There’s a large movement afoot, using agricultural land for solar developments. For some rural neighbors, the cons outweigh the pros.

This essay is from our Perspective section. The opinions presented do not represent those of Offrange or Ambrook, its parent company.

Many farmers view putting solar panels on their land as a decision with only net positives. There is significantly less labor in renting land to an energy company than planting and harvesting a crop; you’re helping create clean energy; and, best of all, when the lease ends, the land is returned to the farmers’ use. For many aging Wisconsin farmers, of which there are many— the state average is 56.7 years old — leasing land to an energy company allows them to keep their land and reduce the labor required to make a living.

But when large-scale utility developments — whether they are solar, wind, or power infrastructure — try to build in rural areas, neighbors often push back. Though it’s easy to brush this off as base NIMBYism, there can be legitimate concerns about solar projects from rural neighbors.

My dairy farming friends Gary Swain and his wife, Dana, have learned firsthand how large-scale solar developments could possibly impact their farm and their neighbors. They’ve also discovered how little they can do to stop it.

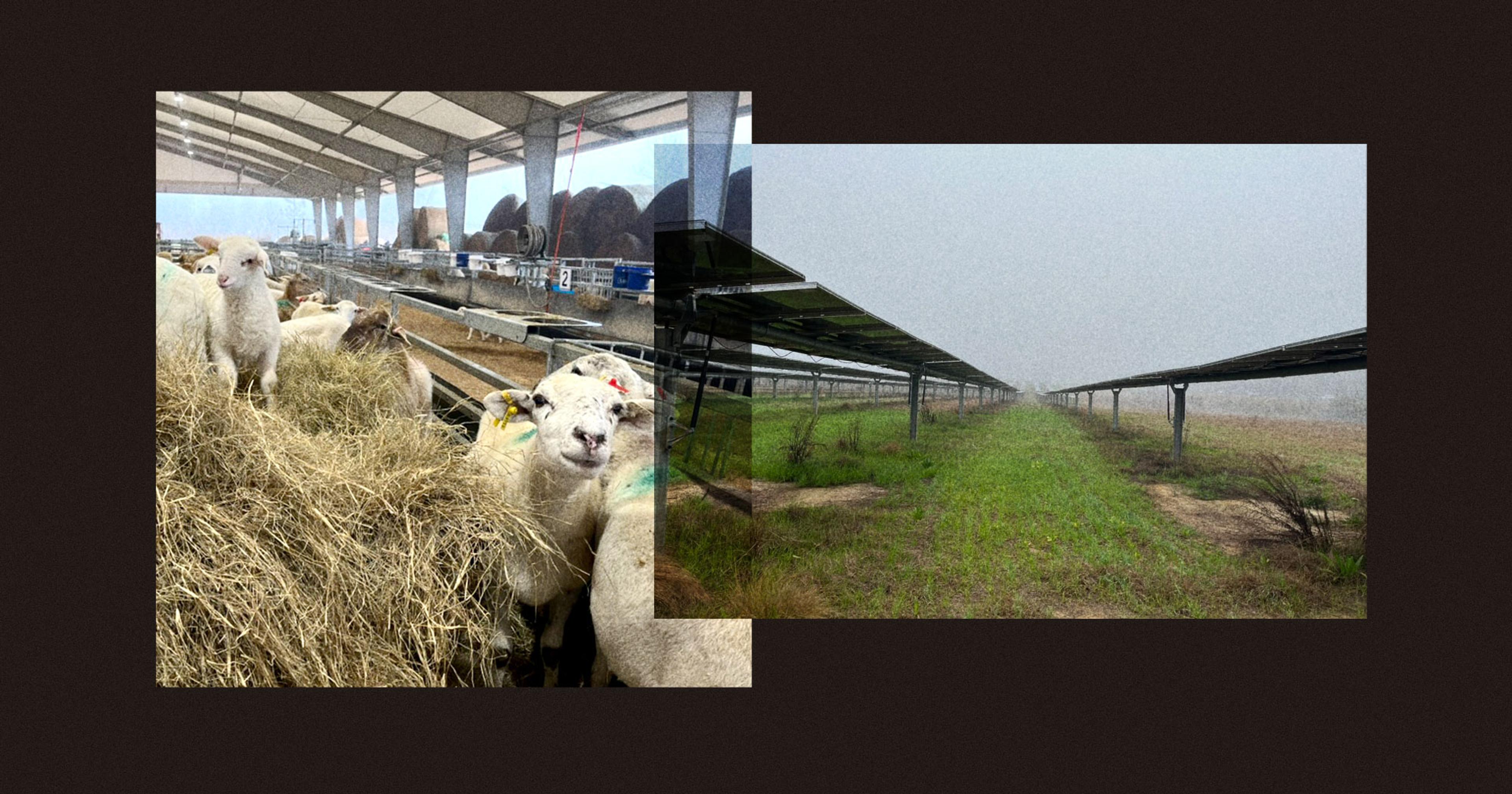

Three years ago a solar company proposed a roughly 4,600-acre solar development in the Wisconsin township where Gary, Dana, and their family farm. Both of them grew up on dairy farms and showed their livestock in 4-H (where I met them). They also both have off-farm jobs — a necessity for most people who work in ag. Gary milks about 30 cows with his brother; they have roughly 60 young stock on the farm. In addition to their livestock, they grow the alfalfa and corn used to feed them — their families have been farming continuously in the township for 180 years.

The proposed development near their property has leased 4,600 acres of farmland for a 2,400-acre solar array in the towns of Christiana and Deerfield. The project would generate 300 megawatts of solar, enough to power 90,000 homes and provide 165 megawatts of battery storage; it would be the largest solar project in Wisconsin. Gary and Dana, along with their neighbors, were surprised to learn that the process for approving or denying a development like this doesn’t reside in local decisions made by town boards. The Wisconsin Public Service Commission (PSC) decided how much weight to give the viewpoints of neighbors impacted by large utility developments.

Gary, Dana, and their neighbors have concerns about this large of a solar development being built around their farms, homes, and a school. Gary is concerned about stray voltage from the energy transmission and large energy storage batteries affecting his cows and their milk production, as noted in this Wisconsin Public Radio article. There are additional worries about wildlife being impacted — will large numbers of deer, turkeys, and other wildlife move their routes to go through other farmer’s fields if they can’t access the typical paths now blocked by the solar array?

Gary and Dana requested an agricultural impact study to quantify these effects, but both the PSC and the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection declined to conduct one. Is there enough known about the effects of solar panels on the soil and groundwater? What about the risk of fire from the large batteries storing energy? How will local roads hold up under heavy truck traffic for the building of a roughly 3,400-acre solar development?

The uncertain answers to these questions highlight a lack of research into the effects of large solar developments, especially on prime agricultural land in the Midwest. Most large-scale solar projects in the U.S. are in the West, on arid land that is unsuitable for farming. This limits the applicability of these studies — such as this or this — to the temperate Midwest. The lack of applicable research regarding the effects of large solar development on Midwestern wildlife is noted in the PSC’s environmental assessment of the project.

Nationally, opposition to large-scale solar development from farmers and rural neighbors has been growing and becoming organized.

What research there is presents a mixed bag on the effects of solar developments on the environment. On one hand, there are confirmed negative effects on certain species of wildlife, such as aquatic habitat birds (ducks, geese, loons, etc.) that confuse reflective solar panels for water and try to land and collide with the solar panels. Research is being done by the United States Geological Survey into this phenomena, called the Lake Effect Hypothesis.

Research from Murdoch University found that large solar developments can attract insects, which create new feeding areas for birds and bats. However, this can cause birds and bats to fly off course as the solar panels mimic large bodies of water, as well as increase the risk of collisions. Additionally, migratory species may find their typical routes blocked, which disrupts nesting and feeding patterns. Although some negative impacts to wildlife can be mitigated by wildlife-friendly design, such as one in Nevada which preserved native plants and left openings in fences, implementing these measures is rare.

Results are also mixed for pollinators. One study found that the building of solar developments may contribute to pollinator loss because of vegetation removal. Another study found that establishing pollinator-friendly habitats in solar developments may result in positive effects such as increasing flower diversity, pollinator abundance, and diversity. Many of these studies emphasize that more research is required to fully understand the relationship between solar energy infrastructure and wildlife. This is a key point for resistant rural communities — we don’t yet know enough about the consequences to approve these massive solar projects.

Soil degradation can also be a problem for large-scale solar, in the form of erosion when solar companies do not mitigate this risk. This is evidenced by a $135.5 million settlement for damages caused by erosion and lack of sediment control after clearing and grading 1,000 acres of timber and farmland near a Georgia landowner’s property. And although the heavy metals used in solar panel infrastructure are said to be safe and pose no significant threat to soil quality, a study in 2021 found that ongoing monitoring is required to ensure this.

Here in Wisconsin, local news coverage has presented the project’s positives and glossed over the concerns of neighbors as NIMBYism. Wisconsin Public Radio quotes Michael Vickerman, policy director of RENEW Wisconsin, a non-profit environmental organization: “This lawsuit is the result of a couple of individuals and Town of Christiana government that just don’t like solar on agricultural land. That’s all it comes down to.” Vickerman added that large solar farms are operating in Wisconsin without causing any environmental damage (an unverified claim).

“This is good land that has grown crops for hundreds of years. Why do they need to put it here?”

Like several large-scale utility projects in Wisconsin, this development is being appealed in circuit court. The townships of Christiana and Deerfield are suing the PSC to stop the project, citing the land leases by the private utility exceeding the 15-year term of leases spelled out in Wisconsin’s Constitution.

Nationally, opposition to large-scale solar development from farmers and rural neighbors has been growing and becoming organized. A non-profit formed in 2018, Citizens for Responsible Solar, helps rural communities in fighting large-scale solar development on agricultural or forestry-zoned land. In the Catskill region of New York, for instance, opponents purchased 60 acres of a proposed solar development in an effort to stop the 267-acre solar project.

In Southwest Colorado, residents have organized and had success in opposing a solar development located on an important cultural landmark, Wright’s Mesa, through establishing local regulations. A current bill in the Wisconsin legislature would require similar local approval of major solar or wind projects before the PSC can decide on them.

Gary and Dana can find common cause with ranchers in Colorado, all asking questions about putting solar on farmland. Said Dana, “This is good land that has grown crops for hundreds of years. Why do they need to put it here?”

At this point, though, her question might be moot. In the town of Christiana, construction has already started on the solar array, with semis hauling large excavators following local tractors and grain carts as they bring in this year’s harvest.