New research highlights the steadily increasing scarcity of food animal vets — and what that could mean for our supply chain and the rural economy.

Over the last few years, shoring up our supply chain has been the subject of much concern, conversation, and federal investment — especially when it comes to the food supply. But one particular link in that chain, arguably one of the most vital, has managed to escape much scrutiny: There is a woefully scarce number of veterinarians to care for food animals in rural America.

“We have counties in Mississippi that don’t even have a large animal veterinarian, and that’s really what we’re hearing across the entire country,” said Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith (R-MS) at a press conference earlier in the week. “Our nation’s food security and economic security are put at risk without sufficient veterinary oversight to ensure the health of animals in the food supply chain.”

Hyde-Smith was keynote speaker at the unveiling of a comprehensive new report titled Addressing the Persistent Shortage of Food Animal Veterinarians, prepared by Clinton Neill of Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. In the report, Neill starkly details the core shortage, what led to it, and the startling effects it can have on America’s food supply

“This is not a new problem,” said Neill, who has spent years on this line of research. “What is changing is the sense of urgency. It’s something that’s going to affect the long-term ability to have a really robust food safety system in the U.S. Because veterinarians, especially food animal veterinarians, play a vital role along the entire food chain.”

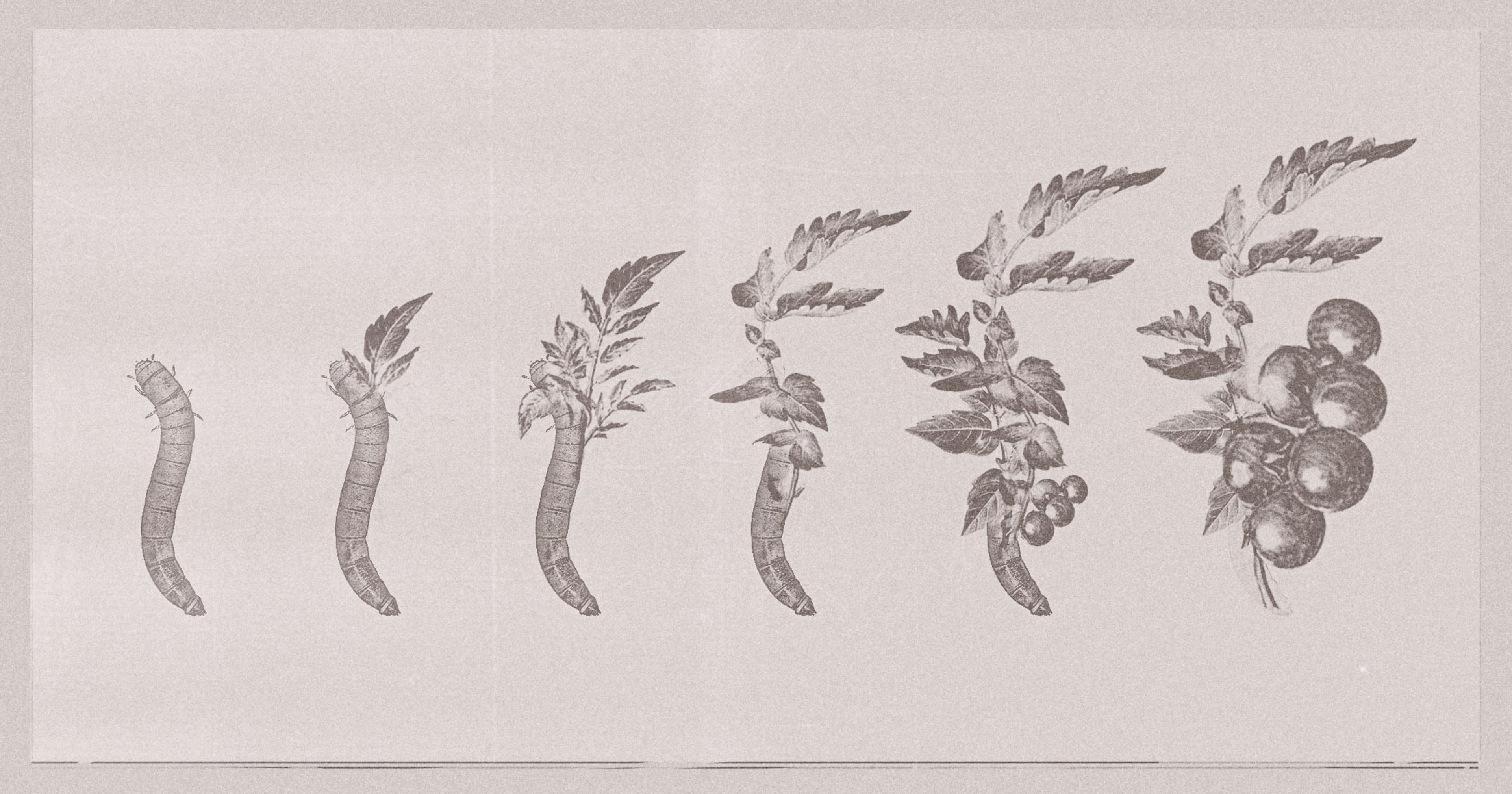

Forty years ago, food animal veterinarians were the largest single category in the profession, with a full 40% of practitioners focused on livestock. But a confluence of factors, including a persistently steady increase in the need for pet medical care — as well as the promise of higher income from that sector — has led to a precipitous dropoff over the years.

“Finding someone who wants to live in the middle of nowhere and have such a demanding schedule is hard.”

Food animal vets are now only 5% of a profession currently suffering from low overall numbers — a percentage that Neill predicts will keep decreasing as older practitioners retire. Of the thousands of veterinary school graduates each year, only 3-4% are choosing a food animal-focused practice. Neill said it can be a hard sell, convincing a young vet to set up shop in our nation’s rural areas, where the vast majority of food animals are raised.

It’s certainly not the only profession to suffer from the urban/rural brain drain of highly educated professionals, but the impacts on food production and rural livelihoods are acutely felt.

“Out here in western Kansas, there isn’t much around, and vets are hard to come by,” food animal veterinarian Kacey McDaniel told Successful Farming in 2019. “Finding someone who wants to live in the middle of nowhere and have such a demanding schedule is hard.”

“The reality is that veterinarians who do that kind of work don’t get the same salaries as vets in metropolitan areas, and the call structure is not appealing,” added Kansas vet Chase Reed, echoing another finding from the report. “I’m on call 180 days a year, any hour of the day or night. It takes a special person to come out here and persist in this style of practice.”

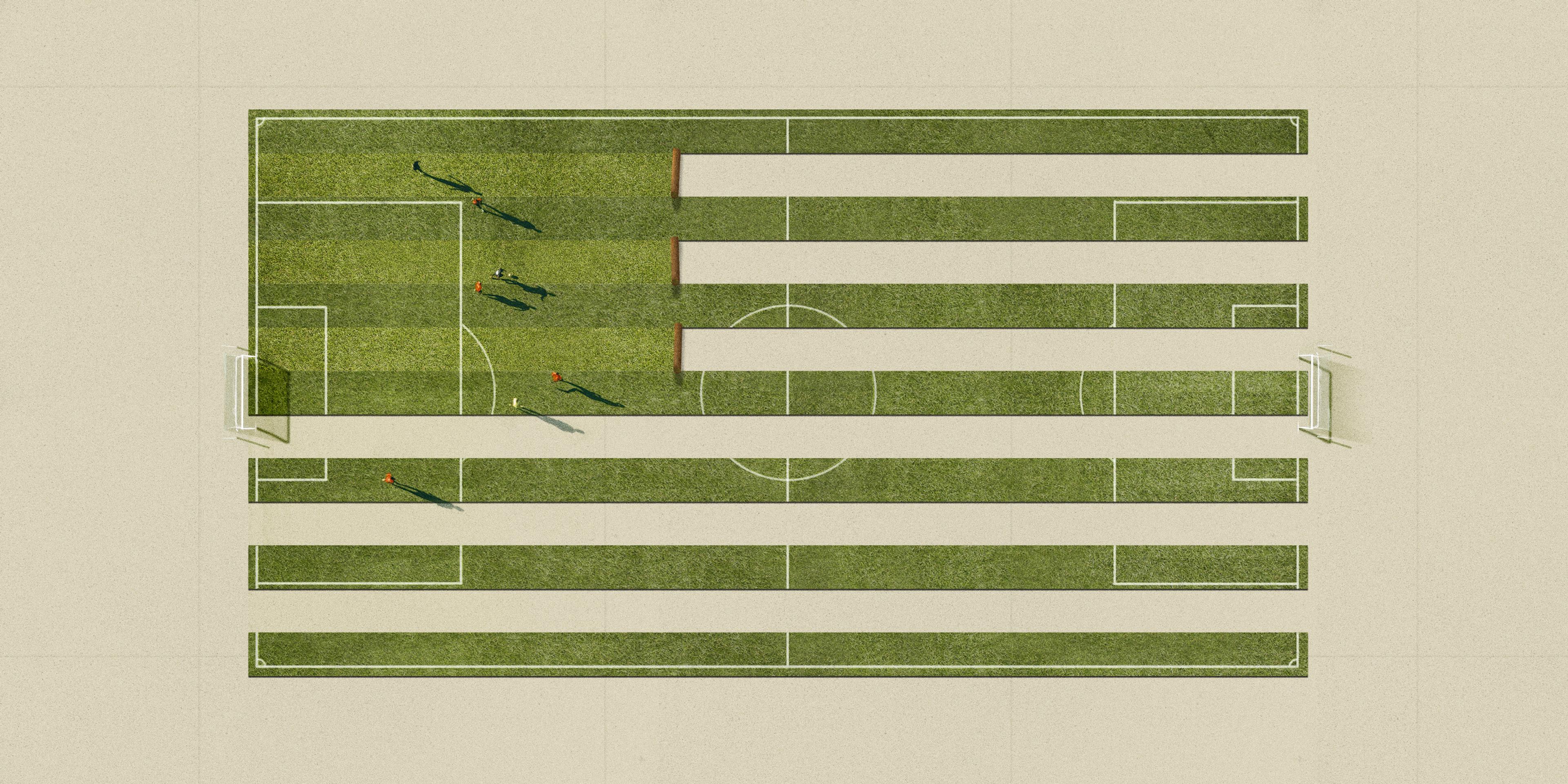

In 2020, only 11.7% of veterinary businesses were in counties with 20,000 people or less, while in counties with populations less than 2,500, this number was a mere 2.3%. With so few vets in certain regions, it’s not uncommon to spend many hours on the road for each farm visit. Neill’s report details the challenges to rural economic growth this situation poses, as well as the potential impact on both food security and food safety.

With so few vets in certain regions, it’s not uncommon to spend many hours on the road for each farm visit.

“This shortage can lead to dire consequences at the producer level,” said Stephanie Mercier, senior policy advisor at the Farm Journal Foundation, which commissioned Neill’s study. “If a farmer has to wait several hours for a vet to be able to show up and look at an animal, it raises the risk that not only will that animal get sicker and die, but also potentially infect the rest of the population.”

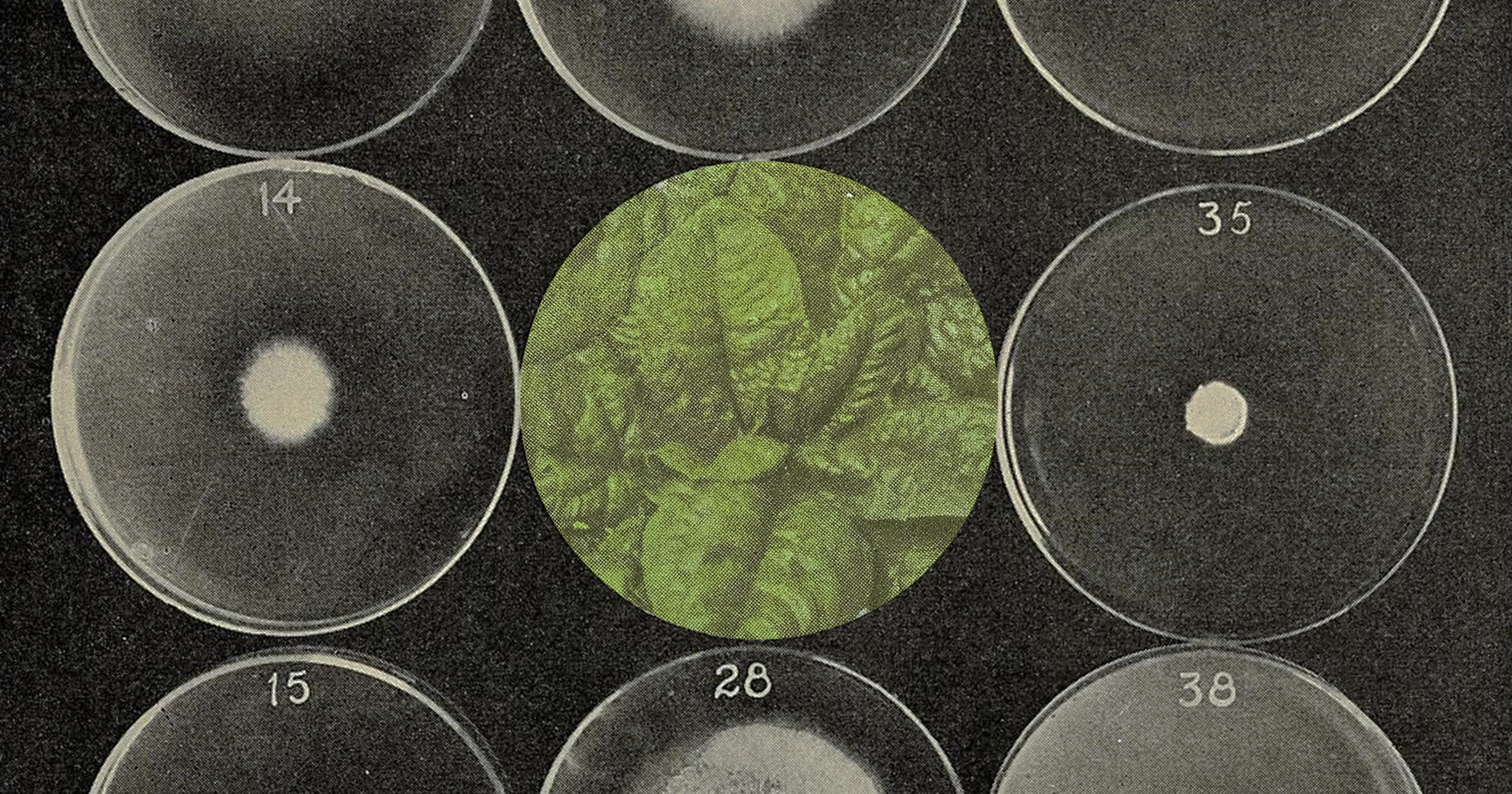

Take, for example, the deadly avian flu, a recent strain of which appears to now be affecting mammals. Rural vets are on the frontlines of detection and outbreak prevention; when a disease this destructive can spread so quickly, it’s not hard to imagine what happens with a lack of trained professionals on hand. This same argument could apply to African swine fever, salmonella, and all manner of infectious disease.

Mercier added that there’s a failure among politicians and the general public to connect the dots between, say, rising meat prices and the lack of food animal vets. Her organization is currently working to educate more members of Congress about the stakes of the issue, starting with Hyde-Smith, whose daughter is in veterinary school.

Neill’s report isn’t all gloom and doom. He lays out a multi-tiered plan for increasing numbers of food animal veterinarians, much of it focused on financial incentives. This could include the federal government improving its loan forgiveness program for rural vets, and otherwise subsidizing one of the less lucrative corners of veterinary medicine.

“What can we do at a community level to create a more welcoming environment for veterinarians to not just relocate but to stay?”

In terms of quality of life issues, Neill is less certain how to make rural living more appealing to new graduates. In particular, he sees an issue with enticing young people to build a family in areas with limited professional and social opportunities. “How do you build a system that can help with that? I’m not sure I have the answer.”

On the upside, Mercier said her organization recently put together an advisory group, composed of working veterinarians and other adjacent professionals, to help brainstorm that very issue. At their most recent meeting they analyzed the question of “What can we do at a community level to create a more welcoming environment for veterinarians to not just relocate but to stay?”

Mercier’s question may appear to be an innocuous one. But with our food security and the economic viability of rural America itself at stake, it appears to be in urgent need of an answer.

Mercier continued, “It’s not just whether we can provide some financial assistance to acquire the equipment and the technology [a veterinarian] needs to run his office, but how can we help improve the social environment? If that veterinarian is married, can we help their spouse find a job? It’s not an easy problem to tackle.”

Ed. Note: An earlier version of this story said Sen. Hyde-Smith’s daughter was a veterinarian, but she has not yet completed veterinary school.