In making the case for a tree crop revolution, food writer Elspeth Hay also challenges readers to rethink humanity’s place in the cycles of nature.

On the hottest of July afternoons, as I wrestle my lawnmower through the soup-thick humidity and Amazonian undergrowth of a North Carolina summer, I wipe the stinging, salty sweat from my eyes and imagine that I am in hell.

Ancient Greek hell, specifically — I identify with Sisyphus. The lawnmower is my boulder, and the growing grass forever keeps me from pushing it to the summit of a tidy yard.

Elspeth Hay, food writer and creator of Massachusetts public radio program The Local Food Report, believes American agriculture is trapped in a similarly Sisyphean cycle of plowing and planting annual crops. In her just-released debut book Feed Us with Trees: Nuts and the Future of Food, she suggests that a better path may lie with perennial nut trees like oaks, hazelnuts, and hickories.

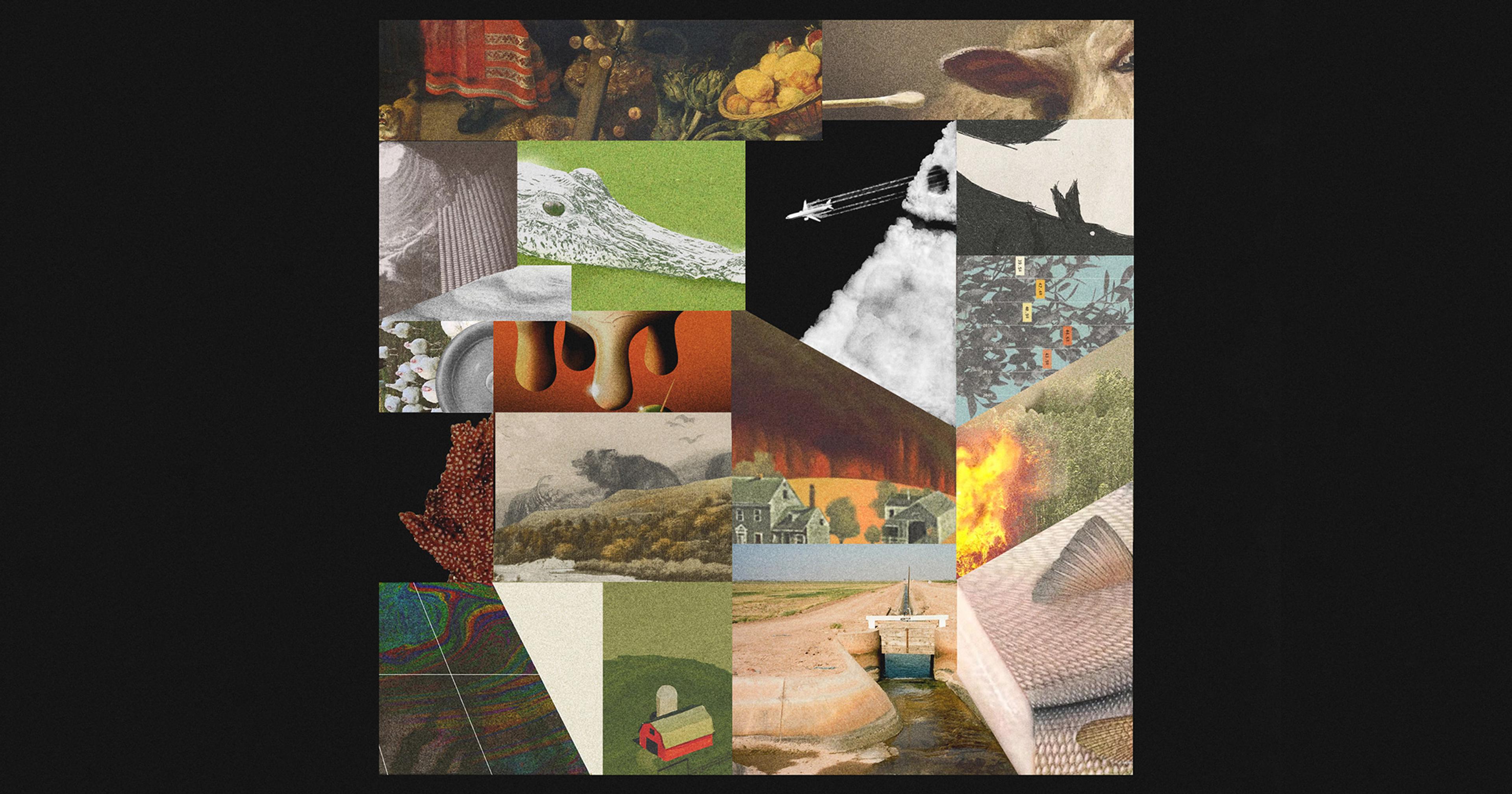

The country’s reliance on industrialized monoculture field crops like corn and soy, Hay argues, has led to environmental issues such as soil erosion and an unhealthy food culture, heavy on refined grains. Through exploring the agronomy, cultural history, and nutrition of nut crops, she proposes a different story of how people can partner with plants for a world of ecological abundance and human wellness.

The book plays out like a tale of religious conversion. Hay summarizes her original faith with the phrase “No Farms, No Food,” a simple dogma that she unspools into a creed of unspoken assumptions about humanity and its relationship with the Earth. Going back to the Biblical creation narrative, in which Adam and Eve are expelled from a naturally productive garden to earn their bread by toil, Hay believes people in the West have grown alienated from their environment.

“We seemed to be the only species without a habitat; the only species without wild, abundant foods; the only species destroying our home planet and the vibrant communities of life that cover it,” she writes. According to this mythos, humans can flourish only at the expense of other creatures, by converting ever-larger portions of the world to farmland and staving off nature’s encroachment each year to plant high-performing annuals.

Hay’s road-to-Damascus moment takes place on a trip to Northern California, where she meets the Indigenous activist and cultural biologist Ron Reed. In a travelogue rich with visual detail — I particularly enjoy Hay’s fine eye for the traces humanity leaves upon landscapes, from grapevines to graffiti — the author visits the ancestral home of Reed’s Karuk people along the Klamath River.

In the valley the Karuk believe to be the center of the universe, Reed explains how his culture traditionally lived off the land, by stewarding oak forests with intentional burns to encourage the production of acorns. Their mythology treats humans not as despoilers of nature, but as vital components, carefully using fire to support habitat both for themselves and for animals like salmon, deer, and elk. Through this Indigenous example, Hay becomes obsessed with the potential of perennial nuts as a superior replacement for annual grains.

“Listening to Reed was like walking into a world I had always hoped might exist but never really believed in. I had no reference points for humans as ecologically good; I’d never heard us described this way,” Hay recalls. “In Reed’s stories, we had a habitat. We had responsibilities toward other species. And we had an environmental niche.”

“I had no reference points for humans as ecologically good; I’d never heard us described this way.”

The essential arc here, of Indigenous lifeways offering a revolutionary perspective shift for modern civilization, reminds me of David Graeber and David Wengrow’s monumental The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. That 2021 book, a New York Times bestseller, drew heavily on historical critiques by Native commenters about what they saw as the strange and harmful ways of European settlers. Hay cites the historians in her acknowledgements, and while her book is more narrowly focused than their sprawling tome, it’s no less ambitious in its aim to interrogate a founding assumption of Western culture.

Having sown this proverbial acorn of a narrative, Hay spends much of the text defending it from the obvious counterarguments while it grows into a mighty oak. She deftly addresses questions about nuts’ yield, management by fire, and culinary potential, tying each chapter of well-supported research together with a scenic vignette from her reporting trips.

As a resident of the Blue Ridge Mountains who’s previously reported on a nut collective in Asheville, I was especially taken by Hay’s descriptions of Appalachia. Through archival documents and lively interviews, she reconstructs the thriving nut-based economy that carried on in the mountains through the early 20th century, until a fungal blight wiped out the American chestnut.

That section and others emphasize how both Indigenous and historical Western cultures reliant on tree nuts have held different ideas about land, embracing ideas of the commons and shared foraging rights rather than considering every parcel its owner’s exclusive domain. In Appalachia, for example, residents had legal permission to gather nuts and feed animals in the woods beyond farmers’ fences.

It’s enough to make a man walk away from the lawnmower and plant an acorn.

“All the spending money [many mountaineers] had came from nuts they had gathered on other people’s land,” Hay writes. “This was a completely different picture than I’d understood before, a way of life based on a set of cultural agreements I’d never heard of or experienced.”

The U.S. would be better off, Feed Us with Trees claims, if it restored some of those agreements and the tree crops that go with them. Compared with annual grain fields, nut forests build soil fertility over time; they serve as habitat for many more species; and they invite more intimate connection between people and place.

And as humanity wrestles with the climate change it’s causing, argues Hay, nuts and their management offer a powerful new mythology for how to relate to the Earth. “We don’t just need to move away from No Farms, No Food; we need a story to move toward: a new collective mission, a freshly forged communal understanding of how we might do our jobs in this world where we are a keystone species,” she writes at the book’s conclusion.

It’s enough to make a man walk away from the lawnmower and plant an acorn.