Almost all of the world eats goat meat. Here in the U.S., it’s complicated.

It was at Coachella in 2024 that Juan Garcia’s suspicions were confirmed: The people who you might expect to be eating goat weren’t, but everyone else couldn’t get enough of it.

Garcia’s nationally celebrated pop-up and catering company, The Goat Mafia, has been a vendor at the celebrity-studded music festival for the last two years. A fourth-generation birriero from Jalisco, Garcia said he’s found many newer Mexican immigrants and first-generation offspring now shun goat. He said this partly accounts for the widespread substitution of beef for goat in birria, both domestically and in Mexico. That’s why The Goat Mafia stands by its motto: “Si no es de chivo, no es birria.” (If it’s not goat, it’s not birria.)

“It frustrates me,” said Garcia. “My uncle is a birriero in Jalisco, and the use of beef there is to appease the palates of tourists and expats, as well as younger Mexicans who don’t like the flavor of goat … When I was growing up, I’d avoid taking lunch to school because my food was ‘different,’ and now it seems we’re dealing with the aftermath of that, where our recipes and traditions are fading.”

Ironically, goat is increasingly finding favor amongst white consumers in the U.S., primarily those seeking a lean, high-protein or more sustainable meat source. Over the last 20 years, the nose-to-tail and locavore movements have also correspondingly led more chefs from non-goat consuming cultures to use the meat. Goat farmer Leslie Svacina of Cylon Rolling Acres, a 140-acre regenerative farm in Western Wisconsin, said that many of her customers are military personnel formerly stationed overseas or avid travelers.

Still, the American meat goat industry, after experiencing a renaissance in the early 90s, has remained stagnant for the last 25 years, said Kenneth McMillin, a retired meat science professor from the University of Louisiana and longtime goat expert.

“I think it’s hard to get data because with other livestock species, producers want to talk about costs and revenue, but goat people tend to be close-mouthed,” he said. “It might be partly because the public tends to have preconceived notions about what goats eat, and who eats goat.”

The “Poor Man’s Cow”

It’s estimated that 75 percent of the planet regularly consumes caprine. From Africa and the Middle East to Latin America, the Caribbean, and parts of Asia and Europe, goat is a popular protein or a downright delicacy. It’s also lower in calories, fat, and cholesterol than chicken, pork, beef, and lamb, and, at 27.1 grams of protein per 100 gram serving, falls just behind conventional beef, which is 28.6 grams per serving.

Many people find goat delicious, with a flavor and texture that vary depending on the age of the animal and its diet. Garcia describes cabrito, an unregulated term that in Mexico refers to suckling animals, as tasting clean and mild; he’s also a fan of the more flavorful shoulder and loin. Yet many Americans avoid goat because of the widespread perceptions that the meat is rank, gamy, or tough.

“There is an understated goat aroma and flavor,” said goat and sheep farmer Brian Palmer of Salinas, California’s, Turning Leaf Ranch. “But fresh, high-quality goat meat is approachable.” He describes his micro-herd of 100-percent grassfed animals as having “mild, slightly sweet meat.”

Many Americans avoid goat because of the widespread perceptions that the meat is rank, gamy, or tough.

America didn’t always forgo goat meat, but its reputation has always been spotty. According to Tami Parr, author of Goats in America: A Cultural History (OSU Press), caprines were first brought to the Americas on Christopher Columbus’s second voyage in 1493. English colonists also brought goats, but the animals came to be known as the “poor man’s cow.” “If you didn’t have money, you had a goat,“ said Parr. ”Those who were established kept cattle.“

Despite some bias, these early American goats were used for milk, meat, fiber, leather, and landscaping. Goats were — and still are — inexpensive and efficient for homesteaders, requiring less room and feed than cows, and they consume a greater diversity of vegetation.

During the 19th century, the goat’s already tarnished reputation grew worse as they increasingly came to be associated with immigrants and thus, poverty. Then by the mid-20th century, the advent of industrial meat production brought advances in livestock production, processing, and distribution, and a greater emphasis on beef and pork to feed a growing population. Many consumers of the era, wary of the industrial ag complex, became part of a back-to-the land movement that revived the goat’s popularity, but it was the birth of America’s artisan cheese industry in the 80s that finally put goats — specifically their milk — back in the spotlight.

It was the birth of America’s artisan cheese industry in the 80s that finally put goats — specifically their milk — back in the spotlight.

The first Boer meat goats arrived in America in 1993, dovetailing with the Immigration Act of 1990. The goal was to maximize meat yield and profit, and the South African breed is known for its muscular build and rapid growth. “The influx of immigrants from countries like Somalia and Pakistan, combined with the introduction of Boers, really kickstarted the modern meat goat movement,” said Parr.

Regardless of breed, most meat goat producers are small and have other agricultural enterprises to augment their income, if not other occupations; Palmer, for example, is a math professor at a local college. “Most goat producers aren’t profitable,” he said, adding that he got into goats because he wanted a species that could be raised entirely on pasture.

Economics aside, many producers say they’re filling a void within their community or region, and find it gratifying to supply a fresh, wholesome alternative to the frozen, imported goat typically found in ethnic markets. Having access to those markets, however, depends on where you live, which is why some goat meat producers now sell online, despite the added labor and cost. “One of the biggest challenges with the goat meat industry from a consumer standpoint is accessibility,” said Svacina. “There are a lot of people who want it regularly, but it’s hard to find in grocery stores.”

As of January 1, 2026, the USDA reported that there are 2.01 million meat goats in the U.S. The number is up two percent from 2025, “demonstrating their economic value as efficient converters of low-quality forages into quality meat, milk, and hides for specialty markets.” By contrast, a 2025 National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) survey said there were 28.7 million beef cattle in the U.S.

The Other Red Meat

While immigrant populations are largely driving the demand for goat meat, there are curious aberrations, said McMillin. Like Garcia, he noted that demographics are shifting, and increasingly, younger immigrants and first-generation offspring want to assimilate by eating “American” foods like hamburgers — and avoiding goat.

But for many, eating goat is a way to retain their cultural identities or ward off homesickness. “Eating goat was my childhood,” said Garcia. “I was raised in Compton, and when I was little, my dad flew my grandfather from Jalisco to teach him how to make birria. I remember my grandpa showing him how to pinch the spices using three fingers.”

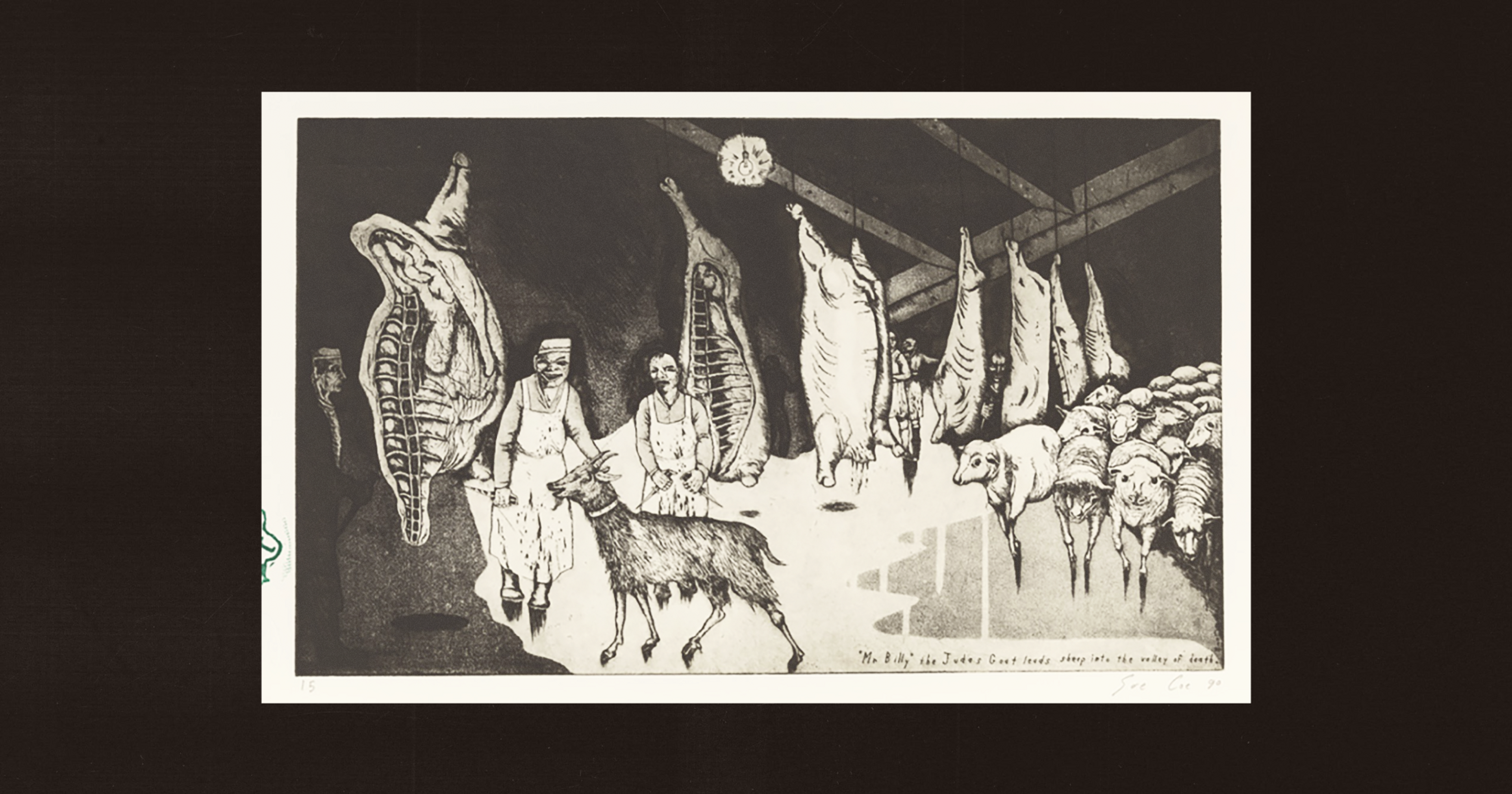

Dishes like Mongolian boodog (whole, boneless goat stuffed with its own meat, offal, vegetables, and hot stones) or Nigerian isi ewu (stewed goat’s head) haven’t yet achieved the popularity of birria, Jamaican goat curry, and Jordanian mansaf (goat braised in spiced yogurt) in America, but different communities want their goat different ways, said Parr. Mexicans prize cabrito, while Muslim consumers request halal meat, particularly that of slightly older animals, which have a stronger flavor. Consumers from non-Muslim parts of Africa and the Caribbean also like mature goats.

Meat source can also impact flavor. Up to 60 percent of the goat imported to the U.S. comes from Australia. These animals are often feral, so “there’s variability on their age, diet, and how they’re raised and handled,” Svacina said. The meat tends to be more distinct in flavor and is usually sold at ethnic markets, but it can sometimes be found at Costco, where it costs a fraction of what domestic producers need to charge.

“Respect the goatiness of the goat. In its native cuisines, goat is glorious, so lean into that.”

“I did the math, and Costco was charging about two dollars a pound,” said Svacina. “Broadly speaking, the economics of it don’t calculate, especially when you factor in the fossil fuel expenditures and environmental impact.”

Svacina charges 19 to 30 dollars a pound for cuts, offal, bones, and prepared foods like sausage and gyro meat, while Palmer sells his meat at a flat 20 dollars a pound. “I don’t know how people do it for less than that,” he said. “We’re a grassfed operation, and goats raised on pasture grow more slowly than those on concentrated feeds. You can also get into quality issues if you feed supplements to make them grow faster.”

Regardless of source, Palmer suggests consumers “respect the goatiness of the goat.” He prefers ethnic recipes like curries or braises that take that flavor into account. “You have to embrace, rather than obscure goat meat. It’s not an equal sub for other species,” he said. “In its native cuisines, goat is glorious, so lean into that.”

The Wild West of Livestock

The meat goat industry is still very much “the Wild West,” said Svacina. Consumer demand and accessibility vary by region, but even with a ready customer base, the numbers aren’t sufficient to galvanize government and other agencies to fund research.

“The organization and food safety and animal welfare regulations are there from a big picture perspective, but the industry is young in terms of infrastructure when compared to other livestock species,” Svacina added. “No commodity group or uniform organization is pushing the agenda.”

What the industry lacks in funding and studies it makes up for in sustainability. Goats are low-impact, nonselective browsers, meaning they eat diverse vegetation, including plants that sheep and cows can’t or won’t eat, like noxious weeds. Sheep and cows also like the same forage and compete if grazed together.

Because they’re small and nimble, goats can access areas other species can’t, and they’re well-suited to land that won’t support cattle or crops. Their tiny hooves have less impact on habitat. “Ten to 12 goats is the equivalent of one cow,” said Svacina.

“The industry is young in terms of infrastructure when compared to other livestock species. No commodity group or uniform organization is pushing the agenda.”

What perhaps limits the potential to industrialize meat goats, however, is their propensity to die without warning. “We do everything we can to save these animals, but it’s hard. Kids can die for all sorts of reasons, including overfeeding,” said Palmer. “Because they require so much vigilance, I say that goat farming isn’t a job, it’s a lifestyle.”

Even so, “If more ag people understood what goats do and can’t do, the industry would grow a lot more,” said McMillin. “They have less facility and acquisition costs and are generally less aggressive ... Cattle and sheep producers don’t understand the synergisms and don’t want the extra effort of including goats with their herds or flocks.”

One aspect of meat goats that is less publicized is their connection to the dairy and cheese industries. “The reality is that both the dairy goat and dairy cow industries sell most of their male offspring to auction or local buyers for meat,” Parr said. “The same is true for older does when their breeding capacity, and thus milk production, declines. Farms simply can’t afford to keep these animals and unfortunately, people just don’t know enough about how food systems work or understand how dairy industries function.”

Sustainable food systems advocate and former chef James Whetlor, the UK-based author of Goat: Cooking and Eating (Quadrille Publishing), puts it more succinctly. “If you eat goat cheese, you have a moral imperative to eat goat meat occasionally,” he writes.

“I think it’s a new beginning for goat, and the demographic isn’t defined yet.”

Clara Hedrich, co-founder of Wisconsin’s award-winning farmstead LaClare Creamery, added, “Today’s consumer is on average, 5 to 6 generations removed from the farm, so most people only want to think of goats as cute, cuddly animals associated with their favorite cheese. They really don’t want to think or even know about the rest.”

LaClare Creamery launched sister company Calanna Specialty Foods in 2018 to market the meat side of the business. “Wisconsin leads the nation in the number of milk goats, which total nearly 80,000,” said Hedrich. “Does usually have twins, sometimes triplets or quads, and about 50-percent of those are male, and only a small number are needed for breeding. To maintain the growth of the cheese industry and keep farms profitable and sustainable, we have a responsibility to utilize the meat side. Years ago, many bucklings were euthanized instead.”

Regardless of the reasons for eating goat, the bottom line is that domestically sourced animals offer a nutritious, sustainable alternative to industrial meat production and provide a revenue-driven outlet for the commercial dairy industry. But it’s up to consumers, no matter their provenance, to ask for it.

“I think it’s a new beginning for goat, and the demographic isn’t defined yet,” said Garcia. “Personally, it’s important for me to carry on my family legacy, which is also my cultural heritage. It’s a real human thing to share food and stories, and if I stopped making [goat] birria, over 120 years of history within my family would disappear, along with a major part of birria culture in Tamazula.”