The construction and manufacturing industries have increasingly turned to labor-saving mechanical exoskeletons — farming may be the next frontier.

At risk of stating the obvious, farming is physically challenging work that takes a toll on the human body. Over the years, we have turned to various forms of technology to amplify the efforts of a single person, starting with a single plow behind a mule or ox, progressing to a motorized tractor, 700+ horsepower combine harvesters, and now robotic weeders and autonomous flying drones that handle a range of tasks. But what about the human body? Is it destined simply to be replaced by machines?

The fact is that people remain a weak link in modern farming. According to some sources, agriculture is considered the most hazardous occupation globally. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) accounting for 93% of occupational injuries. And of these, lower-back pain is the most frequent, with shoulder injuries coming in second.

Exoskeletons for the Assist

Exoskeletons are devices that are worn on the body to augment the natural capabilities of a human worker. Once confined to the world of science fiction — who can forget Ripley’s exoskeleton-enhanced final battle in the movie “Aliens” — these have now become practical for use in many industries. There are two major categories of “exos” (as they are known in the industry): powered and passive.

Powered exos use motors to provide additional force for certain actions, such as lifting objects or wielding heavy tools overhead. These tend to be complex — and expensive — bits of machinery that require recharging and regular maintenance. While these may be suited for specific manufacturing tasks, they are typically beyond what farmers typically need or can afford for the foreseeable future.

Passive exos are the other class of devices. These take the energy created from one motion — such as bending over — and then release that energy to the wearer for the opposite motion, such as lifting an item from the ground to waist level.

These passive devices do not require the expensive motors, wiring, batteries, and sensors found in powered exos. Instead, they use a variety of materials to store and release energy: springs, torsion bars, gas pistons, elastic bands, and flexible beams. Some designs rely on a rigid frame while others are made from fabric and other flexible materials. According to some sources, current passive exos can cost from $2,500 to more than $14,000, depending on design and which parts of the body are supported.

Designs vary based on the type of targeted task. For example, lifting boxes of produce could require one sort of assistance, while reaching overhead to harvest fruit could require something different. But can they actually help farmers and farmworkers?

The Benefits

Many studies have shown clear benefits from wearing exos in other industries such as warehouse work and manufacturing. According to Karl Zelik, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Vanderbilt University, one longitudinal study of warehouse workers tracked more than 281,000 hours of work while wearing exos. Historical data would predict 10.5 back strain injuries over that period, but the study revealed that there were none.

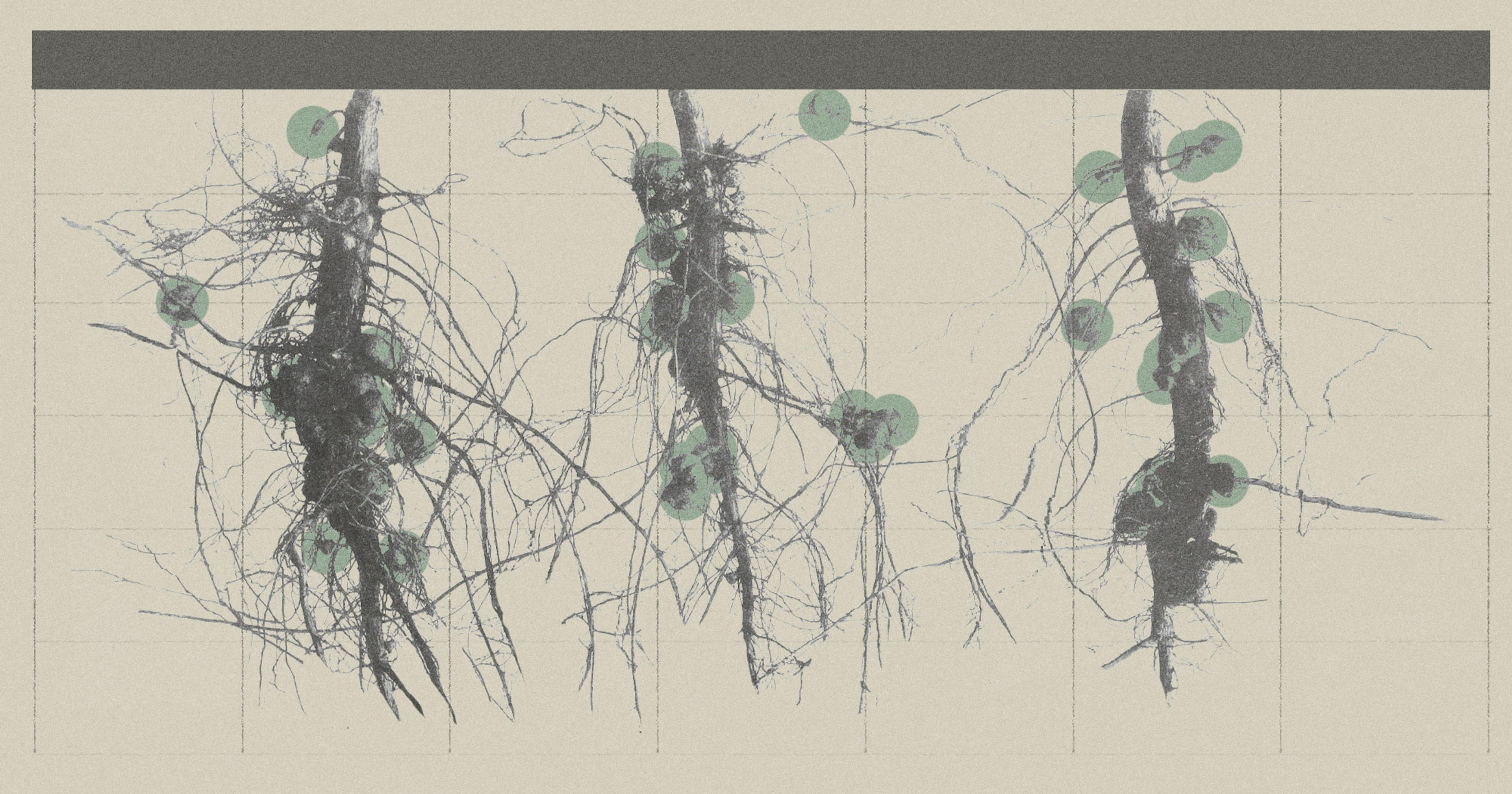

Not as much research has been done in farm settings, but the existing studies point to clear benefits. For example, one test of an upper limb exo in orchard management tasks reduced muscle activity by up to 40%. Reduced muscle activity results in less fatigue and strain, which in turn lowers the risk of injury.

Another study gave a back support exo to farmers for their daily operations and several of the subjects cited increased productivity by reducing fatigue. Many of the subjects also reported feeling more protected when shoveling. In some cases, the exo helped them maintain proper posture when lifting, which can reduce the risk of lower back injuries.

Sarah Ballini-Ross is co-owner of Rossallini Farm in Oregon; she and her husband sometimes use exoskeletons in the work on their diversified operation. She is also an expert in exo technology and founder of Evolving Innovation, a consulting firm that provides safety technology and ergonomic solutions services. Ballini-Ross said that fatigue reduction is an important factor in their use of exos. “A lot of the farmwork really involves that repetitive lifting from ground to waist level, so my exo is the first thing I grab when it comes to doing hay.” Other tasks where she wears it is “on inventory days when we unload a couple of tons of 50- to 70-pound boxes.”

Not a Cure-All

In spite of the benefits, exos are not the solution for every case. Not all passive exos are the same, and each has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Some exos can restrict movement to enforce proper lifting posture, which can reduce injury. However, other designs might not have this feature, which means that the worker could place themselves in an awkward or dangerous position that could lead to injury.

For example, the same feature that enforces proper posture when lifting might restrict movement that requires rotating the body, such as when shoveling. A warehouse worker is likely to do a similar task over and over all day, but a farmworker often has to rapidly switch from one task to another.

Even passive exos can be bulky and awkward to maneuver in during daily activities. Farmers in one study cited the fact that they can make it difficult to get in and out of the cab of tractors and other farm machinery. And having to take the exo on and off throughout the day can take up significant time.

Most passive exos have at least some fabric, but this fabric can get soiled — especially from sweat on hot days or during strenuous activities — which can make them unpleasant to wear. Most also include Velcro-style hook-and-loop fasteners. These fasteners make it easy to adjust the fit of the device for workers of different sizes, and to accommodate the presence of layers of clothing. But those hooks and loops can also grab foreign materials, impairing their functionality and appearance.

Ballini-Ross noted, “I use my exo when trimming the hooves of our sheep, and hair and straw gets stuck in the fabric. So when I take my exo to a presentation or a conference, I have to think twice because maybe I’m bringing a little too much of the farm with me.”

Obstacles to Adoption

Education may be the biggest barrier to more widespread adoption of exos in agriculture; many farmers simply aren’t aware of the products and their potential benefits.

Close behind comes the question of expense. Even passive exos can be costly, and unlike heavy farm equipment, the manufacturers are not set up to provide payment plans or other terms to ease the financial strain.

But the problems go beyond those two obvious factors. For example, many farms rely on a transient workforce. A small farm does not have the resources to stock a full range of exos to meet the needs of different body sizes. Furthermore, different tasks could require different exo designs. Harvesting or weeding some low-growing crops require bending and stooping, which needs a different type of support than lifting boxes of produce or shoveling.

In addition, a farmworker’s needs vary with the season. Providing exos for these workers for just a week or two may not be feasible.

Another part of the problem is that the exo industry has not yet focused on the needs of agricultural workers. The low-hanging fruit is in other industries, such as warehouse logistics, construction, and manufacturing. These applications have narrowly defined tasks with lots of repetition, and often involve large corporations with the capital to invest in new technology.

To really be embraced in agriculture, exo manufacturers would need to create exos that are modified for farm work. For example, one study found that a typical exo requires adjustable straps that go around the thighs. This design blocks access to pants pockets where farmworkers keep tools such as pruning clippers where they can reach them easily. But with little demand for agricultural exos, companies have little financial incentive to design around these problems.

While exoskeletons have proven their value in terms of reducing workloads and related injuries for some farming tasks, significant obstacles remain. But as farmers become more aware of the benefits, as the costs continue to come down, and as manufacturers respond more to the specific needs of agricultural tasks, we can likely expect to see more exos down on the farm.