With alleged medicinal properties and a rich, creamy mouthfeel, camel dairy is topping 2024 food trend lists. But where will it come from?

Camel milk is coming to a shelf near you. It may even be there already.

In the United States, a nation dominated by cow dairy, camels might seem like an uncommon milk source. But that is not the case globally.

“Here in the U.S., of course, we just think cow’s milk is drank throughout the entire world,” said University of Minnesota Extension dairy educator James Salfer. “Other areas of the world drink a lot of different milks than we do.”

Camel milk has been a crucial part of people’s diets for thousands of years in Africa and the Middle East. Camels, unlike cows, are well-suited for the arid or semi-arid conditions in these regions.

Now, more and more people in the U.S. want a taste, too. It’s even making lists of 2024’s hot food trends.

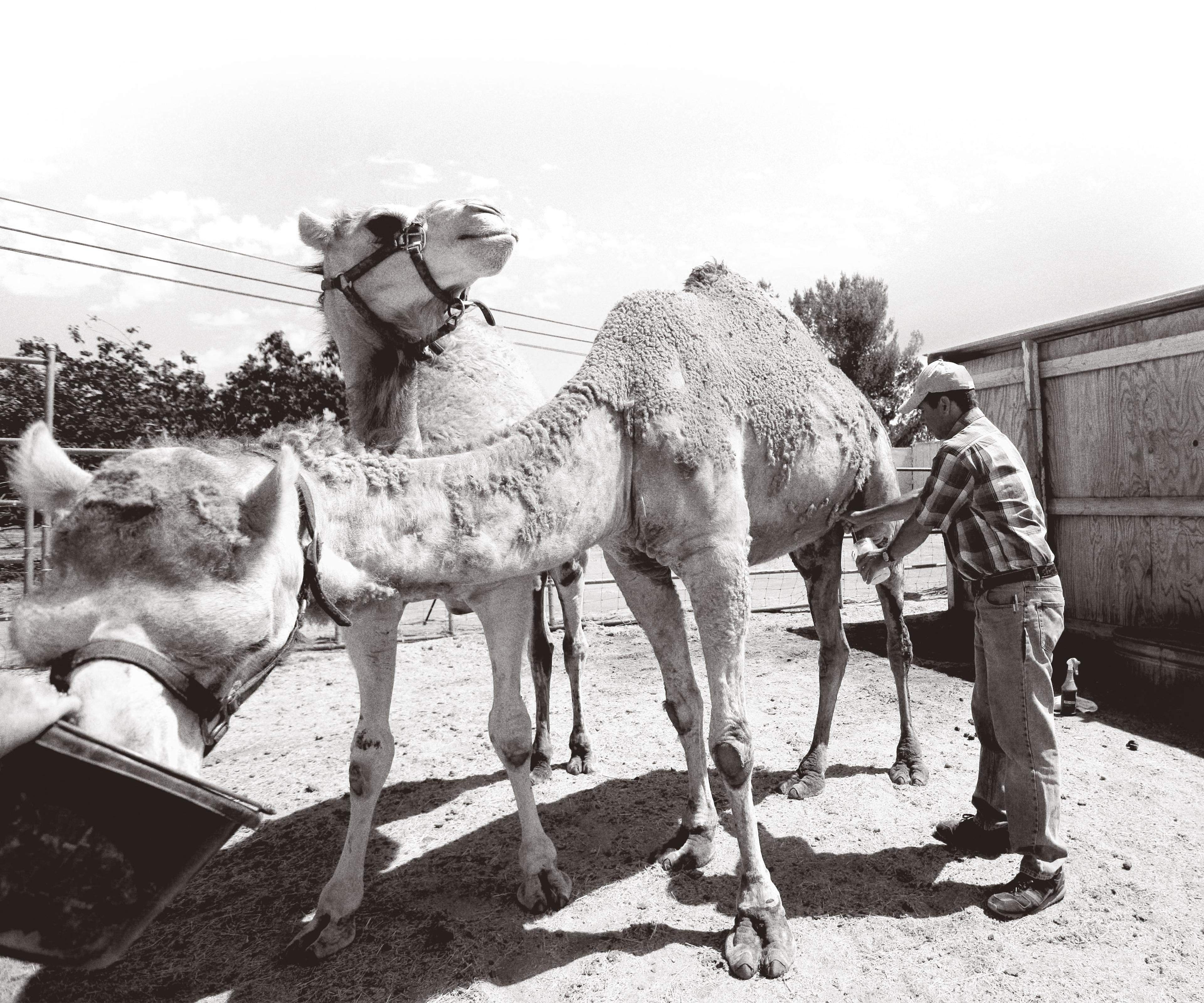

“We get calls all the time from people who are looking for it,” said Luke Blakeslee of River Jordan Camel Dairy in Kosciusko County, Indiana. Blakeslee, who runs the dairy with his wife Amber, doesn’t sell the milk. Instead, they use it to make lotions and soaps, and offer camel fibers for sale, too.

Obviously, Indiana isn’t Africa. A camel farmer in, say, Kenya might keep their camels in dry lots — fenced-off areas with limited vegetation — or other types of primarily outdoor enclosures. In four-season regions of the U.S., outdoor-only wouldn’t be a camel’s ideal climate. “You have to think about how you’re going to handle them in the winter. I’m not sure you could open lot them very well in our weather,” Salfer added.

As far as feed, camels aren’t too different from dairy cows in the eating department, at least on a farm. “They’re not exactly ruminants, but they’re forage digesters,” said Salfer. “For all practical purposes, they ruminate like a cow does.” Camels typically have a less rich diet and need a lot more salt, but all in all it’s comparable.

When it comes to milking, however, camels require significantly more finesse for significantly less output.

“With camels, one of the big challenges is that small-scale production is tricky because there’s a lot that goes into getting a regular supply of milk,” said Blakeslee. In the U.S., cows have been bred to produce more milk. Camels? Not so much. Even in the right conditions, production for a camel will be 15 to 20 pounds a day — or about 2.5 to 3 gallons, according to Salfer. By comparison, the typical cow on a dairy farm in America may be producing closer to 9 gallons.

Camels mature more slowly, have longer gestation periods, and take more time after birthing a calf to start milking — all factors that keep production levels lower.

Along with lower production, camels mature more slowly, have longer gestation periods, and take more time after birthing a calf to start milking — all factors that keep production levels lower.

Further, camel dairies are subject to all the challenges of other dairies, like acquiring USDA approvals, dealing with a perishable product, and shipping their product nationwide, all with less milk to begin with.

“If you don’t have the numbers, then you’re not going to be able to supply a customer base,” said Blakeslee. He and his wife don’t have the goal of a large milk-production dairy.

Another challenge is basic biology — camels don’t make their milk nearly as available as cows.

“Our cows have been bred to naturally let down their milk without a calf around,” said Salfer. “They’ll walk into the milking parlor and they’ll hear milk pumps running and with maybe a little prep, they let it down.”

The milk letdown process refers to the ejection reflex that moves milk from sacs within the mammary glands to the teat of a cow or a camel, where farmers can access it. With camels, the calf must be present or the mom will not let down her milk.

“We’ve really spent a lot of time making sure that the calves are healthy and that the mother and calf are very well-bonded. Because if anything messes that up well, there goes the milk supply,” said Blakeslee.

According to a study published in Animals, camels require only half the water input of cows.

So, how hard is it for the American consumer to find camel milk as it stands today?

“It depends how close you live to a Whole Foods,” said Blakeslee.

The grocery chain carries pasteurized camel milk, and despite the U.S. hosting only two camel dairies that are licensed to sell milk to consumers, it’s reasonably accessible to buyers online. That said, with the limited number of suppliers — there’s one camel for every 18,000 cows in the U.S. — and high costs of production, those who want it have to pay. The cost of a single pint of camel milk online hovers around $20 (not including shipping), compared to just over $1 for the same amount of cow milk.

Camel milk goes for $11.99 at the Middle Eastern grocery market near this reporter’s Minneapolis home. Like the price, I did not find it comparable to cow’s milk in flavor. The camel milk is bright white and has an almost grassy smell. The weight of the milk is heavy on the tongue, silky and thick, more akin to half and half or cream. To the slightly sugared note that cow’s milk carries, camel milk has a more savory offering. Camels require a high level of salt intake, and it heavily presents itself in the milk’s flavor profile. Where cow’s milk has a mostly one-noted, subtle sweet flavor that drops off quickly, camel milk is more complex. The saltiness gives way to an earthy aftertaste that lingers longer than any flavor cow’s milk offers.

Would I say cow’s milk and camel’s are similar, tastewise? No. Would I reach for camel milk again? Yes! For the sake of objectivity, I even shared with my household’s pickiest palettes — my dogs. They couldn’t get enough.

Camel milk has other benefits, too: It is a solid source of vitamins and minerals. In fact, reports have found a serving of camel milk contains three to five times more vitamin C than cow milk. Iron is a prominent mineral in the milk, with six times higher concentration than in cow dairy. It’s low in sugar and cholesterol and is said to be more easily digestible than cow milk for those who are lactose-intolerant. While the potential medical benefits remain unproven, proponents of the healing properties of the milk claim it can aid drinkers with diabetes, asthma, autism, and more.

“Most people who are pursuing camel’s milk are doing it for some sort of medicinal purpose,” said Blakeslee.

“The greatest, the most healthy camel’s milk that most people are pursuing is unpasteurized, and that, of course, you will not find in a store.”

The medicine seekers, typically, are on the hunt for raw camel milk, which is harder to get.

“The greatest, the most healthy camel’s milk that most people are pursuing is unpasteurized, and that, of course, you will not find in a store,” said Blakeslee.

Like cow’s milk — and any other animal’s, for that matter — camel milk is subject to stringent regulations, leaving it a part of the ongoing raw milk conversation. In many cases, to get your hands on the raw stuff, said Blakeslee, “you’d have to have a relationship with a dairy and you’d have to be part of a herd share or private member agreement. And those vary state by state as to what is allowed.”

For example, only Missourians can order raw camel milk to their doorstep from Desert Farms, a web-based company that sources milk from small camel dairies and ships a variety (raw, pasteurized, frozen, powdered, etc.) nationwide.

In addition to potential health benefits, camel milk has deep cultural connections in Africa and the Middle East and holds religious significance for some Muslim communities. In the U.S., these communities are searching for local access to culturally significant foods, like camel milk.

For example, a group of Somali community leaders recently traveled to Camelot Camel Dairy — one of the nation’s largest, located in Colorado — in hopes of starting a similar operation in their state. The group, with the University of Minnesota’s Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships, wants fresh camel milk in Minnesota, which hosts a population of around 76,000 people of Somali descent.

While operating a camel dairy may come with challenges, one potential pro for choosing camel as livestock is sustainability. According to a study published in Animals, camels require only half the water input of cows. On the flip side, the animal’s ammonia emission — a toxic byproduct from the decomposition of animal waste — is just 10-15 percent of cows. Camels are also pals to anyone looking to “clean rangelands invaded by brambles, thistles, and nettles,” the study said, as they will happily eat that up.

Regardless of why consumers go in search of the milk, it seems like more and more of them will be able to find it in the coming years. According to FoodDive, worldwide camel milk sales are valued at $1.34 billion now, and are expected to increase 4.1 percent through 2032.

Could there be a time in the future when we see more camel dairies all across the U.S.?

“You know, almost anything’s feasible. It’s going to be a lot different style of dairying,” said Salfer, “But I think there’s clearly a market for these products.”