Learning how not to farm from hydroponic millionaires.

It seemed almost every morning started with a flood of hydroponic solution. Within minutes of arriving, we’d haul out the troop of wet-dry vacuums and get to work sucking up gallons of spilled liquid. The smell of synthetic nitrogen permeated the trapped air of the indoor farm and stuck to the bottom of our shoes. The flooring was getting ruined.

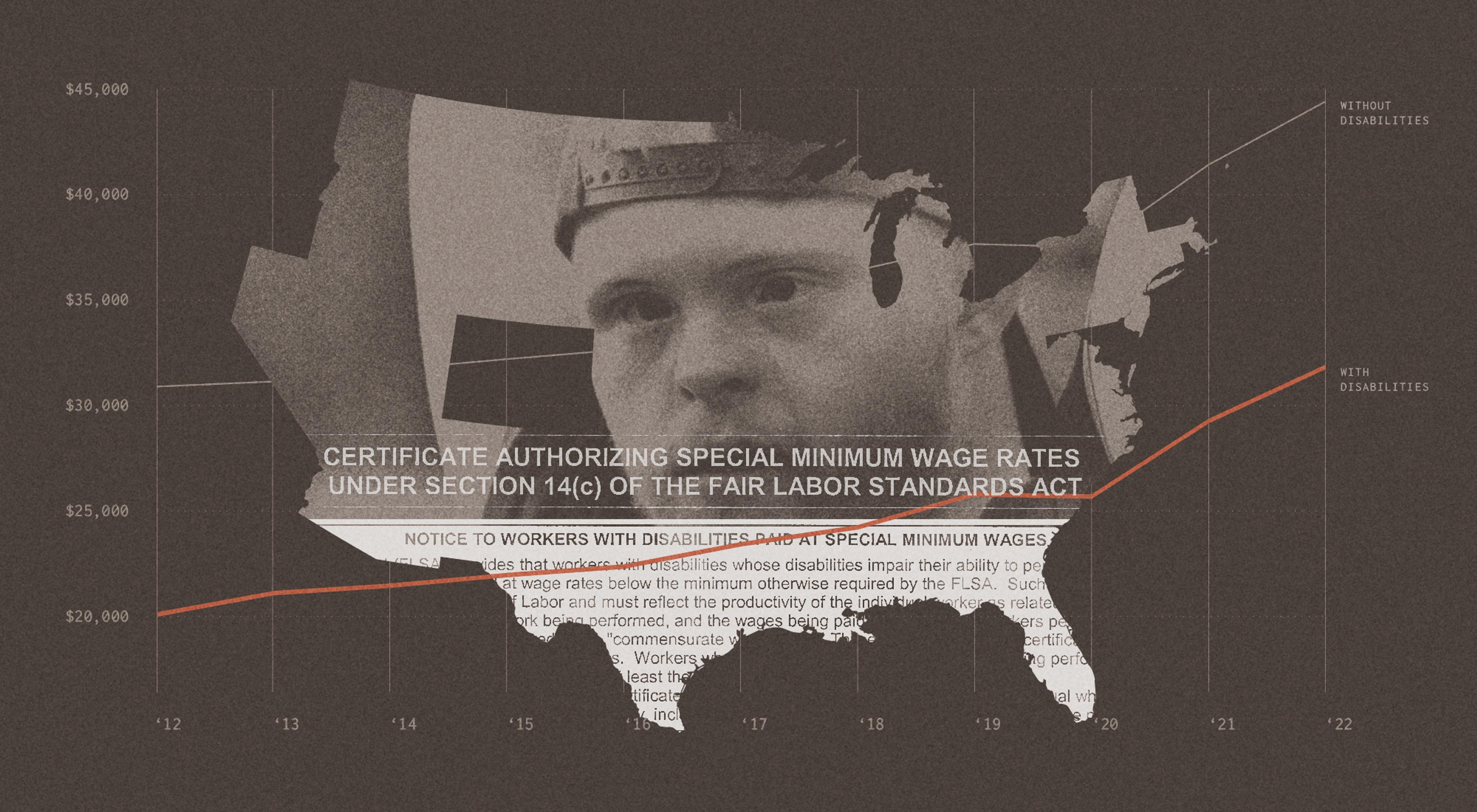

The indoor farm, specializing in lettuce and microgreens, had gotten off the ground a year before I started, when a wealthy father and son dumped millions into renovating the large basement of a luxury apartment complex in North Philadelphia. Hundreds of utility racks were moved in, each equipped with the company’s custom ebb-and-flow grow system. Full-spectrum LED lights were installed throughout, their purplish glow washing over pipes and plants with eerie luminescence.

Conveniently, the son lived upstairs in one of the building’s units, which made for an unbeatable commute. On a typical morning, he’d take the elevator down to the grow space, wearing flip-flops and socks (not great for wading through hydroponic puddles), instruct us to vacuum up the mess, then retreat to his office.

I’d always heard about the grinding difficulties for startup founders. While this mythos is over-hyped, there is often truth to the urgency that motivates early entrepreneurs. Capital can be hard to secure, cashflow is tight, and everything balances on a tightrope during those early days. For our boss, the situation was a little different. The main challenge he seemed to face was the capacity to do anything. After floating around between a handful of undergrad programs, he had finally finished with a degree in vocational development. His graduation present? A hydroponic operation.

A $1.5 million hydroponic operation.

My stint at the basement farm started in June 2020, just as Covid was reaching a crescendo. Sure, maybe it was not the best time to push a year-old capital-intensive ag startup toward profitability. But, there were exceptions, winners in the food scene who had risen to the top over the last few months of shakeup. I hoped we might be one of those rare pandemic success stories.

Our founders came to us one morning with a pitch. The father was down from New Jersey on one of his regular drop-ins. Although his son had been entrusted with most of the day-to-day operations, it was dad’s money. We could expect his visits — some announced, some unannounced — once or twice a week.

We gathered in the main office. There were five of us in the room, including the two founders. They may have been loose with money for tech gadgets (air purifiers stationed every ten feet, a state of the art reverse osmosis machine), but they were frugal on the labor front. It was a lean crew.

Sales were down. Our two flagship crops, high-end lettuce and microgreens, were not moving. Restaurants had switched to takeout menus, and chefs were looking to cut down on ingredient costs as their already-tight margins faced a serious squeeze. The father had our answer. With a crazed look in his eyes, he leapt up on the table. Well into his sixties, he was remarkably fit. He picked up a dry erase marker and scrawled in bold letters on the whiteboard: “MICROGREEN POWDER.” I took out my phone and grabbed a quick picture of this history-making moment.

Luke Carneal

·The microgreen powder lab

A dehydrator was purchased, and we were directed to reserve our next crop of microgreens for the oven.

The thinking was simple. If our main challenge had been keeping consistent inventory of perishables, moving in the direction of shelf-stable items could give us the wiggle room we needed when demand periodically flagged and yields were under target. The closer we got to dealing in units rather than pesky plants, the better.

The father had found success in business back in the eighties, not in agriculture, but in hardware. Like tools, nuts, and bolts, he wanted to move parts. This was the first farm boss I’d worked for who insisted that we assign SKU numbers to every one of our products before it could be sold.

At first, I welcomed this commitment to organization. My experience on other farms had often been a flurry of business transactions — hundreds of varieties of vegetables coming off the field, some sold at market, some reserved for the CSA, others heading to local restaurants. While I loved this cacophony, I wanted to experience a lean operation, the kind of farm Ben Hartman has written about so convincingly.

In a dark corner of the space, we laid out a hundred nursery flats and sowed them with a variety of microgreens. In two weeks, it was time to harvest. After shaving the greens just above where the stems grew out of the hemp substrate, we stuck them in the dehydrator, and set it to cook low and slow for a few hours. When the machine dinged, we pulled them out to find them crispy, flattened down onto the oven’s trays, and sapped of life (although apparently still chock-full of nutrients). What started out as 20 pounds of fresh greens had been reduced to mere ounces. Some quick back-of-the-envelope math told us that we would have to sell a small jar of this dry elixir for many hundreds of dollars to get close to break even. To the credit of our two founders, the idea was scrapped.

We went back to growing microgreens the old-fashioned way and shifted attention to our other workhorse: lettuce. Production had been inconsistent. Some weeks the ebb-and-flow system yielded beautiful heads of romaine, butter, and frilly leaf. Other weeks it gave us weak and stunted plants. One of my coworkers was determined to get to the bottom of the issue, and without the distraction of microgreen powder, he quickly came up with the diagnosis.

For the entire duration of the farm’s existence, the clean and dirty lines had been swapped, bathing the root zones of our plants with adulterated water.

Purified water is crucial to a successful hydroponics operation. The founders knew this when they invested in a premium reverse osmosis machine. This machine takes source water — in this case, Philly’s “hard” city water — and filters out a wide range of dissolved solids. Very slowly, water is pumped out of the RO machine through two lines: one clean, one dirty. The dirty line is meant to feed into a drain, never to be used, while the clean line fills the main holding tank.

My coworker’s dark discovery: For the entire duration of the farm’s existence, the lines had been swapped, bathing the root zones of our plants with adulterated water. In hindsight, the healthy crops that we occasionally harvested were almost inexplicable. When the tubes were finally placed in their rightful spots, we could almost see the lettuce let out a sigh of relief.

Microgreen powder had been a bust, but lettuce was back on track, and the father got to work courting local wholesale distributors. What he lacked in agricultural knowledge, he made up for with charisma that read as smarm to us employees, but to his associates gave off a welcoming confidence.

Around this time, the son went away on a four-week sabbatical to gather his thoughts and draw up a game plan for the struggling company. In his absence, daily operations were delegated to me and my two coworkers. Not wanting to leave us unsupervised, cameras were installed throughout. We kept shit-talking to a minimum until we were off the premises.

One midnight, we got a text from the father. “It looks like someone might be breaking into the farm. I noticed some weird activity on one of the cameras near the RO machine. Can one of you go and check on things?” Ordinarily, his son, sleeping upstairs in his apartment, would have been sent to take care of something like this. But he was in a cabin in the Catskills.

My coworker who lived closest to the farm volunteered to go. After an hour, he sent a text letting us know that everything looked fine. The next day, I approached him, “What was that about?” I asked. His face looked tired; he couldn’t have gotten more than a few hours of sleep. “Sweat test,” he said, “it was nothing more than a sweat test.” Our perceived loyalty was on the line.

The two most elemental parts of a farm were missing all along: consistently well-grown plants and a customer base trained to buy them.

The father was anxious. He’d landed a meet-and-greet with one of the oldest Italian produce wholesalers in the city. They were scheduled to tour the farm in three weeks. Sold on promises of bountiful greens and fresh herbs, we had limited time to bring reality up to speed.

We went on a seeding spree. Time was not on our side. No amount of good water would get these plants to grow fast enough to be anything much to look at in 21 days. When we tried to explain this, we were told to press forward. It had been difficult to clinch a visit from these kingpins of Philly produce, and we were not going to let the opportunity slide.

Soon enough, the day came. Eight people arrived in a company Sprinter van at seven in the morning. Produce workers are practically nocturnal, with days starting only a couple hours after midnight. A family business, the crew was jocular and spoke with loud Philly accents, a fun match to our boss’s South Jersey vernacular. They kept a good attitude throughout the tour, asking follow-up questions to our pitch, peering in to look at the crops — some having only just germinated.

In something of a grand finale, the son made an appearance about halfway through the meet-and-greet, returning from his month-long stay in the woods of Upstate New York. Not one to over-dress, it still surprised me to see that he chose flip flops for the big meeting. In a clear imitation of his dad’s natural salesmanship, he schmoozed and mingled, speaking confidently about the many crops on display (the great majority of which he had never before seen until that moment).

We got a call from the produce company a few days later. They’d taken time to think it over. While they saw potential in our thousands of baby seedlings, they had decided we weren’t a good fit. From that point on, the mood around the farm turned sour. The father could not have been happy with his $1,500,000 investment, and the son seemed to come back from his retreat unreplenished and pessimistic. We were directed to slow down our seeding, and to instead devote most of our time to a thorough cataloging of every seed, every different hydroponic substrate we had trialed, every piece of equipment scattered throughout the cavernous basement.

When I joined the farm, it was in its enterprising startup phase. It was now in its cost-recouping phase. When the inventory exercise was complete, we were thanked for our efforts and asked to turn over our keys.

It had turned out that, despite the barcode machine, the delivery system set up to ship microgreen powder overnight and nationwide, and a business reputation that could land us a meeting with a powerhouse produce wholesaler, the two most elemental parts of a farm were missing all along: consistently well-grown plants and a customer base trained to buy them.

“Build it and they will come,” I’d always heard. The cliche did not, in this instance, hold true. I’d never before worked at a farm filled with so much fixed infrastructure — lights, reservoir tanks, pumps. And yet, with only a small section planted out, the massive basement almost always felt empty.