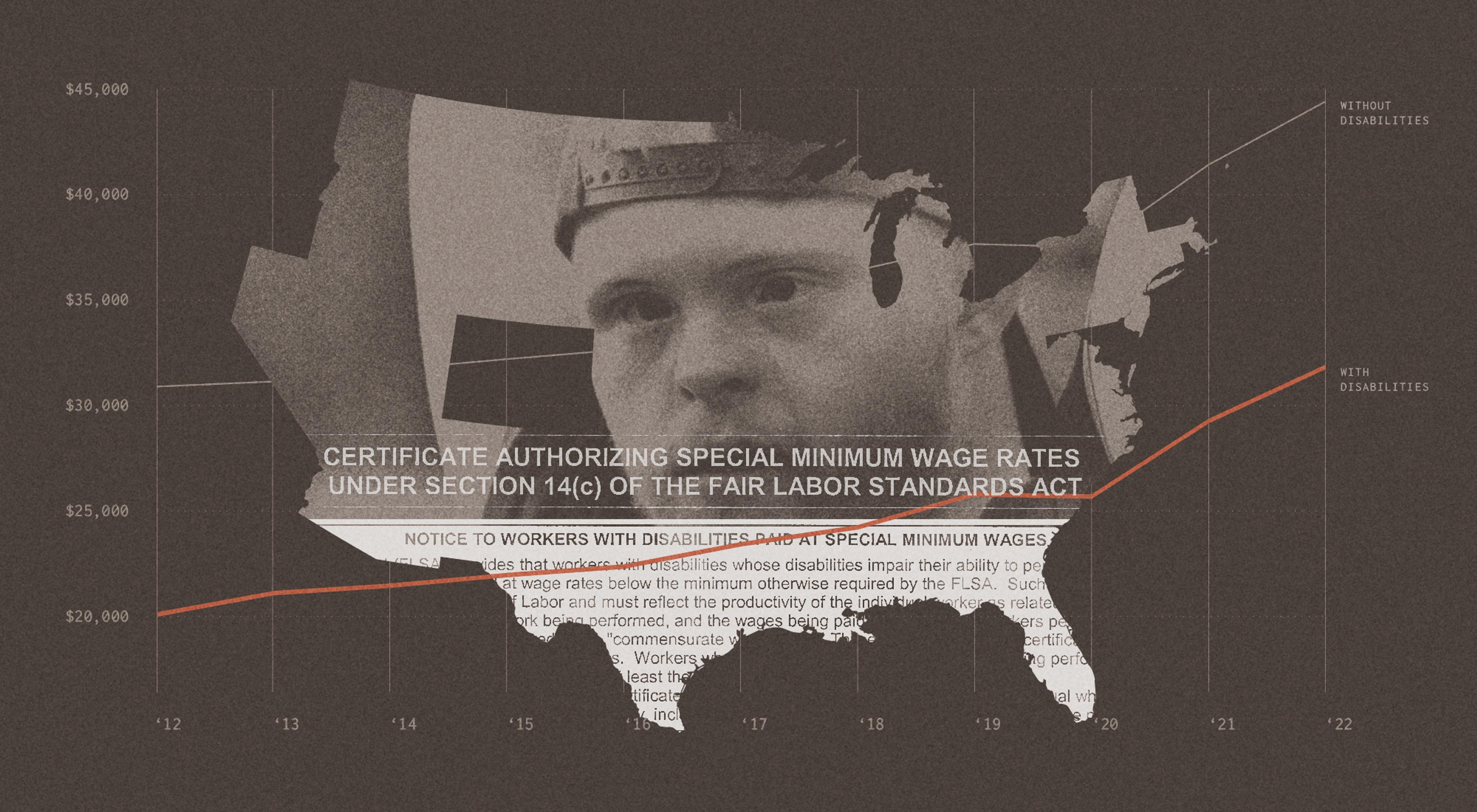

A special loophole has allowed employers to pay subminimum wage for decades. Legislators are finally pushing back.

Jack Butler is one of the directors at Achieva, a Pennsylvania-based organization focused on a range of services and job opportunities for people with disabilities, calls the usual employment options for intellectually and developmentally disabled workers what they are.

“We’re trying to provide more options than food, fetch, and filth.”

In America, it is legally possible to pay some disabled workers below minimum wage for their work, whether that’s working at a drive-thru, stocking shelves, or cleaning greenhouses — what Butler calls part of the three F’s. The provision that allows the subminimum wage is called a 14(c) certificate, named after the section of the Fair Labor Act that allows this level of payment. Now, some states are moving to abolish their use.

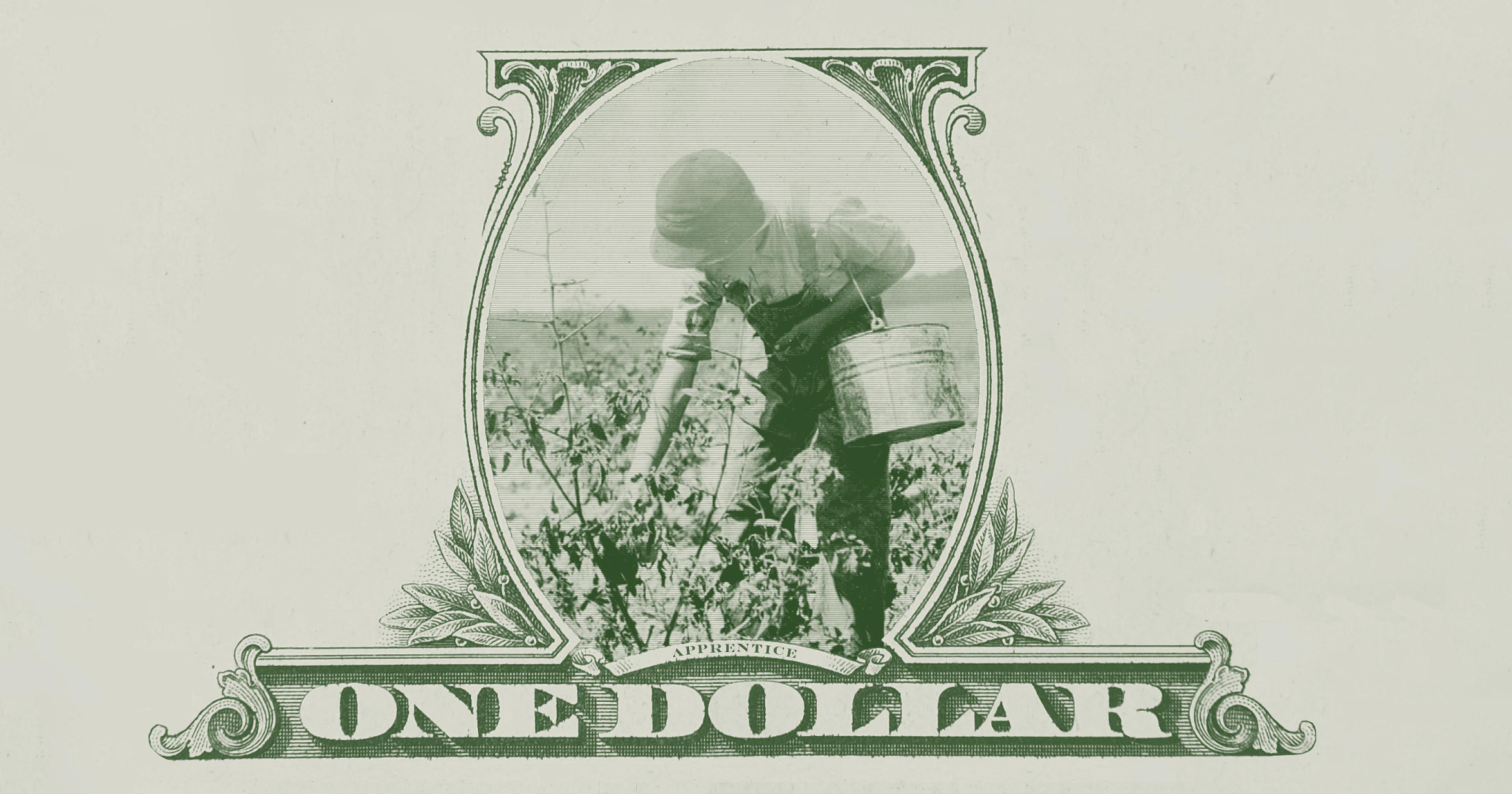

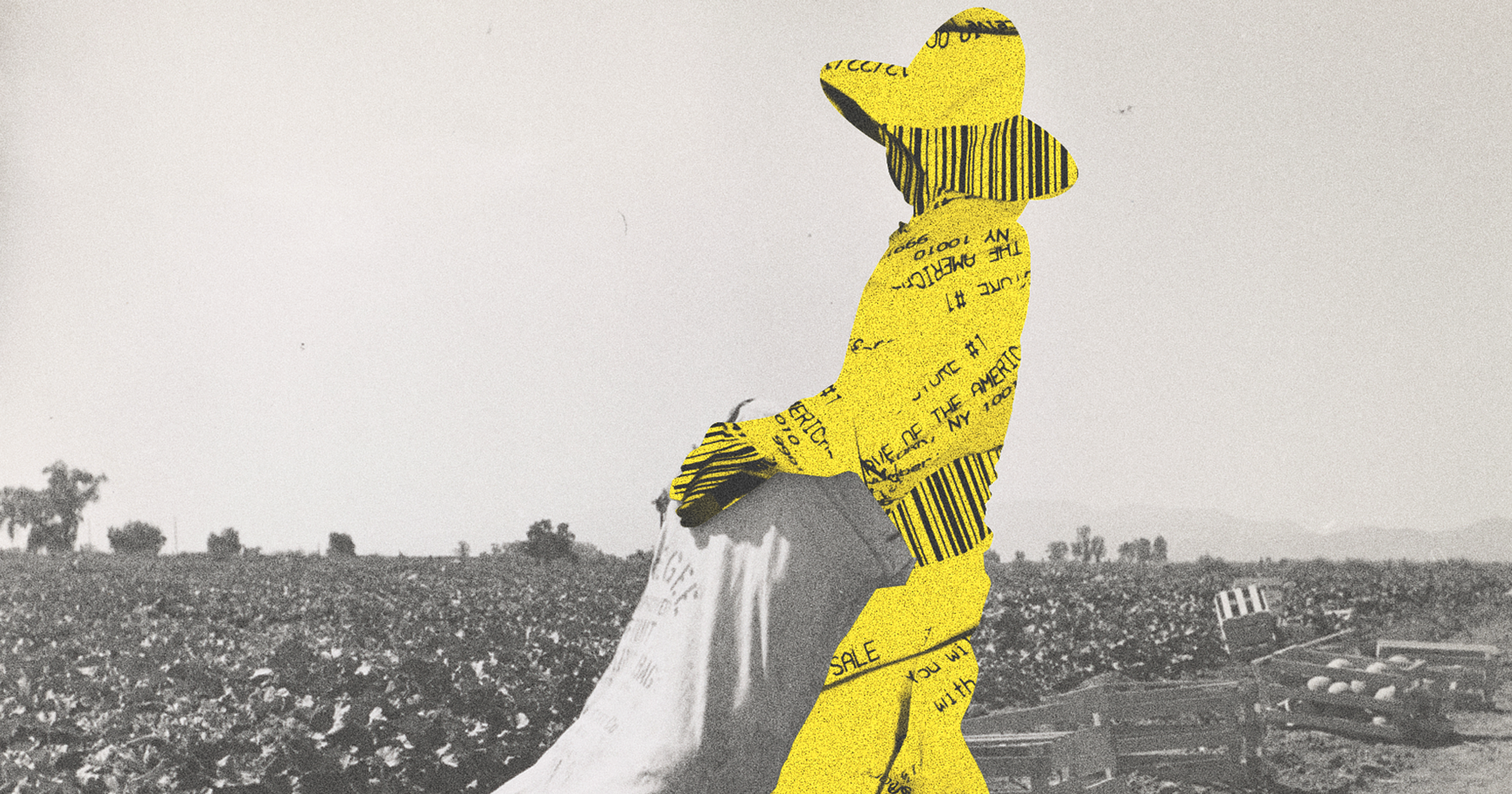

The agriculture and farming sector, like so many areas of the economy, is not immune from a practice that is unethical and exploitative. The 14(c) system operates much like the piecework system for foreign farmworkers, paying people by piece instead of by the hour. Though unlike the typical farm-based piecework system, it is entirely legal to pay less than the federal minimum wage.

If you want to see what wage your farm task would net you if you were under a subminimum wage, there’s even a set of calculators available online. For many employers, out of sight is out of mind and profit has proven to be king. 14(c) certificates are enticing for employers, whether they’ll admit it or not, because it means you can pay people for pennies and pretend you’re doing them a favor.

The 14(c) process was formalized into law as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, in an effort to get disabled people into the workforce. Colloquially known as sheltered workshops, the places where these programs operate have tended to warehouse disabled people, mostly those with intellectual and developmental disabilities, segregating them while selling the products they create. Many programs with 14(c) certificates lean on the idea that they can provide valuable vocational skills that can be translated to properly paying jobs eventually, though that transition rarely happens.

In recent years, at least 15 states have banned the practice of allowing 14(c) certificates to be used — Illinois committed to abandoning the program last month. Additionally, the Department of Labor (DOL) is currently seeking comment on a proposed rule change that would force a nationwide transition away from the program — though whether the incoming administration would implement any proposed changes is an open question.

Of the four organizations with obvious ties to agriculture who hold or have applied for 14(c) certificates — a list of current holders is publicly available — all appear to be billing agricultural production as a form of lifeskills development. None who were contacted responded to requests for comment. In total, as of publication, there are 751 14(c) certificates that have been approved, are in the process of renewal, or have been applied for for the first time. In total, that means just under 37,000 people are being paid less than minimum wage.

Using disabled labor on the farm is an approach as old as the hills. Stretching back to the late 1800’s, farm labor was used at institutions for disabled people under the guise of skill development and to offset the operational costs of the institutions. The Templeton Colony in Massachusetts, a state that still has four 14(c) certificates in use today, had a farming operation until the 1970s. This was a facility started by Walter E. Fernald, a key figure within the American eugenics movement, which sought to separate disabled people from the wider population by forcibly institutionalizing them. Those working in these “mini-institutions”, as the state of Minnesota calls them, were labeled inmates, not unlike the prison farm labor that is still used across the country.

Pennsylvania is one of the states that has committed to transitioning away from the use of 14(c) waivers, including a $14 million investment from the state’s government in October via federal funds. Lauren Avellone, an associate professor at the Rehabilitation Research and Training Center at Virginia Commonwealth University, is one of the people working to see more employment for disabled people nationally, working primarily with current 14(c) holders to support transition into a different model.

She noted some key reasons why we might see an underrepresentation of intellectually and developmentally disabled people in paying jobs within the agricultural sector: “A) Agriculture tends to be in more rural areas where transportation to work is a huge obstacle for people who cannot drive and do not have reliable public transportation, and b) people with complex support needs get wrongfully pigeonholed into a restricted number of professions in stereotypical jobs (e.g., janitorial, food prep, etc.) and so they are often aren’t represented in a diverse number of professions.“

One of the common arguments against the repeal of 14(c) is that the workers involved in these programs will have nowhere else to go, leading to less opportunities in the aggregate. Mihir Kakara, an assistant professor of neurology at NYU-Langone Health, is part of a research team that has found that this isn’t necessarily the case. Her research, published in JAMA Health, found that in two states that have eliminated 14(c), New Hampshire and Maryland, employment and workforce participation rates either increased or stayed level, depending on the funding provided.

“If not for these jobs and in sheltered workshops that pay subminimum wages, people with disabilities would go unemployed — [that] has always been the existing assumption,“ she said. ”We expect big level policies to have the same effect across states, but in the reality that is not the case ... And I think it makes sense that we should be looking at state level factors, also, in order to best optimize the repeal of Section 14(c) across other states which have been thinking about it.”

So, if the American economy still has a provision to pay disabled people less than everyone else, what does an equitable transition away from that look like? For Avellone, it starts with a multitude of efforts, including providing employee and provider training as well as benefits counseling; many disabled workers worry that an increase in wages could mean a decrease or elimination of the supports they need to live.

“The overall solution to ending 14(c) programs is not to close agencies and displace workers, but rather to train the same agencies in how to provide fully integrated employment services to the same clients they already serve who wish to work,“ she said. ”In my opinion, the biggest barrier has nothing to do with disability-related challenges but rather other people’s … perception of the ability of people with IDD to contribute to the workforce.”

Transport can one of the biggest barriers, especially in rural farming communities. Court Hower, Achieva’s president, said that finding employers willing to offer jobs to those who would have formally fallen underneath a 14(c) program requires a different approach to recruitment and logistics when it comes to those outside of urban centers.

“We’re working with one employee right now that’s in a very rural area, and it’s a large employer, but there’s no public transportation there and that poses additional barriers and challenges,” he said.

At the end of the day, the message from those looking to stop the use of 14(c), in agriculture and elsewhere is clear: Pay disabled people the wages they’ve earned. As Avellone put it, “...The 14(c) program is a dead-end road.”