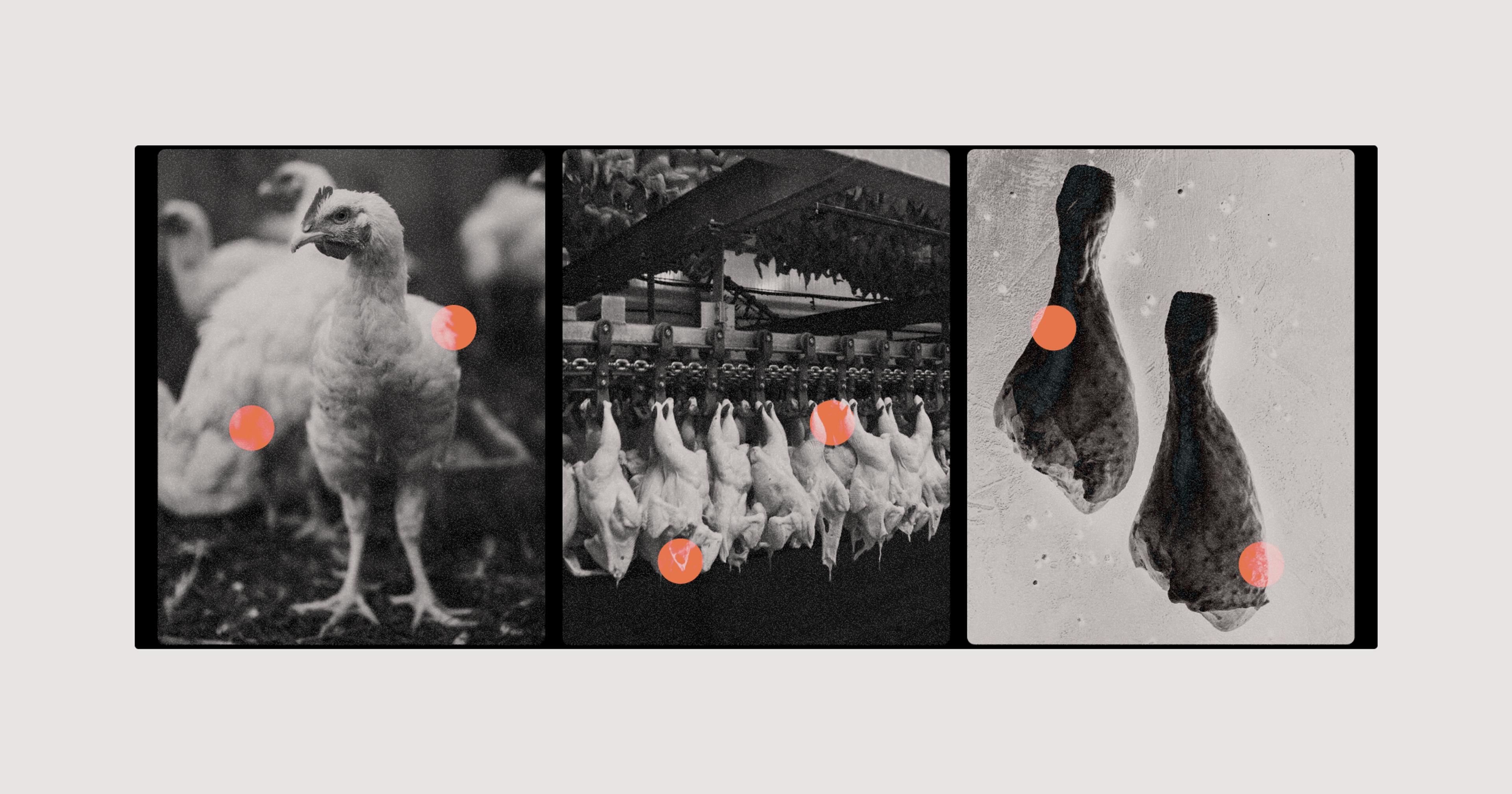

After years of inaction — and outside pressure — the agency is proposing sweeping new changes to how it handles the foodborne bacteria. It starts on the farm.

Salmonella infects roughly 1.35 million people in the U.S. each year, leading to about 26,500 hospitalizations and 420 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And for some time now, roughly one quarter of those infections have stemmed from contaminated poultry products. Just this month, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced a sweeping bloc of proposed salmonella reforms.

“Ultimately what we want to have in place is an ‘end product standard’ so we can better ensure that poultry products contaminated with salmonella — either at the levels or the particular serotypes that make people sick — aren’t allowed to be sold,” said Sandra Eskin, USDA’s deputy undersecretary for food safety.

But though USDA’s ultimate goals are to ensure a safer product for consumers, the proposed changes start on the farm. Eventually the agency wants poultry flocks to be tested for salmonella before reaching the slaughterhouse — a departure from current practices. “Creating an end product standard pushes everything all the way back to the farm in terms of pressure to reduce contamination,” Eskin said.

Some consumers might have assumed there were already safeguards in place to prevent infected poultry from being sold or consumed. But before these proposed changes from the USDA, there have been long-standing obstacles to putting such protections in place. Salmonella is a very common bacteria, for one, and the vast majority of its nearly 2,500 serotypes, or particular strains, are not harmful to humans. If restrictions are painted with too broad a brush, it could block sales of poultry that is perfectly safe to eat. Similarly, salmonella concentrations below a certain level are unlikely to pose any threat. In part, that’s how Eskin explained the agency’s longstanding reluctance to declare salmonella an “adulterant,” which would give much broader powers to regulate and recall contaminated poultry.

Now widely recognized as a potentially dangerous contaminant, E. coli was on the backburner for much of America’s agricultural history. That is, until 1996, after a deadly mass food poisoning incident stemming from ground beef sold at the fast food chain Jack in the Box. Public outcry led to USDA declaring E. coli serotype 0157:H7 an adulterant in ground beef, which led to the creation of a vigorous product testing regimen. Ultimately the goal was to prevent sales of any ground beef that contains traces of the pathogen.

Large poultry producers like Perdue and Tyson have come out in support of USDA’s reforms.

“It took over 90 years for USDA to modernize its beef inspection process in terms of E. coli,” said Mitzi Baum, director of the nonprofit group STOP Foodborne Illness. The proposed salmonella changes are “yet another step in that process of continually modernizing based on current science,” she added. This time, USDA’s actions aren’t the result of one jarring incident; they come from years of careful evaluation and sustained public pressure.

The agency’s proposed approach to handling salmonella features three basic prongs. It starts with mandatory flock testing before animals move “downstream,” in industry parlance. Next, it suggests greater Food Safety and Inspection Services (FSIS) monitoring during slaughter and processing. Finally, USDA is attempting to devise a final, enforceable standard for the end product — determining which salmonella serotypes, at what levels, will be declared unacceptable adulterants in raw poultry products. The agency is already taking action to declare salmonella an adulterant in breaded, stuffed, raw chicken products, the source of repeated outbreaks in recent years. Eskin said these products are merely a starting point.

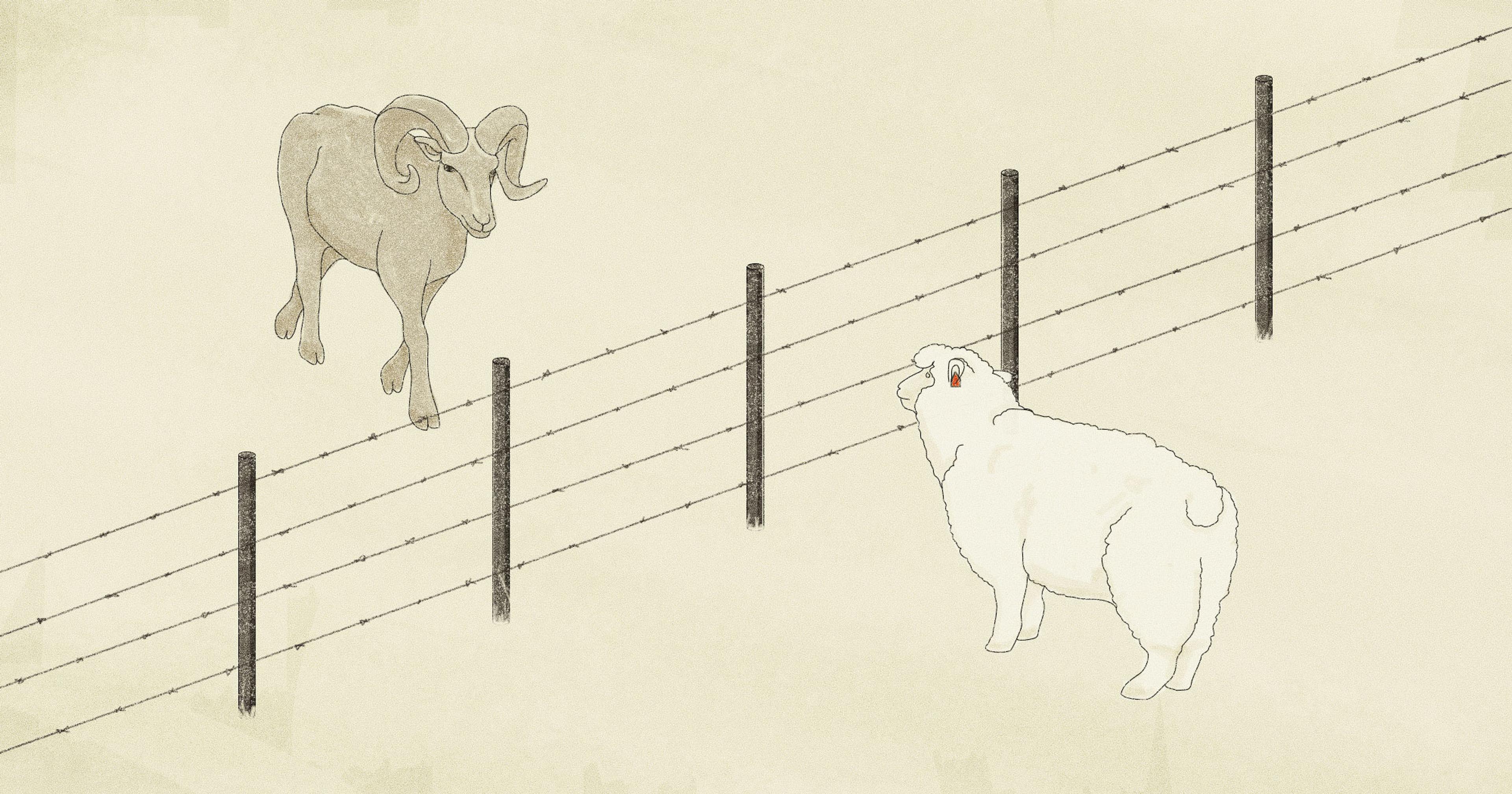

Despite a track record of not always cooperating under legal pressure, large poultry producers like Perdue and Tyson have come out in support of USDA’s reforms. (They’ve also worked in conjunction with STOP Foodborne Illness and other food safety advocates to modernize salmonella monitoring.) Yet not everyone is on board with USDA’s sweeping new proactive approach.

The industry group National Chicken Council (NCC) has been particularly vocal in its dissent. “[USDA] is formulating regulatory policies and drawing conclusions before gathering data, much less analyzing it. This isn’t science — it’s speculation,” said Ashley Peterson, NCC’s senior vice president of scientific and regulatory affairs in a statement. “We continue to be disappointed that the agency has failed to use science and research to drive its regulatory policies.”

The statement also noted that guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests heating poultry to 165 F will kill salmonella and other pathogens. The council encouraged “[i]ncreased consumer education about proper handling and cooking of raw meat” to help prevent further outbreaks. (The NCC did not respond to requests for further comment.)

Eskin said that common cooking guidance has proven to be less than reliable. “We’ve encountered cases of people thoroughly cooking their food as directed and still getting sick,” she said. Additionally, even if the 165-degree rule were wholly dependable, that safety burden shouldn’t rest solely on consumers, according to Dr. James E. Rogers. Rogers is a former USDA microbiologist and current director of food safety at Consumer Reports*, one of the organizations that has repeatedly petitioned USDA for salmonella reform.

“The question I’ve always asked is whether these companies do a financial analysis to say, ‘We can absorb a certain amount of loss each year from food poisoning outbreaks.’”

“We have seen in a number of studies — including studies done by the USDA — consumers don’t wash their hands regularly. Consumers do not clean their countertops. Consumers do not use separate cutting boards, they do not use regular hygiene in the kitchen consistently enough to protect themselves,” he said. Rogers believes that upstream salmonella prevention efforts can work in conjunction with increased consumer education. “We advocate that you send [consumers] clean, safe products first.”

Part of the issue, according to the NCC and other industry critics, is that poultry farmers will be newly responsible for a demanding — and potentially expensive — burden. USDA plans on incentivizing poultry farmers to “reduce the level of incoming Salmonella contamination or mitigate the risk of a particular serotype entering the [slaughter] establishment,” according to the FSIS proposal. Eskin said the “incentive” may simply be that it’s in a farmer’s best interest to ensure their end product can make it to market.

Rogers agrees, noting that the current recall structure, where products are pulled only after they’ve been well-proven to make people sick — and even then only voluntarily — is clearly not working. “The question I’ve always asked,” he said, “is whether these companies do a financial analysis to say, ‘We can absorb a certain amount of loss each year from food poisoning outbreaks. They don’t come that often, right?’”

But considering how many hospitalizations and deaths continue to stem from salmonella every year, and how many consumers and advocates have demanded stronger regulation of pathogens in the food supply, USDA has determined it’s an unacceptable level of loss. The new salmonella initiative officially launches with a public hearing on November 3, followed by the ambitious goal to get interim regulations in place by mid-2023 and final rules by 2024.

*Disclosure: The writer of this article was once employed by Consumer Reports as an investigative food editor.