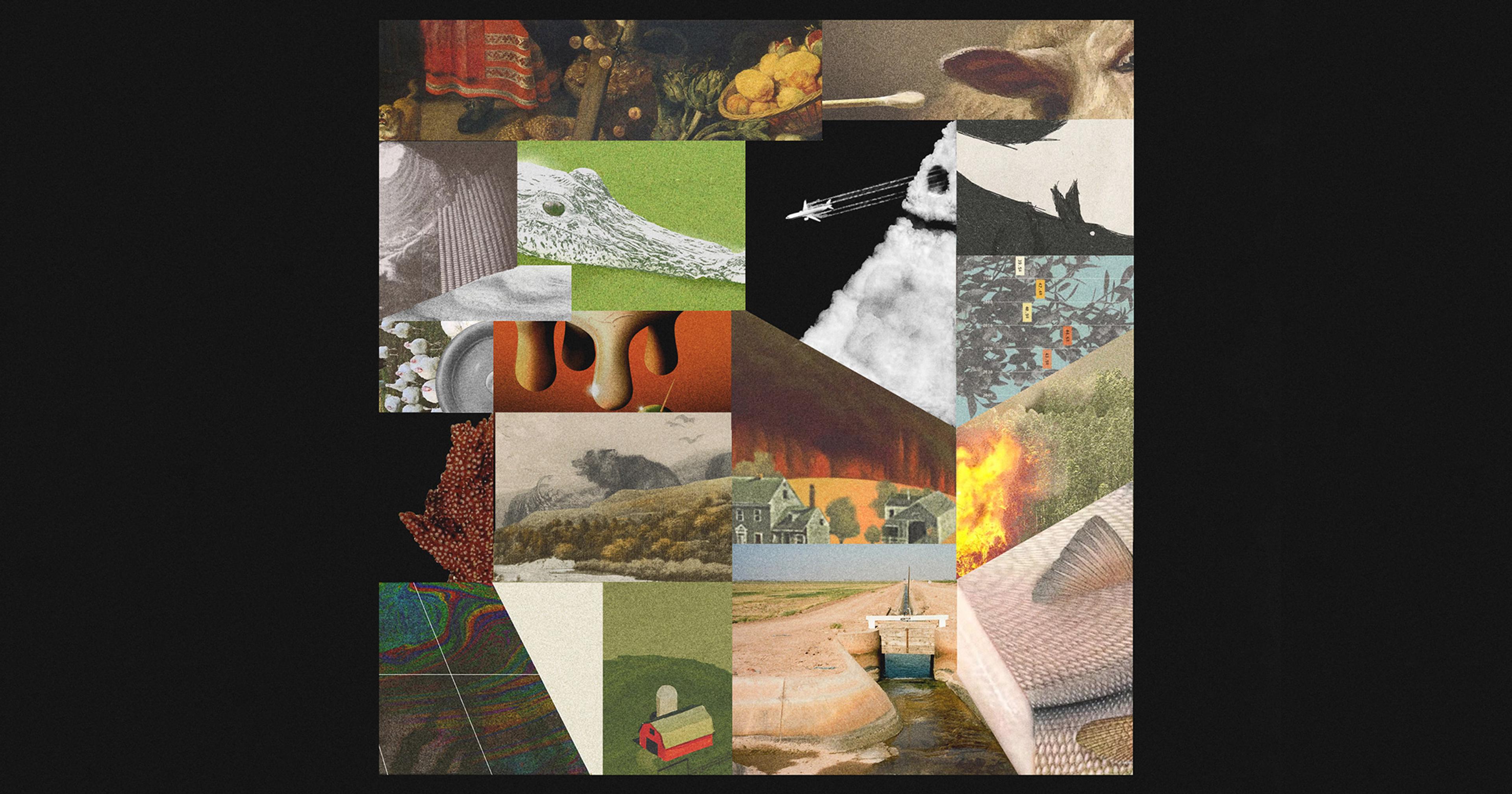

A Maryland farmer reflects on the tough balance of working the land while raising kids.

Every time I read the framed poem on my wall, tears cloud my vision. We bought our 85 acres of workaholics’ paradise when our children were 2 and 5. In the 14 years since, I have been the farmer and the homeschooling parent while my husband, whose dreams do not include farming, gallantly works off-farm for actual income.

For every happy memory I carry of the kids filling out grammar workbooks next to me while I hand-milked our cow, I have two of being torn between their needs for me and the farm’s. Of feeding hogs in freezing rain and trying to keep the kids warm while they whined. Of not taking them to sports or parties because I needed to mow the pasture, weed the spinach, wash the eggs...

We have a hundred photos of our son and daughter snuggling newborn lambs, pigs, and chicks, but none of me at 1:00 AM, exhausted from staying up for calving, cheese-making, or food-baking.

The splinter that lives in my heart is the question of whether I was fair to my children. The farm was my mental health but it was also my crazy. The work on the land brought me peace and meaning, but also terrible overwhelm. Looking back, I sometimes wonder if I took it on at their expense — and not to support us, because it didn’t — just for my own desire.

The night the sheriff’s deputy arrived at our door at 3 AM will long live in our family’s lore. Our cattle were out in the road. It turns out that herding scared cows in the dark and rain, on unknown ground, is a lot harder than regular pasture moves, but the kids (and husband) were champs about it. They summarized the experience as we finished with the sunrise: “I never want to do that again!” from my 15-year-old son and, “That was amazing! So fun!” from our 11-year-old daughter. These reactions correlated with their general attitudes about the farm.

Because of my daughter’s interest in farming, when she was very young we often did chores together while singing our theme song: “We are farmers, we are tough! We feed our animals in the nighttime, yes we do...” As she grew we rode ponies in the fields together and camped in the barn during lambing. However, I often wondered if my extroverted son would have been better off with a childhood in town. Not that he seemed to mind long stretches alone in the house absorbed in Legos and audiobooks, or later, novels to read and others to write, but he was sometimes lonely, and I often felt torn on his behalf.

Given this history, I was amazed when his interests turned to eco-activism and he began speaking publicly of his childhood on the land and how it had awakened his concern for the Earth.

The summer he turned 18, our hard-working, hard-saving son got on an airplane to spend six months traveling alone through Europe and Latin America. He returned in time to hike the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine, before starting college this past August. Somewhere along the way he found time to write the following reflection on his childhood; the poem that cracks my heart open a little more each time I read it on my wall.

Demeter and the ewes: two sonnets

by Davin Faris

I.

My mother—she keeps one hand in the earth

and one upon the sky, my youth a season

of unabashed witchcraft. Her reaching

inside a birthing sheep, the way a god

shoves life into a body, bloody and wild.

She pulled our hearts up from the garden, no wonder

the metaphors I adore are soil as miracle

and rainstorms as the braiding of the land.

The soul if it exists must first be taught

to love the flock, then not to weep at slaughter.

My mother—she invited death to dinner,

told me to shake his hand. Harvest, she said,

awaits us all, but don’t forget all we’re given.

Even now, a world away,

II.

I have not forgotten.

Leaving home I felt the face of winter,

the crop cut down, the blind lamb born too soon.

But my mother—when once I wept for springtime

she took my hand and led me to the ewes

their flat and golden eyes, their clouded forms.

Their tender dedications to the grass.

She said, you must learn this, the balance

of our home. The pasture’s precious weft,

bramble tracks beside the shadowed creek.

The eternity we reap and tend. Study it.

Know it as part of yourself, for then

you’ll reach the boundary of this earth

and as we are meant to, go.