The need remains extraordinary as difficult assessments and treatment continue.

Shortly after the massive Smokehouse Creek fire had ravaged the nearby landscape near Canadian, Texas, Andy Holloway went to meet a rancher.

“He collapsed into my arms, sobbing,” said Holloway. “He lost hundreds of mother cows … only one survived.”

Holloway, county extension agent for Texas A&M AgriLife in Canadian — population of around 2,500 — said the devastation was too sudden and too much to bear. Most of those affected, understandably, do not want to talk about it.

“I’m not too old and too big to admit it, but there’s been a lot of tears with all of this,” he said. “I’ve had to stop my pickup and just get out and weep. These are people we go to church with and see at the grocery store.”

Holloway said the Panhandle-centric fire burned 70% of 600,000-acre Hemphill County, home to Canadian, and said that out of the county’s estimated 22,000 mother cows, between 6,000 and 8,000 died in the inferno. Holloway described it as “a warzone,” while Texas Rep. Ronny Jackson of the state’s 13th District said in a Twitter video that, “There are dead animals everywhere.”

The overwhelming number of injuries contrasted dramatically with the number of veterinarians who could respond quickly across a vast swath of charred Panhandle ground. With an acknowledged shortage of rural veterinarians nationally, animal specialists from outside the area swooped in to collaborate with local vets whose plates were quite full. They made the difference, in so many cases, between animal life and death.

Small towns‘ infrastructure, including Canadian’s, were largely spared, while farmhouses and ranches around them were lost, said veterinarian Deb Zoran, professor of veterinary medicine at Texas A&M and director of its Veterinary Emergency Team (VET). The team deployed to Canadian for 10 days as part of a seasoned group of university professionals who helped triage emergency care through five counties.

Three veterinary practices operate in the immediate Canadian area. One was destroyed by the fire, though that vet continued to help local residents. Zoran said veterinarians from the towns of Miami, Wheeler, and Lipscomb also joined forces to help.

“It’s a bit of a delicate dance, for in the immediate aftermath, we were there to give local veterinarians a hand as support, and not to take business away by doing things they can do for their clients,” Zoran said.

“It’s a bit of a delicate dance, for in the immediate aftermath, we were there to give local veterinarians a hand as support, and not to take business away.“

According to a Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences news release, the VET team estimated visually checking 672 cattle and examining or treating 271 animals: “cattle, horses, donkeys, dogs, cats, a pig, and a goat.”

Zoran said “the first wave” were those so badly burned, they needed to be euthanized. Others were burned and could be cared for. Still others with hooves damaged by heat, and burns to lower legs and feet, sometimes showed dire injuries after four to seven days. If hooves slough off from heat, the animals can’t stand and must be euthanized. On top of that, much of the livestock suffered from lung damage.

“Respiratory injuries are terrible for cattle, and some may be culled and sent to slaughter,” Zoran said.

“Chemicals released in the smoke can cause inflammation of the trachea and lungs, which can eventually lead to respiratory disease,” wrote the Texas Animal Health Commission in an email. “The long-term effects on animal health cannot be predicted,” it said.

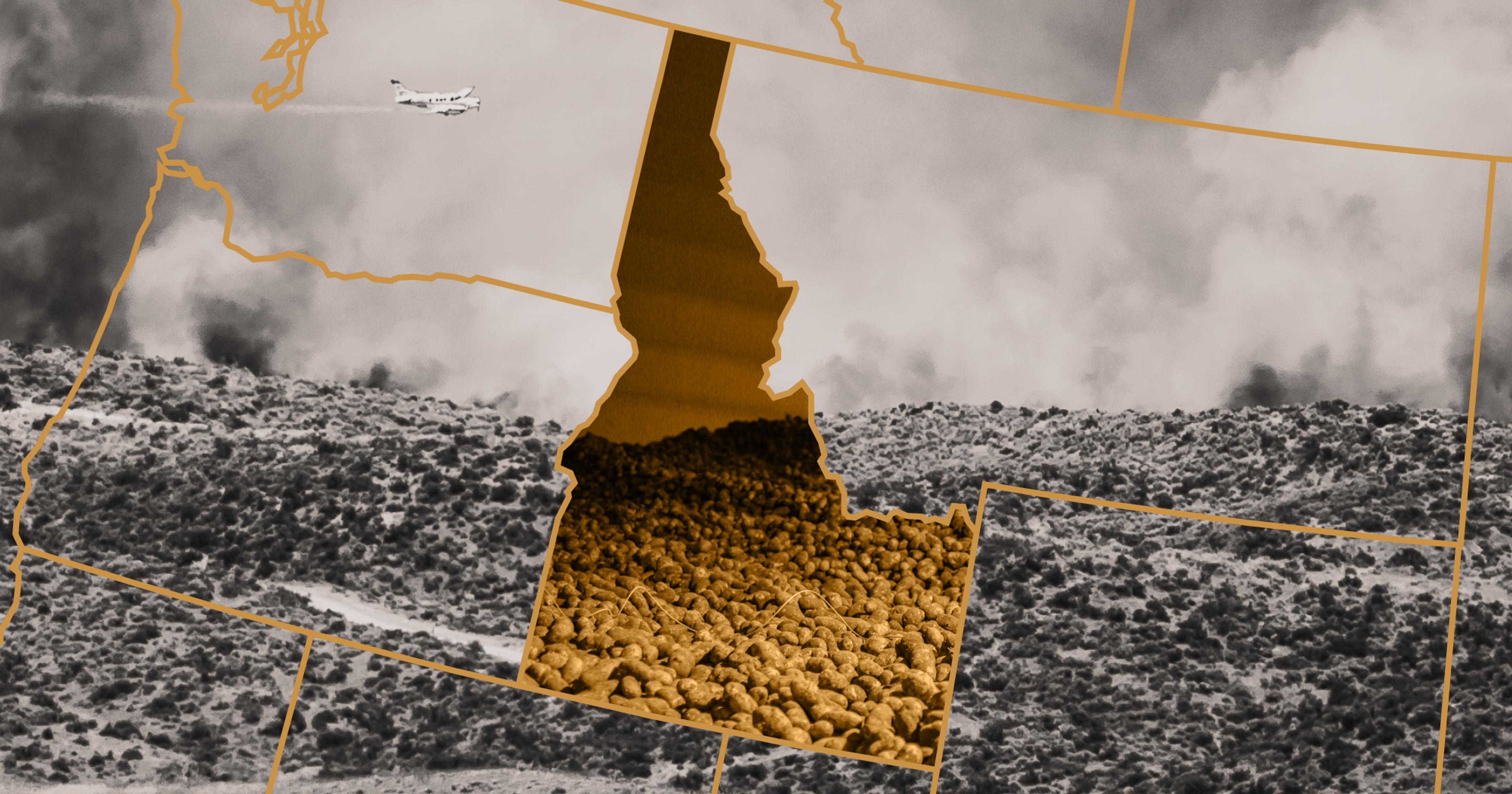

Multiple voracious fires wreaked havoc on the Panhandle at once this year. That includes the two largest, the Smokehouse Creek and Windy Deuce fires, along with the 687 Reamer fire, Grape Vine Creek fire, and Magenta fire.

Texas A&M Forest Service said that, at time of publication, 1.06 million acres had burned in the Smokehouse Creek fire, the largest in the state’s recorded history, and the second largest in U.S. history. More than 144,000 acres had burned in the Windy Deuce fire, both fires having moved through multiple Texas counties and into Oklahoma.

“Just because it’s not a dog or cat on the living room couch doesn’t mean cattle weren’t cared for or weren’t emotionally important to these people.“

For ranchers who need to find help or explore disaster relief options, or readers who want to donate money or supplies, a comprehensive list of vetted options is available at AgriSafe, Texas Farm Bureau, and Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. Holloway said there’s also a Venmo: @FireReliefFund. General needs include hay and hay-hauling equipment, fencing supplies, salt blocks, and cattle cubes comprised of at least 20% protein.

Texas Farm Bureau director of communications Gary Joiner said the Canadian area lost 120 miles of power lines and that disabled water pumps, creating another set of formidable challenges.

Ranchers with available land have responded. “They’re reaching out saying, ‘I have land available, I have corrals,’” he said, stressing the need for fencing supplies. They’re needed not just for cattle, but also horses, and sheep and goats that may be 4-H projects.

Pets have been part of the loss equation, too. Loretta Tebeest, co-founder and director of the nonprofit animal rescue Gracie’s Project in Amarillo, Texas, traveled to Fritsch in Hutchinson County to rescue injured pets. She said those efforts were confusing sometimes, since some farm pets roam free outside all the time.

“It was a workday, and a lot of people weren’t home, so there wasn’t time to remove any animals,” said Dana Huff, publisher and editor of The Eagle Press in Fritsch. Her closest friend lost three dogs in the fire, and another friend lost four, but her two cats ultimately returned home.

On thousands of Panhandle acres, animals run for their lives, and it can be weeks until they’re found, Zoran said. “Cats can be smart and wily, hiding in culverts when fire comes.”

“When circumstances go beyond our control, it can sometimes tip the scale beyond our own coping mechanisms.”

With so much sorrow to process during and right after the initial event, ranchers and farmers will find “it all reverberates for a while,” said nurse practitioner Tara Haskins, total farmer health director for the AgriSafe Network and an advanced holistic nurse focused on mental health programming.

“The destruction of animals can translate into trauma,” Haskins said. “This is brought on by the massive depopulation, the conditions of those still suffering, the triaging of animals, removal of carcasses, and the burnout — producers manage all these moving parts, which can include financial devastation.”

She said ranchers feel an obligation to care for their animals, even when ultimately raising them for food. “They feel a connection with that, and they’ve invested so much time knowing it provides a livelihood for their family. Then when circumstances go beyond our control, it can sometimes tip the scale beyond our own coping mechanisms.”

All of it could be “incredibly, horribly traumatizing,” said Zoran. “Just because it’s not a dog or cat on the living room couch doesn’t mean cattle weren’t cared for or weren’t emotionally important to these people.

“Now, in one fell swoop of Mother Nature going crazy, that’s been lost,” she continued. “But with Mother Nature, life will find a way.”

Ed. Note: AgriSafe operates the AgriStress Helpline at 833-897-2474, a free, confidential crisis and support line. AgriStress specialists understand and empathize with the culture, stressors, and lived experiences of agriculture workers.