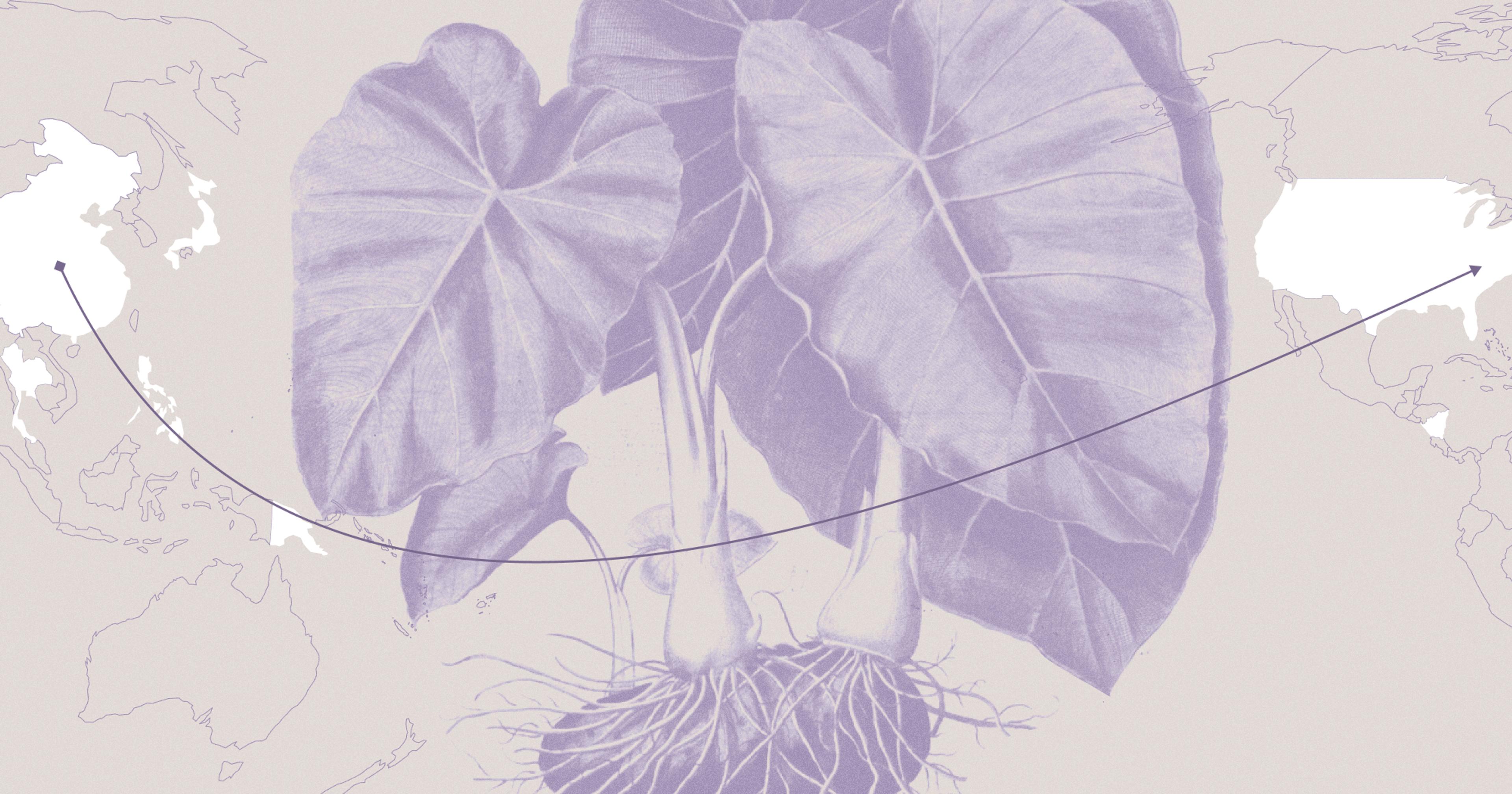

U.S. companies want Southern farmers to plant species of this grass that is native to Asia. Experts say it’s a disastrously bad idea.

“Bamboo farming in America is a terrific idea,” exhorts a blog post from a bamboo consultant in California. Not only does it grow well on land that farmers have traditionally planted corn on, it “holds great promise for American farmers looking to diversify their acreage.”

Similarly rosy assessments have been turning up lately among a handful of small U.S. companies. They vociferously encourage farmers to start planting this “green gold,” which they tout for being sustainable, easy to grow, and quickly profitable — the perfect material for making hundreds of products, from chopsticks to toilet paper, cutting boards to fabric, roofing to tea. “With a little investment in growing and harvesting bamboo, you could turn a profit while helping the planet,” promises one such outfit on its website.

This enthusiasm appears to be supported by reputable science: Some of the more than 1,600 grass species in the Bambusoideae subfamily can sequester carbon both while they grow and after they’re turned into long-lived products like furniture. And they can thrive on otherwise degraded forest lands, climate impact researchers at Project Drawdown report.

But there are caveats to all of this — big ones. And you begin to get an inkling of them once you notice hardy bamboo stalks pushing up paving stones in dusty city corners where no one planted them, or tight bamboo thickets claiming roadsides across the Southern U.S. “I’ve seen it grow underneath interstates, then pause, then come up the other side,” said David Coyle. “I’ve seen it grow into the pipes and up into the toilet in a house. It’s incredibly aggressive and the minute you stop containing it, it’s going to grow outside its field boundaries.”

Coyle is an assistant professor of forest health and invasive species at Clemson University in South Carolina. Along with extension professionals in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, he’s been spreading the word — in his case, with impossible-to-misinterpret absolutism — about the ecological dangers of planting certain species of bamboo that are not native to the U.S., which is to say pretty much all of them. “It’s a horrible idea. It’s just a horrible, horrible idea. I just can’t think of a worse idea,” he said unequivocally.

Regions of this country are already contending with the ramifications of planted species gone invasive: kudzu’s vine-y takeover of the South, for example, and in the Northeast and Midwest, head-high phragmites grass running amok. Along with Paulownia trees (which have conquered parts of the Pacific Northwest and the Eastern seaboard), they’ve displaced countless native plant species, abolished habitat and food resources for wildlife, and proved all but impossible to eradicate.

“It’s just a horrible, horrible idea. I just can’t think of a worse idea.”

Coyle and colleagues say some types of bamboo could represent the same danger — in fact, one species is already spreading from Texas to Florida and up into Kentucky and Virginia. “From an ecological standpoint, it essentially creates a dead zone. If you’ve ever been in a patch of bamboo … not even birds go in there,” Coyle said. Bamboo species that are of the greatest concern are “running” bamboos, whose underground rhizomes can spread far from the original plant.

The researchers warn that for U.S. farmers, bamboo’s invasive potential is not its only drawback. They point out that there’s virtually no infrastructure here to process bamboo or turn it into products — aside from the relatively simple operation of harvesting shoots for consumption. U.S. enthusiasts crow about the $60 billion international bamboo market and its projected growth to almost $100 billion by 2031.

But that market and pretty much everything to support it is dominated by China, where many commercial bamboo varieties are endemic and therefore ecologically appropriate, said Lucy Binfield, a PhD candidate researching bamboo forestry at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “There’s already this relatively cheap and abundant source of bamboo in China, so you’re competing directly with this other huge market that’s [been] established … since the late ‘70s.”

China has also built plenty of processing and manufacturing infrastructure close to its almost 7 million hectares worth of bamboo plantations. After preliminary processing, where it may be treated with a borax solution to remove sugars and harden it, the material gets diverted into “different value chains for different products,” Binfield said. “There’s machines that will cut your bamboo culm into lots of little strips, there’s machines which will cut it in half and then flatten it, there’s machines which will chop it up.”

Almost none of this exists in the U.S., but that hasn’t prevented companies eager to tap into the lucrative bamboo market from making big promises to American farmers. OnlyMoso reportedly sells three species of bamboo to farmers; two of them are “running” Phyllostachys species predicted to have a high risk of invasiveness in North America while one is “clumping” Dendrocalmus asper, whose invasive risk potential here requires further evaluation.

There’s virtually no infrastructure in the U.S to process bamboo or turn it into products.

Cedric Coley, a businessman affiliated with OnlyMoso in Alabama, said that the company will sell bamboo seedlings to farmers for $10,800 per acre and might buy a harvest back for upwards of $22,000 per acre — although he couldn’t say whether the harvest was processed then manufactured in the U.S. or sold to companies overseas; what products it was made into; or how many farmers in Alabama or elsewhere had signed on for this service. (OnlyMoso did not respond to a request for comment and confirmation of these details.) The company has been sued at least once, by a company in Louisiana that alleges that OnlyMoso knowingly sold them bamboo that is not suitable for cultivation in that state.

“We actually tried to call one of those outfits … and they were not very forthcoming with their information,” Coyle said. “But what we got was basically, when you sign on to grow the stuff, all of the risk and work is transferred to the grower and the company assumes nothing risk-wise.”

Deah Lieurance is an extension scientist in the agronomy department at the University of Florida who’s conducted and published risk assessments of bamboo. OnlyMoso’s return-on-investment estimates are “not realistic,” she said. Not only that but many extension specialists who might knowledgeably advise farmers about other crops “aren’t educated in invasion science or invasive species management [and] they wouldn’t know the risks,” she said.

Bamboo companies are currently trying to convince Florida citrus farmers to come aboard. That’s because the state’s orange, lemon, grapefruit, and lime groves have been under a 20-year siege from huanglongbing, or citrus greening disease, for which there is no cure once a tree is infected. Radio station WLRN reported that the 2022-23 growing season — which was also impacted by hurricane damage — will yield only 16.1 million boxes of Florida oranges. That’s down from 240 million boxes in 2003-04, leaving growers desperate for longterm replacement crops. With invasive-species permits necessary to grow more than 2 acres of bamboo in Florida, however, this is unlikely to be a salvation crop for the citrus industry; Connecticut and at least one county in Virginia also have restrictions on bamboo planting, and many other municipalities and states have considered similar actions.

In South Carolina and other southerly states, Coyle said bamboo was being pushed as a replacement for pine plantations, which produce trees for timber. In some instances, these plantations are plagued by a type of bark beetle called the Southern pine beetle, which kills trees when it tunnels into their tissue, disrupting their flows of nutrients. Still, this pest can be controlled with good management, Coyle said, leaving intact a plantation. Then — unlike a bamboo stand — it can generate additional income via livestock grazing through it, interplantings of fruit trees, or “a lot of people just manage their stands for hunting. The only thing I’ve seen people do with bamboo is figure out how to get rid of it because once it takes over a spot, that land is essentially useless.”