Enhanced rock weathering (EWG) is an emerging favorite of carbon market schemes. What does the early evidence say?

When Matt LeBel and his team went out collecting soil samples at the end of September in North Carolina, it was a different experience than usual. Hurricane Helene had just ravaged the southeastern states of the U.S., leaving farmers focused on providing support to communities that had been hit hardest. “We just went out and kind of did things in a way that felt like they could keep their focus on family and supporting the community,” said LeBel, chief of staff at Lithos Carbon.

The team needed to test whether the basalt they’d treated the soil with had actually stored carbon. Lithos sells carbon credits to companies looking to offset their emissions, and with deadlines for end-of-year accounting approaching, LeBel and his team had to act fast. Before the hurricane hit, however, there’d been a drought that had pushed the harvest back, making the fields inaccessible to vehicles, so they had to do the work on foot.

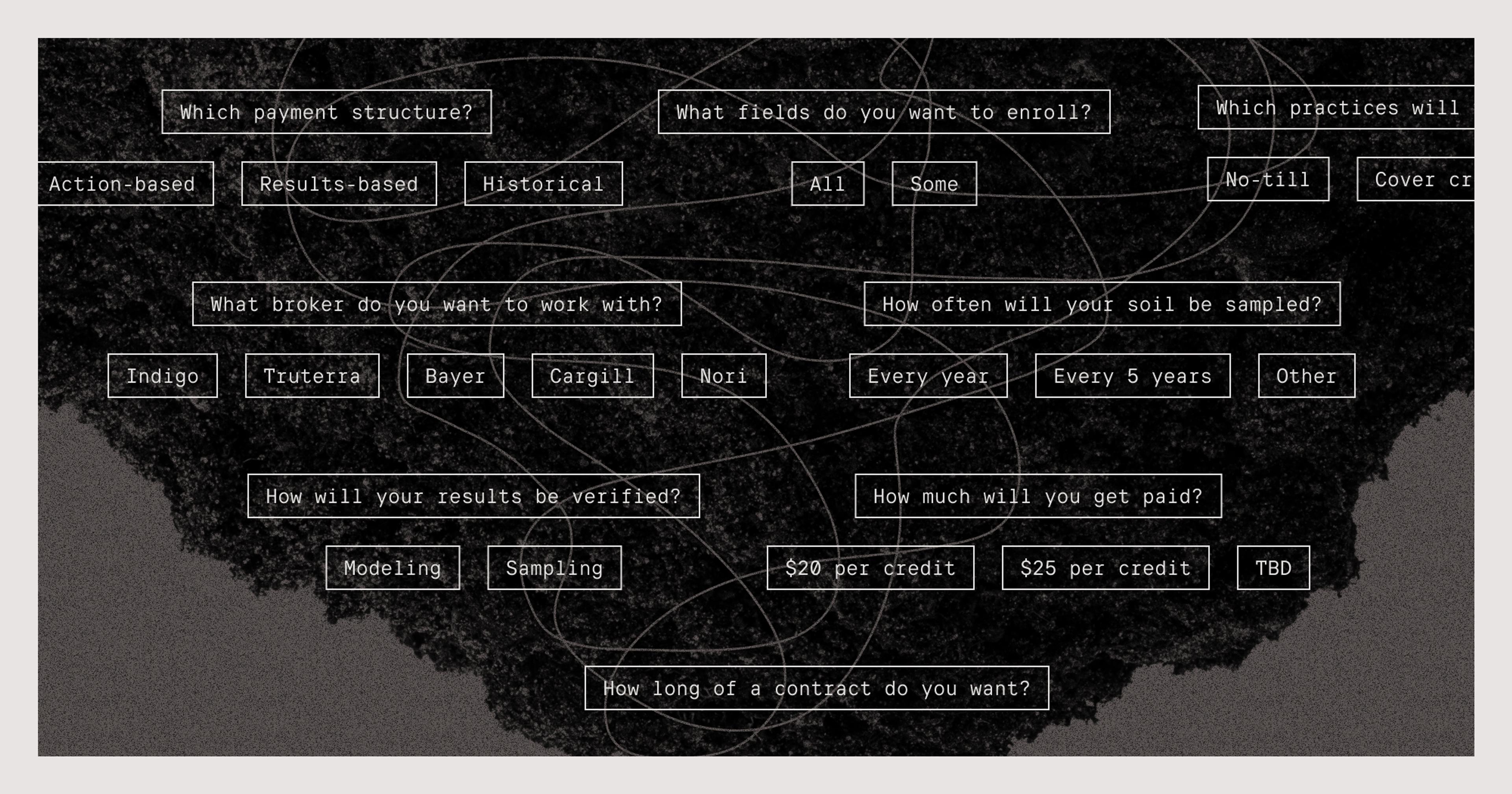

Lithos is one of many companies aiming to store carbon through a process known as enhanced rock weathering (ERW). In May last year, Lithos, alongside four of its competitors, was awarded $1.2 million dollars as a semi-finalist in the Department of Energy’s Purchase Prize, a competition to deliver carbon removal credits to the government. Yet some issue caution on claims of whether the practice can truly store carbon.

When basalt is added to fields and is exposed to water, it breaks down and reacts with carbon dioxide to form bicarbonate ions. These ions contain carbon and are washed away into rivers, lakes and eventually the ocean, where they remain. Lithos adds basalt to farmers‘ soils for free and finances their operations by selling carbon credits to polluters looking to offset their emissions.

“The trade-off is we allow them to put the product on our fields, and we sign off on any carbon credits that they can sell off of our farming,” said Tim Madeiros, a farmer in Newburg, Pennsylvania, who is working with Lithos. They first applied basalt to his fields in July 2023, with the resulting harvest of grass hay in May last year.

Madeiros came across Lithos via a Facebook advert while he was searching for a solution to his weed problems. His farm is organic so herbicides weren’t an option; he instead turned to Lithos and their basalt. Madeiros said that the weed control from ERW has been “very effective” and on top of that his yield increased by 40%.

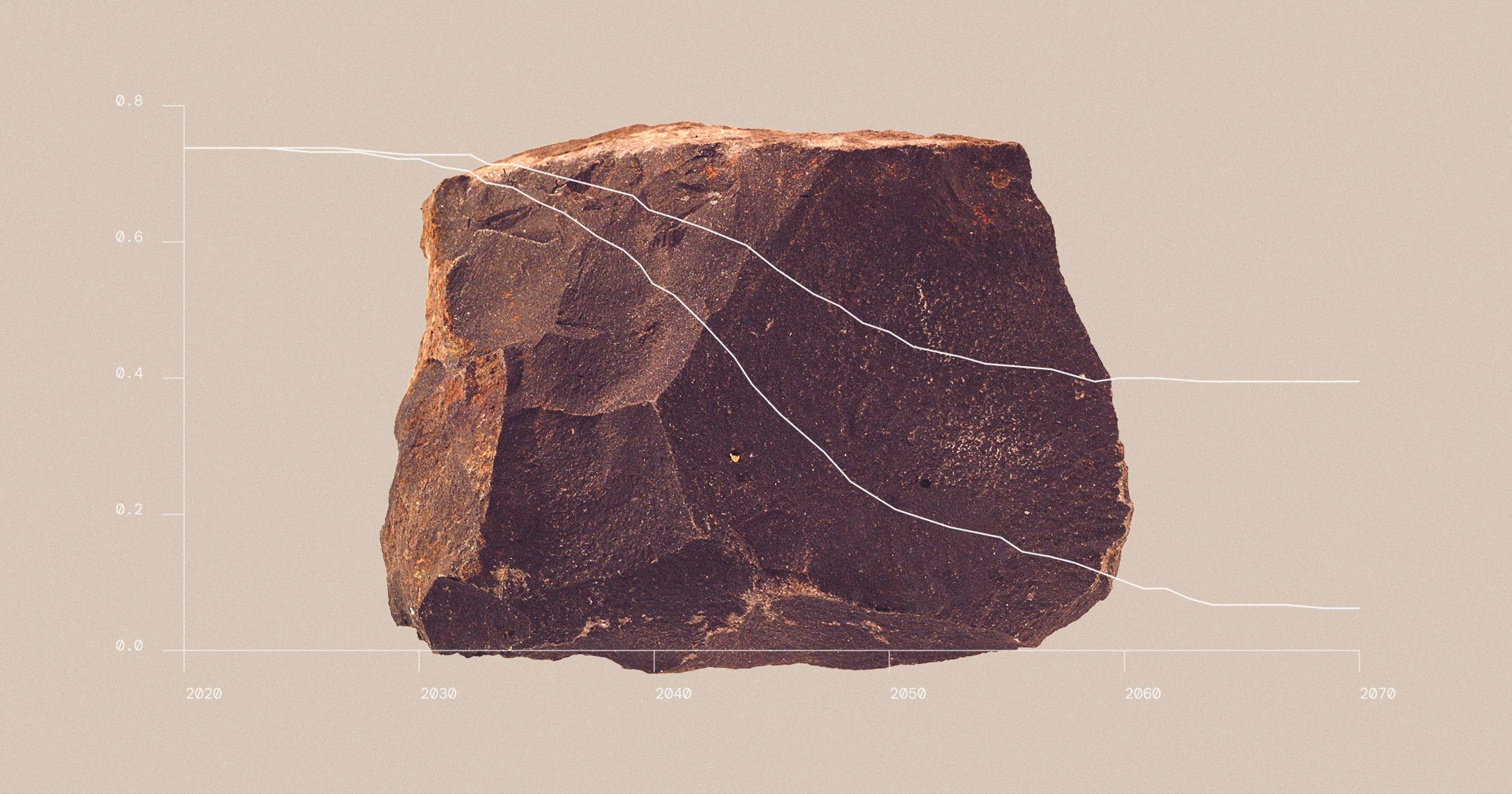

A UK paper published in February 2024 found that ERW can store around 2.5 tons of carbon dioxide per hectare every year and improve crop yields by up to 15%. Another study a year later from the same author found that ERW deployed on agricultural land could sequester 0.16-0.30 gigatons of carbon dioxide every year by 2050. For context, the U.S. emitted 6.3 gigatons in 2022.

“Many studies … are not looking at the net impact of putting rocks on fields for the atmosphere, which is what we ultimately care about in our climate strategies.”

Despite the promising results presented by ERW studies, Freya Chay, program lead at non-profit Carbon Plan, recommends caution, stating that we’re still early in our understanding of the technology’s potential. “Many studies … are not looking at the net impact of putting rocks on fields for the atmosphere, which is what we ultimately care about in our climate strategies,” said Chay.

The study published in February 2024 calculated the carbon storage potential based on the amount of basalt that dissolved — which doesn’t automatically equate to carbon removed from the atmosphere.

Similarly, it’s difficult to generalize, said Chay. Each study has its own design — from the kind of rock used through to the type of soil or the local climate — so results from one situation don’t necessarily apply to others. Differences can arise from “one field to another.” That’s true across time, too: The study found a yearly carbon storage potential of 3.8 tons per hectare in the first year, which averaged out to 2.5 tons per year over a four-year period.

“We need more field trials to understand how general these kinds of responses are,” said David Beerling, professor of natural sciences at the University of Sheffield and lead author of the paper in question. He agrees with Chay that our understanding of the technology is still in the early stages, though he highlights that increases in yield seem to be a consistent result in field trials.

Another consideration is the carbon emitted in deploying the technology. One paper found that it is rock grinding, rather than mining, which has the largest environmental impact. Another found that particle sizes of less than 50 micrometers result in greater carbon sequestration through ERW.

Microsoft, British Airways and the Nigerian government all announced ERW partnerships in fall last year, showing there’s growing interest in the technology.

“I think there is an argument to be made that the commercial sector is running ahead of the science.”

Some have concerns that the business model of selling carbon credits to polluters isn’t doing much to actually address emissions and is instead a way for companies to greenwash. A paper published in November found that less than 16% of investigated carbon credits constituted real emissions reductions, though the paper in question didn’t look into any ERW projects.

“I think a lot of the credits that are used to make public claims to consumers are not backed up by science, and there’s a lot of evidence to support that concern,” said Chay.

Carbon markets are, however, a little more nuanced than that. “Buying credits to make claims that you have offset fossil fuels is very different than buying credits as basically a mechanism for supporting R&D,” she said. She adds that it’s important to take each credit on a case-by-case basis if you want to levy the criticism that it’s a way for companies to greenwash.

“I think there is an argument to be made that the commercial sector is running ahead of the science,” said Beerling. At the same time, he said there are some “very good” commercial companies, and he highlighted Lithos as being “rigorous” in their work.

“We actually go to every farm about every six months and [take a soil sample] approximately every two and a half acres,” said Mary Yap, co-founder of Lithos. The soil samples are then tested against a control field in order to better understand how much bicarbonate has formed.

Modeling is used to understand how the bicarbonate ions move through rivers and into the ocean, which Yap said was studied with academics and is publicly available for scrutiny. It’s possible that when the ions come into contact with acidic rivers — due to excess fertilizer runoff, for example — that carbon can be released again. When accommodating these kinds of issues in their accounting, Yap said they estimate conservatively.

She adds that Lithos currently uses super-fine basalt in their operations, which is a waste product of other mining processes and therefore no new mining or grinding is needed. “We screen all that for purity, for safety, making sure it’s good for our farmers, making sure it’s nutrient-rich,” she said.

Yap said companies like Microsoft and Google “are really trying to reduce their emissions while also buying down removals for the parts that are really hard to reduce.”

Responding to the idea that polluters might use carbon credits to greenwash, Yap said companies like Microsoft and Google “are really trying to reduce their emissions while also buying down removals for the parts that are really hard to reduce.”

Microsoft recently signed a deal with Lithos to permanently remove 11,400 metric tons of carbon from the atmosphere. The software company’s emissions have risen from 12.2 to 15.8 million metric tons of carbon equivalents between 2020 and 2023.

Chay said that on a structural level, “offsets have played a role of relieving structural political pressure on emission reductions,” and that “carbon removal is only useful if we do deep emission cuts.” Yap added that “there’s no way that we’re going to use carbon removal to remove 50 to 60 billion tons of emissions a year.”

For farmer Madeiros, however, the carbon credit side of things doesn’t really matter. He doesn’t believe humanity’s carbon footprint is impacting the Earth. “I would [work with Lithos] again, because simply, it doesn’t cost me anything to do it, and I’m benefiting from it,” he said.

After the post-hurricane collection, LeBel says he and his colleagues at Lithos feel that the kind of hard work they put in is going to be necessary to get the industry off the ground. “There will be more hurricanes, there will be more droughts, there will be more things that impact farmers,” he said. For now, however, things are back to normal: “We’re thankfully outside of that emergency period, we’re back into a world where [the sampling is] more planned, more scheduled, and we’re not as crunched.”