Autonomous robots are poised to help fix the rural labor shortage. A new institute at Mississippi State gives a platform for students and researchers to experiment with their best ideas.

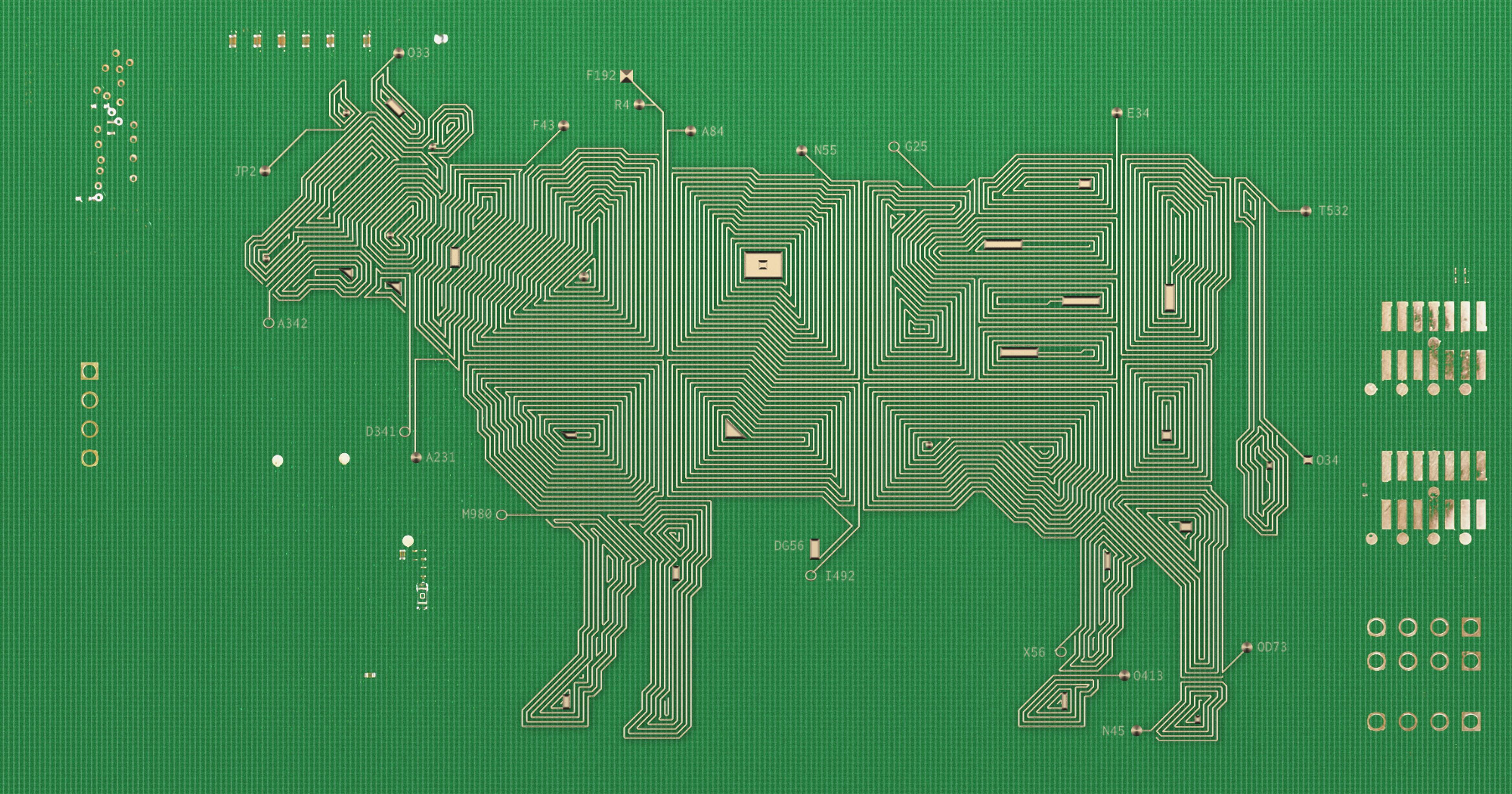

On a sunny spring day in 2023, a fascinating scene unfolded at Mississippi State University’s Bearden Dairy Research Center. Out in a grassy paddock, a small group of cows and calves loped along, followed closely by a squat yellow driverless vehicle topped with cameras and sensors. No humans in sight.

This yellow vehicle, a Clearpath Robotics “Warthog,” was demonstrating the feasibility of fully autonomous cattle herding. To the surprise of the researchers who designed the experiment, the trotting cows behaved completely normally around Warthog, the same way they would around a more traditional person on horseback. This is one of several projects underway at the new Agricultural Autonomy Institute (AAI) at Mississippi State University, the first interdisciplinary research center in the U.S. to focus specifically on autonomous farm technology.

Although only a little over a year old, the institute already has inspired a series of impressive research projects: robotic cotton harvesting and cattle herding, fully autonomous crop-spraying drones, and an unmanned boat equipped to test water quality.

Autonomy in agriculture is nothing new. In 2008, former employees of iRobot, the company behind the Roomba vacuum, founded HarvestAI, which builds autonomous robots that can work alongside humans in a greenhouse. By 2021, 87 percent of U.S. agricultural operations reported using some form of AI, according to Relx, an analytics company — a number that has surely grown in the last four years. John Deere released fully autonomous tractors in 2022. But the array of possibilities is dazzling and continues to grow. One company offers an upgrade to make a regular tractor self-driving. In Germany, researchers prototyped an automatic manure scraping robot that could be used in pig farming. Existing technology can automate weeding, mowing, bird deterrence, and harvesting of everything from strawberries to lettuce.

But are farmers ready?

Large swaths of the rural U.S. still lack the high-speed internet necessary to run wireless technology. The cost of much of the latest technology is prohibitive for smaller operations. And farmers are often hesitant to adopt new equipment without a proven ROI.

“I would tell you, I think we need to move forward with caution,” said Marc Arnusch, who farms heritage wheat, barley, and corn in Keenesburg, Colorado. He’s excited about the prospect of a self-driving tractor, but it’s important to him that whatever technology he’s adopting aligns with the realities of his farm, and that it can be customized. While farmers like Arnusch are eager to explore autonomous tech, they remain conscious of its limits, and especially its flexibility.

Back at MSU, Alex Thomasson, director of the Agricultural Autonomy Institute, acknowledged that some U.S. farmers are likely to move slowly to adopt the new technology. “Is the workforce ready for this? I would say, well, no.” But he believes that the agricultural labor shortage makes the adoption of new technology inevitable.

“To some extent I think growers will have to make this move, because they don’t have a choice.”

“To some extent I think growers will have to make this move, because they don’t have a choice. They’re not going to have the labor that they need to do the things that they need to do.” To help prepare farmers for a more autonomous future, Thomasson said that his institute will be supporting workforce development by working with community colleges and companies to train interested growers. Within the university, AAI employs undergraduate and graduate students to work on research projects, supports agricultural-autonomy coursework, and assists two student agricultural robotics competition teams.

Institutes like AAI, or campuses like the Grand Farm in North Dakota, where farmers can access training and interact with cutting-edge research, are already changing the way U.S. farms operate. But the question of whether autonomous technology will be a satisfactory replacement for human labor — and whether it should be — is a divisive one. This may be especially true for livestock operations, where farmers have both ethical and practical concerns about the role of robots on the farm.

Jamila Jaxaliyeva, a forestry graduate student at the Yale School of the Environment, spent last summer working on Sarah Faith Ranch, about 1.5 hours south of Jackson, Wyoming. She readily acknowledged the difficulty ranches face in finding skilled labor. But although she had used a drone to herd cattle, it had its limits, especially in forested terrain. “You still need riders,” Jaxaliyeva explained. “This technology is not going to replace a range rider.”

Christian Wolpert-Gaztambide, manager at his family dairy farm in Caguas, Puerto Rico, is also wary of replacing human labor. He runs five hundred head of cattle on 650 acres of hilly and partially forested terrain.

I showed him a picture of the cattle herding Warthog and asked if he thought it could work on his farm. Wolpert-Gaztambide shook his head. “It can get really muddy and slimy,” he said, and there are hills and places with steep drop-offs.

“If I automate I’d be cutting three or four jobs. These are people who have been working on the farm for generations.”

He has considered adopting fully robotic milking machines; cost remains the biggest hurdle. He’d have to replace his current infrastructure and invest hundreds of thousands of dollars in new equipment, but money is not his only concern.

“If I automate I’d be cutting three or four jobs,” Wolpert-Gaztambide said. It matters to him to keep good faith with the community. “These are people who have been working on the farm for generations.”

Instead of automating, Wolpert-Gaztambide is trying to expand the size of the milking herd so that he can afford to hire more locals to work on the farm.

“Sure, I’m not maximizing efficiency. But there’s more to agriculture than that. There’s more to husbandry than that.”