A prodigal daughter moves from NYC back to Montana to help her family’s cattle give birth.

At the beginning of March, I began a 32-day shift that started each evening at 7 and ended the next morning at 5. I spent all my waking hours with cattle. Hi girls, I said over and over as I checked the heifers for signs of impending birth. I tracked the stars across a vast Montana sky, feeling my connection to place deepen while my sense of time was going absolutely batshit.

I was a night calver. Or, to put it in more evocative terms, a midnight bovine midwife.

To answer a frequent question: No, cows do not just calve at night. In fact, if you feed them late in the day, you can largely avoid these late-hour births. Many ranches no longer night calve, given changes in feeding, and the fact that this shift is terrible for anyone with kids or any kind of a life. Our ranch still largely feeds in the mid-morning. Beyond that, my family feels an obligation to our cattle that goes beyond the financial hit of potentially waking up to dead calves or injured mothers. Here, someone always stays up with them.

This year, that someone was me. I traded adjuncting in academia for working a calving lot. I’d been off tasting the world for two decades, now I needed to take care of my home. And so I left New York City in order to stare intently at cow butts. I couldn’t be gladder.

Birth and death tangle; anyone who’s spent time around the former could probably tell you that. During calving season, though, it’s multiplied on a scale that stretches time and thrums your ribcage. Calves slipped into the world in a crash of fluids, making the sound of a wave breaking. I moved quickly to clear the sacs off newborn noses, their first wet breaths on my fingers. Cows chewed afterbirth; the pale membranes swayed in the wind and snagged on tall grasses. Seemingly healthy calves died. Others galloped and tumbled across fields on impossible day-old legs.

It’s a bloody and beautiful world. My return is less surprising than the fact that it took me so long.

The Family Land

My Irish family immigrated to this valley in 1864. We’ve been ranching the thin, rocky soil ever since.

My sister and I grew up making the rounds with my father when he was the night calver. He’d tuck us in on an ancient mattress in the calving shack. The wind howled through the crumpled brick chinking, and through the door when he came in to warm up. Sometimes he’d put us in a wooden, heated box with a sick or rejected calf. It was warmer for us, and it was warmer for the calf. There we’d sleep, a tangle of young animals, Irish pale and black-furred.

Many of my kin, including my father and sister, felt the pull of distant places. In crowded cities, we played at being commissioners, lawyers, political operatives. I lived a life as a Seattle environmental journalist, then another one as a New York academic. The valley always calls us back.

As does a sense of familial commitment. My father’s still strong as a bull, but he’s 78. I can no longer pretend that we will have him forever. At his age, he’s earned the right to sleep through the night.

Most people know my dad for his twinkly-eyed friendliness — he’s got a knock-knock joke and a story for everyone. When we work, I see another side of him. He shouts directions and leaps out of the way of 1,300-pound cows. I’ve seen a bellowing heifer toss him over a fence. This season, I stood between him and a charging cow as he tagged her calf’s ear. I shook as I whipped the cattle prod to keep her back. I didn’t fear so much for myself as for the 78-year-old on the ground behind me. This is good work, but it can turn serious quickly.

I’m doing my best to learn, but the decades away put me forever behind where I should be.

Anatomy Lessons for a Late Bloomer

After high school, many of my neighbors studied agriculture and animal science. The other ranch kids had to find outside work, but it all seemed connected: jobs as invasive grass specialists, rodeo pickup men, welders, brand inspectors.

We’re all stepping up as our fathers slowly retire; my old classmates are incredibly capable, whereas I still feel like a kid. Teaching narrative structure didn’t exactly prepare me for how ranch life pans out.

This was especially stark in January when I attended a calving workshop in a nearby town. Many of the attendees were under the age of 12.

We ate dinner as the speaker, a veterinarian, calmly flipped through slides about absolutely everything that could go wrong. Over bites of lasagna, we heard about prolapse, and the care one must take so the cow doesn’t catch her dangling uterine on a fence. Diagrams showed the awkward positions a calf could get stuck inside its mother. The vet described “inside-out calves,” which is every bit as horrific as it sounds. I looked down and wondered if I could finish my plate, let alone handle being the night calver. I glanced around. The other kids seemed unphased.

The vet picked up a life-sized model of a calf. The fake calf’s head flopped back against her arm, and for a moment, the vet resembled the virgin Mary in an agricultural rendition of Michelangelo’s Pietà. She loaded the pre-greased Jesus into a stoic, fiberglass cow. The cow had a large hole in its side, so we could see into her body. The vet arranged the calf into the same stuck positions as the diagrams.

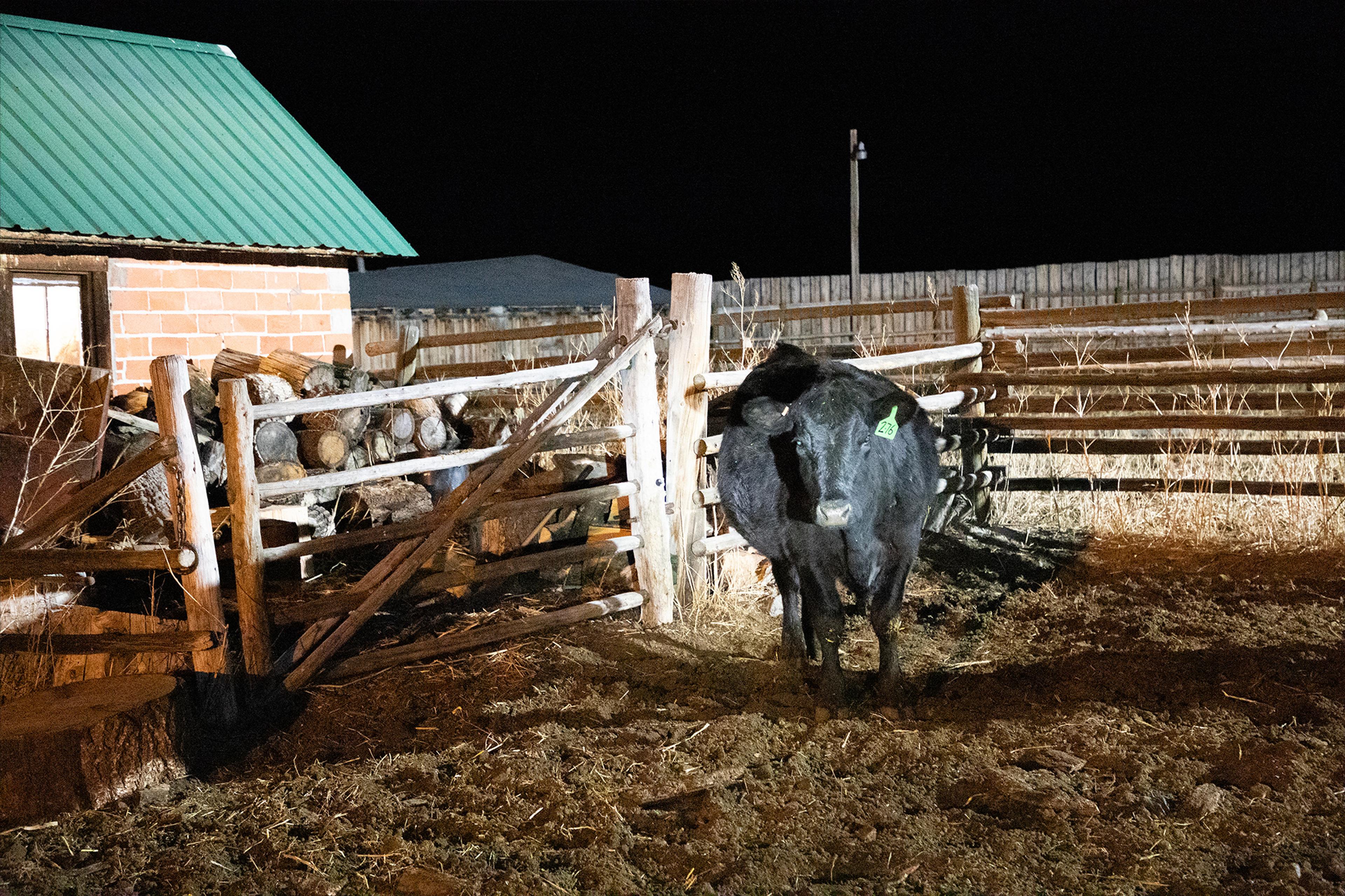

Above two photos by Darby Minow Smith

Then it was time to practice. Calves don’t get stuck frequently; most cows just need time to work through the stages of labor. Still, it’s a reality of calving season. Livestock vets spend spring traveling from distant ranch to distant ranch to work on difficult cases. Outside help is likely hours away. Knowing how to pull calves yourself is key to a well-run operation.

And so the children raced for a chance to pull out the calf as their proud parents looked on. They reached up the fake cow, and we watched their little hands seek to figure out what was going wrong. I didn’t participate in the pulling. I’d grown up with many of their parents, and I felt embarrassed by my lack of experience, unwilling to be shown up by 9-year-olds.

Thirty-two night shifts later and I’ve surpassed the competition, who needed to attend grade school after all. Fiberglass is far from a living, kicking cow, and the kids would need years of supervision and to be much stronger to pull real calves.

Amateur Hour(s)

As the night calver, I watched the heifers — young cows who have never given birth before — for signs of trouble. So many things can go wrong, as their bodies and minds are new to this, and their babies weigh 80 pounds.

Calves can choke on the sacs over their heads, overwhelmed mothers can turn aggressive, wet newborns can be abandoned shivering in the mud. A heifer can become permanently injured or even die, if her calf gets stuck inside and no one shows up to help.

I’ve long liked cows, but I grew to especially love my ward. The heifers rested across the corral, sides bulging like a field of overripe pumpkins. They flung their necks to groom their backs; their tongues barely connected despite grunting effort. They each had a different literal comfort zone, and I tried to avoid entering it so they wouldn’t struggle to their feet. Some stretched dramatically when they got up. One always made such a moaning racket, she sounded like a stiff old hound.

I checked for birthing signs. A subtly “springy” vulva could mean birth within the day. A calf should be on the ground in an hour or so if its hooves are dangling out of its mother.

A raised tail could be a helpful sign, as it gave time to move the heifer before her water broke. Except cows regularly raise their tails to piss, poop, fart. This meant frequently shining a flashlight on a cow butt, watching as her tail lowered inch by inch back into place, then shining the light on the next butt.

If the signs were there, I moved the heifers into a small pen. Then, I gave them space. I needed to observe without being intrusive. I peered over the top of feed tanks, kneeled behind fence posts, and peeked around corners. The heifers strained and stretched out their necks from effort. Sometimes their voices cracked, and they sounded just like they must have as calves.

I itched to help them, but I had to let them be. Despite all of the things that could go wrong, things mostly went right, and the heifers usually didn’t need me. A wet crash, and new life steamed on the ground behind them.

My favorite moments were when the cows first called out to their calves. They all know how to make a deep, sweet mmmmmmm. The heifers heard that noise when their mothers first turned to them, and now, they called it to their own babies.

Observing these births made me feel deeply lucky, but most nights, nothing happened at all.

On those long shifts, I set an alarm for every two hours, and tried to stay awake in my high school bedroom. I flipped through agriculture trade magazines and Anne Carson’s Nox. I watched farm accounting webinars and fell asleep drooling into 30-year-old carpet. The alarm shook me like I’d been out for days, not five minutes. I checked the cows with one eye glued shut from a dry contact. Back in my room, I tried to find the most expensive horse on RanchWorldAds. I laid on my back and looked up at a green ceiling I’d last painted as a teenager, until the alarm blasted me back into the night.

At 5 a.m., if nothing was calving, I left a note for my dad and crawled into bed for keeps. I would wake again when the day was already half over. Later, my parents would go to bed, and my eight hours of solitude would begin.

The Work Turns Serious

Four times this calving season, we needed to pull a calf. Each time, a heifer got stuck at some point in the birthing process. I called my father and answered his groggy but concerned questions. Each time, he got up and came to the corral, where he peered around corners at the struggling animal. In the calving shack, he asked about what happened when. When did I first notice her kinked tail? How long had it been since she tried pushing?

After he confirmed my concern, we moved to help the cow. We took her from the pen into a handmade chute. We trapped her head to hold her in place. And then we started something my dad had done hundreds of times, but was so new to me.

On one of the pulls, my father reached inside the heifer to see what was happening, and pulled out a foot. He looped a chain around it, and handed it to me to keep the foot from slipping back inside. He found the other foot and did the same. We attached small hooks to the chains for leverage. Pull when she pushes, he said. I watched the heifer’s sides puff out and then empty with effort. Pull! She swung to the side, and my dad crashed into me. The heifer roared. Wait for it, wait for it. Pull!

The heifer went down to her knees, and we fell with her. We kept the pressure as everyone struggled back up. Pull! My entire body strained to keep up with my father’s strength. Pull! The calf’s head made it through the pelvis. I could see its face on the other side of taut vulva skin, a fleshy vortex between here and the internal. Pull! The head popped out. Both eyes were open and staring, and its white umbilical cord was in its mouth. My dad kept up the pressure with one arm and cleared its mouth with his free hand. Easy now. The calf slipped so just its hind was inside. The 90-pound baby hovered between us and the cow, until it fell to the ground, and lay there steaming.

We checked the calf, and released the cow. She rushed out, overwhelmed by the pain and confusion. She turned the corner and skidded to a stop. She tentatively licked the top of her baby’s head, and then started working quickly. Mmmmmm, she said and licked. Mmmmm.

My father and I stood there grinning at each other and at the pair. Later, I’d overhear him bragging about my strength and my calmness with heifers.

For now, we needed to give the cow and her calf space. We walked out into the early morning. The day was just beginning for my father, and his night calver needed her sleep.