Dairy farmers are seeing huge payouts for beef-dairy crossbreeds amid a major beef shortage and bottomed-out milk prices.

Jim Van Patter’s operation in Wisconsin is flush with cash but losing money on milk. At best, the 2700-head dairy he manages in Wisconsin, Nehls Bros Farms, has been breaking even on its central product since milk prices bottomed out in 2023. But Van Patter, like many U.S. dairies, is keeping things afloat thanks to an unlikely buyer — the beef industry.

Five years ago Van Patter exclusively raised, managed, and sold dairy animals. But today half the calves born at Nehls Bro Farms — about 1500 animals — are part beef. The Holstein-Angus crossbreeds are known in the industry as beef-on-dairy and the drought-depleted beef industry is buying them up for a whopping $800 per animal, nearly seven times the value of a dairy calf.

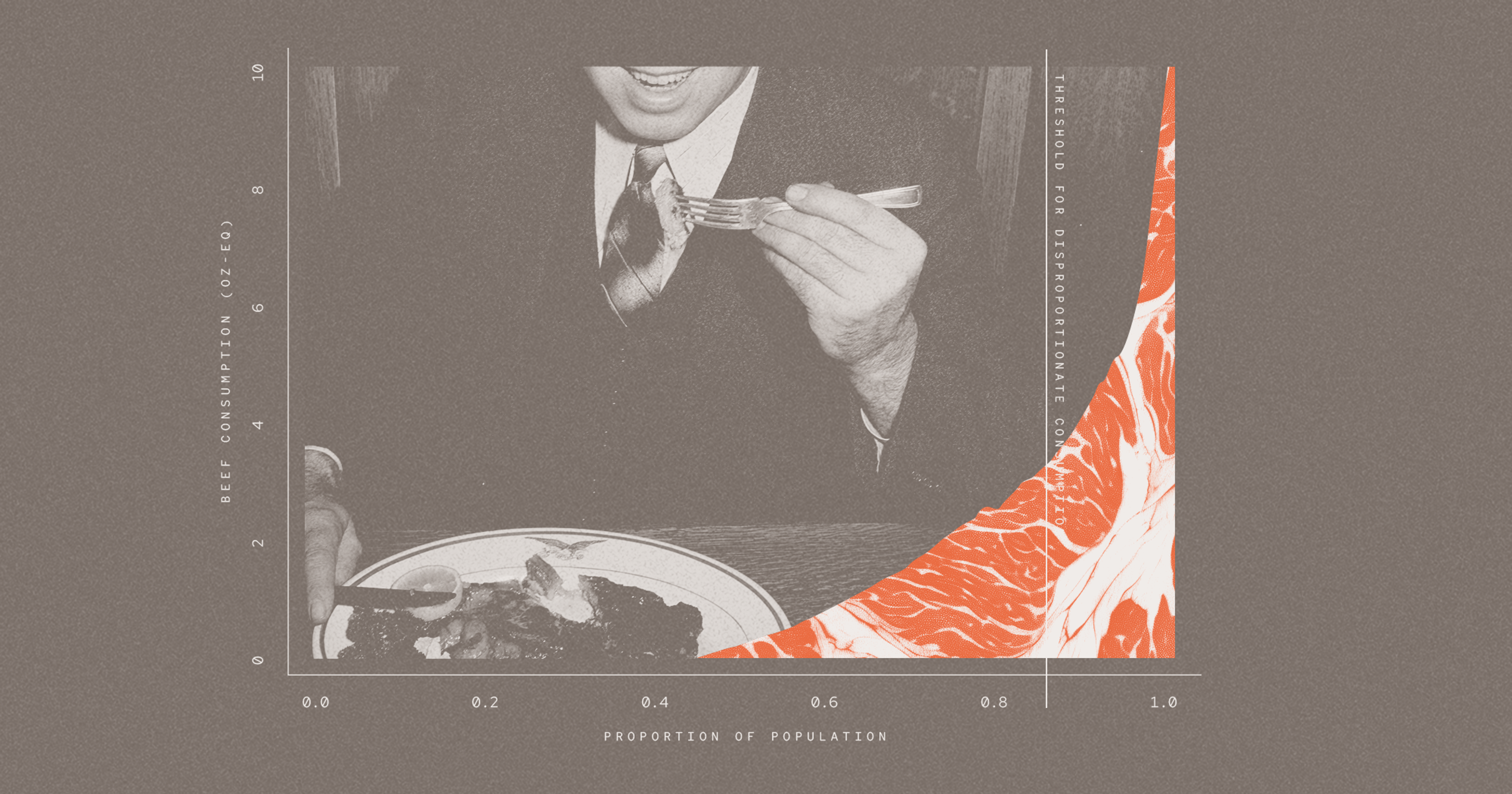

“The [beef cross] calves and culled cows were the only thing turning a profit in the last year,” Van Patter said. The fast cash has dairy producers devoting as many as 70% of their calves to beef crossbreeds, creating the lowest dairy heifer supply in 20 years, and more than tripling the sale of beef semen in the U.S. Experts estimate that beef-on-dairy currently makes up 25% of the U.S. beef supply. In 2024 the most successful dairies are the ones who have aptly adapted to the livestock market.

“Every dairy is a beef cow eventually,” Van Patter said.

That’s always been the case. Dairy animals were in the beef supply well before the recent surge in crossbreeding. Holsteins, mostly culled cows and steers, traditionally make up 20% of U.S. beef. Compared to traditional beef, these calves were sold for rock-bottom prices, needed twice as long on feed, and produced smaller cuts of meat. But in the last six years better breeding technology, packer demands, and a massive drought in cattle country have created an opportunity for dairies to offer a more beef-like animal just when the beef industry needs it.

“With the lowering milk prices, especially the last year, these beef cross calves have been what’s sustaining the dairies,” said Kolton Kreitel, manager of Fullmer Cattle Company, an 80,000-head calf ranch in Syracuse, Kansas.

Calves are a byproduct of mass-producing milk, and Kreitel is in the business of managing that byproduct. His facility takes in dairy calves from two days old so farmers can devote their cows to milk production. But in 2018 a customer called with an unexpected request: Would Kreitel be willing to raise beef crosses instead of dairy animals? The first hundred calves — shorter and blacker than normal — stumbled into his receiving pen a few weeks later. Within a year “it was black calves everywhere,” he said.

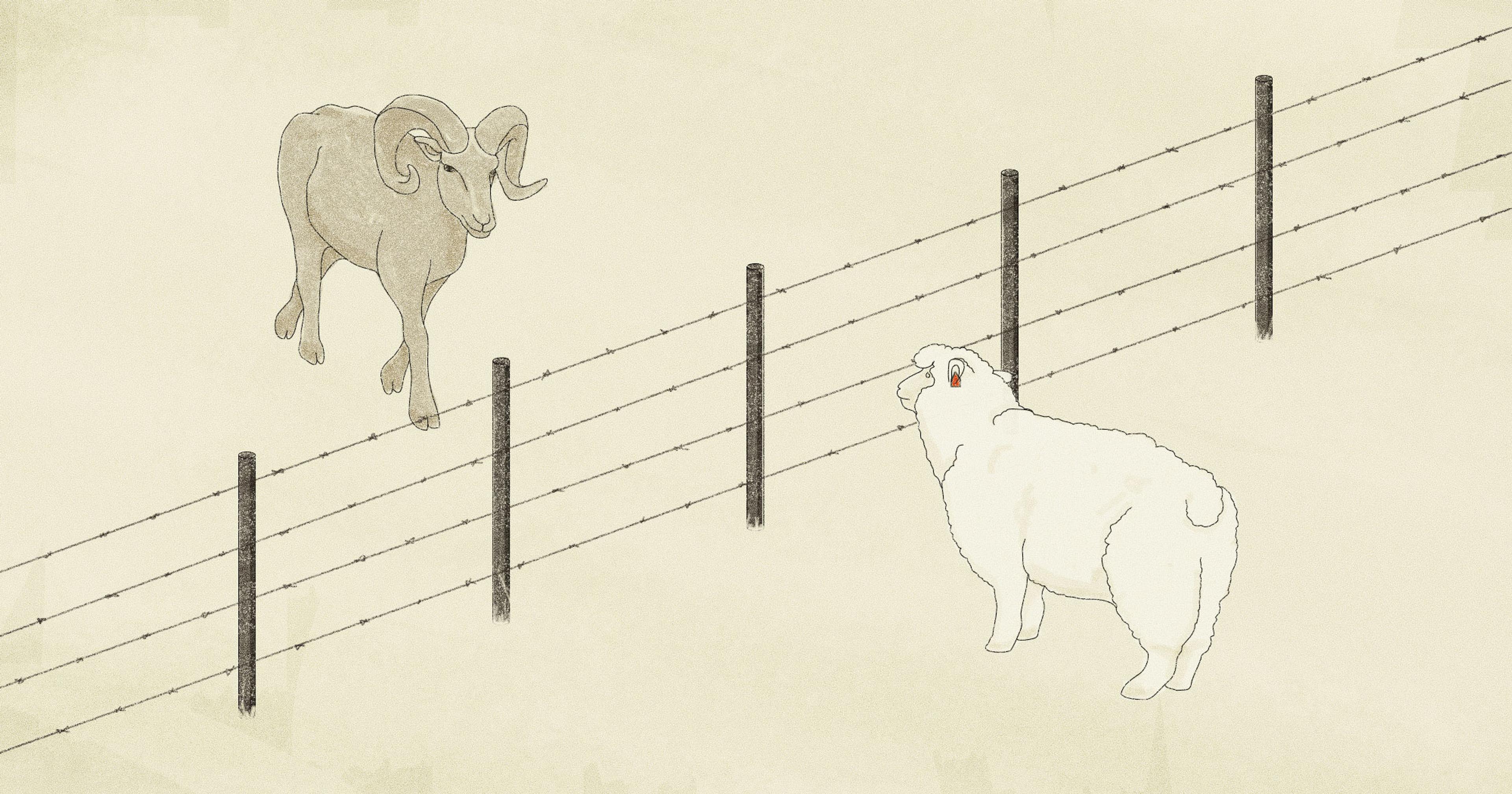

Better breeding technology led the pivot into crossbreeding in the mid-2010s. Every year dairymen breed every animal to keep milk production going, but they only need to keep approximately 40% of the calves to replenish their herd. As sexed semen became more reliable and affordable, farmers gained more control. They could almost guarantee their best cows and heifers would have a female calf. But that also meant they didn’t need a calf from the majority of their herd. That’s when genetics companies started suggesting beef semen, Van Patter recalled.

But the sea change really started when the major meat packers weighed in in 2018, according to Ty Lawrence, professor of animal science at West Texas A&M who collaborates with the four major meat packers: Tyson, Cargill, JBS, and National Beef Packing Co. “This began with Tyson, who was the first packer to say, ‘We don’t want to buy a Holstein anymore,’” he said.

Holsteins pose two main problems for packers. First, they’re much bigger than beef animals, so their long carcasses drag the floor when they’re hung for processing. Their enormous size also means they carry more bone and less muscle, therefore make less sellable meat than their smaller Angus counterparts.

“With the lowering milk prices, especially the last year, these beef cross calves have been what’s sustaining the dairies.”

The second problem is Holsteins have a high rate of liver abscesses, a pus or infection-filled mass on the liver usually caused by bacteria from the rumen. Removing the liver abscesses slows down processing and, depending on the severity, the packer can lose $8 to $260 in offal and meat. The processing plants were effectively losing money on these large dairy animals, so once they had an alternative, they stopped taking them, Lawrence said.

Once packers took their stance, the market for purebred dairy calves dissolved while the hybrid price increased. At first, any black bull would do, and the initial beef-on-dairy crosses were wildly inconsistent in terms of size, metabolism, and rate of muscle gain. “The feedlots weren’t into those cattle because of the variance,” Kreitel said. But the genetics companies quickly refined their offerings, narrowing their pool to bulls that were the best crosses for Holstein.

In a six-year period, beef semen sales tripled from 2.7 million to 9 million units. “I’ve got friends at ABS and they have more beef animals than dairy animals now,” Van Petter said of the Wisconsin-based genetics company.

The crossbred calves proved to have some advantages. Thanks to their hybrid vigor they have lower disease rates. Their meat quality grades are higher because of the superior marbling that comes with their dairy genetics. And they put on more muscle with less feed compared to pure Holsteins thanks to their Angus ancestors.

By 2020 a survey of California dairies showed the crosses were commanding twice the price of a Holstein. Van Patter was making $200 on a cross compared to $50 on a Holstein. Then the beef shortage hit.

In January 2023, Kreitel, who was accustomed to paying $200 a head for beef-on-dairy, got a call from a customer who said they’d been offered $300. Appalled at the sudden hike in price for a calf only 24 hours old, Kreitel declined to match it. But the market soon made it clear that the value of all beef was on the rise.

“This began with Tyson, who was the first packer to say, ‘We don’t want to buy a Holstein anymore.’”

Droughts across U.S. cow country forced beef producers to sell off their herds because they didn’t have the grass and forage to sustain them, said Pedro Carvalho, feedlot specialist at Colorado State University. By summer 2023 the price of a day-old beef-on-dairy was up to $600. In spring 2024 with the native beef herd at its lowest since the 1950s, Kreitel bought day-old crosses for $800 and sold them at 450 pounds for $1600.

“That’s a nice profit margin,” Van Petter said. But it’s easy to get carried away. Van Petter said he’s seen some of his neighbors liquidate too much of their calf crop to beef-on-dairy for the quick cash. They won’t have enough replacement heifers when milk does rebound.

And what happens when the beef numbers rebound? “That’s the million-dollar question,” Carvalho said. Experts from different parts of the industry disagree on the future of the crossbreeds.

Carvalho said prices for crosses, and all cattle, will dip when the beef herd rebounds, but beef-on-dairy will still be of high value. They even have the potential to produce high-quality meat more efficiently. Data from Iowa showed beef-on-dairy animals produce more marbling while staying leaner compared to beef industry averages.

“The number of prime on these cross cattle is significantly higher,” Kreitel said.

Lawrence, however, said changes must be made. For all their improvements, the beef-on-dairy still reported higher rates of liver abscesses. “If packers didn’t have to buy them today they wouldn’t,” Lawrence said. “There just aren’t enough cattle to avoid the dairy crosses.”

The beef herd’s rebound is likely still years away. 2024 projections say the U.S. beef supply is likely to decline further, so beef-on-dairy — and all cattle for that matter — are expected to continue to demand a high price for the next couple of years. That may buy experts like Carvalho time to investigate the crossbreed health issues.

“Once the drought subsides, these critters will have less value,” Lawrence said. “It will not go to zero. It will just be less.”