Multigenerational winemakers want to continue the legacy of old Zinfandel vineyards, but economic pressure poses significant challenges.

Janell Dusi could sum her routines into three words: pick, prune, and press. Outside her childhood bedroom window in Paso Robles, California, rows of old grapevines that her great-grandfather planted are lined up like soldiers in a ceremonial parade. For four generations, the Dusi family, who immigrated from Italy, has tended, harvested, and sold Zinfandel grapes to local winemakers in California. As a kid, Dusi would beg her grandfather, Dante Dusi, to teach her how to make wine. She’d later become the first winemaker in her family, with a wine label that carries their name.

As the wine market shifted in favor of more popular varietals, keeping the old vineyards going can be challenging — both financially and practically. But Dusi, along with a fiercely dedicated array of California grape growers, is not letting these challenges stand in her way.

Zinfandel’s Tangled History

Zinfandel is a grape variety with a complicated American past. “It is the only grape in California that had any trial by fire,” said Joel Peterson, founder of Ravenswood Winery, who has been growing and making Zinfandel wine since 1976.

The grape has a Croatian origin, and made its way to the United States in the 1830s. In the 1800s, when a virus called phylloxera wiped out most vines in the U.S., Zinfandel was the first to be replanted on a virus-resistant St. George (Vitis rupestris) rootstock. By the 1880s, it was the most planted grape in California. The grape saw its glory days during the Prohibition era in the 1920s, around the time Sylvester Dusi, Janell Dusi’s great-grandfather, planted his Zinfandel in Paso Robles.

When the government banned commercial wine, growers shared their supplies with home winemakers who continued to produce and enjoy them legally. Apart from surviving shipment, Zinfandel grapes, “had the flexibility to be able to be planted in a number of places and still produce good terroir-driven wines, wines that had a specific flavor of place,” said Peterson, who serves on the board of directors at Zinfandel Advocates and Producers.

After the Prohibition era, Zinfandel’s popularity waned.

Cabernet Sauvignon Takes Over

Zinfandel wines produced from old vines are known for their bold red color and flavors that burst with hints of berries and plums, topped with a toasty, peppery finish. But while its exuberant taste draws people in, few would place it at the caliber of high-end, luxurious wine varieties.

“I think that somehow familiarity breeds contempt,” said Peterson. Post-Prohibition, Zinfandel was made into ‘jug’ wine that didn’t sell for much money and wasn’t highly regarded. “It was the grape that got lost in part because it was so functional. People thought of Zinfandel as a Volkswagen as opposed to a Cadillac,” Peterson said. “And it never entirely recovered from that.”

Over time, Zinfandel’s reputation was eclipsed by Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, which came to California from France with high-end reputations. The two cultivars earned Napa Valley its global recognition as a premium wine destination after winning an important wine contest in France in 1976, dubbed the Judgment of Paris.

“There is a little quip that we used to say: Cabernet Sauvignon is king, and Zinfandel is the prince that will never become king.”

“There is a little quip that we used to say: Cabernet Sauvignon is king, and Zinfandel is the prince that will never become king,” said David Gates, senior vice president of Ridge Vineyard. Ridge has been making Zinfandel wine since the 1960s, some of it using grapes sourced from the Dusi family vineyard. For decades, Ridge has prided itself on making individual wines from individual vineyards across California. “Why Zinfandel for us? Because we’re making wines that showcase the place and that’s what Zinfandel is really good at, especially when you find some older vineyards.”

While Ridge is a primarily Zinfandel-focused winery, they also make other wine varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon. “It is difficult to sell Zinfandel at a price as high as Cabernet — that is our [eventual] goal.”

Only those who can set their bottle prices could afford to keep an old Zinfandel vineyard, said Jason Mikami, a winegrower in Lodi. But that’s not a luxury everyone has.

Since 2006, California has lost about 20,000 acres of its Zinfandel vineyards. The exact opposite was true for Cabernet Sauvignon. In 2022, a ton of Cabernet Sauvignon was sold at an average of $1,955, almost three times higher than Zinfandel, according to a USDA report.

Zinfandel dwindles. Data of grape bearing acreage in California based on USDA data.

Mikami, who grew up at a vineyard that his family has kept since they emigrated from Japan in 1896, had to sacrifice some of these century-old vineyards. When his father died in 2005, he tore down all the old vine Zinfandel and replanted them with younger vines for greater yield. “It was a really tough decision for us,” he said. “I wish I still had those old vines because it’s hard to beat the quality.”

Bruce Fry in Lodi shared Mikami’s sentiment.

“We don’t really want to do it,” said Fry, a winegrower at the Mohr-Fry ranches in Lodi, California. Over the years, he’s torn out 50 acres of old vine Zinfandel in his vineyard to grow Sauvignon Blanc, a higher-priced grape.

“It just comes down to economics and if the dollars and cents don’t compute for the old vine Zins then you got to do it,“ he said ”In the end, you got to make money.”

Tending the ‘Geriatric Ward’

Vineyards are now typically replaced when their productivity dwindles — usually at around 25 to 35 years. Some “old vines” refer to grapevines more than 35 years old, others older than 50. Because of their age and anatomy, these older vines require extra patience and skills to maintain. As a result, hundreds of acres of these century-old vineyards are ripped out each year and replaced with more productive and profitable varieties.

“An old vineyard is like a geriatric ward,” said Mike Officer, recently retired winemaker and grower in Sonoma County who co-founded the Historic Vineyard Society, a non-profit dedicated to preserving old vineyards. “Every vine is its own individual patient with its own individual needs,” he said. Yet despite the challenges, “these vineyards produce incredible wines. And I think it would be a great loss to consumers and wine aficionados to lose these vineyards.”

Unlike most modern grapevines, old vine Zinfandel is head-trained, which means they stand freely without the support of a trellis. They have short trunks with arms that spread in different directions, forming a goblet shape. Because of their gnarly architecture, growers usually hand-prune their spurs, often bending their backs over for hours. Meanwhile, most modern trellis vines can be easily machine-pruned.

A Zinfandel vine at Dusi's property in Paso Robles

·By Kristel Tjandra

The way old vine Zinfandel grows also causes their grape clusters to hang at varying heights and sun exposure. Hence, their fruits don’t ripen evenly. When the harvest comes, the berries or raisins vary in size and plumpness, producing fruits with a hodge-podge of acidity and sweetness.

“That makes people nervous about Zinfandel,” said Dusi. Not to mention, changing climate and rainfall patterns always keep growers and winemakers on their toes. “Mother Nature just brings us something different every year,” she said.

Zinfandel’s Hidden Treasure

Morgan Twain-Peterson, son of Joel Peterson and owner of Bedrock Wine Co. in Sonoma, California, sees a real learning opportunity in tending the old vineyards. He noted that while economics could thwart the survival of old vines, sustainability may be its saving grace. Most old vines were planted with dry farming in mind, meaning the vines relied solely on soil moisture or annual rainfall and no irrigation. Compared to younger vines, old vines are usually more spaced out to allow more airflow and roots to deepen, and a larger area for the plants to draw moisture and nutrients.

“A lot of modern vineyards have been put in with the expectation of water availability,” Twain-Peterson said. “The problem though, is that in a state like California, where historically we’ve always had drought events, if the water goes away, those vines die.”

“With Zinfandel, you’ve got something that we make in California that no place else makes in the world.”

Many commercial grape varieties are also prone to powdery mildew infection, necessitating the use of fungicides like sulfur. In 2022, sulfur was the top pesticide used in California by pounds. “The problem is sulfur dust absolutely destroys soil structure,” he said. Over-acidified soil due to excess sulfur could introduce stress to plants that interrupt photosynthesis. But powdery mildew is not a threat to Zinfandel; no sulfur is needed.

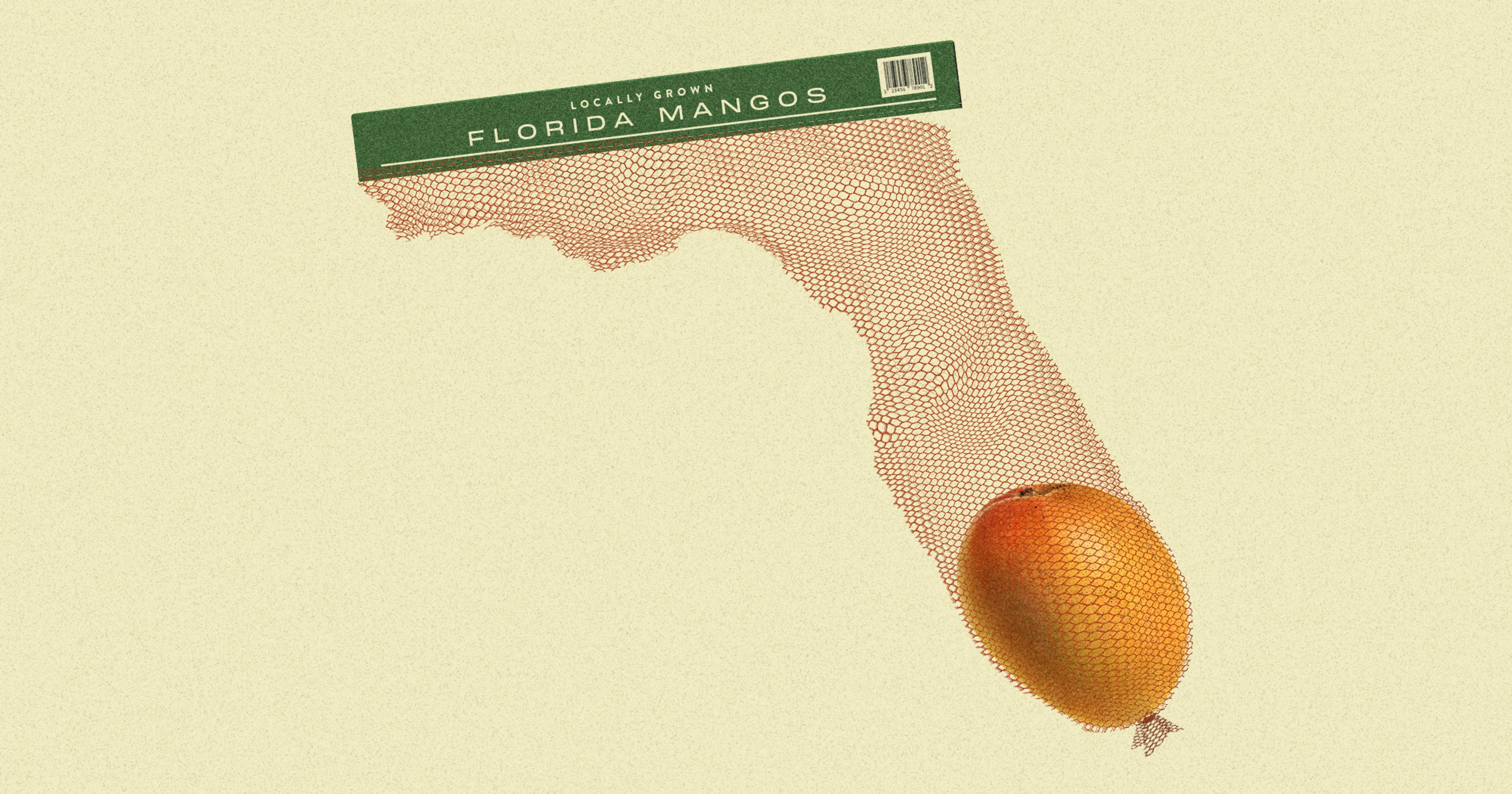

But despite its hardiness, Twain-Peterson believes the main value of preserving old vine Zinfandel lies in its history and heritage. “Bordeaux has always been the reference point for Cabernet. The northern Rhone is the reference point for Syrah. With Zinfandel, you’ve got something that we make in California that no place else makes in the world,” he said. Because of this, Zinfandel is often referred to as the American heritage wine.

Twain-Peterson also appreciates the genetic diversity that old vines carry. In his vineyard in Sonoma, Twain-Peterson has found more than 60 different grape varieties, “some of which have no matching genetic fingerprint, which means they’ve likely been lost — where they originally came from — or that they are extremely rare and nearly extinct. That makes them really interesting.” Preserving old vines is therefore akin to conserving this rich genetic diversity that could increase the overall value of wine.

Continuing the Legacy

This year the Dusi family celebrates 100 years of winemaking in Paso Robles. For Dusi and other growers, the solution to keeping these old vineyards is straightforward: “We keep them alive and thriving by caring and not replanting them,” she said.

Janell Dusi

·By Kristel Tjandra

As winter arrived, Dusi prepared the old vines for pruning. She looked forward to spring, her favorite time of the year. “When the buds break, you can just watch them grow overnight. It’s miraculous,” she said.

As she walked towards her winery, a young man entered with his boots.

“That is my nephew,” Dusi said. “He’s 21. He lives and breathes the vineyard and is obsessed with it. I trust him with my life on the tractor compared to me driving.”

And his name? “Dante — Dante Dusi.”