As the use of H-2A guest worker visas has skyrocketed, so has resistance to regulations that would protect this workforce.

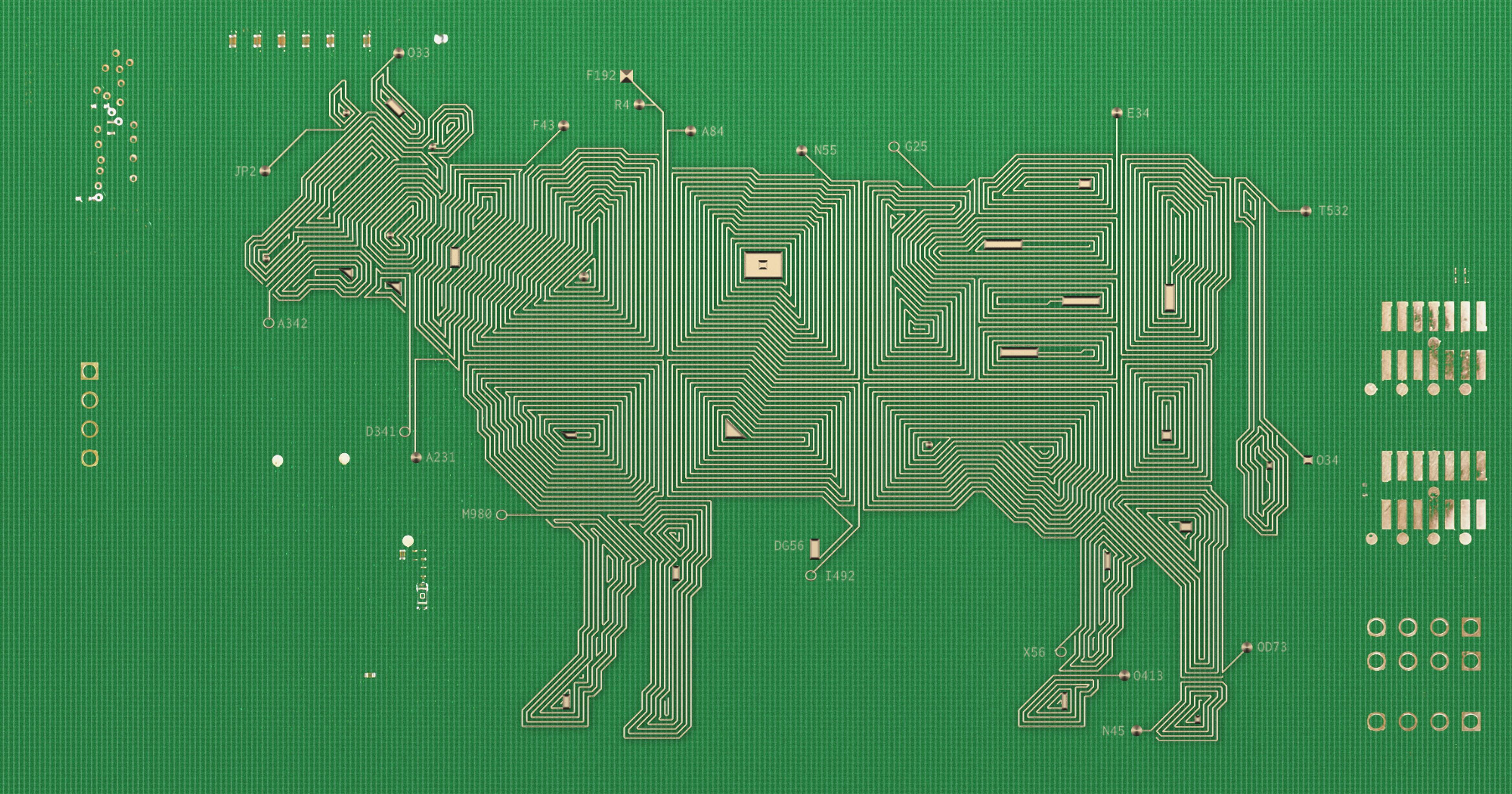

In April, a host of new protections were extended to agricultural guest workers by the Department of Labor (DOL). The department announced the finalization of a rule designed to extend rights to temporary and seasonal workers in the H-2A visa program, which allows farm owners to hire foreign laborers after proving they’ve been unable to recruit domestic workers. Workers on H-2A visas, whose legal status in the U.S. is tethered to their employers, are particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abusive working conditions.

The rule, which went into effect in June, enacted a range of new safeguards for workers and mechanisms to hold agricultural employers accountable. Unlike private sector workers, who are protected by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), agricultural workers had no federal right to organize and bargain for better working conditions without the threat of employer retaliation. The new labor department rule aimed to change that for H-2A workers — and in doing so, extend those protections to non-H-2A agricultural laborers when working alongside peers in the guest worker program.

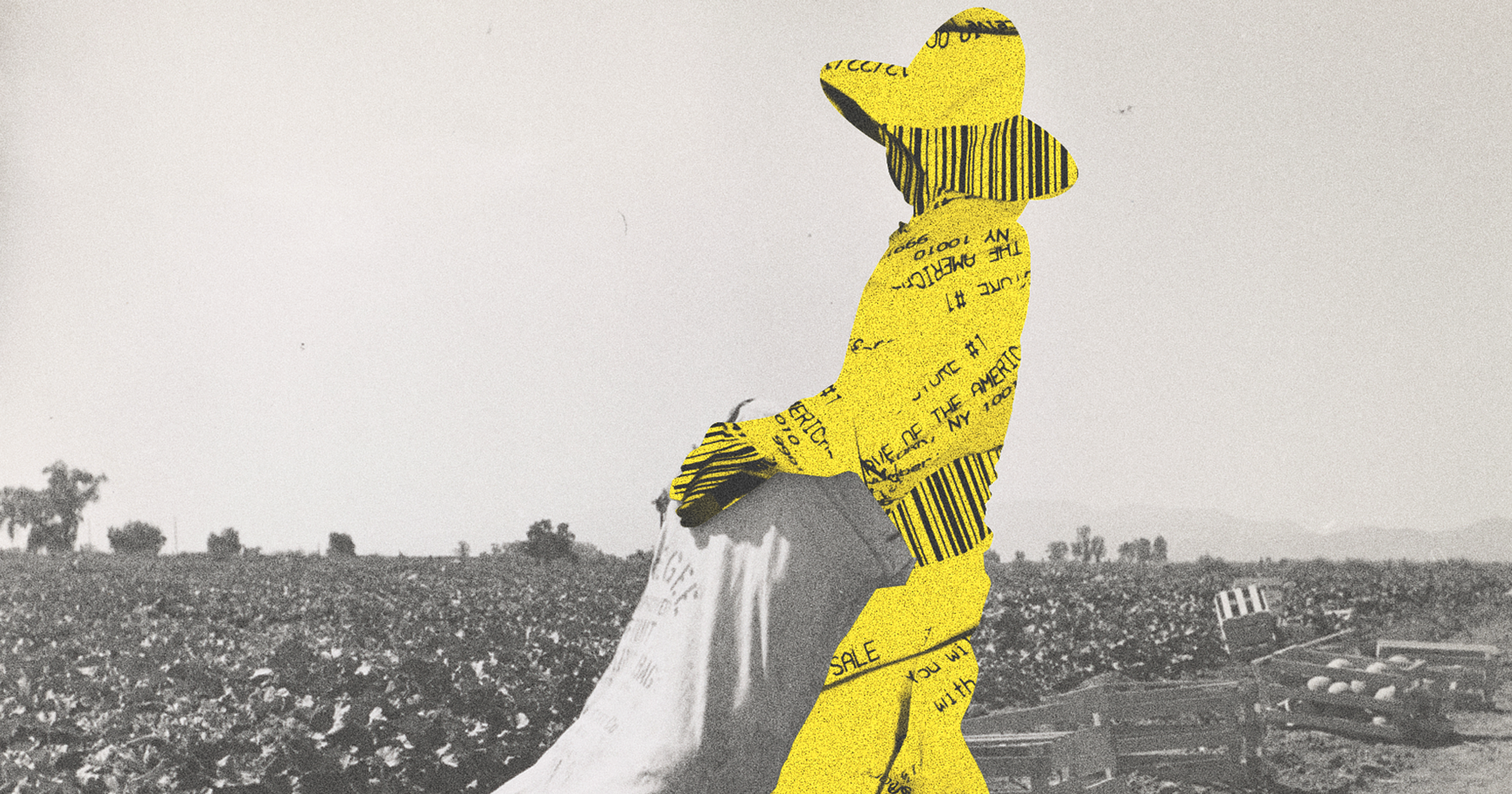

But the win for this vulnerable labor force was short-lived. In June, 17 Republican-led states sued the Department of Labor, arguing the agency had stepped outside the bounds of its regulatory power by extending labor protections to workers explicitly excluded from the NLRA. In addition to being illegal, the suit claimed, the new rule would pose undue financial and logistical burdens for farm owners. The 17-state lawsuit was quickly followed by three others, filed by farm owners and trade associations in North Carolina, Kentucky, and Mississippi. In North Carolina, the NC Farm Bureau Federation took particular issue with allowing H-2A workers to unionize.

“Farm Bureau’s farmer members believe that unions make resolving disputes with their employees more difficult, costly, and time consuming,” read the organization’s complaint. “Farm Bureau farmer members also have concerns about unions in agriculture because unions increase the cost of doing business in a local market,” they added.

As of early December, judges in three of the four lawsuits had blocked all or part of the labor department’s rule, rendering it virtually toothless. The lawsuits follow years of efforts by industry giants and lawmakers to inhibit worker protections. From limiting enforcement of protections for workers toiling in increasingly high temperatures, to blocking efforts to create new safeguards for workers, to trying to repeal overtime pay, every win for agricultural workers seems to meet a roadblock.

Attorney General Kris Kobach’s (R-Kansas) office, which led the initial 17-state lawsuit, did not respond to a request for comment.

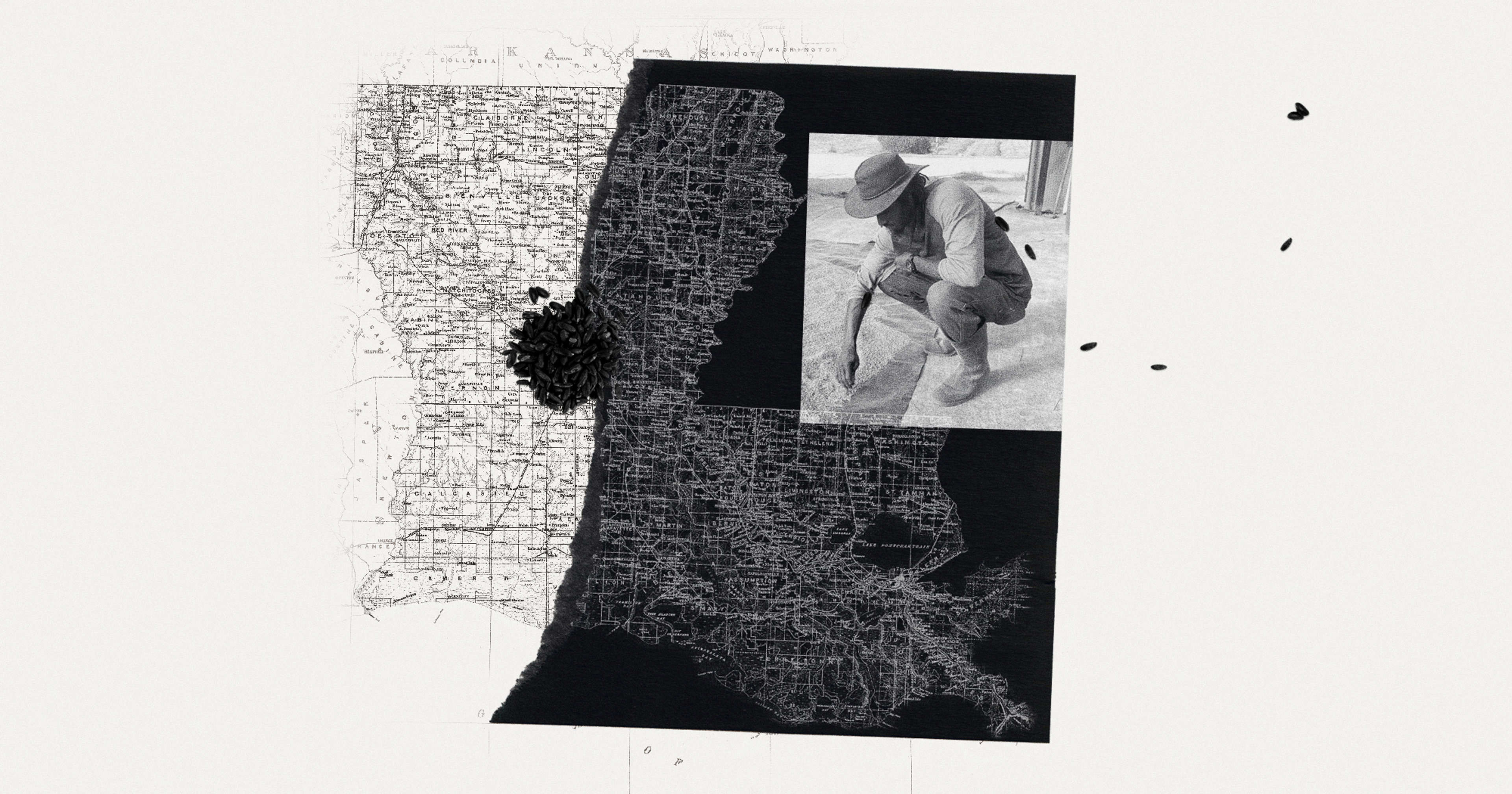

In recent years, reliance on the H-2A guest worker program by farm owners and growers has risen in tandem with harsher immigration policies and restrictions at the Southern border; advocates argue this makes the rule’s new protections all the more vital. Between 2017 and 2022, the number of H-2A workers requested by employers rose nearly 65 percent.

Beyond labor organizing, the new rule would have increased safety for H-2A workers during travel by requiring employers to provide vehicles with seatbelts, barred employers from withholding passports or visas, increased transparency in labor recruitment, and enforced adherence to a minimum wage for H-2A workers, among other protections. When the rule was announced, United Farm Workers President Teresa Romero applauded the Biden Administration for “stepping up to meet this moral crisis at the heart of American agriculture.”

The blow to the DOL’s rule is a grave disappointment for advocates who fought to protect it along the way. Nathan Leys, an attorney with the agricultural legal advocacy organization FarmSTAND, filed an amicus brief in opposition to the lawsuit from the 17 states this summer.

“Whenever these abuses come to light, the response from the agricultural industry is ‘This is a few bad apples,’” said Leys. “And rather than looking inward at their own industry to see what allows apples to go bad, the agricultural industry circles the wagons.”

“The [farm] labor shortage itself is a product of restrictive immigration policies, and a lack of path to citizenship for temporary workers.”

In a 2020 report that draws from interviews with more than 100 former H-2A workers, the migrant worker advocacy organization Centro de los Derechos del Migrante chronicled wage violations, sexual harassment, squalid living conditions, and rampant discrimination. Workers described trying to leave abusive work environments only to have their passports withheld, preventing them from fleeing. Others recounted being charged to live in horrific conditions: “I lived in a chicken pen made out of thin metal material that was in bad shape, and it had bunk beds with 30 to 40 other people,” recalled one worker.

Maria Quintana, an assistant professor of history at California State University in Sacramento who focuses on guest worker programs, pointed out that “the [farm] labor shortage itself is a product of restrictive immigration policies, and a lack of path to citizenship for temporary workers.”

The election of Donald Trump, who sailed to victory on a platform that promised mass deportations, has left some agricultural employers who heavily rely on immigrant labor uneasy. Both employers and lawmakers have urged the president-elect to exclude these employees should he fulfill the promise, pointing out that the large-scale removal of foreign agricultural workers would massively disrupt the U.S. food supply. But it remains to be seen how, in practice, Trump will navigate the tension between Republican-led states that rely heavily on foreign labor, and his proffered mission to rid the U.S. of a population that includes workers putting food on our tables.