With 6 million active members, America’s largest farming organization is guided by the concerns of the many.

Editor’s Note: This essay is part of our Debates series, where two writers express differing views on the same issue. The other perspective on Farm Bureau can be found here. Opinions expressed do not represent those of Ambrook or Ambrook Research.

In the last quarter of every year, when farms around the country slow their production and equipment waits at a lull, “meeting season” begins. Meeting season is a slower time between harvesting and planting when farmers can review their finances heading into a new year; apply for grants, loans, or agricultural assessments; or make their hiring plans. It’s also a time to gather thoughts on, say, the changing agricultural landscape and the challenges they face from political and regulatory bodies.

For the six million farmers that are part of American Farm Bureau Federation, meeting season means developing policy to advocate for the small family farms that account for 86 percent of farming operations in America. As the CEO of New York Farm Bureau, I have been fortunate to witness this type of “democracy in action” first hand.

The group’s origins are found in Upstate New York, when a group of farmers partnered with local chambers of commerce and railroad companies to ship farm products like grains, hay, and apples to other parts of the country. The first “Farm Bureau,” as we know it today, gathered in 1911 in Broome County, New York, to establish agreements and policies and ultimately push for legislation to help small family farms. By 1919, 38 other states had created their own Farm Bureaus, and they all came together to form the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Today, all 50 states, plus Puerto Rico, are part of American Farm Bureau; it is the largest voluntary general farming organization in the world. Farm Bureau membership is as diverse as agriculture itself, and internal contention has made the organization slow to adopt progressive policy. Over the last 10 years, that approach has waned, however, and diverse opinions have led to positions that address a range of environmental, climate, and social justice issues.

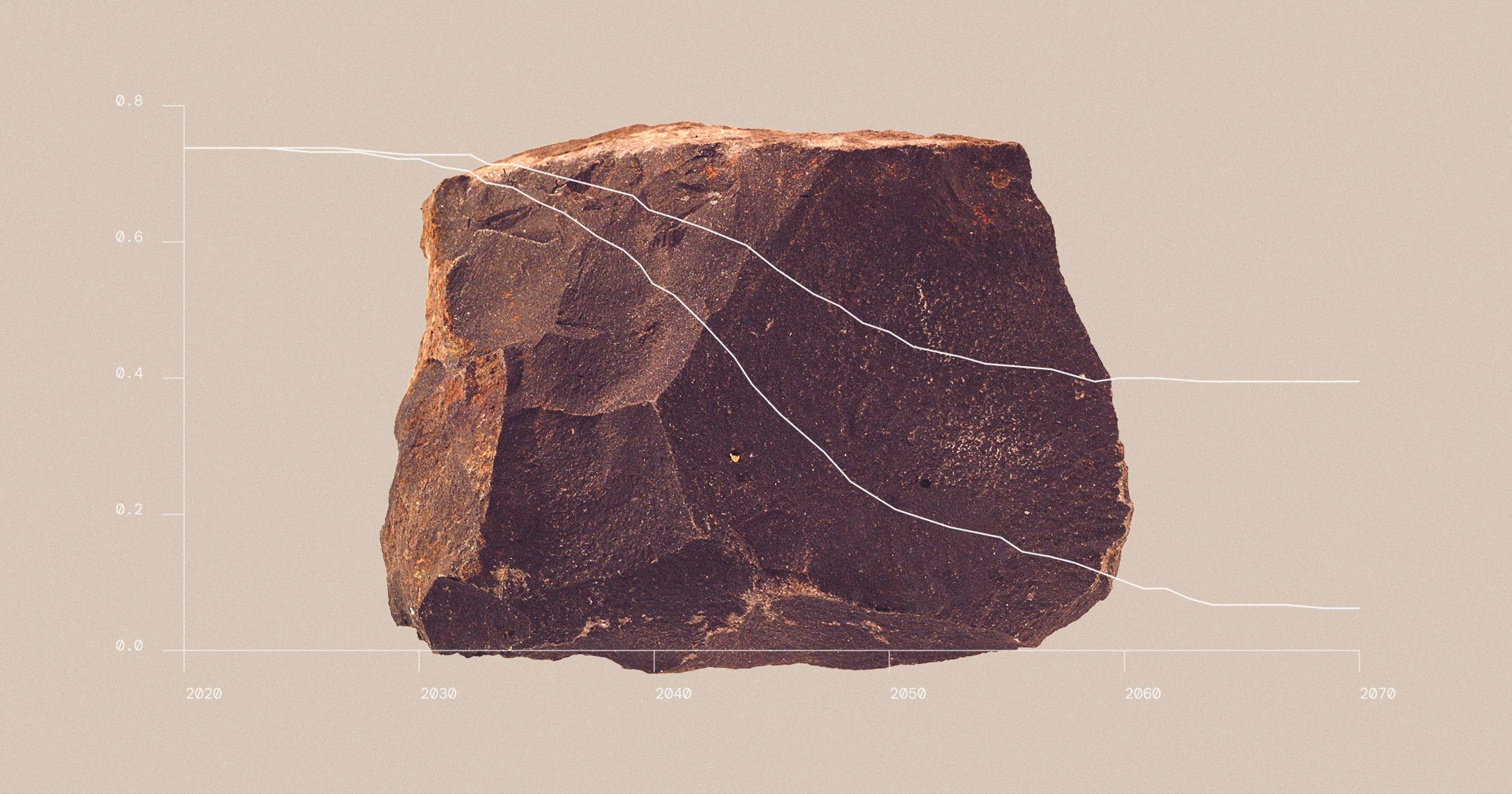

Farm Bureau has not always advocated for climate-friendly policy, but in 2020 it was a cofounder of the Food and Agriculture Climate Alliance, which advocates for incentive-based and market-oriented programs to combat climate change. Other recent national priorities include the promotion of forestry practices to enhance carbon sequestration; federal funding to increase public awareness of smart climate practices in agriculture; and programs for U.S.-grown biofuels.

One thing that has not changed is the grassroots policy development that defines the Bureau’s commitment to family farms. The process is fascinating. Political affairs staff are on hand to assist, but it is truly driven by the farmers, from all corners of agriculture, who join around a table to debate and discuss. In the fall of 2024, I attended 18 of the 52 county Farm Bureau policy meetings across New York State, along with several statewide policy meetings, and heard the concerns of farmers across an agriculturally — and geographically — diverse state.

The policies are at times hyper-local, as in the case of a recent Long Island farmer who advocated for an amendment to state law that would allow him to sell beer that was produced within 20 miles of his roadside oyster stand. Other policies reflect issues that widely impact farmers, such as requesting that state and federal authorities use calculations that include humidity and heat index data when creating working standards for fields and barns.

Some policies are hyper-specific, like the request that certification of equine dentistry be overseen by the state department of agriculture and not the department of education. Other policies span multiple commodities, as in the case of advocating for defenses against bird flu in the poultry and dairy industries.

These proposals come from the firsthand, lived experience of these farmers.

In all of the policies that are proposed and drafted, one thing remains constant: The respect of differing viewpoints is honored, and a commitment to providing sustenance for all Americans is the unifying thread.

These proposals come from the firsthand, lived experience of these farmers. Policies regarding nutrient management and water protections come from those who farm near wetlands or waterways. Policies on the use of plastics in packaging come from the hobby sheep farmer who achieved her retirement dream of spinning yarn and selling it to a local craft store. Policies that support healthy nutrition programs come from the urban farmer who turned vacant lots into a series of community gardens.

Policies on agricultural labor protections and support come from the farmer who milks 3,500 cows, as part of a national dairy cooperative, with year-round migrant employees. And it comes from the orchardist who welcomes migrants on H-2A visas for a few months a year who want to earn as much money as possible by the end of season. And it comes from the small organic farm and CSA operation, run by a young married couple, that wants to ensure that it will not be issued hefty labor violations if their children help hand over shares to customers each week.

When conflicts do arise, they are generally met with equanimity. Painful reckonings of the history and future of agriculture are considered in these workshops, but regardless if the policy came from someone with millions of dollars in egg production contracts or a CSA farmer grossing five figures a year, the recognition that there is room for all voices is the most inspiring part of Farm Bureau policy development for me.

This process creates parity and equity, with comprehensive legislation that protects all farms despite size or commodity. Every farmer can rally other local farms to join Farm Bureau and cast a vote for proposed policies. Farming, at its core, is a business, and these measures are designed to ensure that any member, regardless of size, can fight for their share of the pie.

While large corporate ag entities may have the financial power to influence Capitol Hill, Farm Bureau continues to ensure that the stories of those who actually feed us will have the greatest impact.

Becoming a Farm Bureau member is generally the same from state to state. In some way, the individual applying for membership must support the vitality of agriculture. The membership composition tends to reflect U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) statistics on farm size in this country. Large agriculture operations, whether owned by a family or a corporation, must follow the same membership process as smaller family farms who hold membership in Farm Bureau. The rules remain the same, no matter the size of your operation: one member, one vote.

As a democratic, majority-rule organization, the final items that are included in the policy book are voted on by each state at annual meetings. In January of the following year, the process is replicated on the national level at the American Farm Bureau Federation’s annual conference. Each state submits policy proposals for consideration by the attending membership, debate is had, a vote is taken, and a federal policy book is created to guide national advocacy. Items pertaining to federal funding; environmental regulation, and climate protections; trade and tariffs; and interstate commerce for agricultural products are the general focus of national policy.

These policies then drive the national lobbying efforts of Farm Bureau. The organization’s national budget comes mostly from the five dollars paid from each member of a state Farm Bureau. In 2024, American Farm Bureau Federation spent $1.3 million on national lobbying efforts, according to federal reports.

Throughout the year, Farm Bureau staff will draft bill language and submit public comments on behalf of the farmers to directly influence state and federal law and regulation, but the greatest impact comes from the farmers who embark on hill climbs and meetings with legislators. Here, those family farmers have their voices directly heard and advocate for keeping agriculture in the hands of the families who have cared for and tended to land and livestock for generations. While large corporate ag entities may have the financial power to influence Capitol Hill, Farm Bureau continues to ensure that the stories of those who actually feed us will have the greatest impact.

For this, I am thankful.