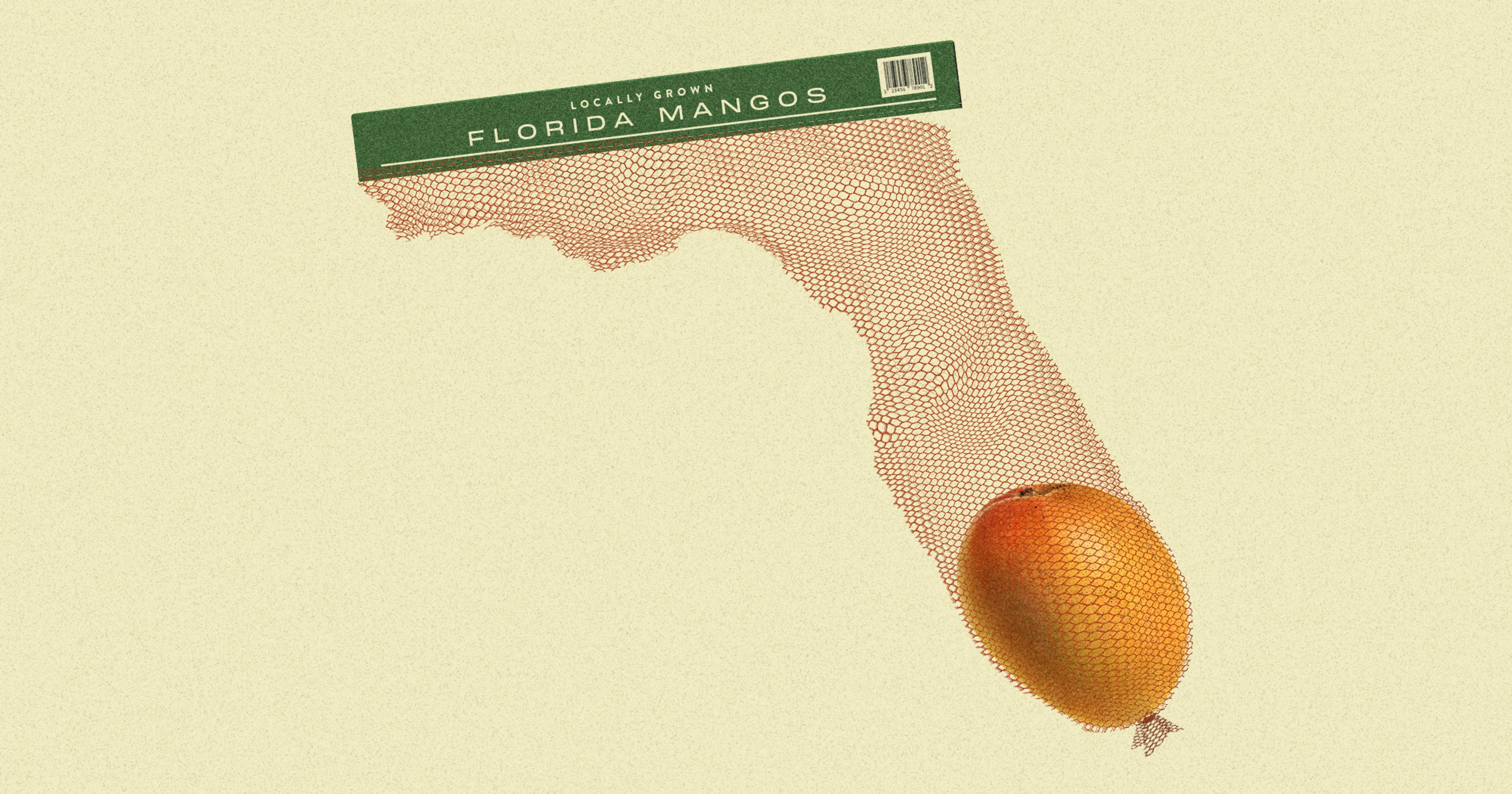

California producers are reporting up to 70% crop loss from grasshoppers. Where is the federal management agency that’s designed to assist with this very problem?

A new generation is currently emerging across the rangelands of northern California, and it’s a hungry one. Some new generations inspire hope for the future. This one, however, bears the stench of destruction — or, in some cases, onions.

“Some producers walk out in spring and summer and can smell the onions, because the grasshoppers are eating them so viciously,” said Modoc County natural resources advisor Laura Snell of her region in California’s far northeast. She works for the University of California Cooperative Extension. “You can smell the grasshoppers eating your vegetables. No one feels good about that.”

Snell first spoke with Offrange last fall, after a particularly devastating season for California and seven other nearby states. A press release from last summer said her county had been “invaded” by grasshoppers, a voracious critter that will consume practically anything growing out of the ground, and lots of it. Just 30 pounds of grasshoppers will eat the same amount of vegetation as one 600-pound cow. Modoc was listed among eight other northern California counties as some of the worst hit. And that was their fifth consecutive year facing a grasshopper infestation — now they’re closing in on a sixth.

It was also in the fall when the pods now hatching this generation of grasshoppers were laid. The most effective time to try to stop the spread of the pests is between then and the spring, when they gestate from crawling nymphs into adults that can fly 15 miles or more. But the bureaucratic pest management systems in place rarely operate on that timeline. And the farmers and ranchers of Modoc County are paying a steep price.

Snell has watched as what once was an issue only for rangelands, grasslands, and hay production now disrupts every realm of local agriculture. Last year, the county lost 30 percent of its crops to grasshopper damage alone, with some producers reporting closer to 70 percent crop loss. Also suffering is the local population of bees, which tend to spend summers up there in the mountains. But damage to early crops and flowers meant 2024 was the first year Snell and her team observed a major hit to honey producers. “You can see the effects at the now-sparse local farmers markets and food co-ops,” she said.

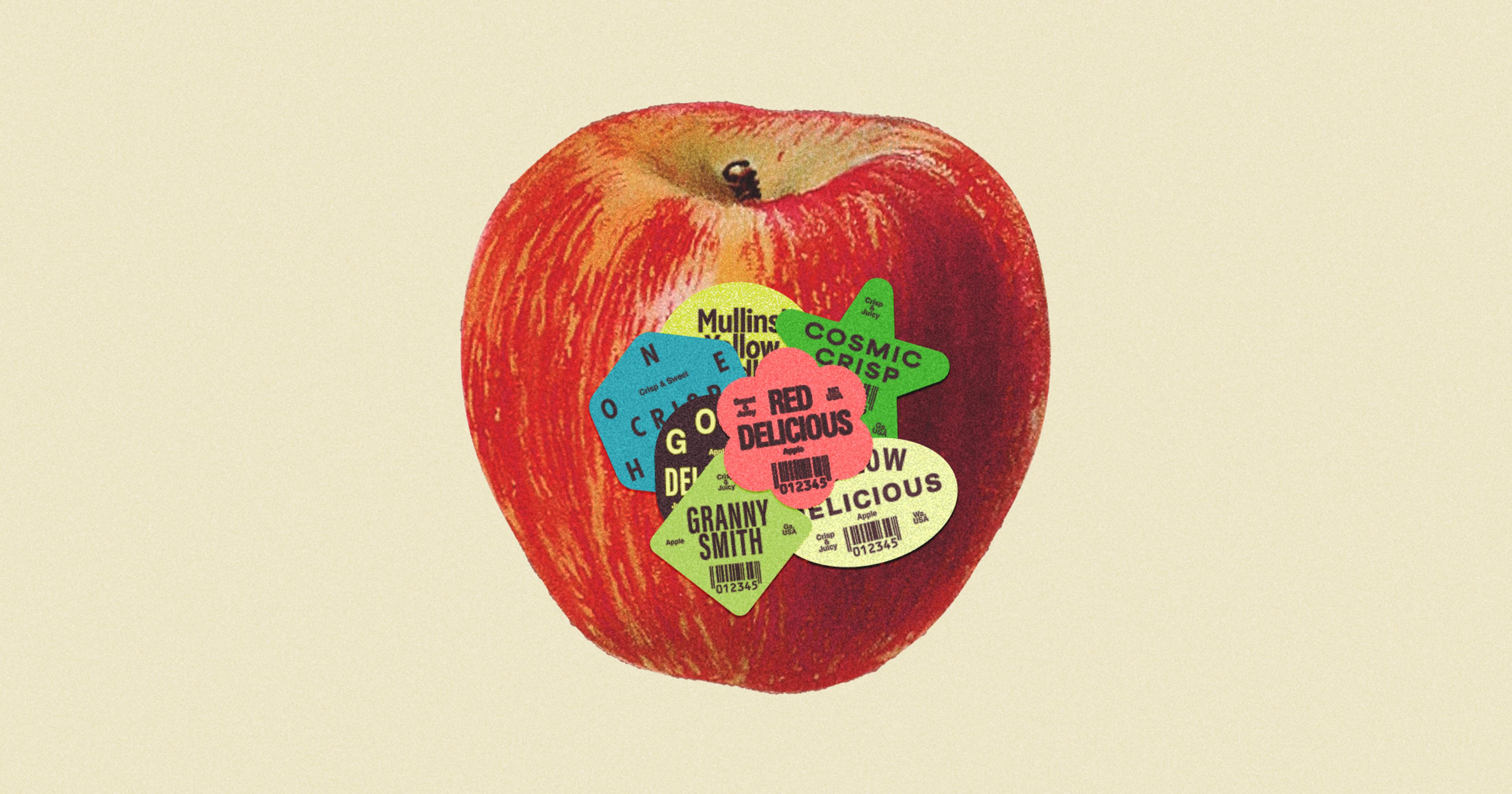

The pests themselves aren’t new to the region, but the rate and persistence of their spread is. For generations, grasshopper invasions were cyclical, with something like one bad grasshopper year for every five good years — and existing guidance on how to manage them reflects that. But even as the county enters its sixth straight season of grasshopper hell — with the insects falling, as one local farmer put it to The Los Angeles Times, “like hail” — local authorities say they are limited in their ability to fix it.

Though Snell and her colleagues have tried, the federal agency devoted to grasshopper management — USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) — has proved difficult to recruit. Each year the county needs to request an environmental assessment that would clearly detail the scope of the problem and lay out a plan of action. But rarely is it completed and approved in time to have a meaningful effect on grasshopper containment.

“You can smell the grasshoppers eating your vegetables. No one feels good about that.”

Unlike its neighbors in states like Oregon, Arizona, and Nevada, California doesn’t have a standing abatement program in place that would allow it to address this issue at the necessary scale and with the necessary speed. Reporting from the LA Times last year states that “California discontinued its abatement program more than 50 years ago because the grasshoppers had stopped becoming an issue until their recent return.” Without it, the county is forced to file ad hoc requests, which are very hit-or-miss.

Modoc County’s agricultural commissioner Heather Kelly said that without an environmental assessment in place, the county’s pest monitoring efforts are insufficient. With help from APHIS, they could “immediately go into action and make the appropriate applications so it doesn’t get beyond that property and damage adjacent crops.”

Though nothing when it comes to grasshopper abatement appears to happen on a very immediate, or linear, scale.

In an email, APHIS’s National Policy Manager William Wesela wrote that in May 2024 his office did send grasshopper experts from APHIS Oregon down to survey for grasshoppers at the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, where “populations of potentially damaging grasshoppers” were identified. But the wildlife refuge doesn’t technically contain any rangeland, a congressionally mandated stipulation of APHIS’s jurisdiction. Consequently, APHIS was unable to assist with treatments, which typically involve the application of an insecticide like carbaryl, diflubenzuron, malathion, or chlorantraniliprole.

Later last summer, APHIS did some surveys of Modoc County’s portions of the Modoc National Forest, where they found a different species of grasshopper and therefore determined it “would not benefit the adjacent cropland” to treat it.

Just 30 pounds of grasshoppers will eat the same amount of vegetation as one 600-pound cow.

Wesela said APHIS is “considering an environmental assessment for Modoc County” on an ongoing basis, though it will be a challenge to pursue because “historically, APHIS has not seen grasshopper activity in this area of the country.” He added that grasshopper populations are surveyed annually in states where outbreaks are “common.” But in states like California, he said surveys may be needed “when outbreaks occur” — which, on the grasshopper’s timeline, is already too late. But after nearly six straight years of catastrophic invasion in northeast California, it’s hard to know what the agency considers “historic” or “common.”

As outdated as these abatement policies now seem, the science for monitoring and understanding these insects and their behaviors hasn’t quite kept up either. No one is comfortable saying definitively what has caused the extended outbreak, but the strongest hypothesis appears to be drought, made more extreme by climate change. When the soils are wetter, for example, a naturally occurring fungicide keeps the grasshopper populations at bay.

Without better, more proactive solutions coming from the top, pesticides and insecticides are filling the treatment gap for the average solution-starved producer.

Of course, some science indicates that synthetic pesticides ultimately worsen drought by disrupting the soil biome. That partially explains why the California Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR) is currently rolling out a new phase of its Sustainable Pest Management strategy, meant to “increase the availability of sustainable pest management alternatives [...] to replace the highest risk pesticide uses by 2050,” according to an email from DPR deputy director Sapna Thottathil.

She continued: “As climate change introduces new and increasing pest pressures, current tools decline in efficacy, and scientific studies identify potential risks that require restrictions on high-risk pesticides,” DPR will work alongside state, federal, and local agencies to improve “pest prevention, management of invasive species and other pests, and ongoing work to promote healthy soils and climate-smart agriculture.”

“You can see the effects at the now-sparse local farmers markets and food co-ops.”

While this strategy may have an overall benefit in the long run, it’s left some producers fearful that they may lose access to the only tool that’s had even a remote impact on the grasshopper epidemic in the short term. As their desperation grows, they’re even turning to ChatGPT for answers — which means Snell spent last summer debunking a bunch of online myths.

“It was saying dust your plants with flour and then the grasshoppers will choke on the flour and die,” Snell said. “In good ChatGPT style it had cartoon pictures of grasshoppers choking on flour.”

But flour isn’t going to cut it. The only real solution lies in proactive land management — not reactive surveying, spraying, or the sprinkling of baking supplies. The leaders of Modoc County know this, but have had trouble finding partners with the resources and the will to help. Snell predicted her county was unlikely to get increased federal support for grasshoppers this fiscal year. And with the tumultuous start to the second Trump administration, federal funding may be even harder to come by. Wesela from APHIS said he preferred “not to speculate” on the matter, though shortly after his correspondence, massive cuts were made to the agency’s workforce.

The grasshopper management program is over 90 years old, which could be seen as an asset or a handicap. But without accounting for modern challenges, climate and environmental changes among them, it will continue to fail to protect vulnerable places like Modoc County. In the meantime, Snell and others like her will be forced to rely on 40-year-old science that claims grasshopper invasions will simply cycle through, run their course, and disappear.

“Some of our changes with climate, in terms of moisture and temperature — it’s not the same ag as it was 50 years ago,” she said. “That resource from the federal government that says, ‘It’s just gonna be cyclic, don’t worry,’ it’s not providing comfort to the producers because they’ve seen it on the ground here year after year.”