New research exposes how America’s beef industry is increasingly propped up by the consumption habits of middle-aged men.

When Justin Robbins, a sixth-generation cattle farmer from Scranton, Iowa, walked into this year’s annual Cattlemen’s Association Banquet, he was pleasantly surprised. The room was full of new faces, young faces, and more overall bodies than they’d seen in quite a few years.

“These were people wanting to be involved. And that to me is exciting, because cattle producers are aging out globally,” said Robbins.

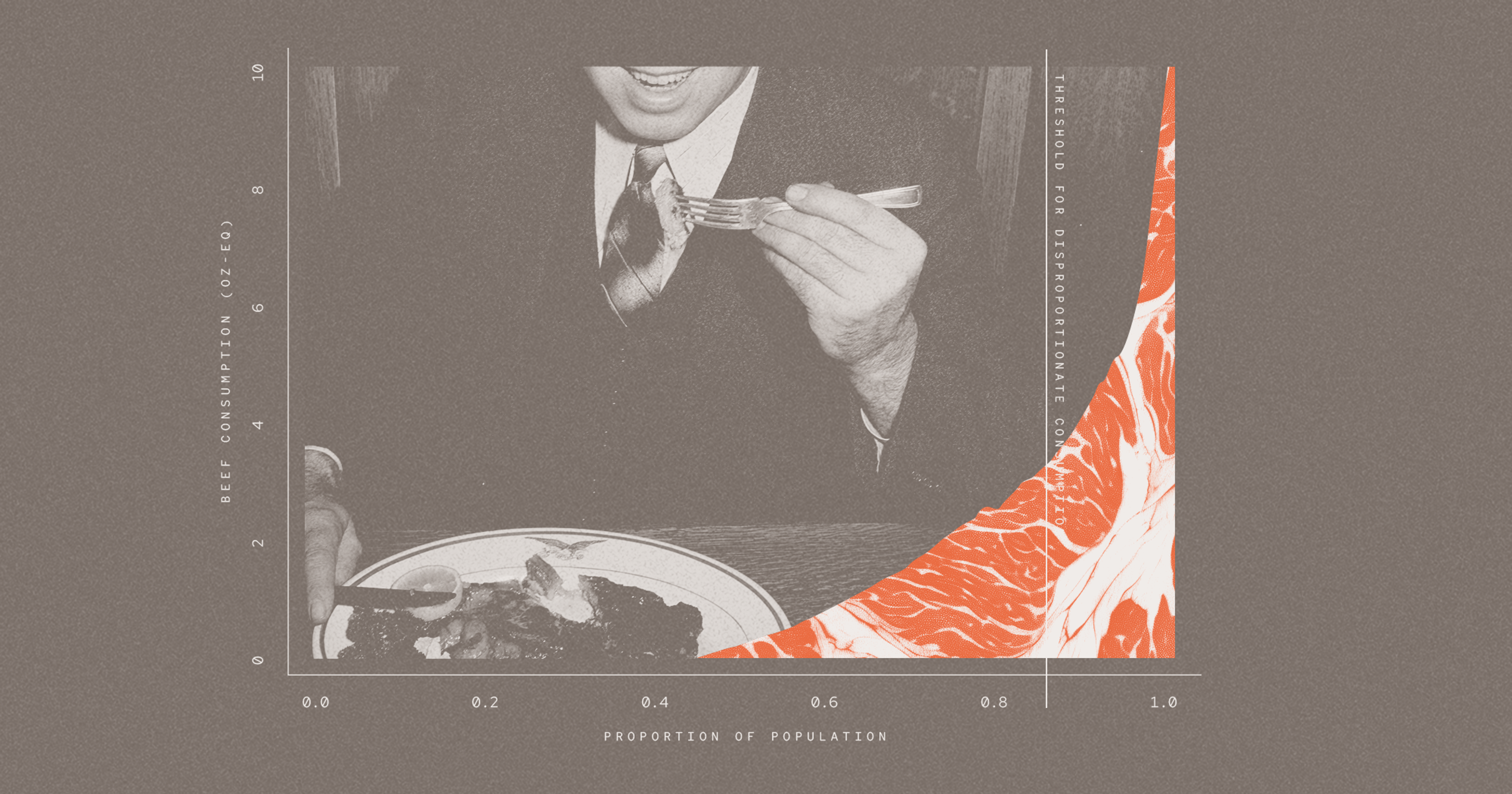

As it turns out, beef producers aren’t the only ones getting older. A recent study from Tulane University in New Orleans found that 12 percent of Americans account for 50 percent of beef consumption in the U.S. Most of this consumption is done by middle-aged males, while beef consumption is lower among younger consumers and college graduates. The study is sparking concerns — and hopes — that America’s population could be aging out of beef.

It’s certainly true that cultural attitudes towards beef have been shifting. Cattle production has come under fire for everything from farmland destruction to rising greenhouse gas emissions, poor health outcomes and more. On top of that, the market for plant-based meat products continues to grow, offering consumers new alternatives to beef.

Mark Rifkin, senior food and ag policy specialist at the Center for Biological Diversity, which helped fund the Tulane study, said that, perceptions aside, beef intake is still forecast to grow globally.

And overconsumption, even if by a small subset of the global population, remains a concern when it comes to environmental protection. “If everyone in the world ate the diet of an American, we’d need 2.5 Earths to provide that much land,” said Rifkin. “We simply don’t have the land.”

Still, if a small subset of America’s population is doing the majority of beef consumption, why do global averages continue to grow? Studies show factors like increasing global wealth and rising populations are driving beef consumption worldwide.

America currently exports around 38% of its beef, with countries like Japan, South Korea, and Mexico being the largest importers — countries where beef consumption is on the rise. Changing attitudes towards beef at home could simply push American-made beef into new markets.

Even if interest in beef does decline, consumption of other meat products, particularly chicken, is growing. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) 2022 Census of Agriculture reported more than 7 billion chickens on mega factory farms in America. Chicken farming contributes to toxic waste run-off, rampant Avian Flu, global greenhouse gas emissions, and more.

“If everyone in the world ate the diet of an American, we’d need 2.5 Earths to provide that much land.”

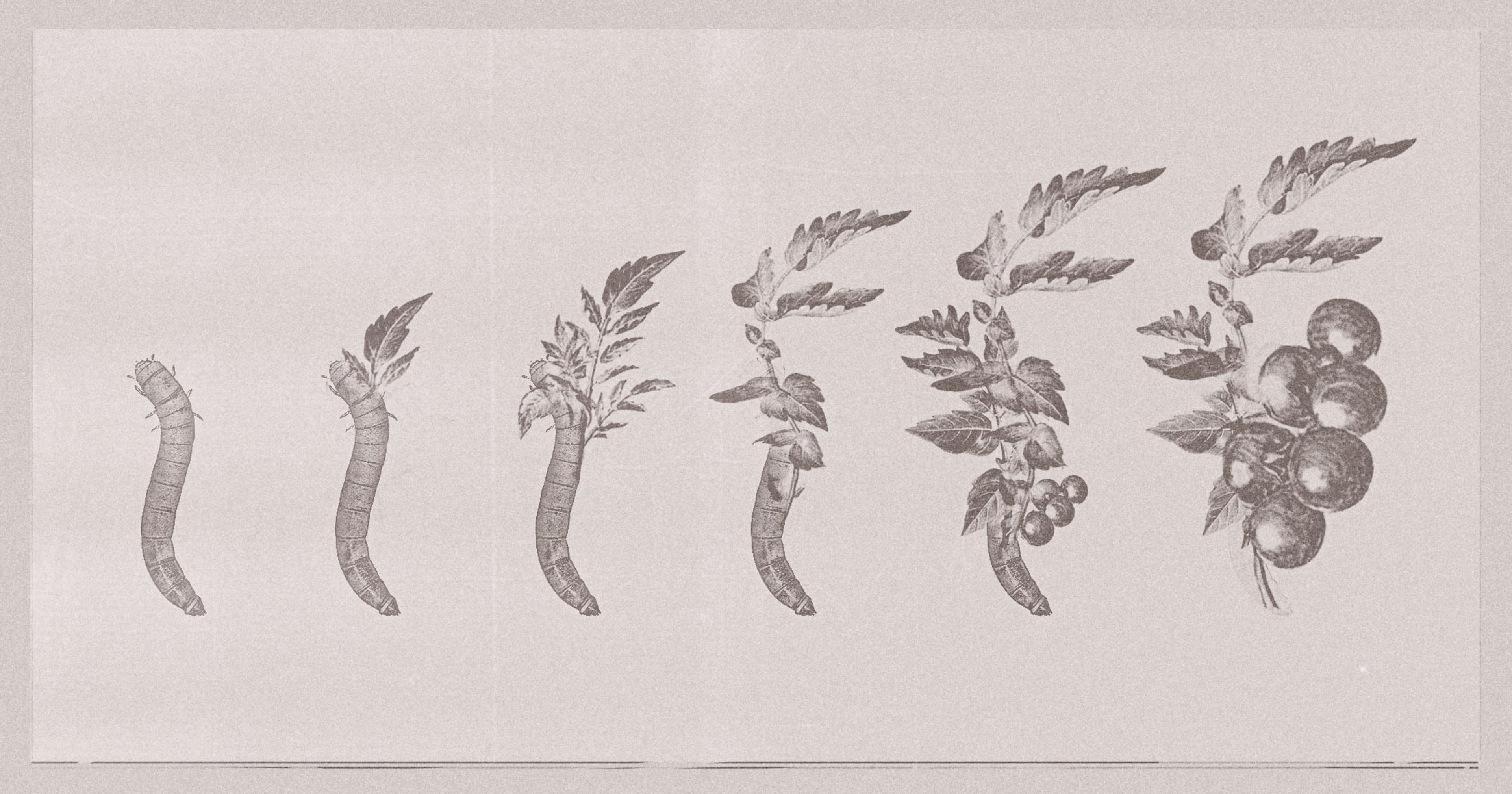

While large, industrial farms bear the brunt of the climate responsibility stateside, a new wave of regenerative cattle farms, like Robbins Land & Cattle, operated by Justin Robbins and his wife Lacie, believe not only that the practice can be done responsibly, but that raising beef cattle can have a positive impact on farmland. “If you let the cows go out and graze it, they are fertilizing it and mixing up that top bit of ground … creating life,“ he said.

“I would love to see every farmer have 20-40 cows,” added Robbins, “because I think every farmer has certain pieces of ground that need to be left alone and not farmed traditionally.”

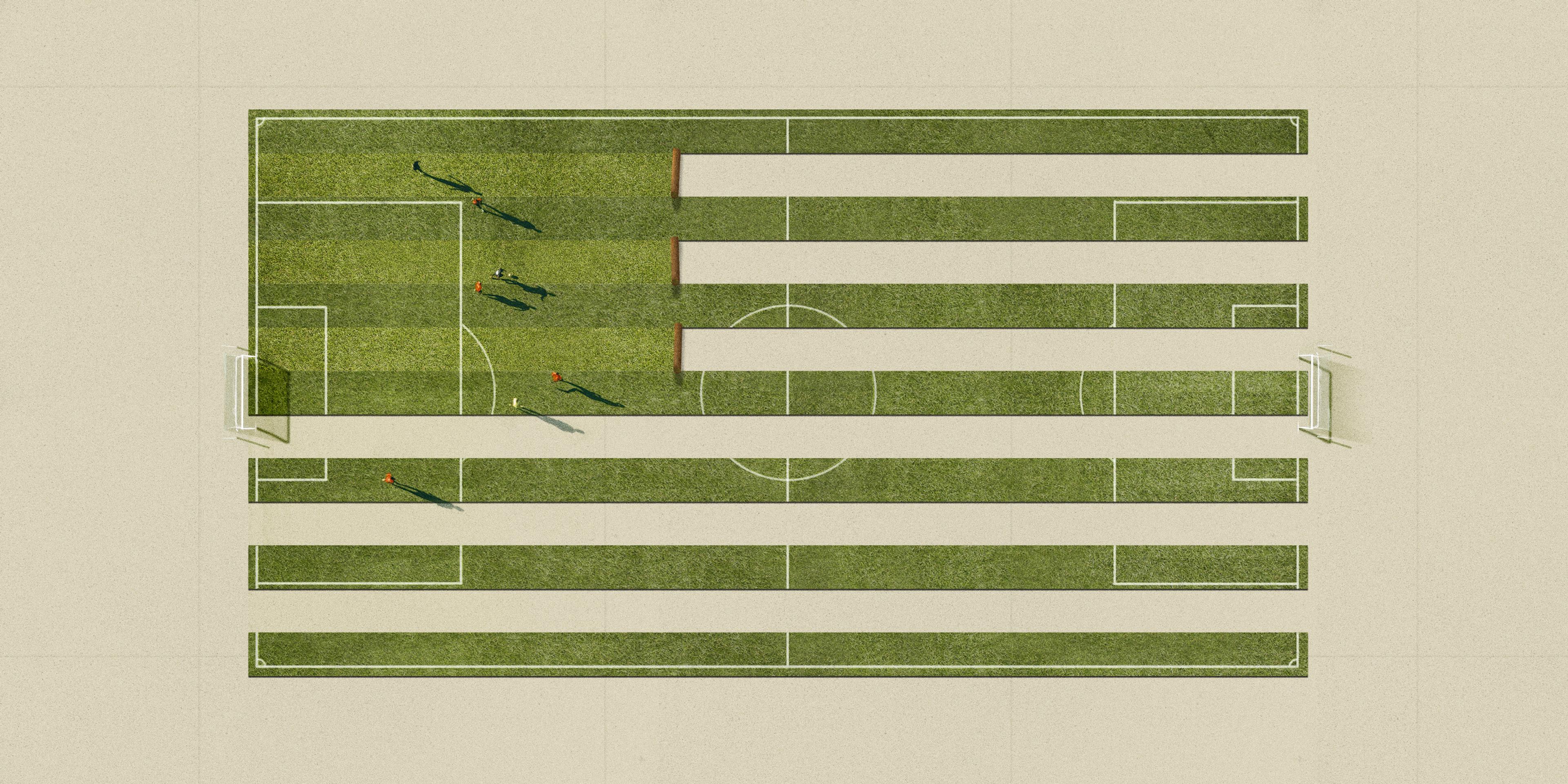

However, the reality of American farming isn’t always green grass and sprawling fields. Industrial farms can hold as many as 150,000 head of cattle at a time, and grazing these animals sustainably just isn’t possible. In addition, the waste created on these farms is a threat to soil, not a boon. It’s estimated that factory farm animals release 1 trillion pounds of manure annually.

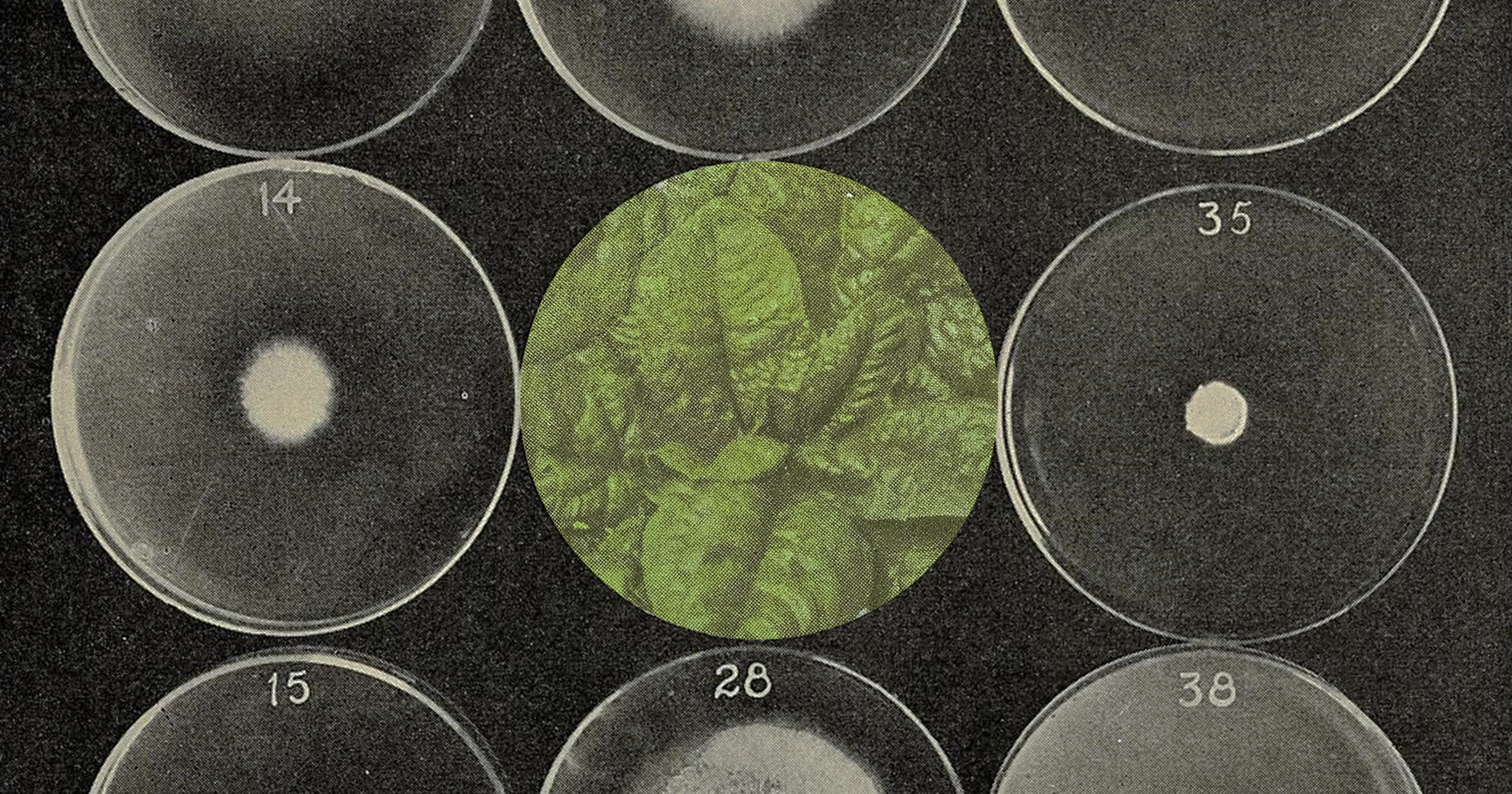

Diego Rose, lead researcher of the Tulane study, has been studying food access and sustainable diets for nearly two decades. He agrees that beef is “an environmentally taxing food source,” especially when it comes to large-scale feedlot operations.

Rose’s study began as an exploration of the “highest carbon eaters” in the American population. Alongside his team, he collected dietary data from 17,000 Americans, using a 24-hour recall method, and connected it to an extensive database of food-related environmental impacts.

“It’s the working class people that show up to our farm. That’s who’s buying the beef.”

Rose said he wasn’t surprised to find that disproportionate beef eaters were the worst environmental offenders. “Beef is 8-10 times more impactful [on the environment] than chicken on a weight-to-weight basis, and 50 times more impactful than beans,” he said.

Still, while 12 percent of the population eat more beef than the rest, 45 percent don’t eat beef at all on a given day. Rose’s team also found that most beef consumption was in mixed dishes like pasta sauces, burritos, and casseroles, which gives him hope that substitutions can be made. Ideally, these substitutions involve more plant-based options, as recent reports show that lab-grown meat may have a worse carbon footprint than farmed beef.

Back in Iowa, Robbins said that despite the findings of the study, he doesn’t see his younger clientele, or the new generation of Cattleman’s associates, slowing down. Though he understands how college kids might have shifting perceptions around eating beef, he blames any downward trends on growing debt and shrinking incomes, rather than a wider ethical shift. “It’s the working class people that show up to our farm,” he added. “That’s who’s buying the beef.”

He does notice more questions from the public around beef impact and future viability, recounting a recent conversation with a woman who asked him: “Why do you farm beef cattle if it’s so bad for the environment?”

Robbins isn’t insulted by these questions. In fact, he’s happy to debate cow farts, plastic milk bottles, and overspent farmland any time. He is, however, quick to reassure any dissenters that cattle can be part of sustainable farming practices. “I wholeheartedly believe beef is a sustainable food if it’s raised properly,” he stated. “It’s no different than living within your means.”

For Rose, it’s unclear whether a future exists without beef as a mainstay of the American diet. Still, he said, “We really weren’t trying to pick on people, we’re just trying to see how it shakes out, and what information might be useful to those that want to educate folks.”

“Not everybody is going to change their diet, and we aren’t suggesting a ban,” he added. “But the planet is on fire … so we need some people to step up and do something about it.”