In which we contemplate what it will take to get Americans to love this surprisingly unpopular sour vegetable.

Fifteen of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s federally funded gene banks are common-sensical repositories, housing plants that thrive in the regions where they’re located: bananas in Puerto Rico, onions in Geneva, New York. But the 16th bank, the Western Regional Plant Introduction Center in Pullman, Washington, is weird no matter how you slice it. Like its brethren, its 14,000 seed and rootstock accessions, representing 1,300 species, are meant to safeguard agriculture’s genetic diversity and are available to breeders and commercial growers.

But Pullman’s are mainly plants that “didn’t fit into anybody’s else’s collection,” said curator Alex Cornwall. Its orphaned odds and ends include sugar and table beets; legumes like Lupini beans and lotus; cool season grasses; dye plants like madder root and bed straw; dandelions being investigated for their potential to make natural rubber; and culinary rhubarb — 47 varieties in all, with 10 more on the way, including some crop wild relatives.

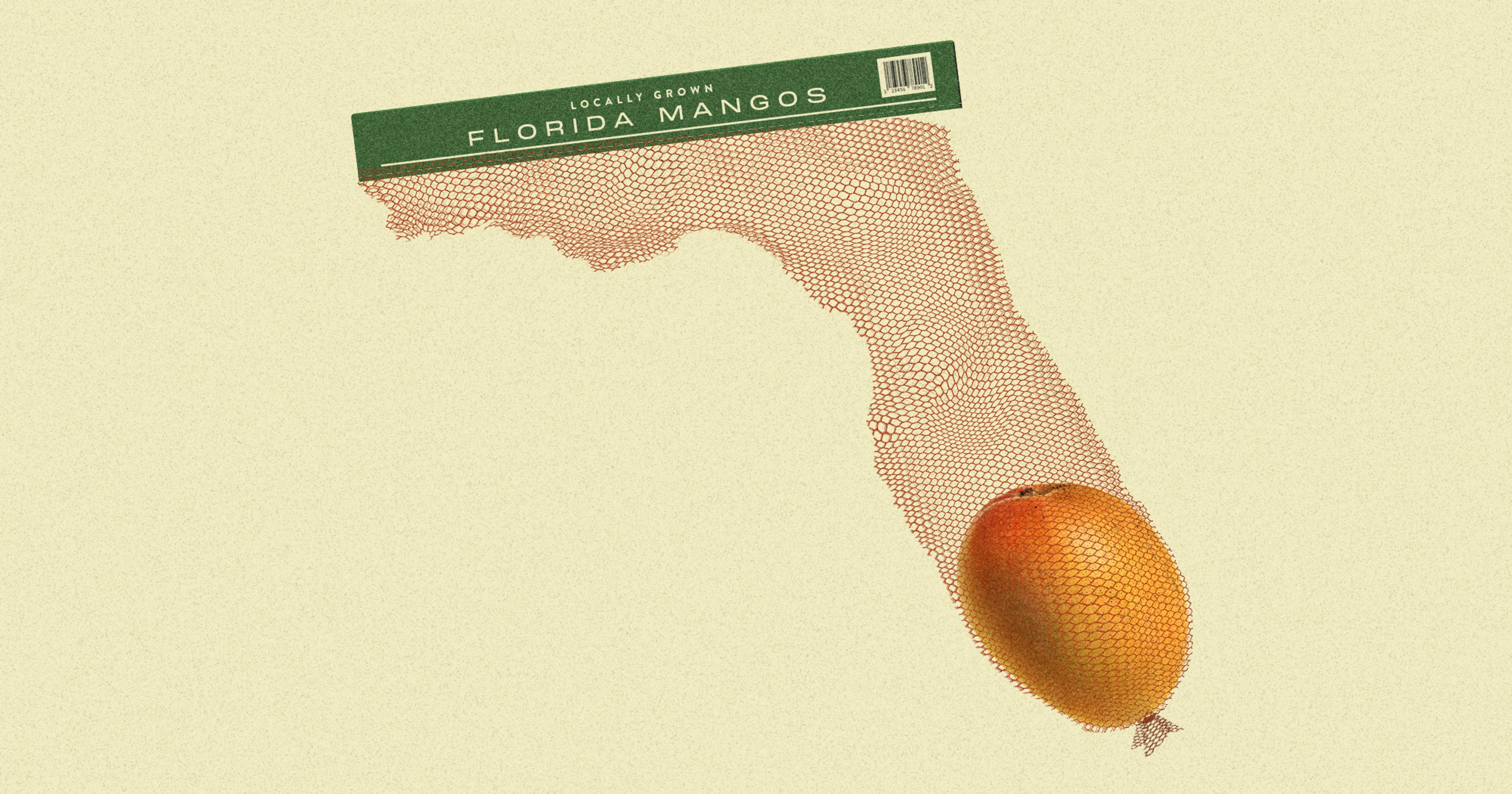

Despite the fact that rhubarb’s pinkish/greenish stalks can reliably be found piled up on farmer’s market tables pretty much everywhere starting in April, it’s not much of a farm staple outside the Pacific Northwest — possibly because it flourishes in plenty of American home gardens. A handful of holdouts in Washington’s Puyallup Valley still grow rhubarb both in its field and forced form (more about that later). But in 2022, only 1,720 acres of rhubarb were farmed across the country; for comparison, the crops that bookend rhubarb in the Census of Agriculture totaled 20,400 acres that same year (radishes) and 79,400 acres (spinach).

You can intuit near-desperation in Cornwall’s voice as he discusses the professional disinterest in this vegetable that’s related to buckwheat and loves temperatures as cold as minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit: If professional growers “request rhubarb from me, I am 100 percent willing to send material to them” — for free, no less — “so that we can get more of these varieties out there,” he said. Takers in 2024: three, including a group from Canada that was discounted because they neglected to secure the necessary import permit. Consider this a rhubarb stan article as we consider: What would it take to get American farmers and eaters to embrace the Rheum?

***

Perhaps the answer can be found in northern England’s Yorkshire Triangle. This is the accidental birthplace of forced rhubarb, a winter crop that’s grown in total darkness after being transplanted from field to hothouse (or as became traditional in Yorkshire starting 200 years ago, a shed heated by the region’s abundant coal supply).

Legend has it that a gardener unwittingly kicked a bucket over a rhubarb plant, only to discover that it thrived in the murk. In a few short weeks it had used the energy stored in its roots to shoot up dramatically. Its normally pallid, super-sour stalks were colored a vivid pink and tasted sweet(er), with less of a stringy, tough chew; the stalks were capped with pale (toxic) leaves wrinkled like Napa cabbage. Even now, starting in January enthralled Brits flock to Yorkshire, where the delicacy is harvested by candlelight after a growing period so fast and intense — allegedly an inch per day, as it frantically seeks sunlight — the plant makes a high-pitched popping sound.

“There’s not a whole lot of research being conducted, and I think part of it is the perception that rhubarb is only seen as a dessert.”

Brian Anderson runs Knutson Farms in Sumner, Washington, which sells over a million pounds of Crimson red and Johnson red rhubarb a year; the farm started forcing rhubarb in the 1940s, to keep the crew busy over the winter. The plants can live for decades but working them is labor-intensive. To keep them healthy as they age, Cornwall said the plants actually need to be chopped up occasionally; some farms’ crews will run a tractor or a spader through a field of them — or chop them one by one with a shovel — so the centers of their crowns don’t rot. Like apples, rhubarb doesn’t breed true if it’s raised from seed, so chopping it up into pieces is also how you make more plants to propagate.

Only well-established field plants that are three or more years old are hardy enough to be forced as the days grow short and cold. As soon as they go dormant, in late December, “We dig them up, put them in tight rows in our completely dark hothouse. And they just grow,” said Anderson. Any plants that survive the intense effort of transferring all their energy into their shoots get moved back to the field come spring. “If we get 60 percent of that [winter] crop, we’re pretty happy,” Anderson said. He manages to sell everything he harvests, to local grocers as well as mail-order chefs and mixologists interested in turning out cobblers and cordials. But as he told Washington’s Capital Press, he doesn’t see much potential to grow his rhubarb business; any more and “we probably wouldn’t have a sale for it,” he said.

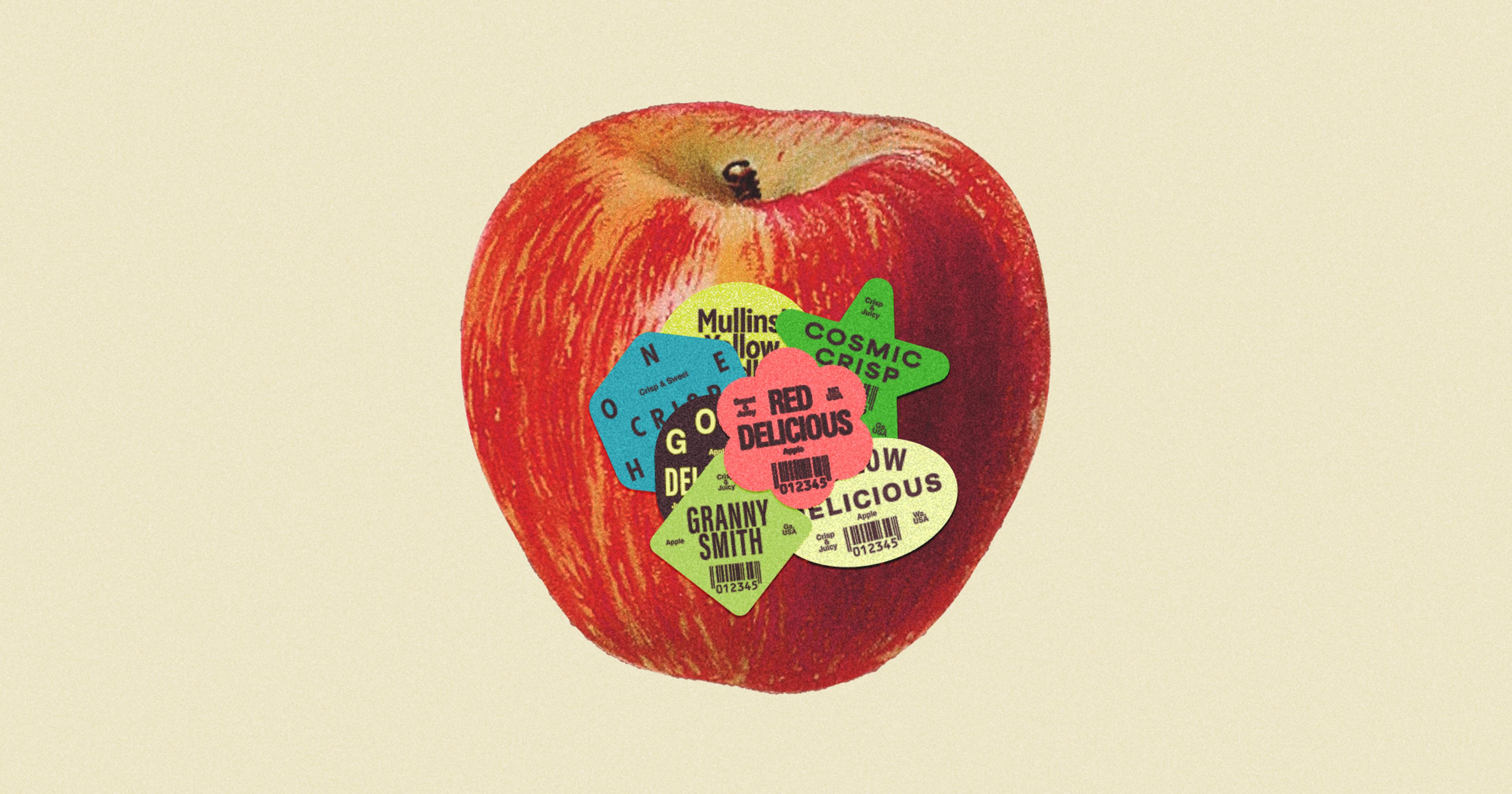

USDA’s Cornwall thinks part of the problem is rhubarb’s association with sweets. “There’s not a whole lot of research being conducted, and I think part of it is the perception that rhubarb is only seen as a dessert,” sweetened with sugar and other, less astringent, fruits. It wasn’t always, or everywhere, so.

The U.S. got its initial predilection for rhubarb from the U.K., where it didn’t start appearing in cookbooks until the early 19th century, when sugar became affordable to the masses. Before that, it was used medicinally, as a purgative to restore “the tone of the stomach,” according to a manual published by an 18th century British physician. Centuries earlier, as rhubarb traveled along the Silk Route from China and Tibet, whence it originated, it was heralded as a cure-all for spleen and liver ailments; inflamed kidneys; sciatica; asthma; dysentery; fever; and poisonous animal bites.

In the late 1800s, the USDA moved its rhubarb collection to a new gene bank in Palmer, Alaska, as a means to bolster the fresh food supply for people who’d settled in with the Klondike Gold Rush (they’d brought cold-loving rhubarb with them); starvation was a major concern. By then, eating the plant, which is rich in vitamin C, was also known to be a reliable way to stave off scurvy; the leaves are inedible, however, due to their high oxalic content. As a bonus, frigid winters and long summer days meant an Alaskan homesteader could raise a rhubarb the size of a shed. Today it’s recognized for its anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, digestion-promoting properties.

“My technicians sample rhubarb [varieties] growing in the field; they eat it like celery and they’ve become connoisseurs.”

What other important abilities might rhubarb possess? “We’re preserving these plants in the hopes that people are going to come looking for them,” Cornwall said wistfully. He and his team have even identified types that can withstand increasing heat from climate change. “We’ve got a farm down the Snake River where it gets well over 100 degrees during the summer and [several] accessions are thriving,” he said. Southwestern desert rhubarb? Anyone?

Fed up with waiting for his worthy collection to be discovered, Cornwall decided to take matters into his own hands. At the end of May 2025 he hosted a Rhubarb Rumble in the town of Pullman. Locals were asked to submit dishes, — especially non-desserts. Cornwall made chutney, although he’d been intrigued by tales of an Alaskan rhubarb competition to which someone contributed a rhubarb pizza. (Pork barbecue in tomato/rhubarb sauce was on the menu but the winner was a rhubarb panatela.)

In fact, outside the Anglo-Saxon tradition of pies and jams lies a whole swath of cuisines that use rhubarb as a savory ingredient. Tugum rawash is a rhubarb sauce topped with coddled eggs — a sort of Afghani version of Middle Eastern shakshuka. A Persian stew called Koresh Rivas tempers bitter rhubarb slices with lamb and spices. TikTok is replete with videos of gourmets munching on fresh rhubarb stalks either with a sprinkle of salt or au naturel.

“My technicians sample rhubarb [varieties] growing in the field; they eat it like celery and they’ve become connoisseurs,” Cornwall said. All he wants to know is what he can say or do to convince you to become a connoisseur, too.