“Electro-agriculture” is a nascent concept that explores plant growth without photosynthesis. It could revolutionize vertical farming.

Despite all the innovations that have changed farming over the last 12,000 years, from the introduction of the plow to the development of genetically modified corn, one fact has remained constant: Plants need sunlight to grow. It’s been that way since some of the planet’s earliest bacteria began using photosynthesis more than 3.5 billion years ago — the same cycle plants go through today. The process harnesses the energy of sunlight to move atoms from carbon dioxide in the air to the cells of the plant, building up the biomass needed to produce a crunchy leaf of lettuce.

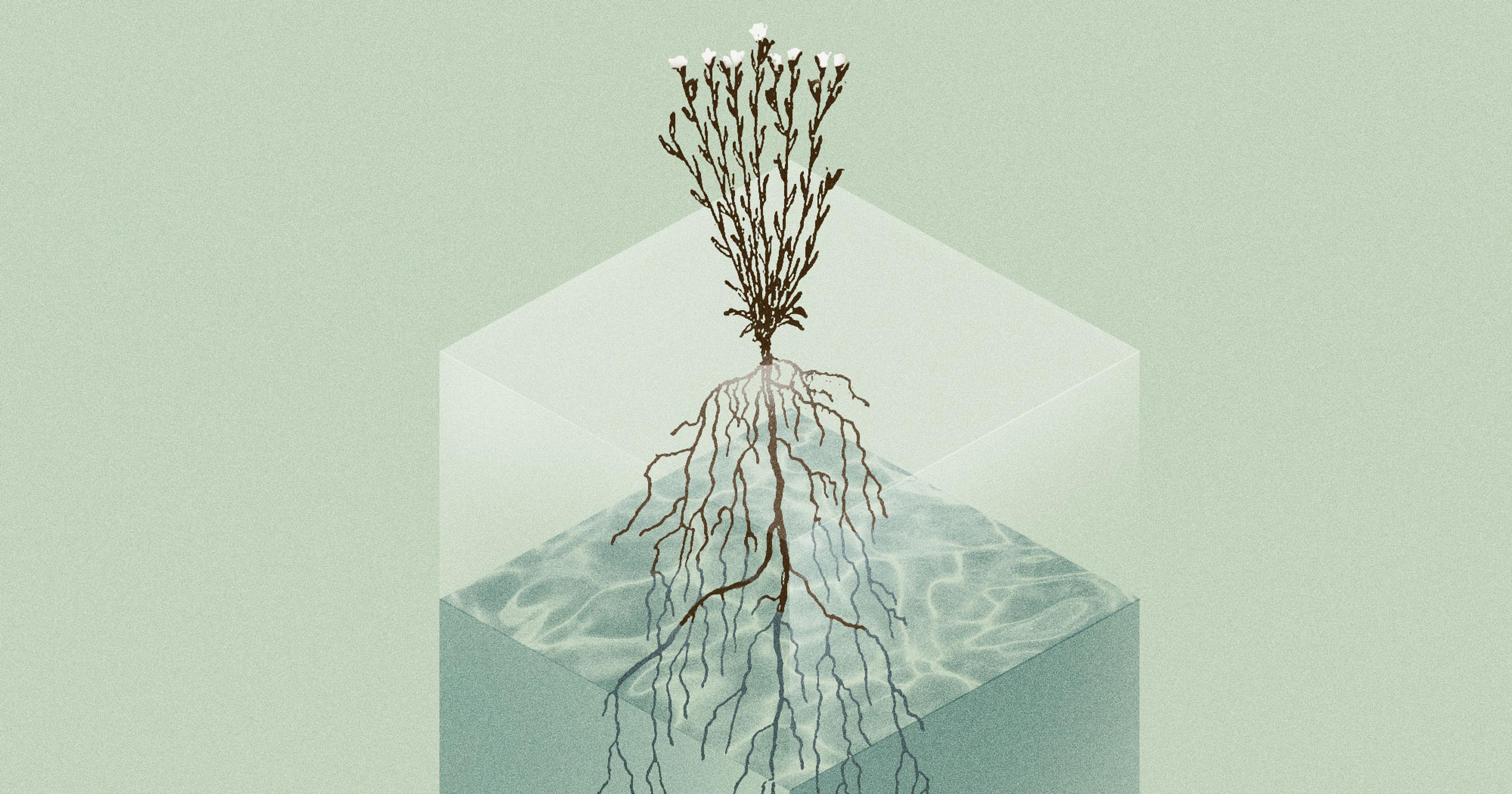

In 2017, Feng Jiao, a chemist then working at the University of Delaware, started to think that it didn’t have to be that way. What if carbon dioxide could be converted into a chemical that plants could take up through their roots and then transform into the sugars they need to grow, rather than relying on photosynthesis to do the same thing? A few years later, he proved that instead of sunlight, naturally photosynthetic organisms like algae could feed on acetate, a chemical compound that can be made from carbon dioxide using a process called electrolysis.

“If you look at photosynthesis for traditional agriculture — the energy efficiency is only about 1 percent,” said Jiao, who is now at Washington University in St. Louis. “We’re trying to take advantage of these electrochemical systems which can operate at a much higher efficiency. Then we can overcome some of the shortcomings in the nature of photosynthesis.”

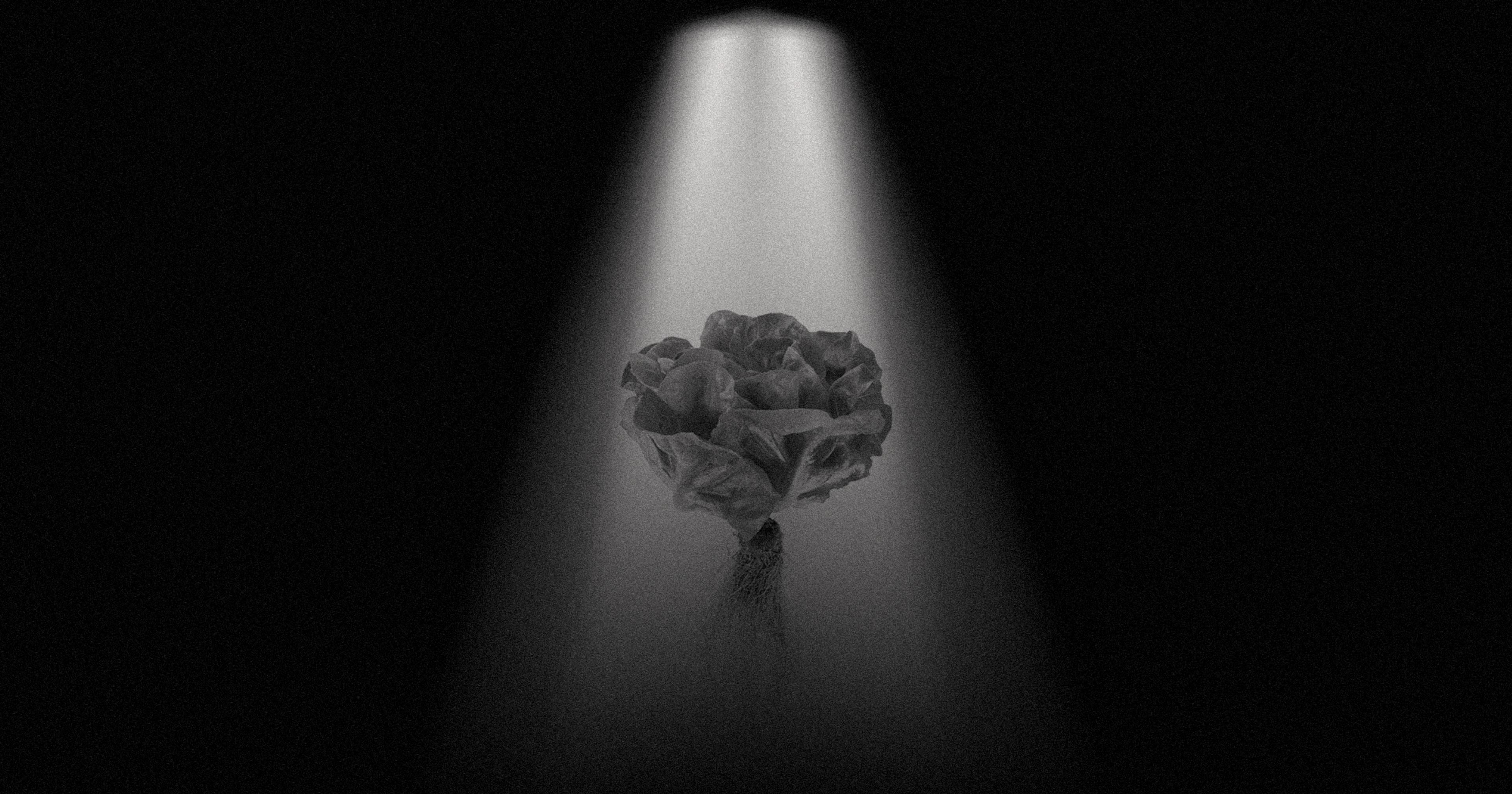

In a paper published in November in the journal Joule, Jiao and Robert Jinkerson, a specialist in artificial photosynthesis at the University of California, Riverside, argued that their system — known as “electro-agriculture” — could convert electricity into chemical energy with four times the efficiency of photosynthesis. So far, they’ve been able to grow algae, yeast, and mushrooms in complete darkness, and are testing out more complex plants like tomatoes and lettuce, which they’re not able to grow entirely without light just yet.

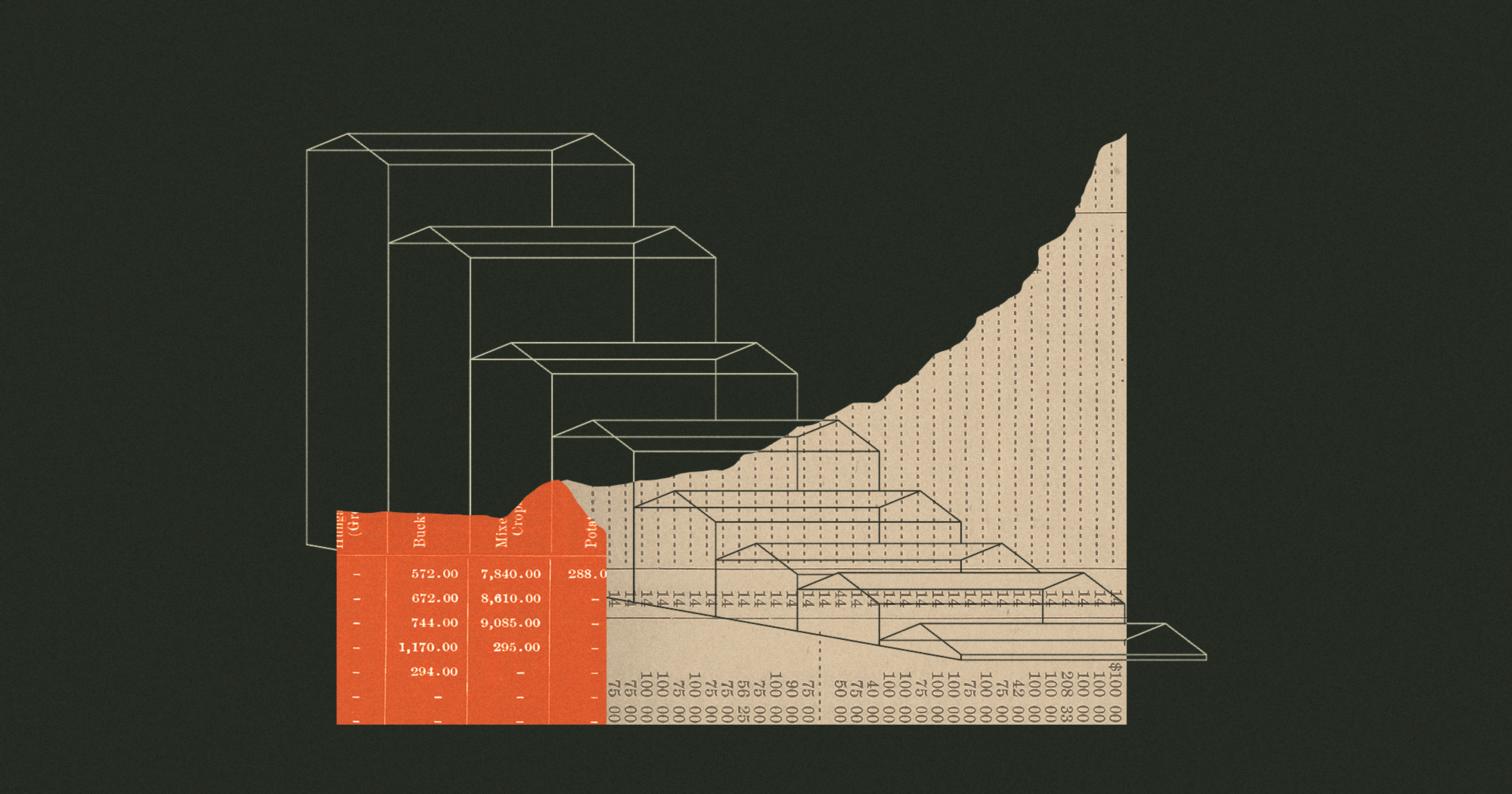

Their goal, the pair argued in the Joule paper, is to demonstrate that indoor vertical farming powered by electro-agriculture can help meet the needs of a growing population while reducing the impact of agriculture — which is responsible for one third of global greenhouse gas emissions — and make it more resilient in the face of climate change. Producing the entire U.S. food supply through electro-agriculture, Jiao and Jinkerson wrote, would reduce land usage by 88 percent.

Jiao is quick to admit, though, that practical concerns make upending the entire U.S. food system unrealistic. Aside from the massive infrastructure buildout required to support the energy drain, vegetables and leafy greens would likely have to be genetically modified to accept acetate, a shift that Jiao thinks could be difficult for the public to accept given the entrenched movement against genetically modified organisms.

Consumers also might find the very concept of a plant grown without sunlight to be off-putting, though Jiao said that these fears could be put to rest once it’s made clear that the crops don’t look or taste any different. He harvested the mushrooms he grew in his lab using acetate, and said that their flavor didn’t differ substantially from the ones he buys from the grocery store. “I thought it would taste like vinegar, but it doesn’t,” Jiao said.

Even if Jinkerson and Jiao are able to perfect the process of electro-agriculture for food crops, taking it from the lab to the farm requires building a whole new kind of enterprise. So far, Square Roots, the vertical farming company co-founded by Kimbal Musk — brother of Tesla’s Elon — is the only producer working toward commercialization. With funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Square Roots dedicated one of its farms in Grand Rapids, Michigan, to testing out the electro-agriculture method developed by Jinkerson and Jiao. The company is trying to understand whether and how this technique could be applied to grow crops on a larger scale, said Square Roots’ head of innovation and partnerships, John Paul Boukis.

“Electro-agriculture can ... bring consistent food production to places that historically rely on importing food at a very high cost and with a large carbon footprint.”

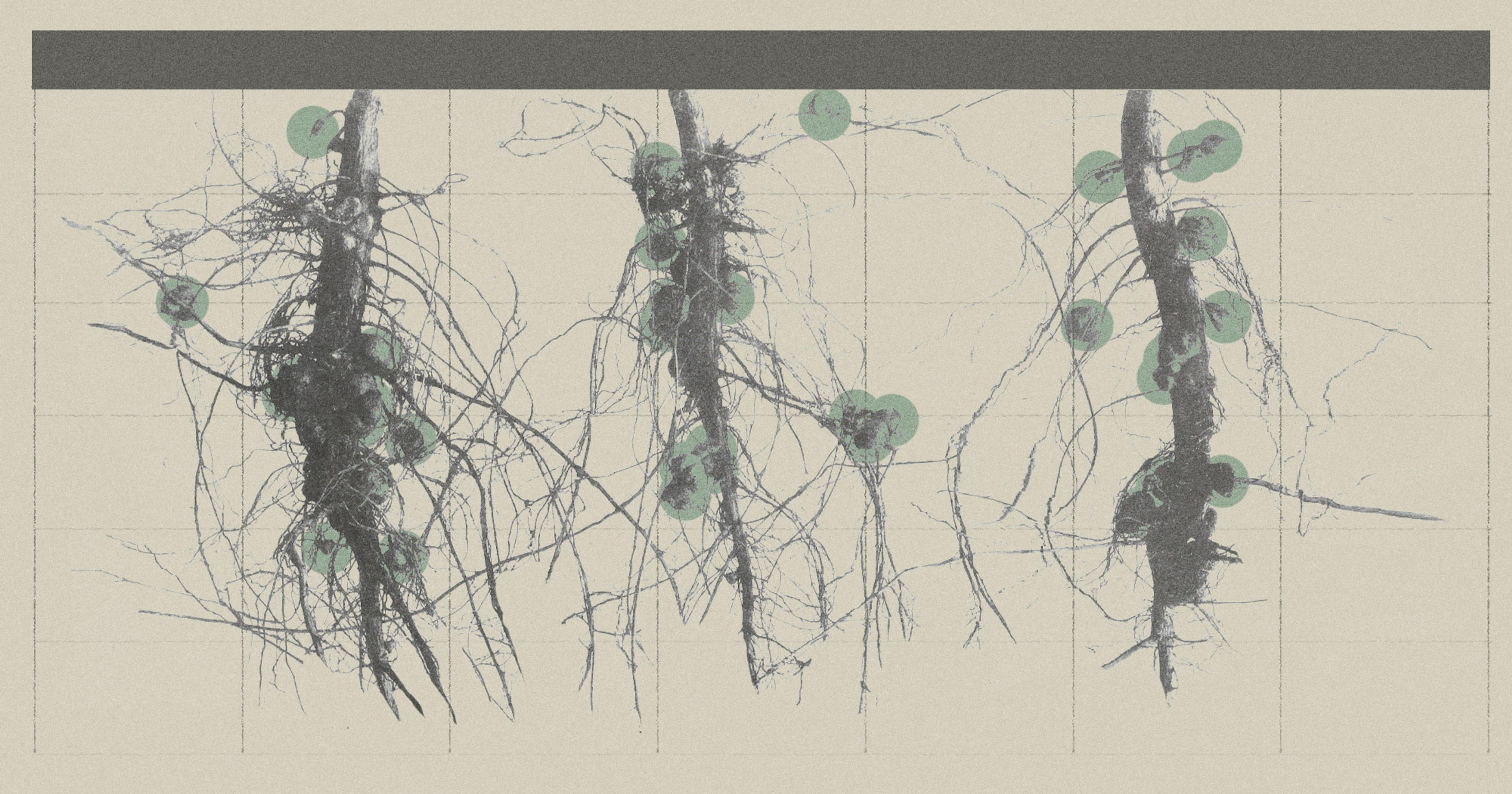

So far they’ve grown arabidopsis, a “model” plant that’s used to get a quick read on the effects of an experiment because of its fast life cycle, as well as tobacco, which provides a better idea of what it might be like to grow leafy greens. Though they’re still in the research & development phase, Boukis said that early observations have been promising; the tobacco plants grown using acetate and reduced light look about the same as they would in a field outside.

None of the plants currently being grown by Square Roots will be sold to consumers, and getting there could take years, if it ever does. But Boukis has high hopes for electro-agriculture as a way to address the economic problems that have beset the vertical farming industry as a whole. After promising to revolutionize farming and solve the climate crisis, a string of early investments from the likes of Jeff Bezos and Alphabet’s Eric Schmidt spurred an indoor farming boom. But with the initial hype dying down, multiple operations have folded in recent years, in part due to the massive amounts of electricity required to power their operations. Square Roots has also downsized, laying off most of its staff and closing all but one location in 2023.

But theoretically, if plants could be grown in the dark, vertical farms wouldn’t have to run LED lights 24/7, instead powering their acetate production using a smaller amount of electricity derived from solar panels.

“While electro-agriculture is still early in its development, it could become instrumental in reducing the lighting energy required for indoor farming, bringing down costs and removing carbon,” Boukis said. “We have high hopes for this technology to make indoor farming more viable, especially for low- and middle-income countries disproportionately affected by climate change disruption.”

But while the research on electro-agriculture touts its efficiency compared to plants grown using sunlight, there are ways to make photosynthesis more efficient without relying on solar panels, which themselves require a high energy input, said Amanda Cavanagh, a plant scientist at the University of Essex in the UK. Her research focuses on genetically modifying crops to avoid wasting energy while converting sunlight into sugars, a process that, while not 100% efficient, is still what she believes is our best option.

“I think it’s foolish to think that there’s only one way to produce food.”

However, Cavanagh doesn’t discount the potential of electro-agriculture altogether. “I think it’s foolish to think that there’s only one way to produce food,” she said, adding that she believes it could support more localized food production in places that aren’t able to farm outside because of harsh or unpredictable weather, like the Canadian Arctic or desert nations like Saudi Arabia. The U.S. government is also interested in using electro-agriculture to grow food in outer space. “Vertical farming or electro-agriculture can find their niche in those areas and bring consistent food production to places that historically rely on importing food at a very high cost and with a large carbon footprint,” Cavanagh said.

Still, she doesn’t think growing plants on acetate will ever be a realistic pathway to rewilding large swathes of agricultural land. Most U.S. farmland is either used for animal pasture or dedicated to growing commodity crops like soybeans, wheat, and corn, which can’t yet be grown indoors on a large scale. Fruits and vegetables only make up about 2 percent of U.S. farmland. And although leafy greens and specialty vegetables are better suited to an indoor growing environment, even the Square Roots team hasn’t yet figured out how to grow those completely without sunlight.

“Plants cannot currently be grown to harvest on acetate or in the dark, and achieving either or both is an absolutely massive challenge,” said Emma Kovak, food and agriculture analyst at the Breakthrough Institute, a sometimes-controversial think tank that studies how emerging technologies can help address major challenges like climate change. She believes it’s worthwhile to continue research into electro-agriculture for the chance that it could help scientists learn how to grow food in hyper-specific environments, such as during space travel. But she doesn’t believe it’ll ever make up a “significant component” of crop production here on earth.

“For all the talk of photosynthetic inefficiency, when crops are grown outdoors, sunlight is a free and abundant energy source,” Kovak said. “And that’s hard to beat.”