For the first time, large farm groups are making affordable childcare a policy priority for the 2023 Farm Bill — a move that could help reshape and revive rural communities.

On 14 acres of rented land in central Ohio, first-generation livestock farmers Kerissa and Charlie Payne raise chicken, cattle, pigs, and lambs. The couple also has two young children, a newborn and an almost-two-year-old. That’s a lot of lives to care for.

It’s not always easy, especially considering how hard it can be to find affordable childcare. After giving birth to her first child, Kerissa jumped right back into her farm duties at Covey Rise Farm. “I had her on a Tuesday, and I was at the farmer’s market working on Saturday,” she said. Now, since having their second baby, the couple has had to cut several of the markets they participated in, missing out on thousands of dollars in sales. “You can’t take on another farmers’ market if you don’t have childcare for your kids. And most of the time, you can’t find reliable help.”

Nationally, 74% of farm families have experienced childcare challenges due to cost, availability, and distance to care. The lack of available options can hinder farm growth, forcing farmers to choose between growing their business and keeping their kids safe.

Could help soon be on the way? For the first time in history, the American Farm Bureau and the National Farmers Union have included affordable childcare in their priorities for the 2023 Farm Bill. A bipartisan bill that’s connected to the Farm Bill and sponsored by senators in several states, called the Expanding Childcare in Rural America (ECRA) Act of 2023, aims to direct funding towards opening and sustaining childcare centers in rural communities. “The men and women who work tirelessly to feed, fuel, and clothe us all deserve to raise their families in a healthy environment full of opportunities where children can grow and learn,” said Rep. Tracey Mann (R-Kansas) one of the seven members of Congress supporting the bill.

Of course, the challenge of finding affordable and quality childcare is not unique to the agriculture sector. Across the country, the childcare crisis is worsening — in rural areas, in suburbs, in cities. Waiting lists at daycare centers are getting longer, qualified staff are leaving for better paying jobs, costs are soaring, centers are closing.

“This is not a they or them problem, like farmworkers versus farmers, or even rural versus urban. This is a we problem for all Americans,” said rural sociologist Florence Becot, associate research scientist in Marshfield Clinic Research Institute’s National Farm Medicine Center.

That said, there are factors unique to farmers that further complicate their childcare woes. “One of the first things that we actually have to reconcile and start talking about is that yes, farm parents are working parents,” said Shosanah Inwood, associate professor of rural sociology at

Ohio State University. More often than not, both parents are performing farm duties, with some even taking additional off-farm jobs for reliable income and healthcare benefits.

“I had [my first baby] on a Tuesday, and I was at the farmer’s market working by Saturday.”

“The reality is, most farms in today’s world require both mom and dad to be working. It takes both parents to be on the farm. What worked 20 or 30 years ago isn’t what’s working now,” said Kerissa Payne, who oversees marketing, deliveries, and order fulfillment for the farm while also caring for her newborn full-time. The couple rents farmland that’s about a 10-minute drive from where they live, so farming duties can’t easily be completed during naptime. “I dream of the day when I can put my kids down for a nap and go outside and work and have the baby monitors watching them.”

Farming duties also don’t fit neatly in the hours of the traditional workday. “When you’re a farmer, your work hours are much longer. You can work weekends, evenings, very early in the morning. If you have livestock, if you have dairy, you’re milking two to three times a day. It’s nonstop,” said Becot.

Most childcare centers are set up to accommodate the 9-to-5 workweek schedule. “But we know that farming operates in the 24-hours-a-day, seven-days-a-week, non-traditional mode,” said Inwood.

Farms are not especially safe places for young children either. The number of large farms is increasing, as is the use of farming equipment that is much larger than they used to be, with greater potential to cause harm to small bodies during accidents. Every three days, a child dies in an agriculture-related injury, and at least 33 children are injured on the farm per day, according to the 2022 Childhood Agricultural Injuries Fact Sheet. “There’s really all these great things that are wonderful about growing up on a farm. But the reality is that farms are also very dangerous places to be,” said Inwood. She emphasized that for the last 20 years, farm safety experts have argued the best way to prevent agricultural injuries to children is for them to have a dedicated, off-the-farm caretaker.

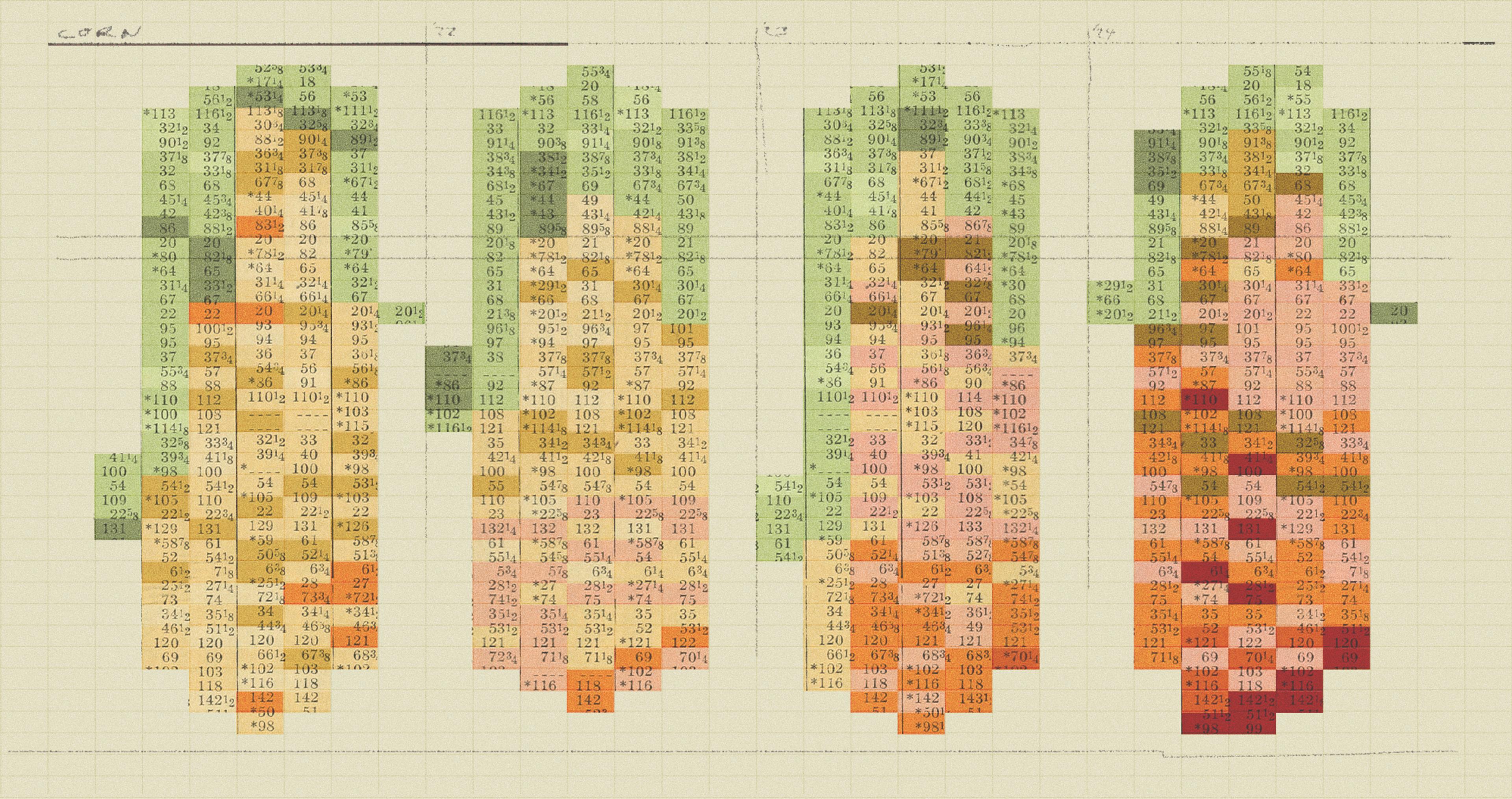

After working on Wall Street for seven years, corn and soybean farmer Adam Alson moved back to Jasper County, Indiana, to take over his family farm. He looked forward to raising his family in the rural community he grew up in. But when the only licensed childcare center in town closed in 2018, he and his wife, Carlee Tressel Alson, were faced with a dilemma. Carlee, a freelance writer, was working on an important project while pregnant with their second child.

“It takes both parents to be on the farm. What worked 20 or 30 years ago isn’t what’s working now.”

“We started trying to figure it out, asking ourselves ‘Is there a different way that we can do this? Is there a way for there to be affordable, quality childcare, that we can financially sustain?’” said Adam Alson.

Then they had a wild thought: What if they opened their own childcare center? In Jasper County, roughly 70% of children ages 5 and under live in a household where both parents work. “Those kids need somewhere to go,” said Alson.

Earlier this year, Appleseed Childhood Education, the nonprofit Alson co-founded, opened its first early learning center, called AppleTree, with funds raised through local philanthropy, USDA rural development grants, and a large dairy who invested in the center “because they see that having quality childcare in a place that’s 15 minutes away from where they are trying to attract talent is important,” said Alson. Of the 75 seats AppleTree has for pre-K aged children, he estimates around 30% are from families with some connection to agriculture.

Alson is hopeful that the model can be replicated in other rural communities across the country — especially if the USDA Rural Development receives authorization and funding in the Farm Bill to build and staff more facilities in rural communities, in addition to helping to subsidize the cost of childcare (on- and off-farm) for farming families.“We’ve cobbled care together before, but now we don’t have to,” said Alson.

Not all farm families are as lucky. This fall, the Paynes will move their operations to Kansas due to increasing land values in Ohio. They said the lower cost of childcare there will help them be able to continue to farm. The family’s dream of growing bigger, however, may have to wait indefinitely.

“I wanted a big family, but the reality is, I don’t know if we can afford any more kids unless we can find sustainable childcare,” said Kerissa. “The farming industry is gonna die if we don’t fix it. Unless we have childcare, it’s not going to work.”