A renaissance of centuries-old farming methods is gaining ground, but the hurdles to widespread adoption are steep.

Hawaiʻi has long faced persistent twin problems: pricey imported food and unhealthy soil caused by centuries of large-scale, industrially farmed plantations. In response, more farmers — Indigenous and otherwise — are finding the solution in a gradual return to traditional Hawaiian agriculture.

Before Europeans first arrived on the islands in 1778, “what was Indigenous agriculture was a lot more clear,” said Noa Kekuewa Lincoln, associate professor of Indigenous crops and cropping systems at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He identifies as both kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiian) and kamaʻāina, which means to be a Hawaiʻi local, regardless of race.

“You had Indigenous people growing Indigenous crops, using Indigenous agro-ecosystems,” he said. But once colonized, Hawaiʻi’s system of agriculture was replaced with a “Eurocentric model of what they thought agriculture should be.”

For European crops and ecosystems, “those systems made a certain degree of sense,” Lincoln said. But they “just don’t work” in Hawaiʻi, as the tropics are subject to higher rates of rainfall, higher levels of heat, and weaker soils.

Centuries later, Hawaiians and their lands are struggling with the repercussions of colonization. Proponents of traditional farming, like nonprofit Hawai‘i SEED, argue that industrial agriculture weakened the islands’ soil, with the sugar and pineapple plantations of yesteryear sapping it of its health.

And because Hawaiʻi imports about 85-90 percent of its food today, those products are slapped with a higher price tag than locally grown alternatives, according to the state’s Department of Business, Economic Development, and Tourism. In an increasingly expensive state, one in eight people — and one in six kids — go hungry, Feeding America reports.

The movement to embrace traditional Hawaiian agriculture aims to address the problem of overpriced imports and food insecurity, while repairing the land, growing staple foods, and rebuilding a sense of community through farming.

Historically, agriculture “was the common practice that everybody did,” Lincoln said, “whether you were a canoe maker, whether you were a warrior, whether you were a chief.”

The dominant forms of agriculture in Hawaiʻi once included permanent food forests, managed agroforestry, flooded wetland systems (similar to rice paddies), and intensive dryland systems. Native Hawaiians utilized different agricultural practices, depending on the area’s ecosystem.

Historically, agriculture “was the common practice that everybody did, whether you were a canoe maker, whether you were a warrior, whether you were a chief.”

“Arguably, Hawaiʻi is one of the most ecologically dense locations on the planet,” Lincoln said. “You go a half mile down the road, and you’re in a whole different ecosystem and you have to do something different to grow food.”

In some sense, it can be difficult to even define traditional Hawaiian farming. For instance, an Indigenous person might grow kale — a non-native vegetable — using Indigenous methods or, alternatively, grow the Hawaiian root vegetable of kalo, or taro, but rely on fertilizers and pesticides. Lincoln’s working definition of the present-day version of traditional Hawaiian farming involves stewardship of the ʻāina (land), protocol and traditions, but, most importantly, community.

That’s a far cry from the approach that American businessmen took throughout the 1800s in setting up fruit and sugar plantations on Hawaiʻi, according to the Library of Congress.

Well before the U.S. annexed the islands at the turn of the 20th century, the first sugar plantation established by foreigners opened in 1835 in Kōloa, Kauaʻi. Although pineapple isn’t native to the islands, the crop came to define the Hawaiian economy, with James Dole shaping the industry after he started the Hawaiian Pineapple Company in 1901 — the predecessor of the Dole Food Company.

“Large gang ploughs and caterpillar tractors were set to work 24 hours a day, turning hundreds of acres of soil and preparing it for planting,” Richard Hawkins wrote in The Hawaiian Journal of History. “Water was distributed through an elaborate pipe system.”

In 1961, Daisy Akuna Goodall, now 82, picked pineapples in the Dole plantation’s fields as a seasonal worker. On summer mornings, she and her sister Mary would join an all-female crew harvesting the fruit.

They’d don goggles and gloves to protect their hands from pineapple needles. By the end of her shift, a truck would brim with the fruit. Dole paid Goodall around $3 per hour, and she’d clock four to five hours daily.

The value of Hawaiian lands are “basically tied to their development potential.”

But “it’s not hard work,” she said. “Taro patches are hard work.”

Born in Keʻanae, a village in the Maui countryside, Goodall and her 14 siblings — all kānaka maoli — would work with their parents, farming their personal kalo patch traditionally. They’d plant taro huli, or cuttings, in a patch similar to a rice paddy.

After some time and care, the family would harvest the root, then cook it in an outdoor fire pit. Once cooled, they’d peel it, scraping the roots off with the shells of ʻopihi (a mollusk). Finally, they’d grind it into poi, a starchy paste and staple food.

Lincoln notes a recent, albeit “slower” revival of traditional farming. He attributes that gradual pace to financial reasons, with labor and inputs generally costing more than more modernized techniques.

Land access is another perpetual issue for aspiring farmers and Indigenous people. Because the value of Hawaiian lands are “basically tied to their development potential,” they’re often worth less for farming when compared to building a hotel, Lincoln said.

“You’re basically pitting agriculture against the most extractive and capital-intensive forms of money-making,” Lincoln said.

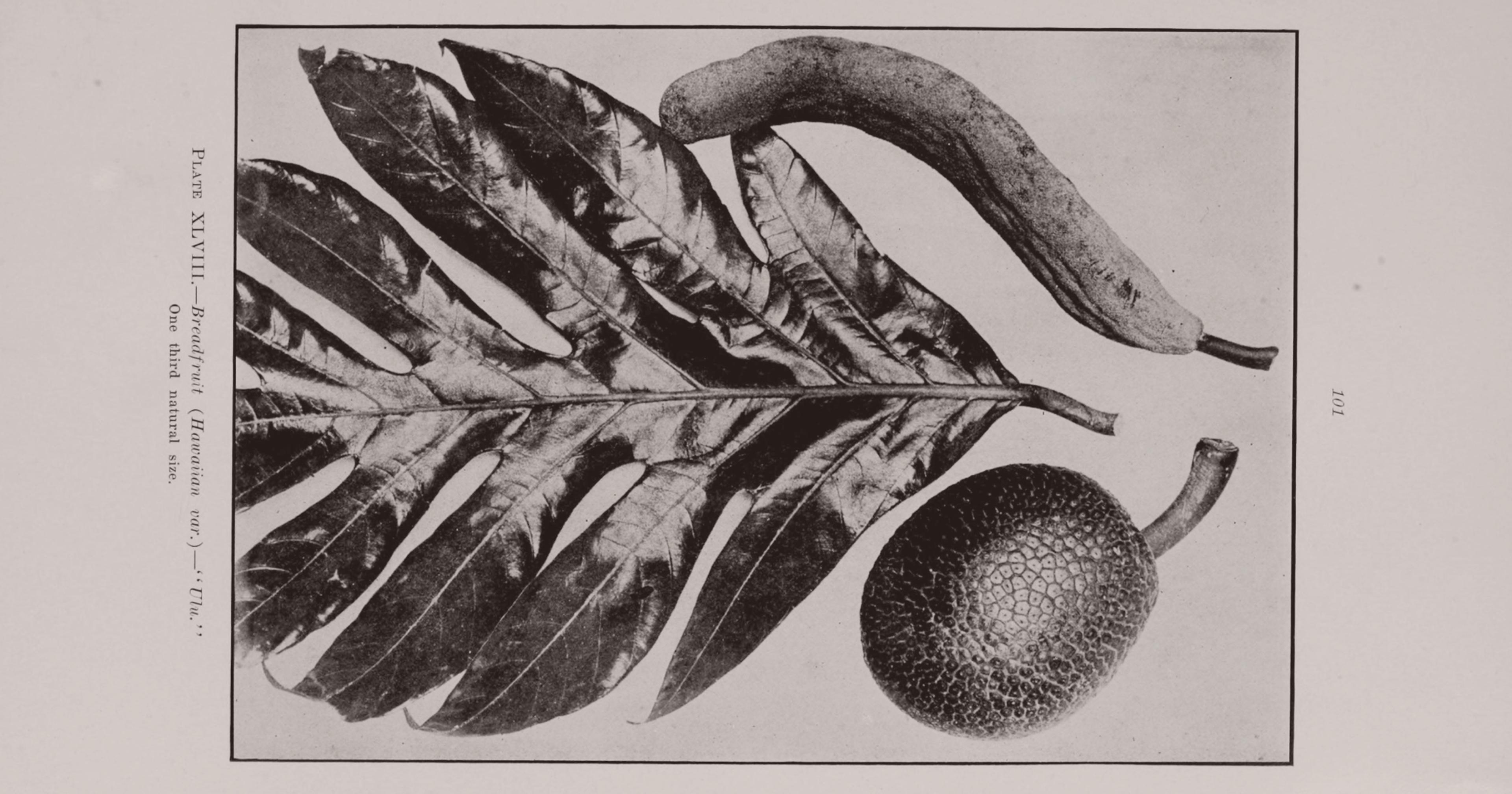

Lincoln and his wife Dana Shapiro farm the native crop of ʻulu, or breadfruit, at their 3.8-acre farm, Māla Kaluʻulu, in South Kona on Hawaiʻi Island. The couple’s farm is designed as a restoration of the historic kaluʻulu, the area’s ancient breadfruit belt, and it relies on Hawaiian agricultural methods.

“The way you gotta feed a nation is teach them how to grow their own food.”

Although Shapiro isn’t kanaka maoli or kamaʻāina, she recognizes that “it’s valuable to have living examples of these traditional cropping systems.” Instead of relying on chemical fertilizers, pesticides or herbicides, “we’re just using what’s on the land.”

After she and Lincoln started Māla Kaluʻulu in 2015, they ran into challenges like lower initial yields, invasive pest pressures, and the seasonality of their main crop. The farm hasn’t yet reached its goal of profitability.

But in 2016, the Hawai‘i ‘Ulu Cooperative was born, with nine founding members and two goals: “To revitalize ‘ulu as a viable crop and dietary staple in Hawaiʻi, and, then, ultimately, to increase Hawaiʻi’s food security,” Shapiro said.

The co-op aims to provide its producers with a guaranteed market and stable prices. It sells ‘ulu wholesale to schools, hospitals, restaurants, and other customers. They compete with imported starches like rice, potatoes, and bread.

Robert H. Pahia of Hawai‘i Taro Farm in Wailuku, Maui, started growing kalo 33 years ago, although he swore “that was the last thing I wanted to do” as an adolescent growing up in a kalo-farming community in rural O‘ahu.

But he and his wife Juanita were drawn to the crop as a way to build food sovereignty and security among Hawaiians. His mission as a kanaka maoli farmer is to educate others on growing their own kalo and to make poi more inexpensive for Hawaiians, who often turn to rice as a substitute.

“Our people over here on the islands cannot afford to eat our Native food,” Pahia said. “They’ve been priced out of even our cuisine.”

“As a society, we’re trying to re-educate ourselves on what an ʻāina-based way of understanding agriculture looks like.”

He started farming with a “conventional” mindset, but has transitioned to regenerative agriculture, foregoing synthetic fertilizers and herbicides. Pahia notes that regenerative models follow “basically the same principles” as traditional Hawaiian agriculture.

Pahia is experimenting with no-till farming, but currently plows the majority of his production. He grows several varieties of kalo, planting at least once a month — usually a dozen 300-foot rows at one time, with 200 plants each.

But it’s an uphill battle for farmers, as they compete with the tourism industry and military for water and land access, Pahia said. He points to a lack of political will to financially support local producers.

“They subsidized sugar and pineapple [industries] for so many years, and, yet, do you think they subsidize the local ag industry?” Pahia said. “No, they don’t.”

But he’s been happy to notice a jump in the number of small farmers. He said Hawaiian youth are also showing enthusiasm for the profession and its dedication to aloha ʻāina (love of the land).

“The way you gotta feed a nation is teach them how to grow their own food,” Pahia said.

Ethan McArdle works as the farm operations manager at Ho‘okua‘āina in Kailua, Oʻahu — an organic farm and nonprofit that mentors youth, striving to reconnect its visitors to the ʻāina. The farm grows kalo as its main crop, but also produces ‘ulu, bananas, cacao, and more.

He credits Hawai‘i’s younger generations with furthering the movement to return “to the land,” even when the opportunities to do so are slim.

“It’s really expensive to live in Hawai‘i, and to afford land is extremely difficult,” said McArdle, who’s kamaʻāina without kanaka maoli ancestry.

“As a society, we’re trying to re-educate ourselves on what an ʻāina-based way of understanding agriculture looks like,” McArdle said. “It’s a constant learning process for everyone.”

Author’s note: Megan Ulu-Lani Boyanton is kanaka maoli, and her grandmother is Daisy Akuna Goodall.