The imminent arrival of cultivated meat products has led to preemptive bans in prime cattle country, causing friction between supporters and accusers.

When whispers of lab-grown, cell-cultivated meat first hit the media in 2013, a clash between the livestock industry and food system reformers was widely anticipated.

More than a decade later, that clash is unfolding — remarkably, even before lab-grown products have reached grocery store shelves. On May 20, livestock powerhouse Nebraska became the sixth state to preemptively ban the sale of cultivated meat.

Nebraska joined Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Montana, and Indiana as states that have enacted lab-grown meat bans. Florida was the first to pass such a law, and in several cases, companies like UPSIDE Foods already filed lawsuits challenging these restrictions on constitutional and commerce grounds.

Nebraska Governor Jim Pillen, a Republican and hog farmer, framed the law as a measure to “protect and preserve our state’s vital ag industry as well as our consumers” adding that such food products are “unproven, dishonestly labeled.”

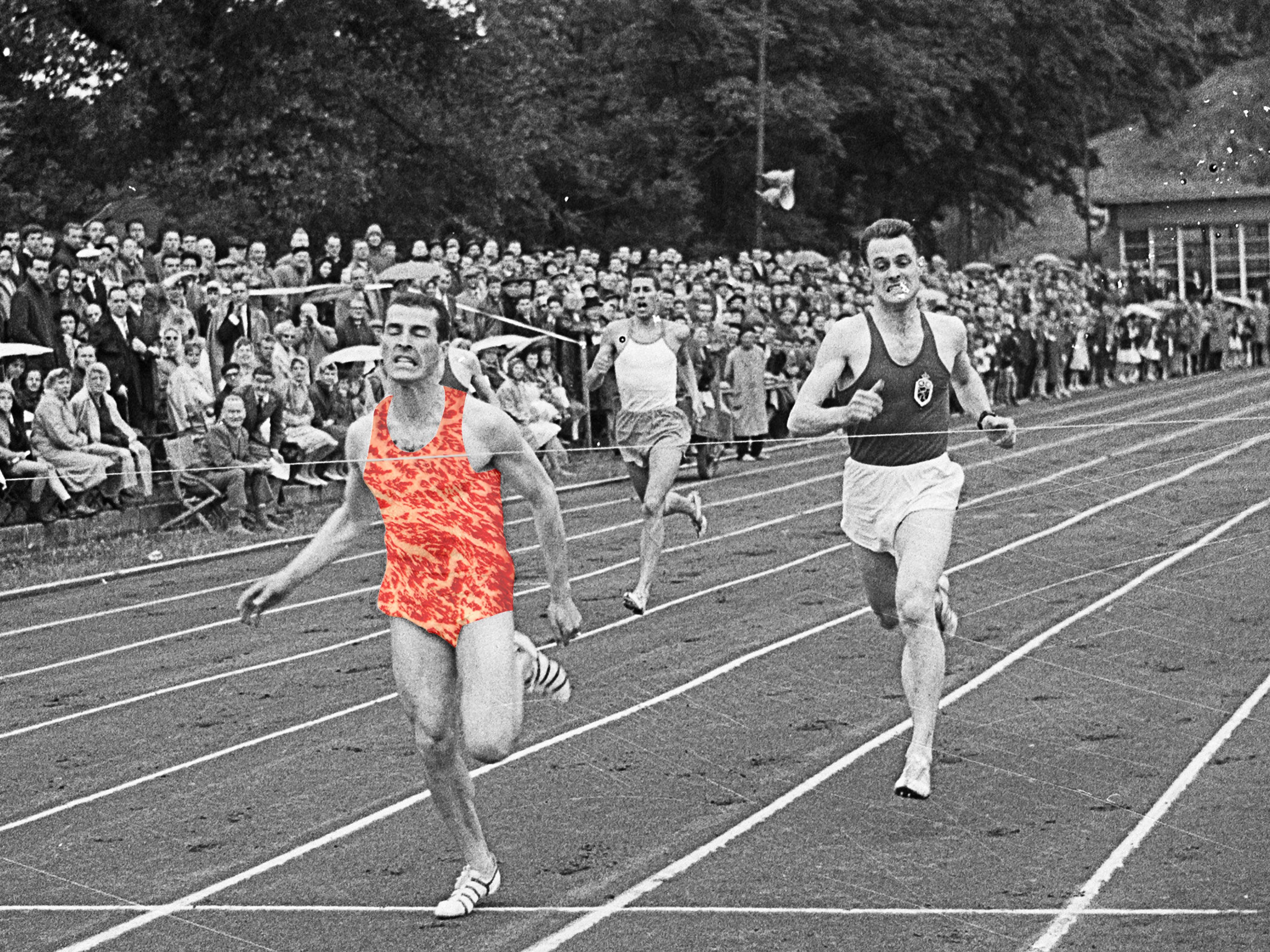

Yet many Nebraska beef producers reject a need for legislative protection, believing livestock can go toe-to-toe against their petri dish counterparts in both sustainability and consumer preference. Statewide industry advocates like the Nebraska Farm Bureau, Nebraska Cattlemen’s Association, and Nebraska Pork Producers have all indicated they do not see such products as any real competitive threat.

While laboratory meat products are indeed made from real cattle cells, they give pause to many. (It’s noteworthy that nearly 49% of Americans say they’re eating more fresh, minimally processed food and 80% check processing levels before buying.) Creating cultivated meat involves growing cells with a nutritional media in bioreactors, producing a highly processed product far removed from traditional beef.

To ranchers like Ron Sealock of Sealock Livestock in south central Nebraska, concern over this reflects a growing consumer desire for wholesome, natural food — something he believes conventional beef already offers. Sealock and his family run a small cow-calf operation, selling feeder calves into the conventional beef market. But while the endpoint of their cattle may be a feedlot, Sealock’s own practices are what he calls “regenerative grazing before regenerative grazing was cool.”

“We’re grazing the ‘dreaded cow,’ but doing it in a way that takes care of the planet. I just don’t buy that what’s made in a lab is going to be better.”

“When I look out the window, I see butterflies, bees, rabbits, bats, and owls,” he said. “We’re grazing the ‘dreaded cow,’ but doing it in a way that takes care of the planet. I just don’t buy that what’s made in a lab is going to be better.”

He believes regulators and consumers alike should be cautious in accepting cultivated meat’s promises at face value. And still, Sealock stops short of supporting a full ban on cultivated meat, “I’m a capitalist. I believe in the free market.”

One of the ban’s loudest supporting voices is the Center for the Environment and Welfare (CEW). Founded in 2023, CEW positions itself as a science-based watchdog group providing issue briefs and commentary to food industry stakeholders, especially those facing pressure from activist groups or investor campaigns related to sustainability and ethics. No clear evidence ties the group directly to beef or meat industry lobbying, but this has been raised as a question by critics.

“Food companies might only get one side of the story when they’re asked to weigh in on controversial issues,” explained CEW research director Will Coggin.

While CEW describes itself as pro-consumer choice in general, Coggin says the group views cultivated meat differently. “This is a food that nobody’s ever eaten before,” he said. “There’s a number of very legitimate questions about whether this food is safe to consume.” CEW’s chief concern is the regulatory pathway itself.

Under a 2019 joint agreement, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) share oversight of cultivated meat. The FDA evaluates the production process and final product under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. USDA then takes over for labeling and facility inspections under the Federal Meat Inspection Act.

“Every cultivated meat product sold in the U.S. must go through a multi-year FDA consultation process, with oversight of everything,” said Madeline Cohen, associate director of regulatory affairs at GFI. “The FDA publishes its findings, the company’s safety dossier and a full scientific memo. That’s far more transparency than most conventional food products receive.”

“Every cultivated meat product sold in the U.S. must go through a multi-year FDA consultation process, with oversight of everything. That’s far more transparency than most conventional food products receive.”

The Good Food Institute (GFI), a nonprofit think tank that promotes alternative proteins as part of a more sustainable food system, defends the oversight process for lab-grown meat as comprehensive and transparent.

“Every cultivated meat product sold in the U.S. must go through a multi-year FDA consultation process, with oversight of everything,” said Madeline Cohen, senior regulatory attorney at GFI. “The FDA publishes its findings, the company’s safety dossier and a full scientific memo. That’s far more transparency than most conventional food products receive.”

During review, companies must submit data showing how their cells are grown, harvested, and tested for allergens, nutritional composition, and contaminants. If FDA determines the data supports safety, it issues a “no questions” letter indicating it sees no need to challenge the company’s conclusions.

But Coggins of CEW points to a whistleblower complaint submitted to the FDA by a former cultivated meat company scientist, which reportedly included product samples with 20 times the lead and eight times the cholesterol of conventional chicken. The complaint, totaling more than 250 pages, has reportedly not been made public despite FOIA requests.

Another concern involves immortalized cell lines, those which are genetically modified to divide indefinitely and commonly used in pharmaceutical testing and never approved in food before. “We’re not saying it’s unsafe,” Coggin said. “We’re saying we don’t know; and that’s a problem.”

Cultivated meat supporters argue this is an overstatement.

“I believe in consumer choice. But these products need to be clearly labeled and thoroughly overseen. Beef can stand on its own.”

“It’s important to remember that cultivated meat is real meat (and) real animal tissue, not a meat substitute,” said Tamar Lieberman, GFI’s senior director of policy. “It’s grown in a controlled, sterile environment … And in many ways, they go further than those for the foods we already eat daily.”

Legal scholars suggest CEW’s framing reflects political dynamics as much as scientific concern. Trevor Findley, attorney and clinical instructor at the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic, noted that states have broad authority to regulate food, regardless of FDA approval.“States have quite a bit of leeway in terms of deciding what foods are allowed to be sold within their state boundaries,” he said, citing the 2023 Supreme Court ruling that upheld California’s pork production standards.

Still, Findley cautioned the line between public health and economic protectionism is often blurred.

Nebraska rancher co-owning Flying Diamond Beef and former chair of international trade with the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association Jaclyn Wilson echoed the importance of state authority and clear oversight. While initially open to the concept of cell-cultivated meat, she said her views shifted after considering the precedent that premature approval or unclear labeling might set.

“I believe in consumer choice,” she said. “But these products need to be clearly labeled and thoroughly overseen. Beef can stand on its own.”

“Why should consumers be asked to eat something when the science just isn’t there yet?”

Wilson noted that her concern isn’t about the science itself but about the process. “If these products are still being developed and studied, then it makes sense that we take the time to make sure they meet the same standards traditional producers have to meet,” she said. However, “Until they’re actually on store shelves, there’s no reason to rush policy one way or another.”

Wilson also highlighted that alternative proteins aren’t immune to market challenges. “Look at the Impossible Beef situation,”* she added. “Their stock share is down to nothing. That’s proof the marketplace will ultimately decide.”

For CEW, the issue remains one of due diligence. “We’re not in a rush,” Coggin stressed. “Why should consumers be asked to eat something when the science just isn’t there yet?”

But supporters say cultivated meat is the result of years of careful development and evolving transparency standards.

“This isn’t science fiction anymore,” says Cohen. “These products are moving through the most rigorous safety frameworks we have for food. If anything, they offer an opportunity to improve how we feed people more safely, more sustainably.”

While supporters and critics remain divided in cattle country, one point of consensus is clear. The public conversation around cultivated meat is just getting started, and the decisions made today could shape food systems for decades to come.

*Note: Wilson was likely referring to Beyond Meat, as Impossible is not a publicly traded company.