Elsewhere in the world, juvenile pigeon is a delicacy. But in the U.S., there are only a handful of squab producers — for now.

In 2015, Pennsylvania hobby farmer Daniel Leiber showed up to a French fine dining restaurant in New York City with some cuts of lamb and pork, hoping to turn his livestock pastime into a business. If this meeting went well, it would be his first restaurant account. If it didn’t, he was going to need to find another way to make an income off of his growing farm. In the end, things took a turn he wasn’t expecting.

This is good, the executive chef told him. But do you think you could grow me some squab?

“I didn’t even know what squab was,” Leiber said. “He could see that on my face.”

The chef explained that squab are juvenile pigeons — and no, they weren’t the same as the ones perching on statues and buildings around the restaurant. Pigeons grown for food are commonly consumed in other parts of the world, such as China and France. It’s common, for example, to see deep-fried squab on Chinese New Year banquet menus, or roasted and served at Michelin-starred French restaurants. These pigeons, which are raised as livestock, harvested as juveniles, and called “squab,” are thought of as a delicacy. And, since this restaurant happened to serve high-end French food, the chef wanted them on the menu.

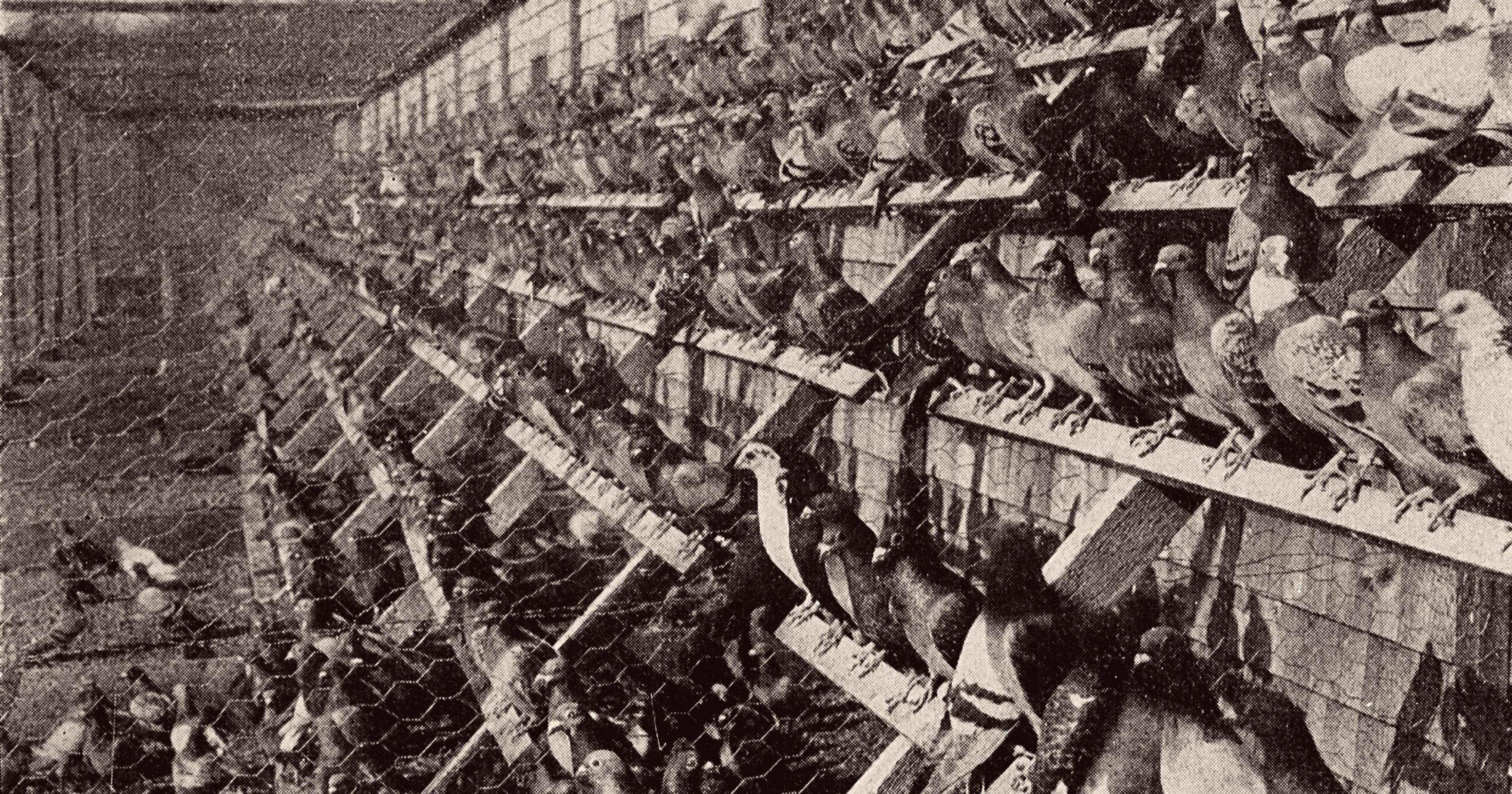

Fortunately, Leiber was up for the challenge, and quickly found out why the chef had made such a query of someone with no experience — squab farmers are few and far between in the U.S. He had to mostly teach himself the craft of “squabbing,” because the only help he could find nearby was someone who raised pigeons for show. He purchased a few King pigeons, built them a dovecote (pigeon house), and started working on creating his own custom feed. Within a few months of that first meeting, the New York City restaurant had Stardust Farm’s squab on the menu.

In January of this year, there were 869.3 million broiler-type chickens hatched in the U.S. Squab numbers are much harder to get ahold of, but the most reliable estimates are that we produce barely more than a million squab annually. In the U.S., squab is what Leiber calls “a lost delicacy.” But it wasn’t always so hard to find.

Not What You Think

Most people are familiar with city pigeons, but these urban-dwelling birds only represent a small facet of the wide variety out there.

“If you go on our website, you can see all kinds of different colors and varieties that don’t look anything like the [pigeons] you see out in the wild,” said Tim Heidrich, secretary of the National Pigeon Association.

Heidrich said there are hundreds of pigeon breeds, and they can generally be sorted into four categories. “Fancy” pigeons are raised for showing. Racing pigeons are raised for speed. Performance pigeons are trained to do tricks. And “utility” pigeons are used for squabbing.

Heidrich himself has been keeping fancy pigeons since he was a child in the 1960s and ‘70s, when he says it was much more common. Anecdotally, several other kids in the neighborhood kept backyard pigeons, inspiring him to get into the hobby. He started with two birds, whom he named Hank and Henrietta. Today, he maintains a dovecote with a couple hundred birds, including four breeds that he shows at competitions. But beyond show value, he also just really likes them.

“Chickens don’t interact with you as much as pigeons do,” Heidrich said. “The pigeons, they just seem to have much more personality to them.”

Culturally, pigeons have played many roles for humans. Like Heidrich, many people have kept them as backyard pets. They have been messengers, entertainers, and even took part in World War I, providing critical communications services by carrying messages. There’s a laboratory in Utah that studies pigeons for their impressive genetic variation. But raising pigeons as meat is one of the key ways humans have interacted with pigeons through time.

“Chickens don’t interact with you as much as pigeons do. The pigeons, they just seem to have much more personality to them.”

Squabbing as a practice has been around for thousands of years in many parts of the world such as Europe and North Africa. In England and France, there were thousands of dovecotes belonging to members of nobility in the 16th and 17th centuries. But the practice has faded over time, and while there’s a minor pigeon market in the U.S., it’s not that common.

“It never caught on in the U.S. that I know of, in any big way,” Heidrich said.

Bigger companies like Palmetto Pigeon Plant in South Carolina dominate a rather meager industry in the United States. Hanna Raskin of The Food Section reports that in the U.S. there are only 13 producers authorized to sell squab across state lines.

Most folks looking to buy squab in the U.S. must turn to online ordering or specialty meat markets. Paulina Market in Chicago is just such a place. They sell squab online and in their brick and mortar to retail customers. A spokesperson for the shop said they don’t sell much of it, though — it would be a big month to even sell 12 birds, they said. However, they added, sometimes that number doubles around the winter holidays.

The low numbers may be partially due to the fact that pigeons have gained a reputation as dirty birds — a misconception that both Leiber and Heidrich enthusiastically deny. For some Americans, the rugged urban ones have tainted their perceptions of this protein. But it may also be because the industrialization of animal agriculture requires the most meat for the least input, a demand that’s particularly difficult for pigeons to meet. As the quick-producing chicken took center stage as America’s most popular animal protein, squab has all but faded from view.

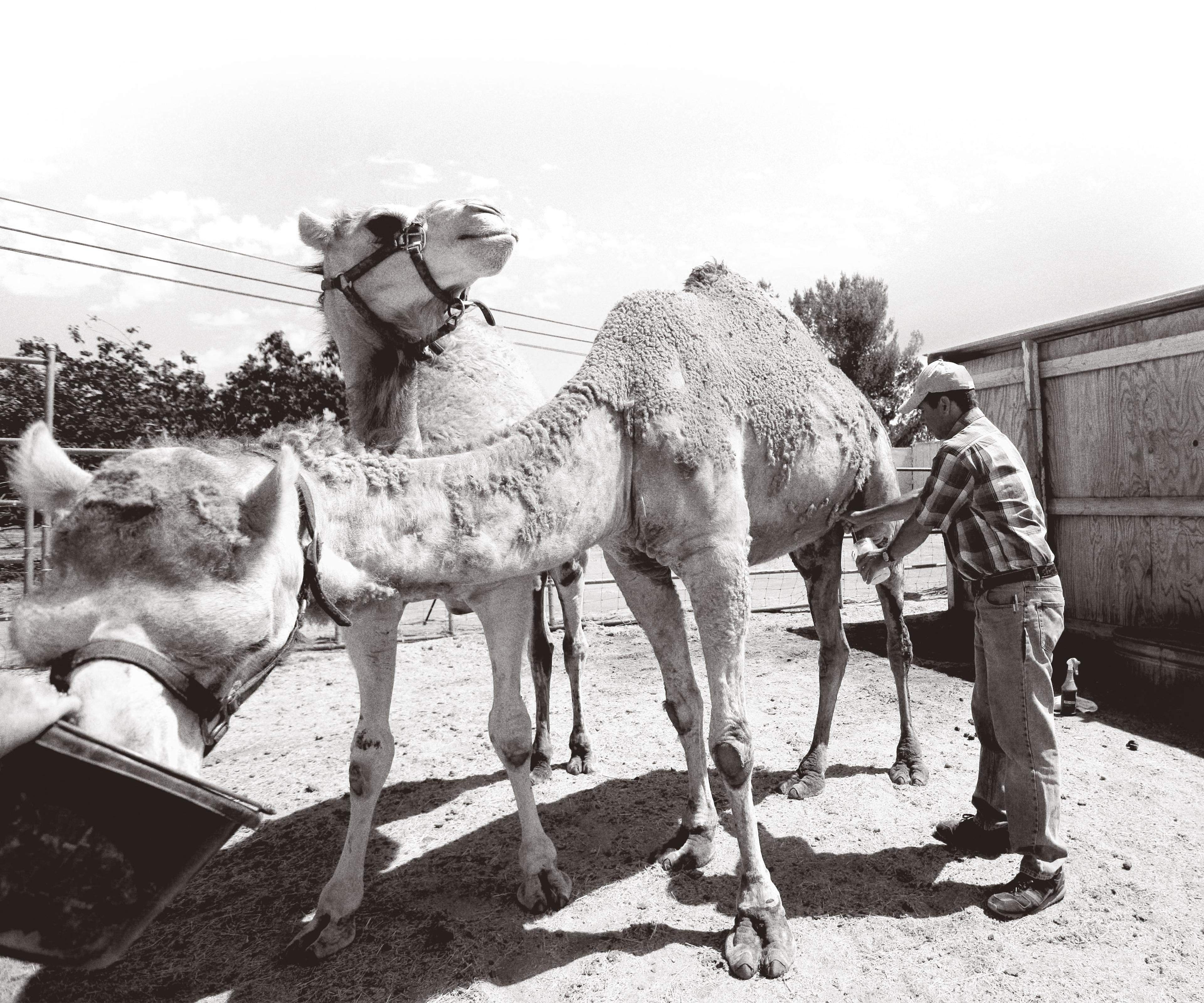

Raising Pigeons

It’s not that squab farms are impossible to scale up — Palmetto Pigeon Plant has tens of thousands of birds. But raising pigeons is a little different from poultry like chickens, explained Leiber.

“You could take a fertilized chicken egg, put it in an incubator, hatch that egg, and within three days, the baby chick is already eating grain on its own,” Leiber said. “With pigeons, you need the parents.”

A mother pigeon will lay only two eggs at a time, and the parents will take turns incubating those eggs. It takes just shy of 20 days to hatch these eggs, and then both parents will assume the responsibility of feeding their young.

The bird is meant to be tender, owing to the fact that they are butchered so young. Leiber harvests his at a month old, before they’ve left the nest.

“In a perfect world scenario, I’m pulling the squab right out of the nests so they’re not even flapping their wings yet. You can imagine how tender the meat is.”

“I’m pulling the squab right out of the nests so they’re not even flapping their wings yet. So you can imagine how tender the meat is.”

Covid-19 nearly ended Leiber’s career as a squab farmer. Before the pandemic hit, Leiber’s flock was about 1000 birds, or 500 pairs. When restaurants started closing down, he had to significantly cut down his flock. Leiber, who has a pigeon tattooed on his arm, took the culling hard.

“It was horrible,” he said. “It messed me up psychologically for a couple months.”

But now, he’s started building his flock back up and he’s pivoting his operation. Instead of searching for restaurant clients, he’s inviting people to stay at the farm and learn what he loves about pigeons firsthand.

“I’ve been trying my best to reintroduce people to squab,” he said. “I mean, people in my generation, they don’t know squab. I’m the only person where they would ever hear about squab from.”

Leiber, who also went to culinary school, now operates a farm stay bed and breakfast. People can come learn about squab farming, among other things, and then try pigeon for dinner — perhaps for the first time.