As tensions have risen between owners of working cats and conservationists concerned with their environmental impacts, a beloved pastoral mainstay may be slipping away.

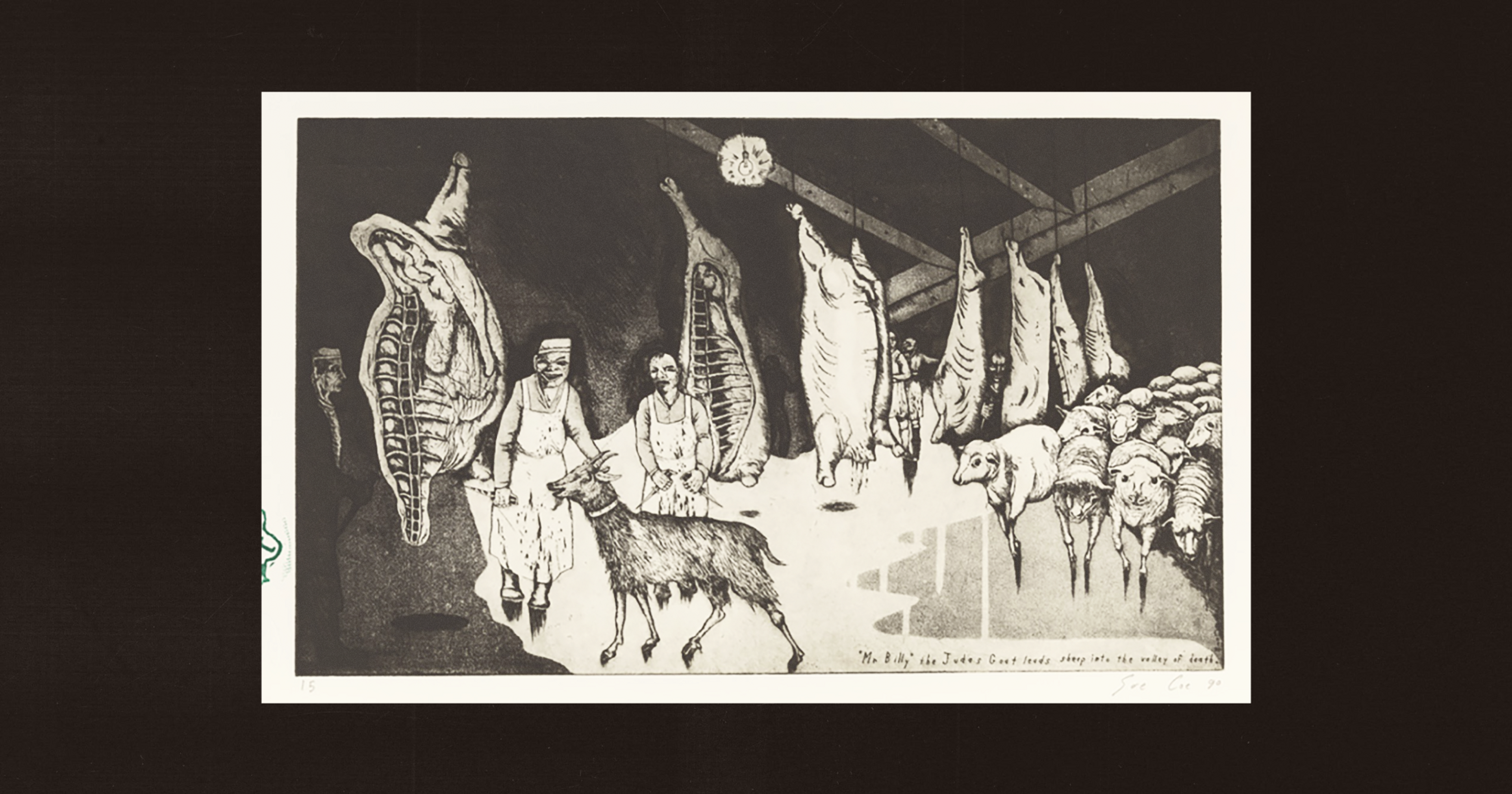

The notorious barn cat — perched atop a tractor, chasing mice, napping on bales of hay — was a sight once seen on virtually any American farm. Beloved for their pest control skills, domesticated felines arrived in North America in the early 1600s and quickly put themselves to work for farmers. Now, barn cats are fading from many of their former haunts — and many believe their disappearance is long overdue.

It’s estimated that there are 70 million unowned and/or feral cats in the U.S. — neck and neck with the 85 million cats owned by people. With even conservative estimates finding that outdoor cats kill up to 1.4 billion birds and 22.3 billion mammals each year in the U.S. alone, it’s hard to say that ecological impacts of barn cats are limited to the farm.

I grew up in Durham, North Carolina, where feral cats lurk around every corner. I don’t remember a time without them — our elderly neighbor managed a constantly fluctuating colony that always contained at least 40 cats, and they often strayed into our yard. There were many magical moments — finding kittens outside of gas stations, or being followed home by friendly strays — but they were often accompanied by the troubling reality of these cats’ lives.

In 2022, Durham banned the euthanasia of feral cats within the county. With over 60,000 feral cats in the city alone, this was a breath of relief to many who loved their communities’ cats — and a shift into panic mode for the area’s conservationists. The county agreed to establish a TNVR (trap-neuter-vaccinate-release) protocol to slow the population’s growth, a method touted by many feral cat advocates.

However, science says otherwise: It’s incredibly difficult to spay and neuter every cat in a colony, and leading studies found that at least 70% of the population must be altered to prevent population growth, which may rebound later anyway. Having grown up with feral cats who grew so friendly they would greet me when I returned home from school, but also having fostered a lifelong appreciation for local ecosystems and birds, Durham’s decision made me feel conflicted. Residents advocating for feral cats believed this was a success for animal welfare — but what about the ecosystems suffering under the pressure of tens of thousands of free-roaming cats?

And where is the line between legitimately feral felines and working cats, allowed to wander free on farms? To people who don’t know them, it’s incredibly hard to tell the difference between a feral cat and an owned and beloved working barn cat.

“Barn cats and house cats in particular have solidified themselves as important, even key components to a high-yield agricultural enterprise.”

It can be hard to conceptualize the damage that even one barn cat could do to its surrounding ecosystems. But experts in the field warn that their threats to wildlife are too often overlooked. I spoke with Courtney Donkersteeg, an avian biostatistics analyst at Carleton University in Canada. Donkersteeg is far from a cat hater — she empathizes with those who keep barn cats around, even against current advice.

“Barn cats and house cats in particular have solidified themselves as important, even key components to a high-yield agricultural enterprise,” she said. “Much like the working dog, they are both business assets and adorable companions, thanks to our ever-present desire to include every proximal creature in our social circles.” Donkersteeg thinks that cats’ dominance in barnyard rodent control isn’t perfect, but is sensible. “I think that the ways in which they are mostly self-sufficient are enough to be a good competitor with other methods of pest control on farms,” she said.

But although barn cats certainly aren’t the greatest threat to America’s wildlife, their time to shine may reside in the past. “There was likely a time when barn cats were more beneficial than not, but given the modern evidence, I don’t think that is the case anymore,” said Donkersteeg. “The current state of things shows that free roaming and feral cats are one of the primary reasons for avian decline in North America. Birds are a crucial biological indicator for most environments — if something goes wrong with bird populations, that’s usually a sign that other aspects of the ecosystems are suffering and direct, swift conservation action is needed.”

“There was likely a time when barn cats were more beneficial than not, but given the modern evidence, I don’t think that is the case anymore.”

I spoke with Darlene Peterson, a horse rancher in Minnesota and a lifelong owner of both free-range barn cats and indoor cats. Darlene’s barn cats have lived over 14 years with regular vet care, meaning they haven’t seemed to suffer from short lifespans as a result of their lifestyles. “They have the same or higher success rate for catching prey as owls or rat snakes,” she noted. “If you have the means to vaccinate and give them proper veterinary care, spay and neuter them, give them regular food and bring them indoors somewhere overnight it can greatly reduce the risks.”

Peterson’s concern for outdoor cats has changed as she’s gotten “older and wiser,” and while she still keeps barn cats, she believes the practice is maybe more common than it should be. Peterson also anecdotally noted that the bird populations around the farm remain strong, as she’s sighted over 100 species. “Our farm has grassland, woods, and water habitats and many of the bird species regularly nest and return year after year, such as barn and tree swallows, robins, house wrens, Baltimore orioles, grackles, red winged blackbirds and mallards, among others. Even with barn cats running around I think that’s a pretty impressive number.” Of course, that doesn’t mean there’s never any casualties — or that Peterson’s cats are a harmonious part of the natural ecosystem.

Barn cats have their claws sunk into American culture — and many farmers will keep their generations-long lines of barn cats around for as long as they’re working in agriculture. But attitudes are changing, and while vet care and spaying and neutering become more prevalent, so does the other option — forgoing barn cats altogether. Time will tell if we’ll see barn cats disappear, hopefully to the benefit of native wildlife, or if this is one tradition we’re not quite ready to let go of.