Giving workers a slice of the pie has proven to increase production and solve labor shortages — can it be replicated in other sectors of agriculture?

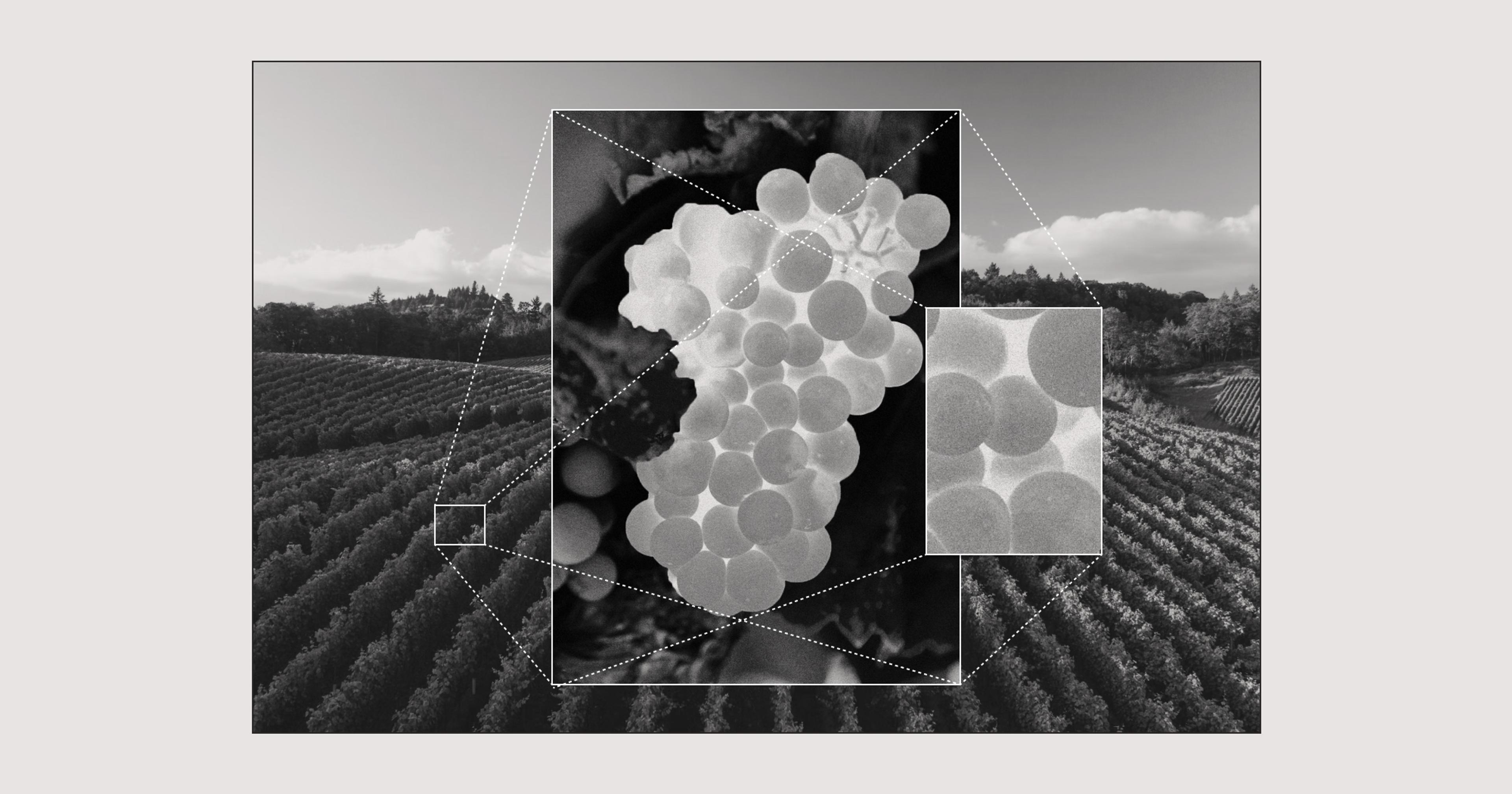

Vineyard Manager Ruben Solarzano decided to try an experiment with his workers at Stolpman Vineyards in Los Olivos, California. He gave his crew of 15 a two-acre plot of vines to completely manage by themselves.

Though Solarzano was always happy to answer questions or offer advice when asked, the crew made every farming decision on the block: how to prune and shoot thin, when to vertically position the vines, whether to drop fruit. The employees did not earn extra income from the project, but they did become far more engaged in their work. “Ruben saw an immediate difference,” said partner Peter Stolpman, who took over operations from his father Tom in 2009. “The crew not only took way more pride but became more engaged about the entire vineyard.”

Two years after starting this worker-managed project, Solarzano’s boss Tom Stolpman was lamenting that they were the only two employees drinking the wine they at a company barbecue. At that time the crew mostly hailed from Jalisco, Mexico’s tequila capital, and had limited exposure to wine culture. Solarzano decided it was time to tell Tom about the initiative and offered an idea — what if we made wine from that block as a gift for the workers who tend to those grapes?

In 2003, Stolpman bottled its first vintage of La Cuadrilla, named after the Spanish word for the small block run by the workers. That year, they produced 300 cases of wine as a gift to the 15 full-time employees — far too much wine for them to consume with friends and family. The next vintage, Tom and Solorzano decided to split up those cases, giving some to the employees to drink and selling the rest to fund a cash bonus. Two decades later, what started as a small year-end bonus has since morphed into a full-on profit-share that returns 10% of all the company’s profits back to its farming team.

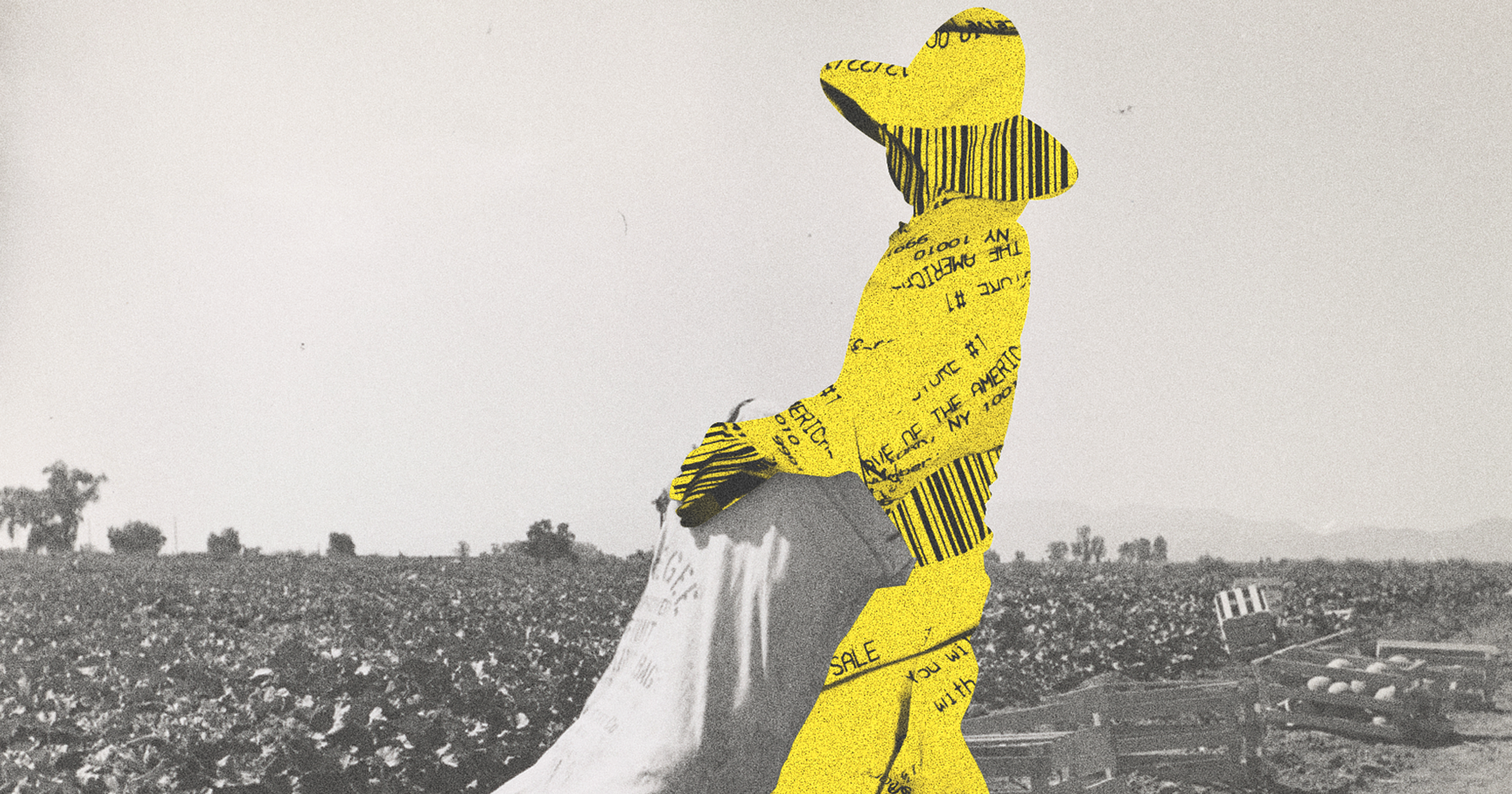

Profit-sharing is still far from the norm in the wine industry — and agriculture, generally — a sector that is notoriously asset-heavy, cash-poor, and has long relied on a low-paid migrant workforce to turn a profit or just break even. It can be challenging for many wineries to implement; however, various forms of the profit-share concept have been on the rise among enterprising companies that have the available resources — and will — to share dividends with their workers.

In Santa Barbara County, Grassini Family Vineyards gives back a portion of the profits from its Equipo Red Blend to its farming team. Turley Wine Cellars and Trinchero Family Estates in Napa Valley contribute a share of its profits to employee retirement funds. And in South Africa, Chris and Andrea Mullineaux have opened up an entirely separate employee-owned wine brand for the workers.

These wineries are joining a larger economic wave that’s been growing in many industries since Japanese-run manufacturing multinationals like Nissan began moving toward team production models in the 1980s, according to Harvard Business Review. Crop share leases with hay and grains, like corn and wheat, where the landowners and tenants split farming expenses and profits, have existed for decades. And employee stock ownership plans have been slowly growing among diversified vegetable farms. But profit sharing seems to be particularly taking off in wineries, giving other agriculture sectors a potential model to look toward.

Well-executed profit-shares are helping wineries solve major crises including labor shortages, rising costs, critiques of exploitative working conditions, and cost-of-living issues faced by workers earning meager salaries in some of the most expensive places to live in the United States.

“We want to put our money where our mouth is. We have the best crew and they need to get paid for it.”

Studies have consistently shown that employee share ownership plans tend to garner more loyalty and longevity as well as increased yields. “We are highly confident that profit-sharing companies have higher average productivity,” said Douglas L. Kruse, acting director for Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing at Rutgers University.

For the first five years of La Cuadrilla’s production, Stolpman’s vineyard workers were earning an average $500 in bonuses per year. The amount wasn’t huge, but combined with the company’s commitment to only employ full-time workers — a stark contrast to the migrant workforce that has long been common in the wine industry — they were able to maintain a loyal, steady crew.

This continuity has been a huge boon to the company, which produces 25,000 to 30,000 cases per year from its estate and another 25,000 to 30,000 cases from outsourced grapes. They’ve never faced the labor shortages that have become an increasing problem in agriculture and the larger economy.

Stolpman’s team meticulously prunes, thins shoots, and hand-picks 174 acres of vines on the estate. This keeps the plants healthier and productive decades longer than the 15 or so years many other vineyards are able to get out of their vines before having to replant and start over. “We have people who care about our vines and can see potential problems to fix them on the fly,” said Stolpman. “We literally have 34 viticulturalists out in the field every day.”

If these employees choose to move on, their extensive training at Stolpman Vineyards will help them land well-paying jobs in the wine industry. However, the supportive workplace culture that allows them to engage in problem-solving to bolster their immediate income makes staying at Stolpman far more attractive. These factors are integral to a successful employee share ownership plan, said Joseph Blasi, the J. Robert Beyster Distinguished Professor at Rutgers‘ School of Management and Labor Relations: “You can’t expect people to be motivated by profit-sharing if they have no involvement in solving company problems that could affect the profit.”

“You can’t expect people to be motivated by profit-sharing if they have no involvement in solving company problems that could affect the profit.”

Through decades of research Blasi and his team have found that successful profit share plans must start with a fair base wage, a sense of job security, and be significant enough to garner employees’ attention. While many companies offer 2% to 5% shares on top of wages, the institute has found the rate needs to be closer to 10%.

In South Africa, Chris and Andrea Mullineaux’s Great Heart Wine gives back 20% of its entire sales — not just profit — directly to its 42 employees. Their concept takes the employee share ownership plan to a whole other level, giving workers complete say in an entirely separate brand that uses their existing winemaking, distribution, and marketing systems. Anyone who works for Mullineux & Leeu Family Wines for two years automatically becomes a shareholder and receives dividends from the sales once or twice per year. “In the first year some of the staff who have been with us longer than 10 years got an extra four months salary,” said partner Chris Mullineaux. “Two of the guys bought land in their villages to build homes.”

Each team, from vineyard and cellar to sales and marketing, work together to elect a board of directors who represent the various sectors of the organization and regularly meet to make decisions on all aspects of the business. Eventually, the goal is to earn enough profit from the sales that the employee-owned company can purchase its own vineyards.

Currently, land-ownership is a very contentious issue in South Africa given its long history of colonialism and apartheid that lasted until the 1990s. Most of the other winery profit-shares in the country have focused more on subdividing land for employees, which — given the difficulties of farming especially in a region prone to extreme drought — doesn’t necessarily translate into cash-flow, said Mullineaux.

Stolpman’s profit share system did not take off nearly as quickly as Great Heart’s due to a series of economic and personal hardships including banking issues related to the Great Recession of 2008 and the founder’s bout with cancer. That said, by 2018, the amount of money in the bonus coffer became so significant they began to split it up throughout the year. And starting in 2020, a $3-per-hour bonus started getting added to farmworkers’ paychecks, followed by another year-end payout. While new cars often show up closely after the post-harvest profit-sharing distribution party, the majority of workers use that extra money toward savings and helping to support their families.

“We want to put our money where our mouth is,” said Stolpman. “We have the best crew and they need to get paid for it.”