Consumption and support is growing for non-pasteurized milk, in spite of public health official’s warnings — what’s behind it?

This spring, Iowa legislators decided to allow small producers to sell unpasteurized milk products directly to customers beginning on July 1. That same day, Georgia started allowing raw milk sales for human consumption. A similar law in North Dakota went into effect in August.

In spite of objections from public health officials, these new state laws are gaining momentum due to increasing consumer demand. The uptick has been driven by a wide mix of factors, from influencer endorsements and skepticism of public health agencies to Covid-related food shortages and growing disenfranchisement with the industrialized food system.

Raw milk sales are now legal to one degree or another in all but four states and Washington, D.C. Residents of 14 states can be raw milk from retail outlets. Some states only allow milk to be sold for pets, while others require a herdshare, a contractual agreement in which customers technically buy a share of the milking herd. A 2022 survey found that 4.4 percent of U.S. adults had consumed raw milk at least once in the prior year.

Advocates claim raw milk is easier to digest and helps to treat or prevent health conditions like asthma, allergies, eczema, and respiratory infections. Beneficial bacteria don’t get killed off during the pasteurization process, as their argument goes.

But public health authorities say there’s little evidence to back these claims, and that many of the perceived benefits of raw milk are linked to living in a farm environment rather than consuming a beverage. Studies on Amish children — raised on unpasteurized dairy — have found that conditions like asthma, allergies, and dermatitis are nearly unheard of in the community, while that hasn’t been found in every raw milk-consuming population. “Some people would have you believe that is because of raw milk consumption, but it’s not,” said John Lucey, professor of food science with University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Dairy Research.

Lucey warns of the potential dangers raw milk can pose, especially for young children and pregnant women, due to potential contamination of dangerous bacteria like E. coli, salmonella, and listeria. “It’s a very strange and interesting process that’s going on right now — I don’t always know the motivation for them to pass these laws and bills,” said Lucey, who grew up on a dairy farm. “From my science point of view, I think this is nuts.”

One study on the link between foodborne illness outbreaks and changes in state law found that between 1998 through 2018, areas where raw milk was legal had 3.2 times more outbreaks than in areas where it was not. But a more recent study found that these raw milk-associated outbreaks have been declining since 2010, effectively decreasing by 74 percent since 2005 in spite of increasing legal distribution.

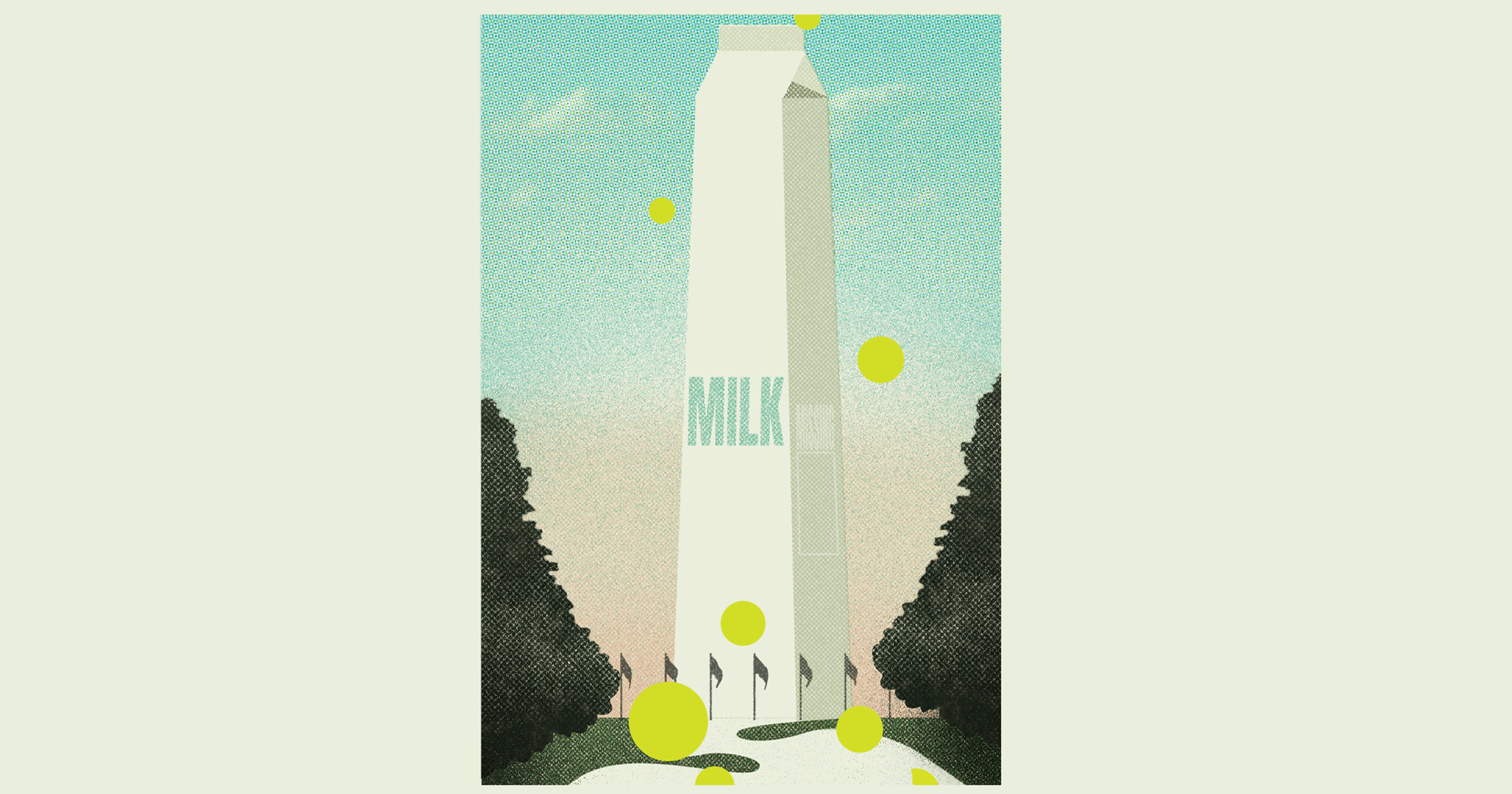

Dairy sales, in general, benefitted from the rise in home cooking that arose from pandemic lockdowns. But raw milk sales have skyrocketed even further — retail sales jumped 27 percent, from $12 million in 2021 to $19.4 million this year, according to data from the Raw Milk Institute.

Raw milk sales have jumped 27 percent, from $12 million in 2021 to $19.4 million this year.

“Covid increased demand and the infant formula shortage also increased demand,” said Pete Kennedy, a consultant for Weston A. Price Foundation, which campaigns for raw milk. “People are going direct to the farm for their food sources as part of a longer term trend that has accelerated in the last few years.”

Last spring, when Abbott Nutrition, the biggest U.S. supplier of powdered infant formula, recalled several of its products, creating a massive formula shortage across the country, some frantic parents began exploring raw milk as an alternative. According to Kennedy, web traffic on a Weston A. Price recipe for raw milk baby formula went up 1,000% percent according to Kennedy.

Raw milk’s burgeoning popularity may also be partly driven by a rejection of our industrial food system, as opposed to specific health claims. “What’s driving [raw milk sales] is people want to know where their food comes from and they want to have relationships in their community with the people who are producing what they eat,” said raw milk producer Sonia Lopez of Two by Two Farms just outside Atlanta.

Georgia is one of the states that recently opened up legal direct-to-consumer sales of raw milk for human consumption. While Lopez already sells the roughly 28 gallons a week of raw cow’s milk and 22 gallons of raw goat’s milk she gets for pet consumption, she won’t be changing her operation for humans under the new law. She can’t afford the costs for licenses and retrofits that would be needed to meet the regulation requirements without scaling up significantly. “Just because I have the demand doesn’t mean I’m going to pop another two to four cows on my 10 acres,” said the eighth-generation farmer.

While raw milk lobbyists have won some major victories of late, they’re still working hard to make it easier to obtain the product in more states. Up next? America’s Dairyland.

Last winter the state’s Farm Bureau flipped its previous stance against raw milk due to increasing consumer demand and voted to support sales at its convention. Now there’s a strong chance that one of the country’s biggest dairy producing states will amend its laws next. “Wisconsin is very much in the middle of change right now,” said Mark McAfee, chairman of Raw Milk Institute. “A bill is drawn up and a sponsor is being sought.”