Indoor agriculture doesn’t get more local than small vertical farms right where people live and work. But the future of these farms is more closely tied to conventional urban farming than the wider vertical farming industry.

The first time I visited Little Wild Things City Farm, smoke from wildfires hundreds of miles away clogged the air, the AQI hovering near 300. When I arrived, no one was there. They had sent their farmers home early to avoid the worst of the smoke; many walk to and from the farm’s location in Washington, D.C.’s Trinidad neighborhood. But the farm itself wouldn’t be affected by the smoke and other increasing extremes of climate change: It was all indoors.

Little Wild Things is a 3,000-sq ft, windowless second-floor space, rented from the hardware store downstairs. Rows of microgreens growing out of dirt are stacked five levels high, and you hear the constant whir of a hydroponic tank pumping water to two rows of edible flowers. It’s a commercial operation, one of several small vertical farms in the D.C. area.

These farms — and others like them across the U.S. — operate out of spaces very different from both conventional urban farms and large vertical agriculture operations. They’re neither scrappy, low-acreage outdoor lots run by schools and nonprofits, nor are they the slick enormous operations that have been the visible face of vertical farming.

Most of the growth — and the investment — in vertical farming in the past few years has been in the latter: mass-production businesses growing hydroponically in football-field sized warehouses.

It’s been sold on a compelling premise. By lowering the amount of produce shipped from California and globally, these farms cut transportation costs and emissions, and promise fresher, more nutritious food closer to large population centers year-round. They also boast about their protection from the elements, and how little water and land they use compared to a conventional field.

Inside, Little Wild Things is protected from the “freak accidents of nature” that can ruin a crop, farm manager Brittany Gallahan said, and workers aren’t exposed to UV radiation for long hours under the sun.

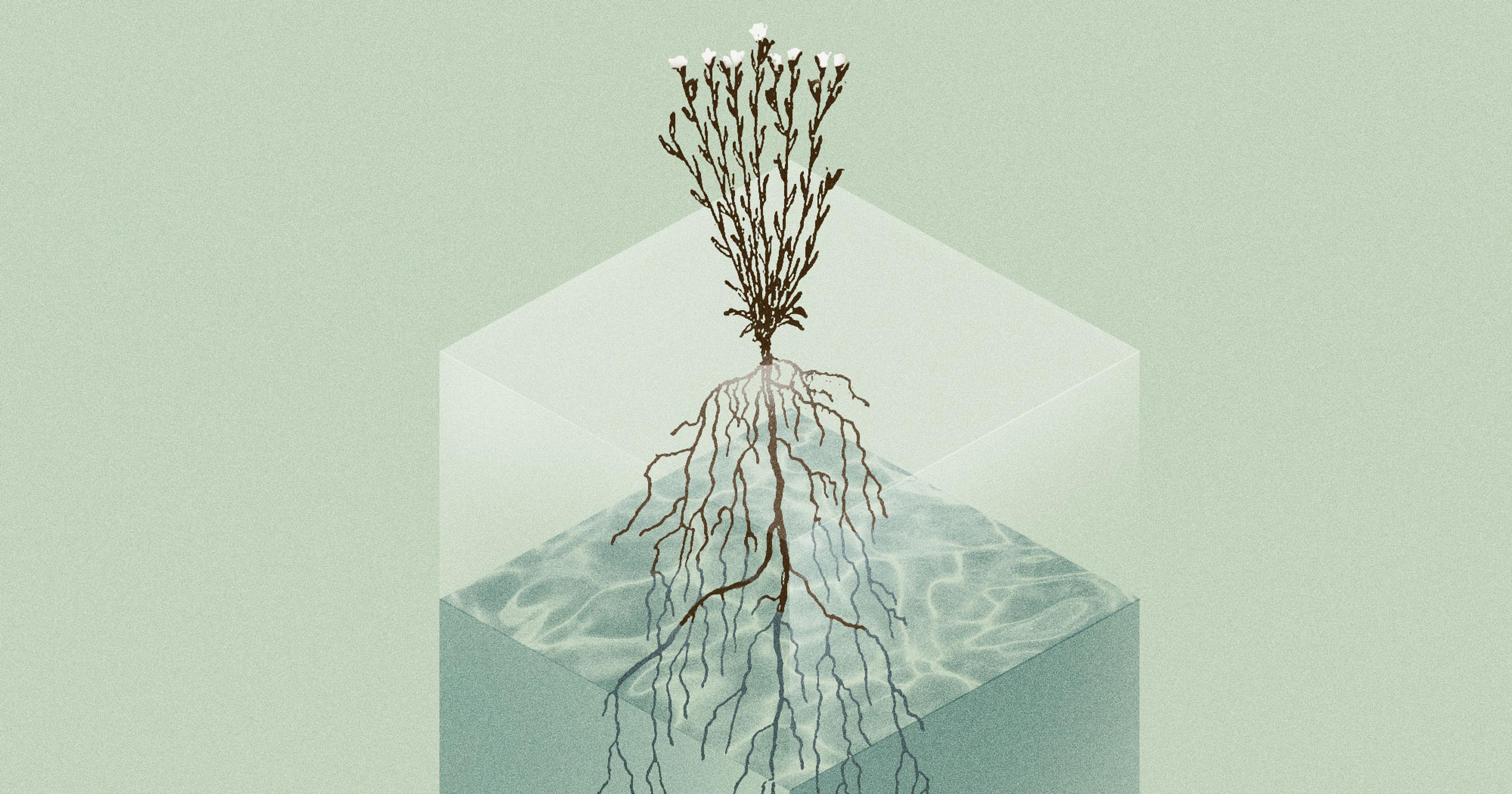

Smaller vertical farms also offer the shortest-distance between farm and consumer possible. Across the river from Little Wild Things, Area 2 Farms delivers its produce to CSA members within a 10-mile radius, but the larger goal is to place many more small vertical farms as close as possible to where people live and work.

“Our whole entire mission is to move the farm, not the food,” Area 2’s community partnerships manager Jackie Potter said.

Little Wild Things is protected from the “freak accidents of nature” that can ruin a crop.

Housed in a small industrial strip across from a dog grooming business and an auto body shop in the densest suburbs of Virginia, underneath Area 2’s two-story high ceiling are several vertically stacked, mechanical moving scaffolds the company calls a silo. As a first step to its expansion, Area 2 is planning to place a display version of the silo in Union Station, Amtrak’s hub in downtown D.C., ultimately hoping to turn it into a working farm.

The climate impact of vertical farms is complicated and widely differs from farm to farm. While the produce typically travels far shorter distances, vertical farms consume a giant amount of energy compared to conventional fields.

While some indoor farms either purchase zero-emissions energy or install renewables onsite, the carbon pollution impact of high electricity usage is otherwise dependent on a farm’s regional grid. A 2020 World Wildlife Fund study modeled the environmental impacts of lettuce grown hydroponically in St. Louis versus being shipped from California. The indoor lettuce used less water and land, but had higher greenhouse gas emissions — even factoring in nitrogen fertilizer use and transportation.

How much more energy these farms use depends on what particular mix of technologies are being used: LED lighting, cooling and heating, water pumps. A 2021 industry survey by indoor farm consultancy Agritecture found that vertical hydroponic farms were using eight times more electricity per kilogram of food than sun-dependent greenhouses.

Large vertical farming companies remain a black box in many ways. Proprietary elements — genetics, growing technology, and other “trade secrets‘’ — abound, making it hard to fully assess the environmental benefits and drawbacks of each farm. Even 70% of growers in the Agritecture survey said they believed the industry was “susceptible to excessive greenwashing.”

Planting 500 trays a week indoors is like “regular farming, sped up.”

Small urban vertical farms are a mix of soil and hydroponic outfits, although most shipping container farms are hydroponic. Both Area 2 and Little Wild Things are soil-based, although the latter uses a hydroponic system to grow edible flowers. Neither said electricity is a major cost for them, in part because of what they’re growing and how they’re doing it.

At Area 2, Potter explained, each silo rotates the crops upward throughout the day, then drops them down to two layers without lights, mimicking a day-to-night cycle.

“It’s just like your house: Your basement is cold and upstairs is warmer,” she said, adding Area 2 only controls the temperature in one area. “We’re cutting down so much cost by just lifting it up and using natural heat rising.”

The small farms’ business models are also different from the warehouse vertical farms. Each of the D.C. businesses have a different approach, but they don’t sell to grocery stores, even ones looking for local vendors.

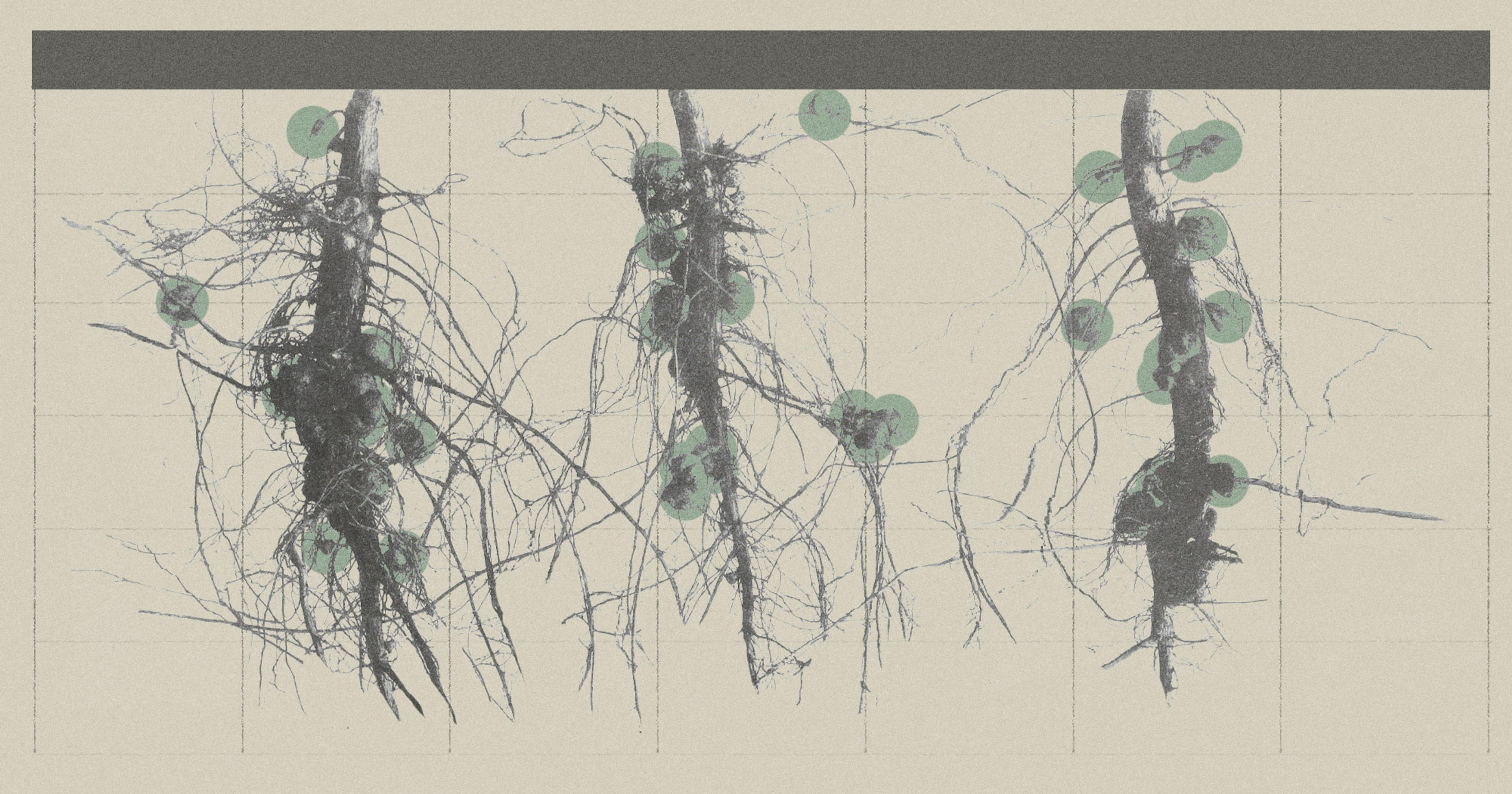

Area 2 only sells through a CSA and grows in rotations that mimic traditional seasons: items like fresh tomatoes and basil in the summer, root vegetables and bok choy in the winter, plus greens year-round. Their model was built in response to what its lead grower, Tyler Baras, experienced working at other indoor farms.

Growing “hundreds and hundreds” of heads of butterhead lettuce and selling it to grocers like Whole Foods for 10 cents of revenue a head was “not a profitable system for the farmer at all,” Potter said. Instead Area 2 eschewed investment into mass hydroponic systems — but also monocropping and harvesting enough of the same produce each week required to sell to grocers.

“Now that the bad years are gone … a lot of people are moving in and buying land, and they’re going to displace those farmers.”

“The reason why we don’t go to grocery stores is the whole point,” she said. “We’re growing so many different varieties of things and in a smaller quantity.”

That variety is somewhat of an outlier in the industry. The Agritecture report indicated not even a third of vertical farms grow something other than greens, microgreens, or edible flowers. This especially seems to be the case for smaller urban ones.

Fresh Impact, a hydroponic farm wedged between a massage spa and a halal supermarket in a strip mall on one of Arlington, Virginia’s busiest roads, sells microgreens and flowers almost exclusively to restaurants — their client list is a who’s who of D.C.’s most well-known and celebrated places to eat. Other small vertical farms located around the U.S. — in cities like Detroit, Phoenix, and Boston — are exclusively greens-focused.

It’s here that small urban vertical farms start to overlap with their outdoor cousins. Economically viable farms in urban areas without other revenue streams often have to rely on high-value, quick-succession crops like salad greens to make up for their small size, a 2019 Cornell report by Anu Rangarajan and Molly Riordan found.

Little Wild Things can’t give up part of their limited space for months in order to grow tomatoes, Gallahan said, nor do they have intense enough lights to replicate the summer sun. The quick turnover does allow them to be responsive when certain crops aren’t selling well, farm manager Gallahan said. Planting 500 trays a week indoors is like “regular farming, sped up.”

Their business model has shifted out of necessity as well. Little Wild Things launched a CSA only after the pandemic lockdown, when the Dupont Farmers Market was suspended indefinitely. But their CSA has been losing customers.

“If there’s a pandemic, a shock, a natural disaster, our food is not coming from miles and miles away.”

The farm now has a retail space inside the Union Market food hall, selling salads created with their indoor-grown microgreens. They’re hoping to retool their CSA to offer something similar: more leafy greens, carrots, and radishes.

Small vertical farms face similar economic pressures as their outdoor city siblings: balancing the availability and affordability of space with the sometimes conflicting goals of increasing food access and security for nearby residents. Specializing may help ease the financial pressures of small indoor farmers, but it limits who is interested in and can afford to buy their produce.

D.C. has long had non-profit, teaching, and community farms, well-established CSAs and farmers market vendors that have served local food enthusiasts for years. Area2’s CSA runs about $40-50 a week, while Little Wild Things’ is $30. Both are comparable in price to CSAs from outdoor urban farms or ones further afield of the city.

Many American urban farms rely on other revenue sources to be financially sustainable — farm tours, educational programs, grants and foundation support, even event rentals. The Cornell report found a significant minority of the farms they studied did not primarily rely on direct sales.

Urban farming has seen an increase in federal and local investment in the past few years. Many grants and other efforts on behalf of urban farms in the 2018 Farm Bill arrived around the same time early pandemic lockdowns exposed the brittleness of supply chains. This fueled a surge of interest in local food sources, said Vanessa García Polanco, policy campaigns director for the National Young Farmers Coalition.

“How can we bring about any amount of food security? I think that’s where this type of farm becomes really attractive.”

The USDA has also opened a raft of county committees specifically for urban agriculture, including indoor farms. But the expansion of urban agriculture in U.S. cities is hugely dependent on local factors, Polanco said, especially city ordinances.

She points to Detroit as a good example of where local government efforts encouraged urban farmers, seeing them as an asset in a city with lots of open land. But she sees potential trouble ahead.

“Now that the bad years are gone … a lot of people are moving in and buying land, and they’re going to displace those farmers,” Polanco said.

Little Wild Things itself has hopscotched across the city, including a spot near Union Market, before extensive redevelopment there made the rent unaffordable.

Vertical farms can go places that outdoor ones can’t, and some pitch this as a win-win for urban spaces in need of a post-pandemic lifeline after. Arlington County, dealing with an office vacancy rate north of 20%, recently rolled back rules preventing vertical farms, among other things, from operating out of office spaces.

But Fresh Impact’s owner, Ryan Pierce, doesn’t think his industry is going to be a quick solution for high office vacancy rates.

“How can we bring about any amount of food security? I think that’s where this type of farm becomes really attractive.”

“Offices are designed for people. Right?” he told a local broadcaster. “Making something comfortable for people is totally different from making something comfortable to essentially manufacture plants.”

For Polanco, urban farms are speaking to the need for a more redundant food system. “If there’s a pandemic, a shock, a natural disaster, our food is not coming from miles and miles away,” she said. “For me, it’s a matter of resilience.”

Despite being indoors, Little Wild Things and Area 2 see themselves as part of the local farm community. As some larger vertical companies begin to stumble with unhappy investors, the future of smaller operations may be more tied up with nearby outdoor farms than the indoor farming industry at large.

“When you look at urban spaces, you say, “Okay, how can we bring about jobs in the agricultural sector?” Gallahan said. “How can we bring about any amount of food security? I think that’s where this type of farm becomes really attractive.”

She knows her farm can’t grow everything, and thinks partnering with other urban farmers is one way to expand what they do.

“I want to know the other farmers. I want to know what their struggles are. I want to share resources. I want to share networks. I want D.C. food to be as local as it can be.”

Clarification: An earlier version of this story quoted a source who misstated both the revenue and the name of the buyer in Tyler Baras’ experience growing lettuce for other indoor farms.