“Enhanced rock weathering” is a carbon removal darling. Farmers like it for other reasons.

The soil on Dan Prevost’s 1,000-acre farm in central Mississippi has a lot going for it. Flush with nutrients from hundreds of years of Mississippi River floods, it’s silty, thick and good for growing cotton, corn, and soybeans, as well as raising cattle.

But it has one major downside: Thanks to a chemical reaction triggered by frequent rainfall, the dark brown earth grows more and more acidic over time. Prevost has to treat it with limestone, which counteracts the acidity, to keep it from killing his crops. Liming is “foundational,” he said, but expensive; when he first started farming six years ago, he could only afford to cover about a third of his fields at a time.

Then, in 2022, Prevost was offered a deal: He could get enough material to meet all his liming needs, at only half the cost. But instead of limestone, he would have to use a different, greenish rock called olivine. Prevost had never heard of it, but he didn’t take much convincing.

“I said if I can get a good liming material at a cheaper price, I’m all ears,” Prevost said.

The olivine came from a startup called Eion, which was able to present it at a heavily discounted rate to farmers like Prevost. When it rains, crushed olivine reacts with carbon dioxide, removing it from the atmosphere and storing it away in a solid form — a process known as enhanced rock weathering, or ERW. Corporations like Microsoft, which recently signed a deal with Eion, are willing to pay a premium to offset their own carbon emissions, subsidizing the cost of olivine for farmers as a result.

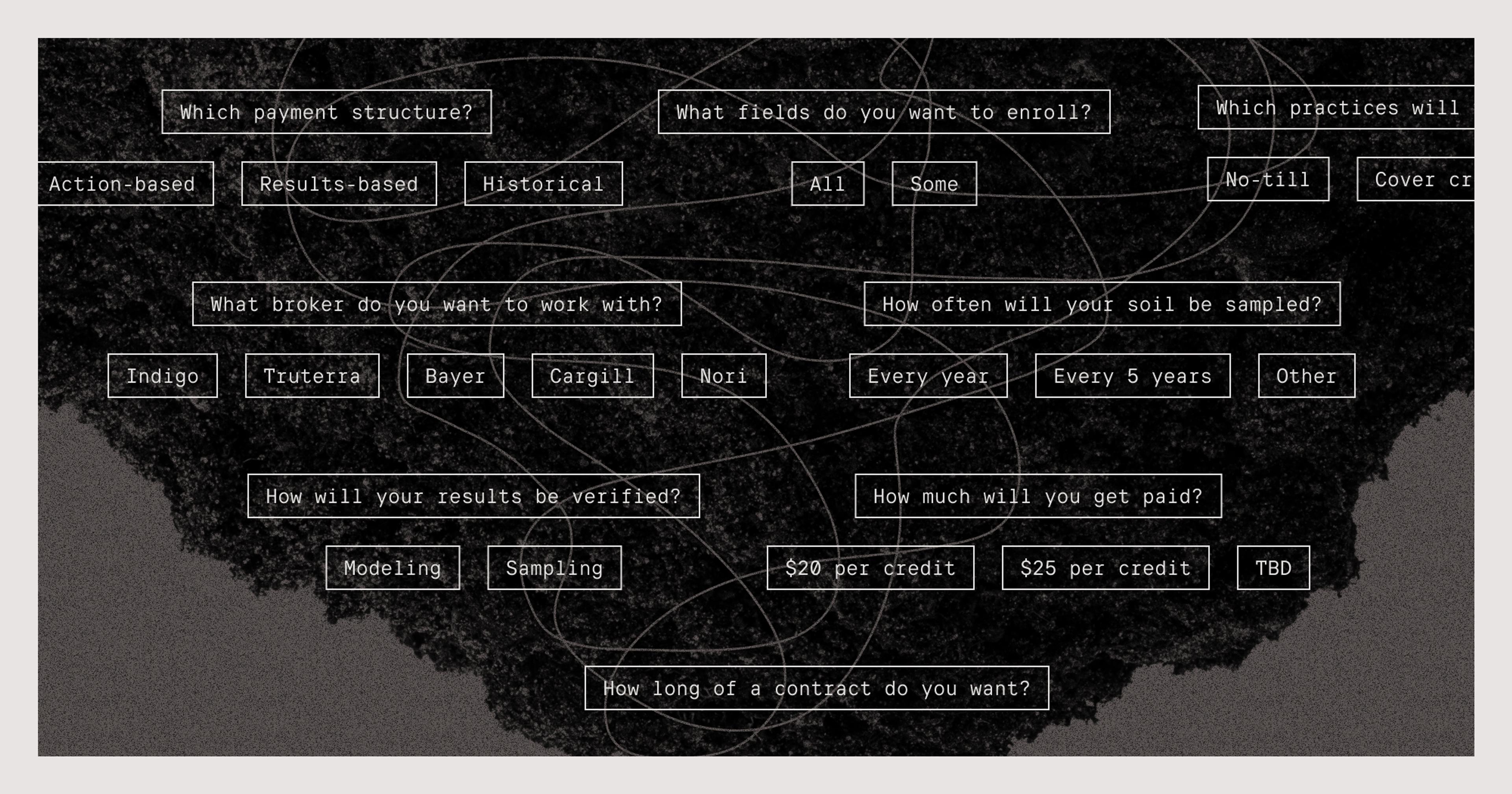

Seeking to meet its own climate goals, the U.S. government is investing in ERW, too; in 2022, the Department of Agriculture awarded $3.1 billion in grants to projects that would develop “climate-smart commodities,” such as crops that sequester carbon through ERW. This rock weathering boom is presenting new opportunities for farmers like Prevost who want to improve their soil health without added costs, even as the future of the carbon markets that are propelling this new technique remains uncertain.

“Farmers aren’t necessarily thinking about carbon marketplaces, but they understand the basic chemistry better than anyone around,” said Noah Planavsky, a geochemist at Yale University who’s working with USDA’s climate-smart commodities program to help farmers learn how to implement ERW.

Many recent efforts to combat climate change have targeted agriculture, which contributes about 10 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. But unlike other “climate-smart” techniques like no-till farming or cover cropping, ERW doesn’t ask farmers to do anything substantially different, said Anastasia Pavlovic, CEO of Eion.

“The practices that we’re fitting into today have been around for ages,” Pavlovic said. Rather than trying to convince farmers to try something new, she said, framing ERW as “replacing or supplementing or reducing the cost of an activity [they] do today … that’s game-changing in the first conversation with the farmer.”

In order to have the biggest climate impact in the shortest amount of time, Eion is targeting large row crop farmers and beef producers, Pavlovic said. The company worked with farmers on about 8,000 acres in the Deep South and is in the process of spreading rock dust on another 8,000 acres in the mid-Atlantic; next year, it plans to expand to the Midwest through a partnership with agricultural supplier Growmark, which will give it access to “millions of acres,” according to a company release.

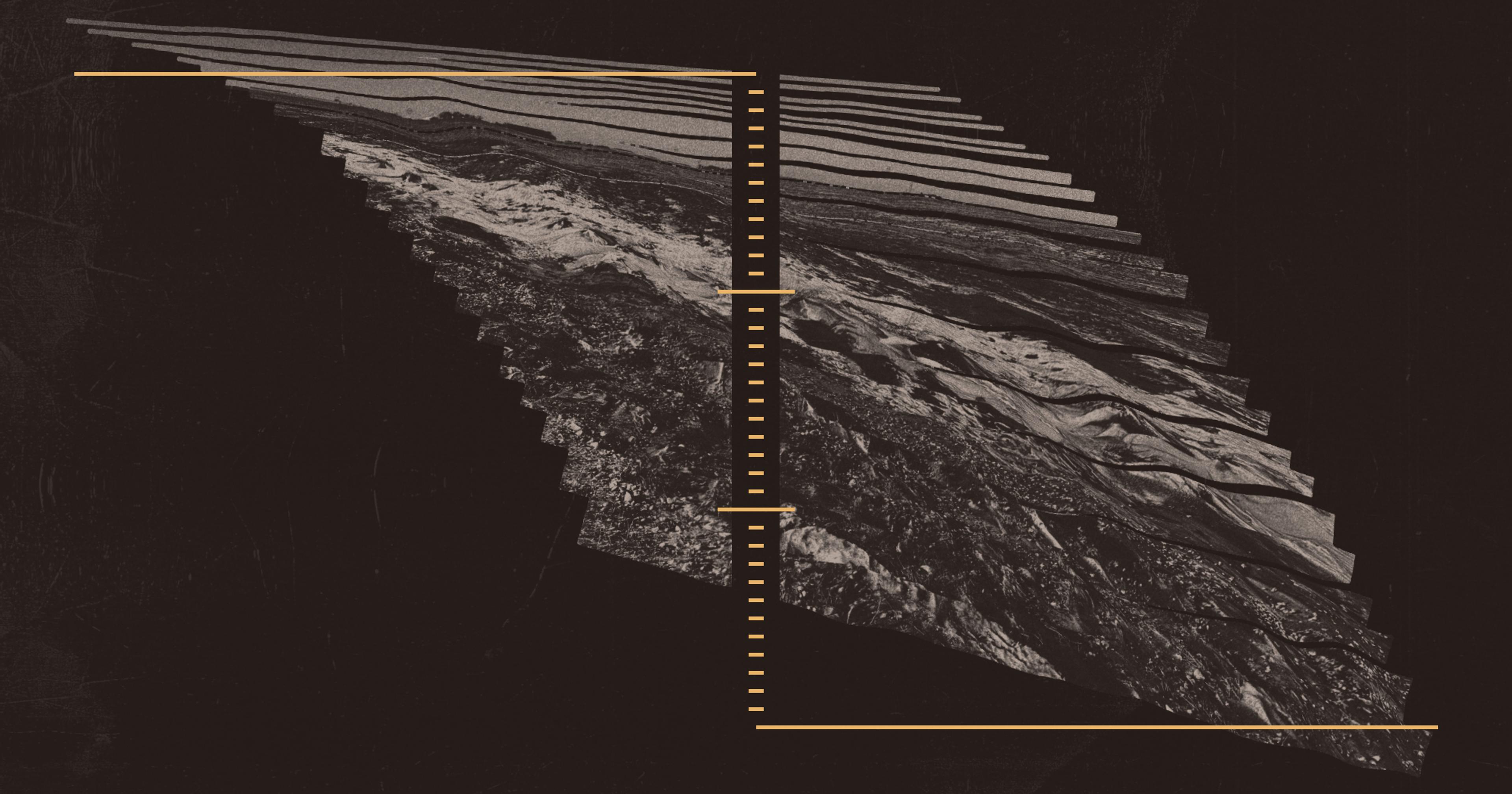

Their work has been bolstered by recent research that has quantified the impacts of ERW on crop yields, as well as the climate. The science behind how rock weathering removes carbon isn’t new; geologists have long known that volcanic rocks like olivine and basalt react with carbon dioxide and water to form new compounds like calcium carbonate, which is swept into rivers and eventually deposited in the ocean.

This process occurs naturally, but slowly, all around the world. ERW was born when scientists found that they can speed up weathering by grinding the rocks into a fine dust, increasing their surface area and having a measurable effect on global carbon dioxide concentrations. Although the amount of carbon dioxide ERW can remove varies widely depending on soil types, crop types, and weather patterns, one four-year study by researchers from the U.S. and U.K found that spreading crushed basalt on corn and soybean fields in Illinois can sequester three to four tons of the greenhouse gas per hectare per year. Their paper, published in February, also reported that ERW increased yields by up to 16 percent compared to liming, and the crops that grew with the help of basalt were more nutritious.

Scaling up ERW application beyond a few test plots will require working more closely with farmers. Many are skeptical about being marketed new products after being inundated with offerings during the agtech boom of the 2010s, Pavlovic said, making a direct-to-farmer model more difficult to sustain. Instead, Eion makes agreements with the distributors who supply amendments like lime, making it easier for farmers like Prevost to work with the suppliers they’re already using. Basalt, the rock that Planavsky and other ERW companies use, also raised some safety concerns; with much of it sourced from mine waste, batches have to be tested for harmful substances like heavy metals.

If they’re able to overcome these hurdles, those who embrace ERW are entering a potentially lucrative market. Under the USDA grant, Planavsky — who co-founded the ERW company Lithos, but stepped away from the company to focus on research — is working with 20 farmers around the country, with plans to expand to 60 in total. He’s focusing on teaching them how to work with the rock dust for different kinds of products, from corn and soy to berries, mixed vegetables, beef, and even honey. He hopes that eventually, farmers can not only get discounts on soil amendments like lime, but actually get paid directly to sequester carbon through ERW, while also being able to market their products as climate-friendly.

“We have way more interest from farmers than we’re able to enroll in the program,” Planavsky said. “It’s a strong sign that these programs resonate with farmers.”

For now, though, the main benefits are still in soil pH management. Acidic soils, which have always been a problem in parts of the U.S. like the Deep South, are now growing more common nationwide due to extensive use of nitrogen-based fertilizers. Basalt and olivine are good at combating this; Prevost saw his soil pH rise by 0.3 to 0.5 points per year after applying olivine. His yield grew too, by about 27 bushels per acre in cornfields that received the crushed rock over those that didn’t. The corn that grew in olivine-treated soils was a darker green, and looked healthier and more vigorous, he said. He was able to double his ERW-treated acreage in 2023, and even introduced some of his neighbors to it.

Despite the benefits for soil health, the future of ERW is uncertain. Substances like olivine are rare in the U.S. and need to be shipped in from Norway; basalt, while more common domestically, is still costlier to procure than lime, which has an established supply chain for agricultural buyers. The math works out right now because companies like Microsoft or agencies like the USDA are willing to pay farmers to remove carbon, lowering costs of these rocks. But under a new presidential administration, which has promised to slash any mention of climate change from federal programs and pull the U.S. out of the landmark Paris climate accord, public funding for ERW will likely dry up; private financing could follow if companies decide they no longer want or need to reduce their carbon emissions.

This year, Eion shifted its focus to farmers in the mid-Atlantic under the new deal with Microsoft, and Prevost was unable to secure any olivine as a result. He doesn’t need to lime his fields again until 2026, and hopes that by then he’ll find another source.

“We need buyers of carbon to make this whole thing work,” Prevost said. “Whoever is buying these credits, they need to buy more.”