California just got its first new farm bureau in 40 years, in its smallest and most population-dense county. It’s not totally clear why.

The landscape of San Francisco — steep, packed, and often wet with fog — is at odds with standard ideas of farmland. You won’t find the sprawling pastures and acreage of crops that decorate California’s interstate highways, nor the thousands of rows of vines in nearby wine regions. But upon closer look, scattered among the old Victorians and autonomous taxis, the not-quite 50-square-mile city holds roughly 100 urban farms and community gardens, plus a decently sized ag tech sector. So it only seemed logical to State Treasurer Fiona Ma that the city get its own Farm Bureau.

The San Francisco Farm Bureau (SFFB) — the first new one chartered in California in nearly 40 years — was the passion project of Ma, who initially sought to support California’s food system following the supply-chain hysteria of Covid-19. After committing herself to understanding the state’s vast agriculture sector and touring over 200 farms, Ma was surprised to learn that her home county of San Francisco didn’t have its own bureau. Only one other county in the state — Alpine, located within the Sierra Nevadas — was not represented by a bureau.

“There was some skepticism, as you can imagine,” Ma said, describing the day she and a handful of industry contacts proposed the chapter at a delegate meeting in Reno. “You know, who are these San Francisco people?”

Given that the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industries combined employ less than half a percent of San Franciscan workers, this chapter’s focus is likely to be different from others in the state. Ma, who previously represented San Francisco in the California State Assembly, hopes the initiative will be a far-reaching support system for both aspirational and practicing growers across the city, with a particular emphasis on youth educational programs.

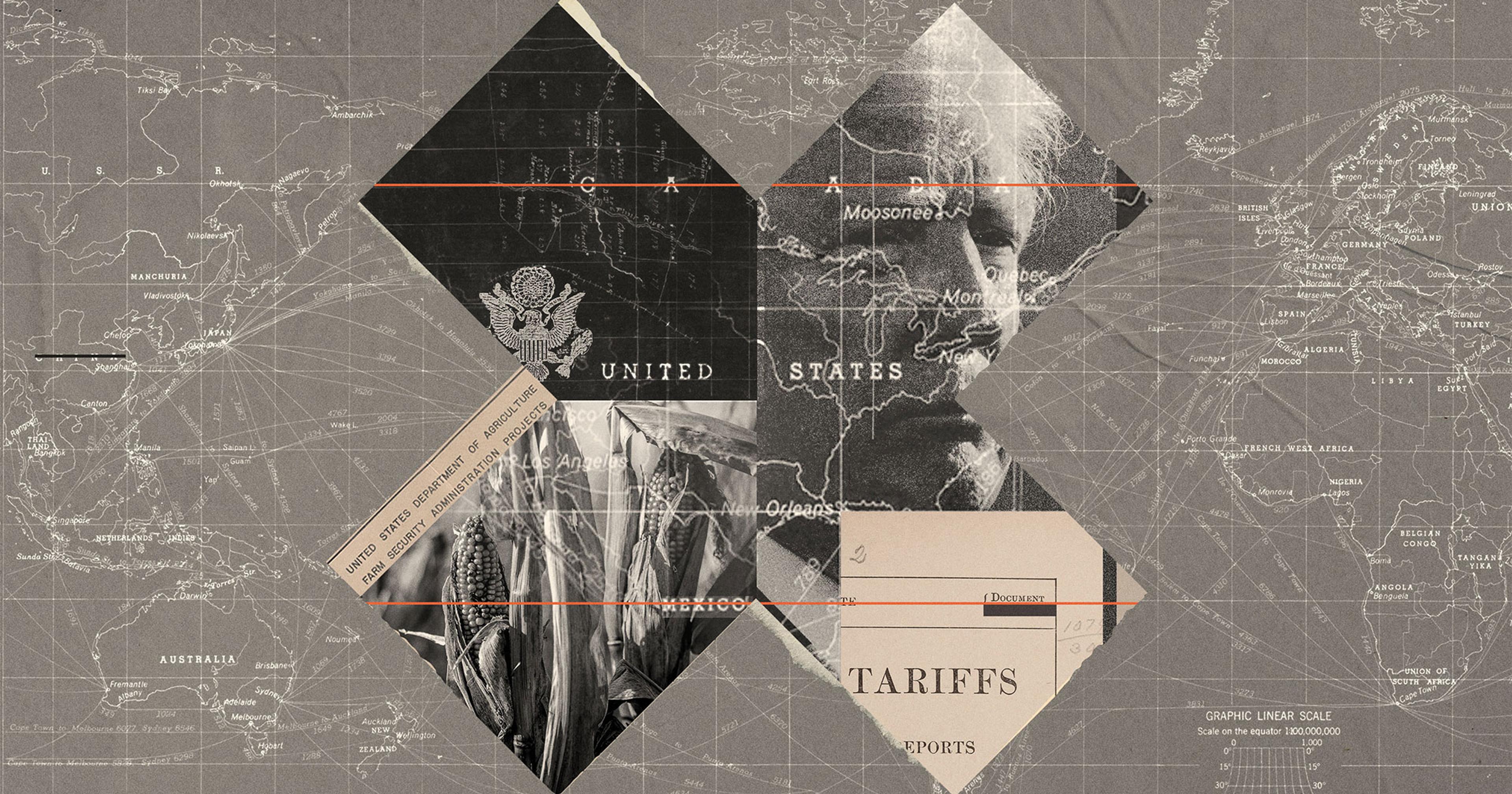

California farm bureaus typically work in the policy realm, attempting to incorporate the needs of local farmers and help them adjust to changing regulations.

But the farmers in San Francisco County may not share the same concerns as those in more rural regions of the state — and in some cases, Bay Area-bred initiatives have been a source of contention in other agricultural communities. A bill in nearby Sonoma County seeking to outlaw “Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations,” or, euphemistically, “factory farms,” was spurred by Berkeley activists. The Bay Area also contains the first cities to ban the sale of new fur, now a statewide policy.

“A lot of the animal laws start in San Francisco.” said Ma. “So some [state farm bureau delegates] were really skeptical of what our mission, vision, and ulterior motives were,

The farming industry is one of the most powerful lobbies in the U.S. Across the country, farm bureaus have been criticized for throwing their dollars behind social and political causes — such as election security and education — that have little to do with farming. The Napa County Farm Bureau, for instance, which oversees the region’s $9 billion wine industry, was subpoenaed late last year for records related to its political action committee, a PAC that has historically supported winery developments and pro-development politicians.

“There was some skepticism, as you can imagine. You know, who are these San Francisco people?”

So what do San Francisco-based farmers want? Christopher Renfro, founder of the Two Eighty Project, an urban farming and mentorship organization, said that if the SFFB can provide some municipal support, farmers in the city will have more time for community building. The small-but-mighty community is “definitely connected, but also definitely fragmented in a way that feels like everyone is scrambling for the same resources,” he said.

Renfro grows grapes on plots of land dispersed throughout the city and surrounding area, some of which can be seen from Highway 280, and also mentors youth. “That’s what I hope they’ll be there for: Here’s a loan or a grant that we can help you get. Here are the people that’ll help you file everything so that more farming is happening.”

With little to no space, some seasoned farmers have been tapped to oversee the implementation of rooftop farms in the Bay Area. In several cases, these farms have become successful ways to address food insecurities in the area (especially during the pandemic), help mentor and place local youth in leadership positions, and address the climate crisis. However, San Francisco’s steep pricetags remain a barrier to many.

Ma said the bureau is going to help the city’s growers stay on top of compliance. “It’s not easy to do any type of business here in California. The regulations are constantly changing and getting more and more difficult. Everything is costing more here in the states, the different agencies, they are auditing more, requiring more reporting,” she said.

“That’s what I hope they’ll be there for: Here’s a loan or a grant that we can help you get. Here are the people that’ll help you file everything so that more farming is happening.”

This spring, Ma was joined by San Francisco Mayor London Breed and Blong Xiong, the USDA Farm Service Agency’s executive director in California, to encourage community gardens around the city to register with the USDA and utilize the resources at a newly announced urban agriculture service center in Oakland. (Xiong did not respond to requests for comment.)

Beyond paperwork, Renfro said he’d love to see some of San Francisco’s open spaces turned into more community gardens — a sentiment echoed by many of his farming peers.

Land is the city’s tightest resource, whether you’re farming or not. Because of this, San Francisco’s agricultural scene differs greatly from even that of other urban California counties. California’s most populous county, Los Angeles, has over 750 farms across 69,224 acres, according to data from the USDA. By comparison, San Francisco has seven farms over 127 acres. However, the average market value of the land and facilities is significantly higher in San Francisco than the rest of the state at an average of $48,425 per acre, second only to Napa ($61,295).

Much of San Francisco’s agriculture is performed through its 42 community gardens, some communal and some individual. The waitlist for an individual plot is currently several years, according to San Francisco Recreation & Parks, which oversees the gardens. The agency owns 4,100 acres and some 200 parks across the city.

“It’s funny how we’re not thinking about how people need green space beyond just sitting in it — we also need green space to get your hands dirty, green space to actually feel like you’ve worked,” said Renfro. “During the pandemic, everybody got super into feeding themselves. A lot of people got really into the idea of baking their own bread, doing things from start to finish. And I think that’s something we don’t promote anymore, learning how to do something from the beginning of it all the way to its finished product.”

“I think the tech sector understands that there are three things that we need as humans. We need water, we need food, and we need air.”

In order to hold a board seat, one must derive most of their income from agriculture which, in San Francisco, can be quite difficult. However, those who live in the city — even if their farming operations are elsewhere — qualify. Currently, SFFB has 41 members, 13 of whom are directly involved in agriculture, according to its president, Gary Sosieth.

“While about 30% of our membership consists of agriculture members, many are like me: We farm in other areas of the state, but call San Francisco home full- or part-time,” said Sosieth, an advisor for USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance and the former mayor of Turlock, a small town in California’s Central Valley.

Ma said another goal of the bureau is to integrate the city’s ag tech sector with its more traditional growers and gardeners.

“I think the tech sector understands that there are three things that we need as humans. We need water, we need food, and we need air,” said Ma. “We need to be able to feed people, more people, even if we don’t have enough water. So I think for people who are focused on solving everyday problems, food has to be one of the top line items.”