A trial balance makes it easy to scan your books for potential mistakes. Here’s how to prepare one properly.

If you do your agricultural operation’s bookkeeping with spreadsheets or manual accounting software, the only way to be certain you aren’t making major mistakes is by creating a trial balance. It’s your frontline defense against errors—you can think of it as a ‘sanity check’ for your bookkeeping.

If you have an accountant, they may require you to bring them a trial balance each month so they can prepare financial statements for your ag operation. If you don’t, you need to run a trial balance before you use software or spreadsheets to prepare your own financial statements or tax return.

Here’s everything you need to know about trial balances for your operation—how they work, how to prepare one, and how to spot errors.

What is a trial balance?

In double-entry bookkeeping, every transaction has two parts: a credit and a debit. For the amount of every debit, there is an equivalent amount in credit; for every credit, there is an equivalent amount in debit.

A trial balance adds up all the credits and debits recorded in your double-entry bookkeeping system over a certain period to make sure the totals match. If they do, that’s a good sign. If they don’t, you know there’s an error somewhere in your bookkeeping.

A trial balance makes it easy to scan your ending account balances for potential mistakes. For example, if you have a large credit balance in a cash account, either your bank account is overdrawn or there’s an error somewhere. If a loan balance is lower than expected, you might have allocated 100% of your payment to the principal balance instead of recording some of the payment as interest expense.

Regularly running a trial balance ensures the entries used to generate your financial statements are accurate, so your financial statements will be accurate, too. (And you need those to be accurate to properly file your taxes, plan your ag operation’s finances, apply for loans, and do all sorts of other things.)

How often should you run a trial balance?

Many ag producers who do their own bookkeeping run trial balances haphazardly.

That is, they’ll wait until a period when they record a lot of entries in their general ledger—for instance, at the beginning or end of the growing season—and then run a trial balance to make sure the numbers add up.

But it’s best practice to run trial balances and generate financial statements on a regular, recurring basis—monthly or quarterly. That gives you better insight into how your operation is performing financially, and helps you catch errors sooner.

Also, if you apply for a loan from a bank, you will likely need to provide financial statements for your operation. You have a better chance of qualifying for a loan if your finances are organized, with regular trial balances and financial statements.

The trial balance vs. the balance sheet

A trial balance checks to make sure your books are accurate before you generate financial statements. A balance sheet is one of the financial statements you generate after running a trial balance.

The balance sheet lists all of your ag operation’s assets and liabilities. It’s an important tool for financial planning. For more, see How to Read a Balance Sheet.

The trial balance and double-entry bookkeeping

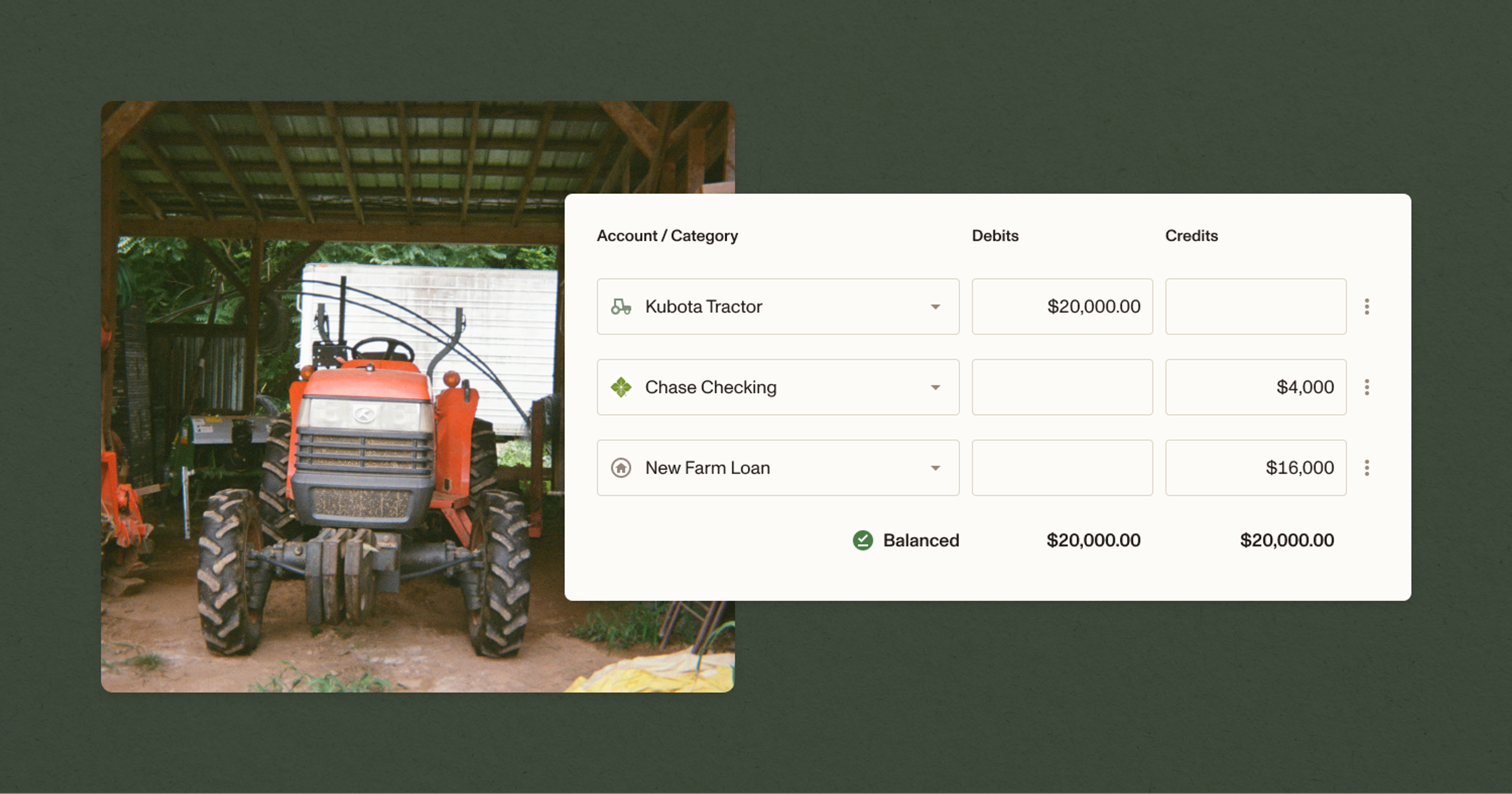

When you use double-entry bookkeeping, every transaction affects at least two accounts. All transactions are categorized according to account. The accounts you use for categorizing transactions are listed in your chart of accounts.

For instance, if you sell produce to a buyer, you might debit your Cash account and credit your Sales Revenue account.

Or, if you purchase supplies, you would debit your Supplies Expense account and credit your Cash account.

It can get more complex than that. For instance, if you buy a $30,000 tractor, making a $10,000 down payment and paying the rest with a loan, you might debit Equipment $30,000, credit Cash $10,000, and credit Notes Payable $20,000.

For more detailed versions of these examples, and deeper dive into double-entry bookkeeping, check out our Intro to Journal Entries.

The bottom line is that, by preparing a trial balance, you’re making sure that all the debits and credits balance out—so you can rest assured your books are accurate.

Double-entry account categories

Each account you use in your double-entry bookkeeping system falls under a particular category. And each of these categories has a “normal balance” that’s either as debit or as credit.

| Account category | Examples | Normal Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Asset | Cash, Inventory, Equipment | Debit |

| Liability | Accounts Payable, Notes Payable | Credit |

| Equity | Owner’s Capital | Credit |

| Revenue | Crop Sales, Livestock Sales | Credit |

| Expense | Feed Cost, Supplies Cost | Debit |

Your own chart of accounts may look a bit different. The important thing to remember is that, when you prepare a trial balance, all of the credits and debits should balance out.

How to prepare a trial balance

If you have many journal entries to go through, preparing a trial balance by hand can be a lengthy process. That being said, the steps you follow are fairly straightforward:

List all accounts. Each row in your list of accounts includes two columns: one for debits, another for credits. Record the ending balance for each account as either a debit or a credit.

Add up all the amounts in the debit column. Record the total at the bottom of the column.

Add up all the amounts in the credit column. Record the total at the bottom of the column.

Compare the total for each column. If your trial balance is free of errors, the two amounts will be identical.

Check for errors. If the two totals for debits and credits differ, you need to identify the source of the error. More on that below.

Adjusted vs. unadjusted trial balances

If you use the accrual method of accounting, you may need to prepare two trial balances: an unadjusted trial balance, and an adjusted trial balance.

Quick refresher: The cash basis method of accounting records transactions based on when money changes hands. The accrual method records transactions based on when you earn revenue or incur expenses, regardless of when cash changes hands. (For more, see Understanding Accounting Methods: Cash vs Accrual Basis.)

For example, suppose you sell grain to a buyer in October, but they don’t pay you until November. With the cash method, you record the sale in November, when you collect payment. With the accrual method, you record the transaction in October, when you make the sale, even though you haven’t received payment.

If you use the accrual method, you need to make adjustments to your trial balance to correct this difference between what is reflected in the books and what is reflected in the actual movement of cash.

You do this by first preparing an unadjusted trial balance, listing your total debits and credits exactly as they appear in your general ledger. Then you generate an adjusted trial balance, which takes into account how money has entered or left your business.

An adjusted trial balance is essential for producing a statement of cash flows, a key financial statement in accrual accounting.

Trial balance example

Talking about trial balances in the abstract, it can be hard to get a picture of what a completed trial balance looks like.

Here is an example trial balance for the month of August, for an ag operation using cash basis accounting. It records only the financial activity that occurred during the month.

Trial balance for the month ending August 31st, 2025:

| Account Name | Debit ($) | Credit ($) |

|---|---|---|

| Cash | 18,500 | |

| Crop Sales Revenue | 12,000 | |

| Livestock Sales Revenue | 5,000 | |

| Government Subsidy Income | 2,000 | |

| Owner’s Equity | 12,500 | |

| Feed Purchases | 3,500 | |

| Seed & Fertilizer Purchases | 2,200 | |

| Fuel and Oil Expense | 1,300 | |

| Equipment Repairs | 1,000 | |

| Utilities Expense | 800 | |

| Wages Paid | 3,200 | |

| Insurance Premium Paid | 1,000 | |

| Totals | 31,500 | 31,500 |

Note that the Cash account lists the total cash assets held by the business after taking into account revenue and expenses.

Here are the financial activities reflected in the trial balance:

Sales of harvested crops totalling $12,000

Sales of livestock totalling $5,000

Government subsidy payments totalling $2,000

Feed purchases totalling $3,500

Seed and fertilizer purchases totalling $2,200

Vehicle costs (Fuel and Oil Expenses) totalling $1,300

Equipment repairs costing a total of $1,000

Utilities payments totalling $800

Wages paid totalling $3,200

Insurance premiums totalling $1,000

A total cash balance, at the end of the month, of $18,500

Common trial balance errors (and how to fix them)

If the total debits and credits in your trial balance don’t match, there is an error. That error could either be one you made while preparing the trial balance, or it could be an error in your general ledger.

Here are some common mistakes to look out for:

Mathematical errors

The first place to look for errors is the trial balance itself.

If you incorrectly added up your total debits or total credits, it could be the reason the totals don’t match. Do the math again to make sure you didn’t leave anything out.

If that doesn’t work, look at each account individually and review the entries in your general ledger. You may have left out an entry for a particular account, or else accidentally entered it twice.

Single-sided entries

If you enter a transaction with only debits or only credits in the general ledger, it will result in a single-sided entry. That means you recorded a debit without recording the matching credit(s), or vice versa.

The only way to correct this error is by carefully reviewing your general ledger and making sure that each entry has one or more matching entries that balance it out.

Unequal debit or credit entries

You can make an error in your general ledger by entering a transaction and then entering its balancing transaction incorrectly.

For instance, if you debited Supplies $5,000, but only credited Cash $500, the entries would be unequal. They would also be unequal if you debited Supplies $5,679 and credited cash $5,697.

Here’s a shortcut for finding errors: on your incorrect balance sheet, determine the difference between your total debits and total credits. If the difference is divisible by 9, it could mean that the digits were switched in an entry (e.g. 97 instead of 79).

Wrong side postings

You will run into problems with your trial balance if one of your ledger entries that was meant to be a credit was actually recorded as a debit, or vice versa.

For instance, if you record a cash receipt as a credit to Cash rather than as a debit, the error will be reflected in your trial balance.

Calculate the difference between total debits and total credits on your unbalanced trial sheet. If the difference is divisible by 2, it may mean a wrong side posting is the reason for the mismatch between the two totals.

Ambrook helps you find the right balance

If you’re losing sleep over bookkeeping errors, it could be a sign your work-life balance is out of whack. Ambrook automatically imports your transactions, categorizes them, and makes them easy to reconcile, guaranteeing the financial side of your ag operation runs smoothly.

Plus, with time-saving bookkeeping automation features, automatically-generated financial reports, streamlined bill pay and invoicing, and other powerful accounting and financial management tools, Ambrook doesn’t just balance the books: it takes the guesswork out of running your business. Want to learn more? Schedule a demo today.

Want to learn more about Ambrook?

This resource is provided for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute professional tax, legal, or accounting advice. The information may not apply to your specific situation. Please consult with a qualified tax professional regarding your individual circumstances before making any tax-related decisions.