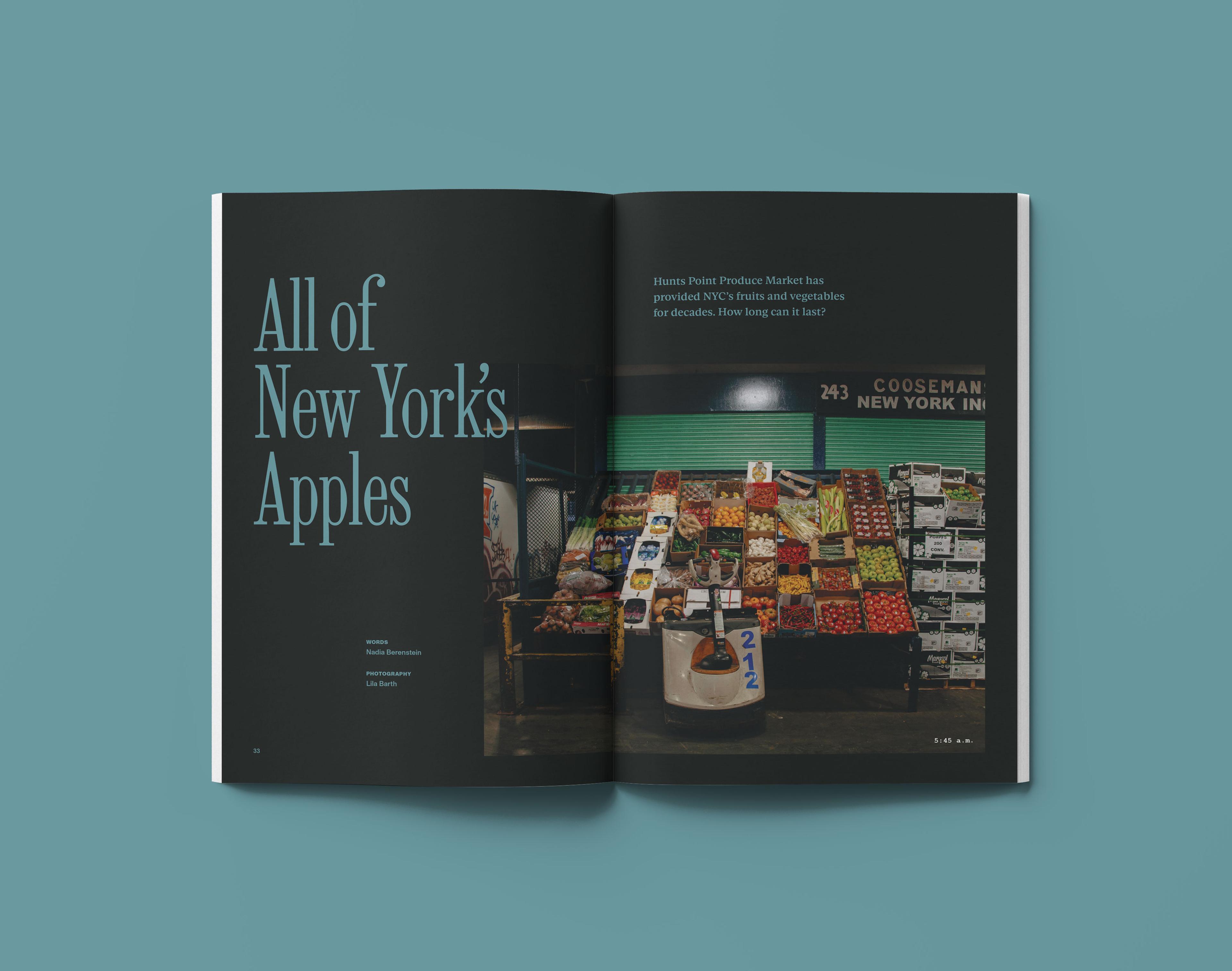

Hunts Point Produce Market has provided NYC’s fruits and vegetables for decades. But how long can it last?

On a map, the New York City Produce Terminal Market resembles the four tines of a fork, angling toward the single-strand Bronx River as though ready to swirl it up like a loose noodle. Glimpsed through the chain link fence on Halleck Street at around 10 a.m. on a Monday in June, it looks like a vast, slumbering truck depot, or some sort of light industrial facility.

This quartet of low-slung buildings is so drab, so unremarkable, so anti-monumental, that you’d be forgiven for heading right past it without a second glance. But within these unassuming structures, a vast hoard of fresh fruits and vegetables sit in chilled rooms, waiting until nightfall, when they will be dispersed among the city’s tens of thousands of grocery stores and restaurants.

Trailers line the decks of the New York Terminal Produce Market at dawn, the end of the market day.

The market — everyone here calls it “the market” or just “Hunts Point” — is the first stop for much of the produce that is bought, sold, and eaten in New York City. By some accounts, it’s the largest wholesale produce market in the world, supplying nearly two-thirds of the fresh fruits and vegetables consumed in the five boroughs. More than two billion pounds of produce, from across the U.S. and 55 other countries, are bought and sold here every year. The bargain-priced blackberries at your bodega; the nopales and epazote at a Mexican grocery in Queens; the scarlet-speckled Castelfranco chicory in the salad you order at a bougie pizza place — all likely passed through the market, sold by one of 30 or so wholesalers in the million-square-foot facility.

The produce market is the culmination of a vision for public markets that was born in the 19th century and realized in the 20th. These markets represented an aspirational commitment by civic leaders to make fresh food accessible and affordable for urban residents. Along the way, wholesale terminal markets — so called because they were integrated with railway terminals — helped invent the modern food system. They became critical hubs in the infrastructure of abundance, mobilizing national and global supply chains dedicated to satisfying our appetites, regardless of the seasons, for better or for worse.

New York City Mayor Robert Wagner and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman look at an architect’s drawing of the new Hunts Point Market during groundbreaking ceremonies in the Bronx in 1962.

·Image from Library of Congress

The market is also, in many ways, a relic. When it opened in May 1967, the publicly financed facilities were state-of-the-art, and a huge leap forward from the shambling, traffic-clogged marketplace that persisted in downtown Manhattan for more than a century. But now, nearly six decades later, the market’s infrastructure is creakily out of date, with consequences for the wholesalers who do business there, the stores and consumers who depend on them, and the residents of Hunts Point.

Hunts Point is no longer the necessary institution that it once was. National food retailers like Whole Foods, Costco, and Wegmans largely sidestep the terminal market, maintaining their own distribution centers and warehouses. Other large supermarkets and restaurant chains are supplied by private companies with their own distribution centers (think Sysco, or US Foods).

But for independent grocers and restaurants, and large-volume buyers like the school system and the city’s jails, Hunts Point is irreplaceable. “If the market went away, probably most of the small businesses — especially the small grocers in New York City — would also vanish, because they can’t buy their produce in the bulk orders that a food distributor requires,” Karen Karp, founder of an eponymous consultancy specializing in food systems innovation, told me.

As the market embarks on a campaign to rebuild — the price tag on necessary upgrades and a hoped-for expansion runs upwards of $600 million, about half of which has already been pledged by federal, state, and city officials — it’s worth considering how Hunts Point came to be the reservoir for New York City’s fresh food, and what its future may hold.

“The Variety of Fruits and Vegetables Will Astonish”

The produce market is the original, and the largest, tenant in New York City’s dedicated Food Distribution Center (FDC), a 300-plus-acre zone in Hunts Point, a stubby peninsula in the South Bronx. The FDC includes both public markets — the wholesale meat market and the New Fulton Fish Market — and private enterprises such as restaurant supplier Baldor and an Anheuser-Busch warehouse.

Historian Helen Tangires has called terminal markets “the gated communities of the food trade.” Despite their key role in the economic and gastronomic life of cities, these semi-industrial sites — usually located far from downtown areas, operating at night and selling in wholesale volumes — are easy for ordinary eaters to overlook.

This wasn’t always the case. For much of American history, municipal laws restricted where food could be sold, and who could do the selling. In early America, the market was literally a farmer’s market — places set aside for producers to sell directly to consumers. Wholesalers and other middlemen were regarded with suspicion, as agents who increased the price of food and profited at the expense of ordinary citizens.

Produce Exchange

·Image from Library of Congress

As cities grew, so did the volume of perishable food moving in. “It was a logjam,” Tangires told me. “You needed a process to redistribute it and get it to other places. Cities found they couldn’t solve this problem alone.” New York and other cities ultimately relaxed some of their restrictions. Food wholesaling and distribution became economic sectors.

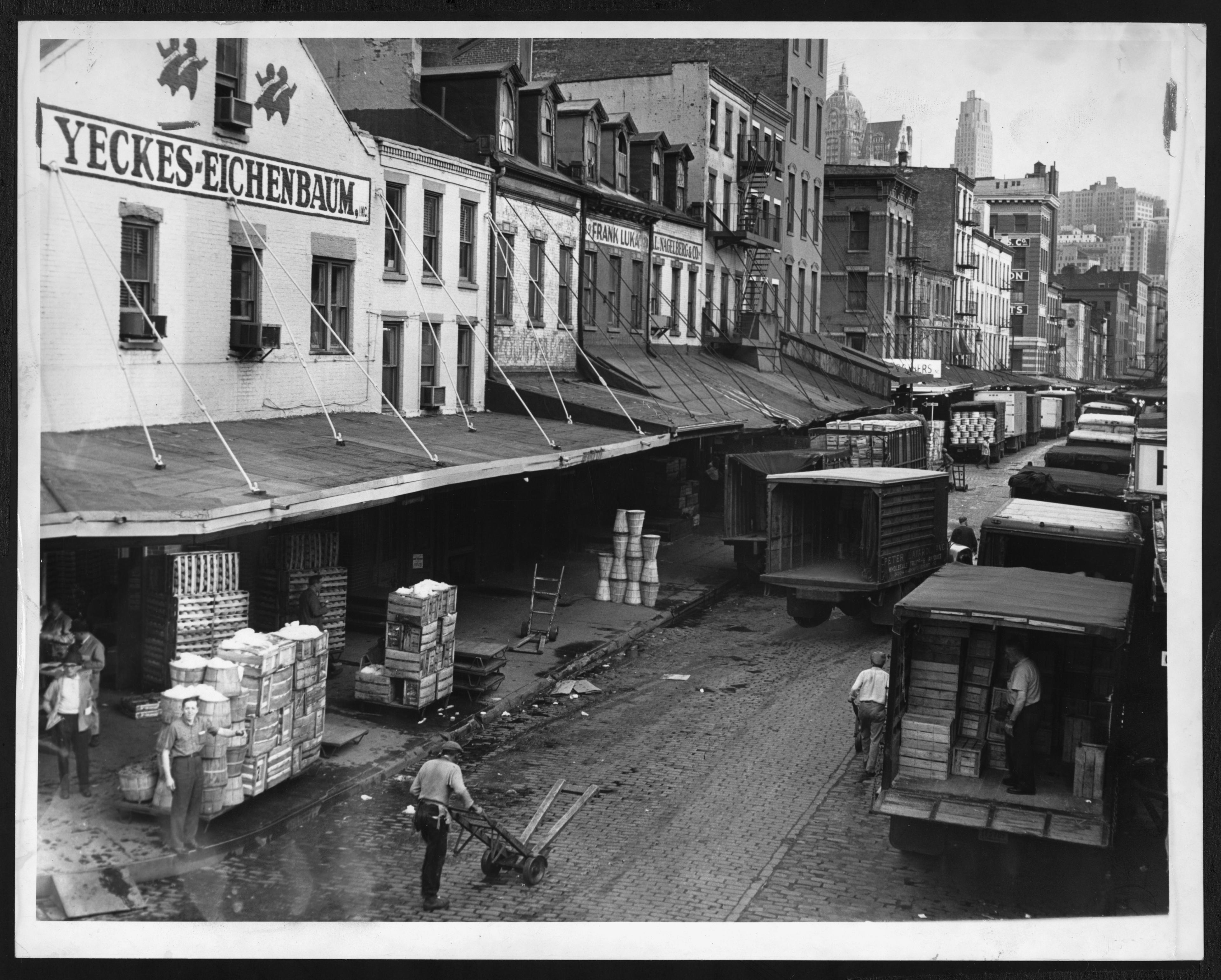

Wholesale and retail public food markets stretched across Manhattan’s lower west side in the 19th century. Slaughterhouses and meat markets defined what became known as the Meatpacking District, and fish and seafood were sold south on Fulton Street. Washington Market, in what is now the financial district, was the hub for fruit and vegetable wholesalers. In the 1880s, as many as four thousand farm wagons arrived each day, choking surrounding streets with traffic.

Produce Exchange

·Image from Library of Congress

The result was squalor, disorder, and disarray — but also abundance, novelty, and deliciousness. “There are no markets in the world equal to the markets of this City,” pronounced The New York Times in 1879. If a visitor could only look past the filth and clamor, “the variety of fruits and vegetables will astonish him ... At all seasons he will find a variety of vegetables unknown to any other market in the world, and find them, too, months in advance of their regular seasons.” Wholesalers masterminded this flow of goods — buying tomatoes from Bermuda in early February, and from Southern farms in the spring, until local crops came in — weaving a continuous supply of tomatoes stretching from late winter to summer’s end. They were not simply feeding the city’s residents. They were stretching the apparent limits of the seasons, and reshaping urban appetites to crave fresh food from distant places.

Trucks being loaded with produce at Washington Market

·Image from Library of Congress

These changes accelerated with the introduction of the refrigerated railcar and frigid, temperature-controlled warehouses, links in the robust network of chill that we now know as the cold chain. This is when public markets started to be re-envisioned as terminal markets — fully integrated with railway terminals, and linked to the network of rails fanning out across the continent. In 1929, Walter Hedden, former head of the New York Port Authority, calculated that fruits and vegetables noshed by New Yorkers traveled an average of 1,500 miles. Increasingly, food consumed in the city meant food from far away.

As the city’s hungers outgrew the capacities of the region’s farms, the market also outgrew its downtown location. For decades, city planners had pleaded for a modern, dedicated, and centralized hub that could efficiently distribute food across the city and its suburbs. As land values in Manhattan spiked, city power brokers wanted the market out. Officials had a city-owned site in the South Bronx in mind: Hunts Point.

“It’s Always Good Morning at the Market”

As I tried to understand the market and how it works, it became clear that visiting during the day would never give a full picture. The logistics of large-scale food distribution require a topsy-turvy schedule, laboring through the night in order to restock stores before they open for business. The vision of abundance we enjoy during our waking hours is maintained by workers and truckers hauling produce while we sleep.

“It’s an adrenaline rush,” Matthew D’Arrigo, CEO of D’Arrigo New York, one of the market’s largest wholesalers, told me. “It’s a very different world here at night than it is during the day.”

“We can’t wait. We can’t stop. We can’t hold on to stuff too long. As soon as it’s picked, it starts to die.”

During the day, the market resembles a warehouse. By night, it’s revealed to be a way station, a place where fresh food pauses on its journey. Being in the perishables business means keeping things moving.

Stefanie Katzman is executive vice president at S. Katzman Produce, started by her great-grandfather. “We can’t wait. We can’t stop. We can’t hold on to stuff too long.” She lays down the tragic truth at the center of this business: “As soon as it’s picked, it starts to die.”

I arrive at the market just before four in the morning. The June night is clear, a few stars barely visible in the washed-out urban sky.

The market is a 24-hour operation, but it's busiest in the middle of the night.

I meet Phillip Grant, the produce market’s general manager and CEO since 2019, and his deputy and finance manager, Alex Gomez. Grant — who came to the market after a decade at the New York City Economic Development Corporation, essentially the market’s landlord — radiates competence and political acumen. Gomez, a native of the Bronx, is more subdued, with a nerdy charisma and a deep knowledge of operations. Both look remarkably crisp and alert, belying the dismally late hour.

Four a.m. Tuesday night — make that Wednesday morning — is the tail end of the business day. By daybreak, the line of 18-wheelers streaming into market will have thinned to a trickle, and maintenance crews will be busy sweeping up detritus from the evening’s frenzies: crushed tomatoes, splintered pallets, discarded water bottles.

The platforms hum with activity, as workers haul thousands of pounds of perishable produce while wholesale buyers examine the goods and negotiate their prices.

A grinning man buzzes by on a yellow HiLo forklift, hauling crates of green cabbage stacked higher than our heads. “Good morning!” he calls out with a wave. We are now on PMT — Produce Market Time — where it’s always good morning, even in the dead of night. “That’s the market for you!” laughs Grant.

The market comprises four long, low buildings — each two stories high and a third of a mile long — evocatively labeled A, B, C, and D. Offices are on the second floor, above the loading platform and cold storage units. On one side of the platform, like suckling piglets at a mama sow, refrigerated trailers are hitched up to the platform; some are waiting to be loaded, some are waiting to be unloaded. Others are used for supplemental cold storage, or for charging forklifts — a symptom of the market’s strained capacity. Across from them on the platform are cold storage units, warehouses of chilling produce.

A variety of packaged produce waits for a forklift to transfer it to its next destination. (R) Crates of fresh corn leave a trail of crushed ice as they are transferred from the trailer of an 18-wheeler to cold storage.

The platform — it couldn’t be much more than 20 feet wide — is where the action happens. As we walk its length, many thousands of pounds of produce of varying perishability criss-cross in front of us, from fragile raspberries and strawberries in plastic clamshells to 50-pound sacks of hardy California walnuts. Workers push pallet jacks loaded high with cardboard boxes of Van Gogh mangoes (“Nature’s Masterpiece”) and Honeyglow pineapples; they drive forklifts bearing crates of fresh corn, leaving a breadcrumb trail of crushed ice.

“C Deck is rocking and rolling!” Grant announces with glee.

On B Deck, I meet Tony LoVerde, an older, gray-haired man in glasses, perusing cartons of romaine.

“Excuse me, are you a customer?” I interrupt his lettuce survey. “A customer?!” he barks in mock indignation. “I’m a complainer!” LoVerde runs a grocery store in Borough Park, Brooklyn: Circus Fruits. He’s been coming to the market for 30 years — every night, or nearly — to stock his store’s shelves for the following day.

Tony LoVerde of Circus Fruits inspects lettuces on B Deck.

I ask him how, among all the bounty of produce around us, he makes his choice. “If I want to buy, my customer wants to buy,” he says. It’s that simple. But the price he pays — and thus the price the shoppers at his store will pay — is not so simple.

Hunts Point is an open price market. Everything is negotiated, and negotiable. This is one of the biggest differences between wholesale public markets and private alternatives. National supermarket chains — the Walmarts and the Safeways — make advance contracts with growers, fixing prices, volumes, and other details, often before the planting season even begins.

Nature doesn’t always play along. Farmers sometimes have a surplus. Retail chains sometimes have a shortfall, or a gap in their supply. In these cases, they turn to terminal markets — to the wholesalers who will find buyers for the farmer’s surplus goods, and locate growers who can fill in a store’s inventory.

But the lifeblood of the market, its core customers, are independent grocers like LoVerde. In a high-rent city like New York, grocery stores often don’t have the square footage to maintain large inventories. The market is here for them, essentially serving as a warehouse, allowing them to restock as needed.

Some buyers — such as street carts or bodegas — may be looking for past-peak goods, priced to move fast. Some may be looking for premium produce, pricey perfect peaches for tiny restaurants and high-end grocers. Others may be looking for specialty items to serve a growing immigrant community. In any case, if they can’t find what they need at one wholesaler, they can try another one on the next platform. The wholesalers, who are organized as a cooperative, maintain a (mostly) friendly competition with each other. “In this market, it’s professional buyer versus a professional seller,” D’Arrigo explained to me. “It’s a hard-bargain market.”

Each vendor displays their produce offerings, enticing a range of customers to purchase.

I ask Anthony Andreani, sales manager at S. Katzman Produce, what it’s like negotiating with buyers. He makes an expansive gesture. “We’re like a married couple,” he says. “We laugh, we joke, we bicker. At the end of the day, they leave happy, we’re happy.” He adds, a bit ruefully: “Some of these customers, I see more than my own wife!”

His father, Mario Andreani, the COO of S. Katzman, is supervising action on the platform from a few feet away. He has been with the company for 37 years. “To be in this business, you’ve got to have heart,” he instructs. “You’ve got to have it here, running through your veins!” I ask him about the changes he’s witnessed in his years here. “We used to get 100 percent of our revenue from customers who came to the market,” he says, with a trace of sadness. “Now it’s more like 60 percent. People call in their order, we deliver.”

This is confirmed by other vendors I speak with in the market. More and more of the orders are transacted by phone. This lessening of the vitality, the hectic energy of the market, feels like a loss.

“There Have Been Fistfights”

The New York Times reporter at the market’s opening day in 1967 interviewed Mark Yeckes, one of more than 100 produce merchants who relocated to the South Bronx. Yeckes, who spent five decades at the old Washington Street Market, is basically panting with excitement at the new space: “So clean. Everything is so neat and efficient. Spotless. The trucks come up, have all the space they need to back in, get out, and another comes in.”

That enthusiasm quickly fizzled. Wholesalers like to joke that the market outgrew its new home five years after it opened in Hunts Point. Trucks lie at the heart of that problem.

Trains cars sit quietly at the terminal.

When the market was designed in the 1950s, planners expected that a substantial portion of perishable produce would arrive by rail, then the dominant means of transporting food. Trucks were mainly used to transport produce within the city, delivering to individual stores and restaurants.

What changed was the interstate highway system, a federal initiative kicked off in 1956, which rapidly revised the logistics of shipping food. As long-haul trucking became faster and cheaper, trucks began to overrun the market. The trucks didn’t just multiply; they grew. When the market opened, refrigerated trailers — reefers — were 33 feet long, sometimes stretching to 45. By the 1990s, reefers extended 53 feet, the 18-wheelers now standard on our highways.

Fifty-three-foot tractor trailers are too hulking to maneuver in the spaces between decks; trailers generally have to be moved in without their engines. “There have been fistfights between drivers, literal fistfights over a parking spot because they need to get in and get their product and get out,” D’Arrigo told me. “It doesn’t happen that often, but when the market’s busy, the market’s busy.”

The highways that transformed the food distribution system also severed Hunts Point and its residents from the rest of the borough — especially the Bruckner Expressway, completed in 1973. For decades afterwards, the neighborhood languished.

Truck at the loading dock of the Hunts Point Market

·Image from Library of Congress

Although the neighborhood has become greener and safer in recent years, largely due to the tremendous efforts of the residents themselves, they still reap few benefits from being the market’s home. The South Bronx neighborhood has repeatedly been described as a “food desert,” with some of the highest obesity rates in the city.

The constant stream of diesel trucks serving the Food Distribution Center and other industrial facilities in the community also generate alarmingly high levels of particulate air pollution, contributing to concurrently high asthma rates. Kids in Hunts Point and neighboring Mott Haven are hospitalized for asthma at a rate more than double the city average. This situation has remained unchanged for decades.

“We have to work with the facility we have, to create the facility of the future.”

As Grant and Gomez show me around the market, they point out innumerable small changes and improvements. Bright LED lighting has improved visibility and safety. A recent partnership with the nonprofit Sharing Excess helps redirect food waste away from landfills. They point out refurbished electrical panels, and a repaired bit of rubber mat around a rail line. These may seem like small potatoes, but Gomez reminds me: Wholesalers operate with slender margins of two percent. Any savings are significant.

Both repeat hopeful slogans. “Fixing the market while it is still operating is like building a car while you’re driving it.” “We have to work with the facility we have, to create the facility of the future.” “We have to act like the market we want to be.” Their vision for a rebuilt, revitalized market includes not only wider, safer platforms, improved energy efficiency, and technological improvements (like digital infrastructure and electric truck charging stations), but a deeper and more sustaining relationship with the surrounding community. Rebuilding the market and revitalizing the neighborhood go hand in hand.

“Imagine the Potential”

It’s difficult to grasp just how large the market is, even when you’re in the middle of it on a busy night. This is because the market is always in flux, forming and reforming itself around the constant flow of precious, perishable produce. No matter how vast the load of lettuce, or the bounty of berries chilling within a million square feet of cold storage, we ultimately experience its goods on the most humble, intimate scale: as the components of the meal in front of us.

Looking down B Deck as the late-night hustle and bustle winds down.

It wasn’t until my second visit to the market at night, in early August with this article’s photographer, Lila Barth, that I began to grasp the market’s spread.

Grant and Gomez wanted to show off one of their recent green initiatives: the new “cool roof.” We followed them into a stairwell, up a ladder, and through a hatch, and emerged into the fresh clarity of dawn. The flat roofs of the market buildings had been coated with a dazzlingly bright white paint, specially developed to reflect heat and UV rays. By lowering temperatures in and around the buildings, Gomez explained, the paint would reduce the burden on air conditioning and other energy-intensive systems — potentially saving tons of atmospheric carbon. “When it’s finished,” Grant said with pride, “this will be the largest commercial cool roof installation in the city.”

The market stretched out below me, a luminous white fork. Manhattan’s towers reached up to the south. To the north, Hunts Point was slowly coming to life, the grid of its streets sloping up to the Bruckner Expressway. The Bronx River, silvery and calm, glimmered to the east. Once one of the most polluted waterways in the country, through decades of concerted efforts by community groups and environmental stewards, its salubrity has been largely restored. Kids now learn how to canoe and sail in a park right next to the market.

Looking north form the roof towards the Bronx's Soundview neighborhood.

The market, I realized, isn’t a place apart, a closed-off “gated community.” It is an integral part of this variegated, divided cityscape, key to its functioning and survival. And perhaps also to its renewal and flourishing.

Tangires, the market historian, describes public markets as essential civic institutions in 19th and 20th-century America. These were places where community values became municipal policies. Public markets are also points where the levers of the food system — that unthinkably vast and abstract thing — can be reached and shifted, and the system reshaped in response to emerging priorities and diverse needs.

“Imagine the potential,” Grant says. “We do wonders with what we have, but imagine the potential.”

This article first appeared in Ambrook Research Journal V. 01, a limited-edition print publication.