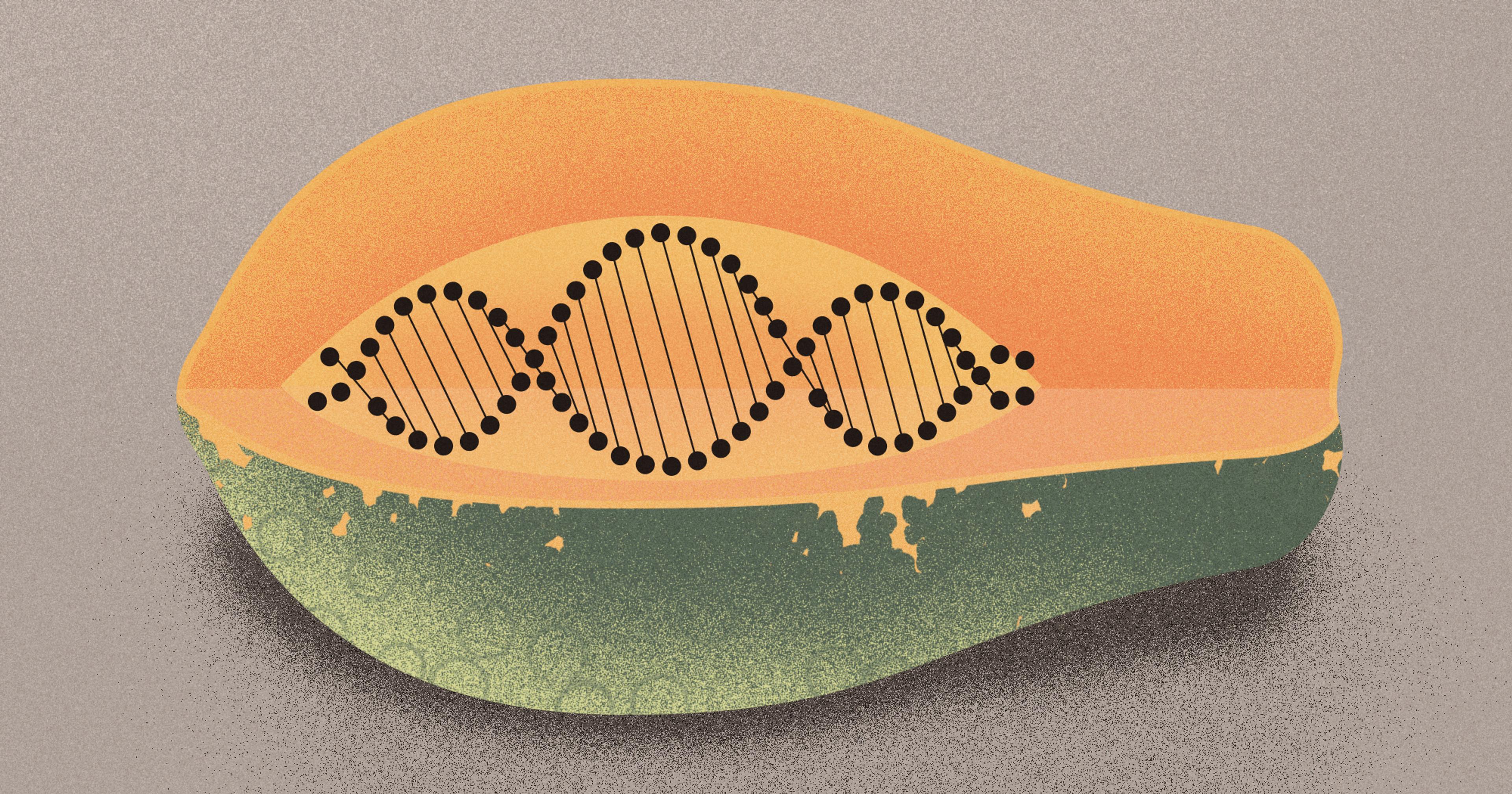

“Plant molecular farming” genetically modifies plants to grow proteins found in meat and dairy products. Boosters say it could make tastier, more nutritious plant-based meat replacements.

Think of plants as mini bioreactors, little factories using energy from the sun to build proteins, says Martín Salinas from his office in Rosario, Argentina.

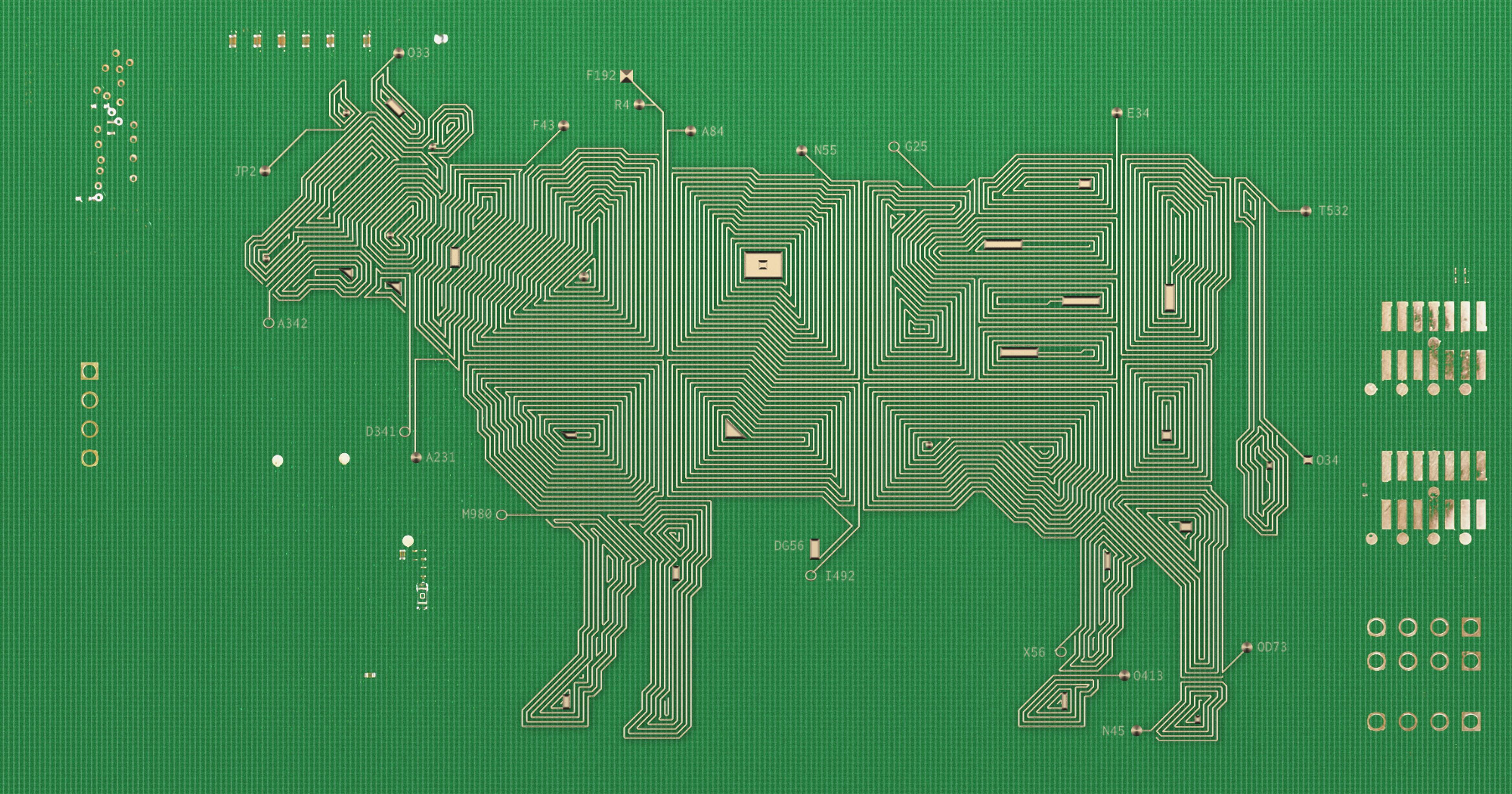

Salinas is a co-founder and the chief of technology at Moolec, an agritech company that produces animal proteins in plants by changing what he calls the “factory” settings.

“We basically change the instructions that the plant has to produce its protein — we give the plant a new recipe [to follow],” he said. This genetic “recipe” comes from public databases and doesn’t require using an animal to start the process. Once the protein recipe is introduced to one plant, all its offspring will naturally carry the instructions and make the protein on their own. “It’s a more efficient, cost-effective way to produce new proteins,” said Salinas.

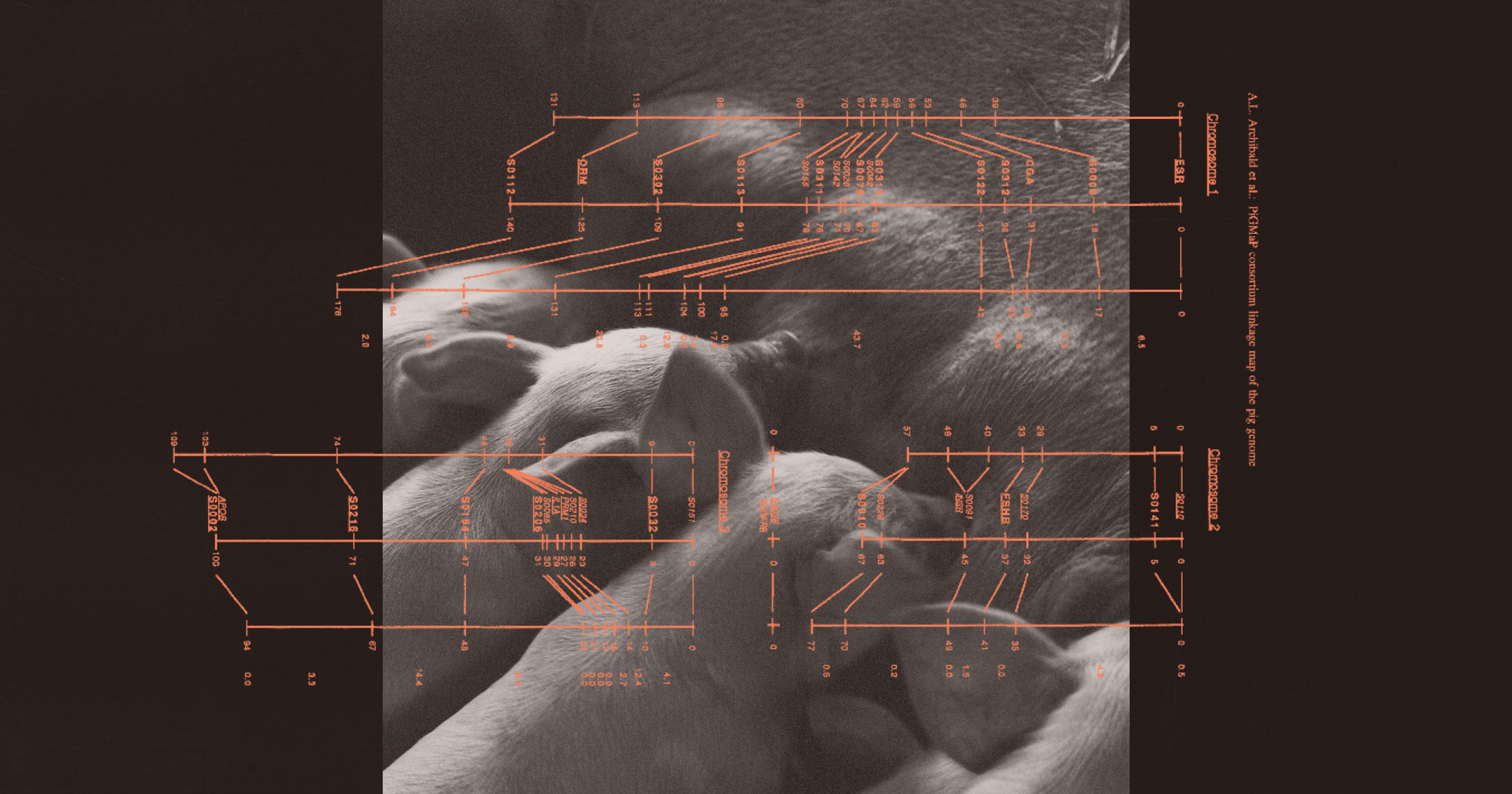

After receiving USDA approval to carry out field trials, Moolec harvested their first batch of “Piggy Sooy,” a pork-infused soybean last year. Their pea that produces beef protein was recently approved to begin field trials.

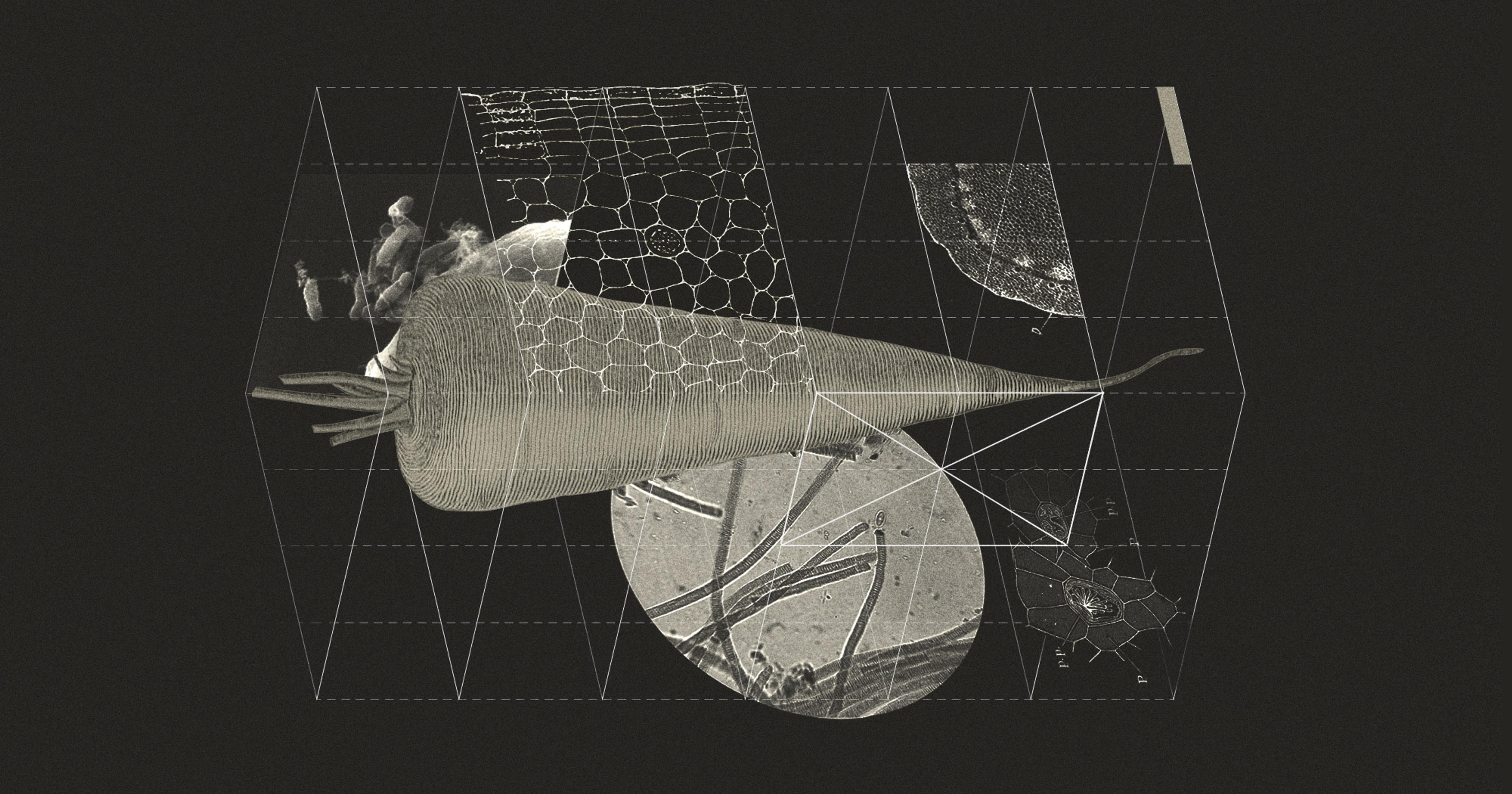

Moolec’s technology is known as plant molecular farming. It’s been used by the pharmaceutical industry since the 1980s for vaccines; about a dozen companies globally are now looking at its potential for the alternative proteins market. Like anything GMO-related, its detractors question if it is actually a sustainable solution. Meanwhile, proponents say it has the potential to make animal proteins more efficiently and humanely, and improve the color, nutrition, and sensory experience of alternative meat and dairy products.

“To date, alternative proteins are mostly an oil and starch mixture,” said Adam Leman, principal scientist of fermentation at the Good Food Institute (GFI), an alternative proteins think tank. Add meat proteins into the mixture and you could have tastier, more nutritious alternative meat products, he explained.

“If you were to take the example of something like a plant-based burger made with soy or pea, you could have an improved taste or aroma, a more meaty flavor that gets added into these,” he said. “I think that would be something that would make these products more appealing and better replicate that experience people are looking for.”

It’s not just meat proteins. Companies are using the same approach to grow dairy proteins and sweet proteins for sugar replacement inside plants.

Leman said one benefit of growing proteins in plants like soybeans or corn is that we already have ways of using the products derived from them. He gave an example of making soy meal or corn meal. “There are already ways that we know to valorize and really use those products in our food system,” Leman said.

“If you were to take something like a plant-based burger made with soy or pea, you could have an improved taste or aroma, a more meaty flavor.”

These advancements could be the bump the U.S.’s stagnating plant-based retail market needs. Though the market grew from $3.9 billion in 2017 to $8.1 billion in 2023, unit sales declined in both 2022 and 2023, according to a report from GFI. The report cites taste and price performance as the industry’s biggest hurdles.

That matters because of the role plant-based food can play in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions. One analysis by the Boston Consulting Group estimated that increasing the global market share of alternative proteins from 2% to 8% by 2030 could have the same impact as decarbonizing 95% of the aviation industry. Another study found that cutting a person’s red meat consumption by half could reduce their carbon footprint by 25%.

Though several studies have found plant-based meat products to have a significantly smaller environmental impact than meat production, some analysts say there’s still a lack of transparency from alternative meat companies about their overall emissions. An exact study of the environmental impact of products made from plant molecular farming has yet to be conducted since the industry is in its beginning stages; no products are currently on shelves.

Leman from GFI and Salinas from Moolec also view plant molecular farming as a solution to food security and future protein supply.

“The population of the world is growing and our arable land continues to dwindle, so having really efficient ways of making protein is good,” said Leman. “In places where you have established agricultural infrastructure, there’s a lot of readily adaptable parts of plant molecular farming that fit in well with what people are doing today.”

In an article authored for Frontiers, members of the American Soybean Association wrote that plant molecular farming could help row crop farmers diversify their operations and boost their income.

“It’s Not About the Bean.”

The ideal result of plant molecular farming is an affordable, more nutritious, better-tasting alternative meat that’s sustainably produced. But products made from plant molecular farming are still years away from hitting the shelves and their exact benefits remain to be seen.

With Moolec’s first Piggy Sooy field harvest, the co-founders were excited to see that they did successfully grow pork myoglobin inside soybeans. On average it made up about 10% of the bean’s weight and turned the beans’ insides a light pinkish hue, similar to a slice of raw pork instead of the creamy white color of standard soybeans.

Moolec’s Salinas said this could reduce the need to add colorants to plant-based products. In addition to giving meat its color, myoglobin is an important dietary source of iron and it’s closely associated with the taste and mouthfeel of meat. It’s what makes meat alternatives appear to “bleed” and what the Impossible Burger aims to mimic in its patties.

But Moolec co-founder and chief product officer Henk Hoogenkamp said it’s too early to make claims about the nutritional profile and sensory experience of Piggy Sooy. This is partly because soy is heavily processed and the end product can vary a lot from soy sauce to tofu to veggie patties.

[The pork] made up about 10% of the bean’s weight and turned the beans’ insides a light pinkish hue.

“It’s not about the bean itself. We don’t want to talk about what the bean tastes like, we want to talk about what the product is like,” Hoogenkamp said. “Any place that’s currently using soybeans could plug our product in, but after their processing, we need to re-evaluate what the advantages are: Is it texture? Is it taste? Is it color? Is it nutrition?”

Hoogenkamp said they aim to start processing the beans next year after scaling up their field trials. He said they are also looking at a variety of applications for their soybean, including in pet food or as a meat additive.

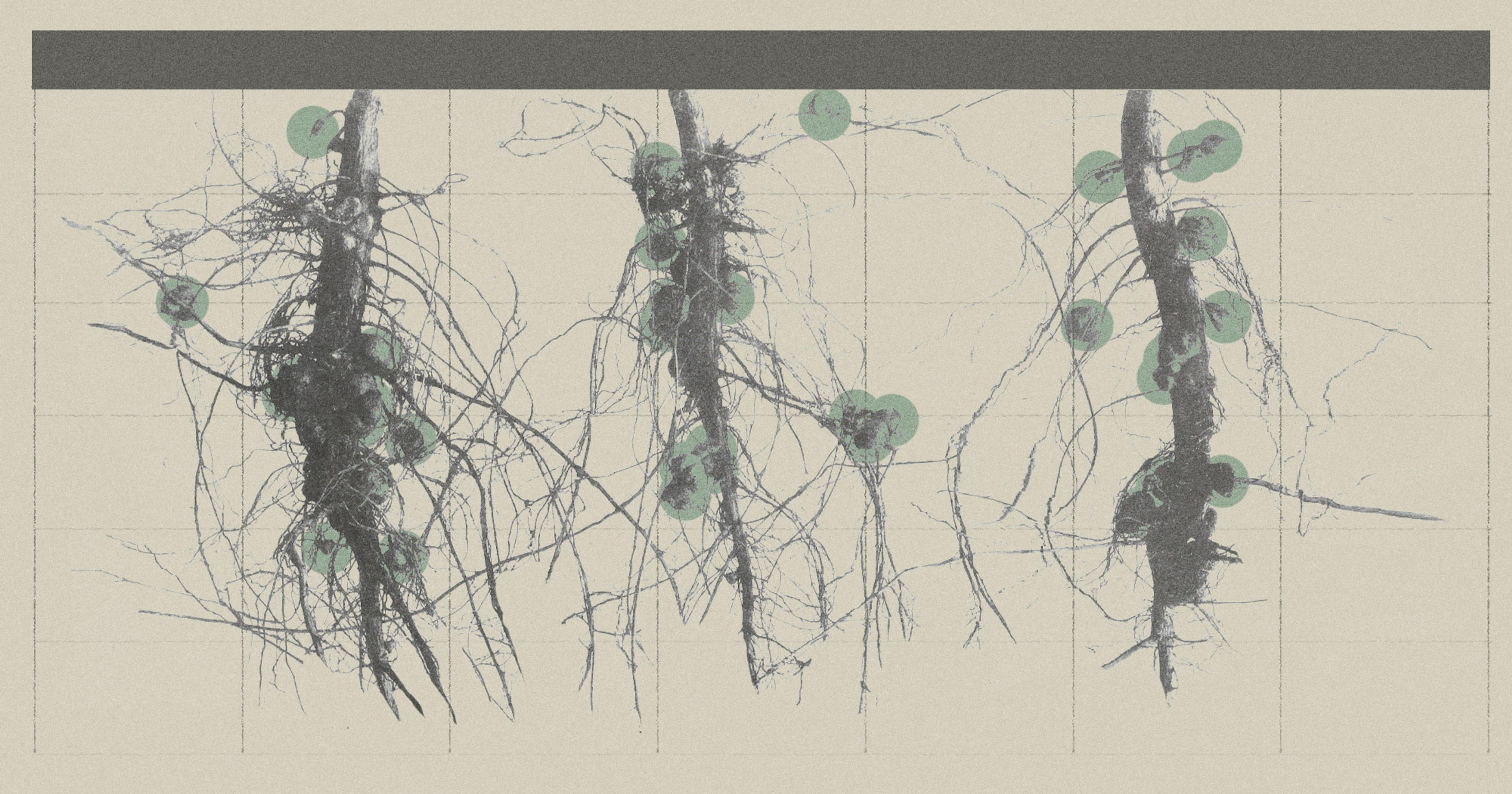

Another variable that needs to be evaluated is what the tradeoff is for producing myoglobin, according to Hoogenkamp.

“The plant is sacrificing something else to make this myoglobin,” he said. “What is it making less of? It could be another protein, it could be oil, could be carbohydrates, so that’s what we’re trying to find out right now in actual field conditions and places where soybeans are grown: What is that penalty? Is there a penalty at all? And what would be the benefit?”

Creating a Problem to Fit the Solution?

Not everyone is convinced plant molecular farming and its pork-protein growing soybeans are the solutions they claim to be.

“I think it’s so silly. I think most of this stuff is really silly,” said Julie Gutham, a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was part of a research project that looked at Silicon Valley’s role in the food and ag tech sectors. “It feels like it’s something they could do, and then they went looking for a problem they could address, which is what we see over and over again.”

Guthman co-authored two research papers and a book — The Problem With Solutions — that analyze the tech sector’s obsession with protein.

“While innovators and investors act as if protein needs this sector to solve an impending crisis and bring its possibilities to fruition, we suggest the inverse — that without protein the sector would be nearly barren of novelty and food, much less the disruption and impact routinely claimed,” she wrote in one of the papers.

Guthman said her other concern with these types of technological innovations is that they’re patented.

“If this is really to solve some big social problem, which I don’t think it really is, why is it always under these proprietary wraps?”

“If this is really to solve some big social problem, which I don’t think it really is, why is it always under these proprietary wraps?” she said.

Matthew Greco from the Instagram account MyHealthForward shares this concern.

“I believe that inventions like this actually increase the risk for food insecurity because they allow companies to patent and control the food supply,” he said in a recent video. “This would inevitably shift grocery store shelf space and consumer spending away from local farms and towards centralized companies.”

It will still be several years (Moolec is hoping for 2027) before these products could hit the shelves, and in what capacity remains to be seen. One reason plant molecular farming has such a long timeline is that it takes a while to develop and research plants.

“Plants grow slowly, they move at their own pace,” said Leman from GFI. “It’s still just so early days.”