Agriculture workers could greatly benefit from proposed legislation mandating PTO during hurricanes, wildfires, and more. But who gets to take it? And who will foot the bill?

Ever since a small New York tech company offered paid “climate leave” in 2017 — a response to employees displaced by wildfires and a hurricane — the idea has slowly gained traction as a voluntary employer benefit. But after a tornado killed six on-the-clock Amazon workers last December, Rep. Cori Bush (D-MO) drafted legislation that would mandate this perk; employers would have to give paid time off (PTO) and other worker protections in the face of climate disasters.

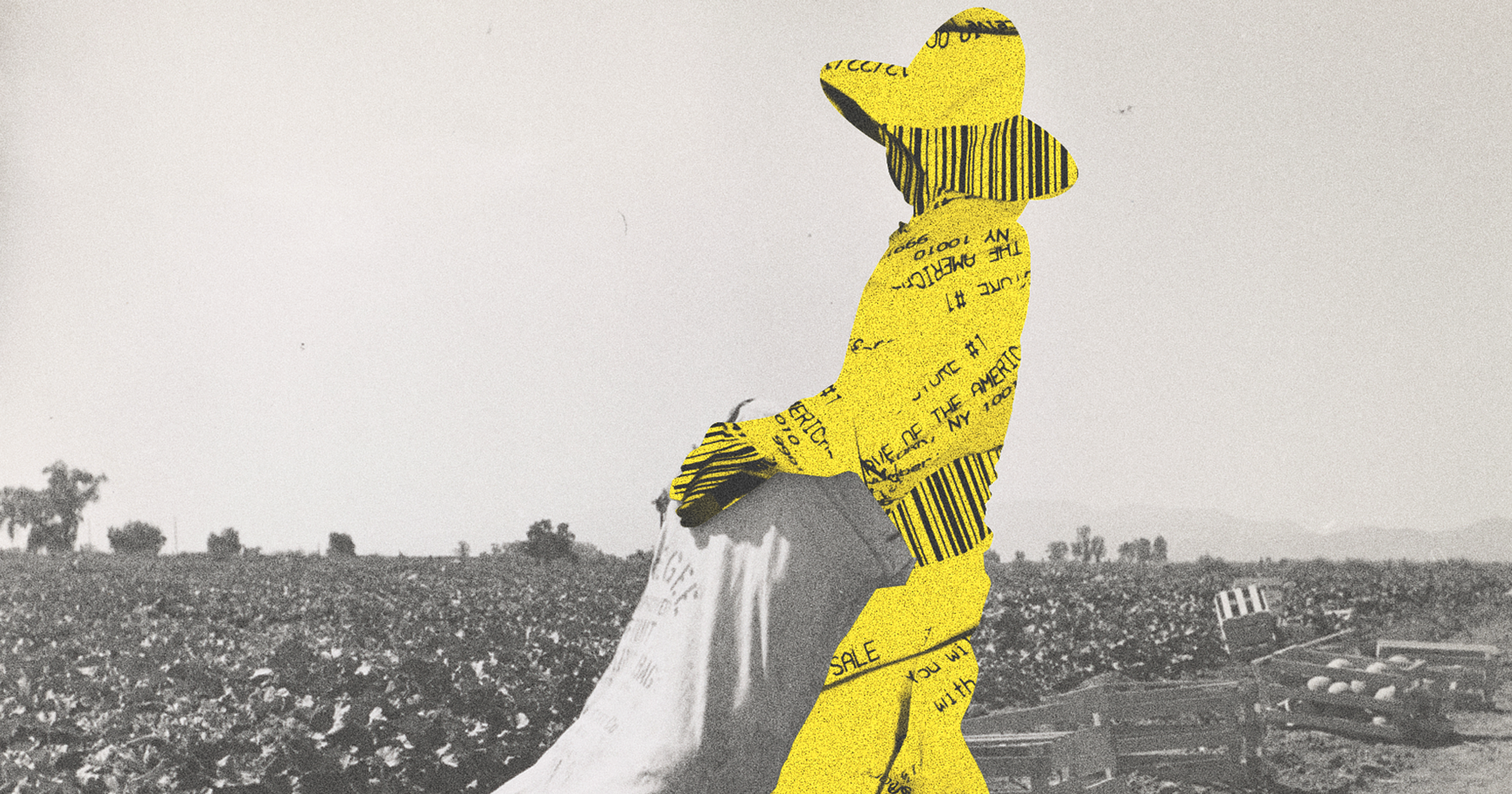

This type of employee perk is not unheard of for white-collar workers, typically clocking shifts in cushier office environs. But as the frequency and intensity of this type of disaster continues to ramp up, labor advocates are highlighting a group that would directly benefit from the proposed Worker Safety in Climate Disaster Act: farmworkers. “Outdoor work in agriculture, heavily dependent on the state of the natural environment, puts its workers in a disproportionate level of precarity,” said Lucas Zucker, policy director for Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy.

Just this fall, agriculture workers in California have contended with the latest batch of wildfires, while Florida farmworkers were pummeled by Hurricane Ian and its aftermath. If a farm owner is forced to hit pause, that typically trickles down to a lack of income for their workers. But if operations do continue, it can force workers to make an uncomfortable binary choice: keep working despite risks to health and safety, or stay home and lose a vital paycheck.

“For anyone involved in the citrus industry, whether you’re an owner or an employee or an H2A contractor, there’s not a single damn positive about a situation like [Hurricane Ian],” said Ray Royce, president of the Highlands County Citrus Growers Association, whose county sat squarely in the eye of the hurricane. “Everybody gets hit.”

“If you’re asking a farm owner to compensate a worker when the farm owner just lost their stream of income, then that’s just not sustainable, right?”

Some embattled farmers have tried to create their own version of this proposed legislation. Jim Strickland, a Florida cattle ranch owner who typically manages 10-15 employees at a time, was able to access USDA funds to assist with his farm’s recovery during Hurricane Ian. Though his margins are tight, he did not need to cease paying workers. But he acknowledges that he has been lucky: “We made damn sure everyone got paid, because they need it,” said Strickland. “But there are a lot more unfortunate farmers than this guy you’re talking to.”

Many farmworkers are undocumented and thus exempt from typical social safety nets — which means a climate disaster can be particularly precarious. That’s precisely what this proposed legislation intends to address: “As the climate crisis continues to accelerate, extreme weather and climate disasters have become more frequent and more severe, putting frontline workers and communities at the highest risk,” said Rep. Bush in a statement. “The safety of our workers, especially our most marginalized workers, should always be top priority.”

Bush also noted that “big corporations” were the main target of this legislation; it includes an exemption for businesses with fewer than 50 employees “when the imposition of such requirements would jeopardize the viability of the business as a going concern.” Considering that farm-business-as-usual would be all but impossible during a climate disaster, this particular provision could be the subject of some lively debate.

“If you’re asking a farm owner to compensate a worker for something when the farm owner him or herself just lost their stream of income, then that’s just not sustainable, right?” said Federico Castillo, environmental and agricultural economist at the University of California, Berkeley.

“A grassroots organization cannot be FEMA.”

There are other details that would need to be settled as well. Who determines what qualifies as a full-blown climate “disaster?” How would agriculture workers, many who are paid by piece rather than hourly, be compensated for days lost? Bush’s office was not able to provide details in time for story publication, but questions remain.

While some parts of the legislation still need to be hammered out in committee — and it’s far from certain that it will even pass — the bill’s intention is to cover undocumented and documented workers alike. In addition to two weeks of PTO, it mandates employers inform employees of impending climate disasters, and to not penalize workers in any way for seeking shelter or caring for family members.

“During [Hurricane] Irma, workers would take turns going to work and one family member — usually a woman — the member would stay behind and take care of the children so that they wouldn’t have to pay for childcare,” said Neza Xiuhtecutli, executive director of the Farmworker Association of Florida (FAF). But this type of stopgap measure still puts workers in danger and is not sustainable in the long-term; Xiuhtecutli noted that more government assistance is sorely needed.

As it stands, Xiuhtecutli said that his organization and other forms of farmworker mutual aid provide a minimal safety net for this vulnerable community — but that it isn’t sufficient, or sustainable, in times of disaster. Zucker, who interviewed a range of California farmworkers after the Thomas Fire in 2017 for a research study, also notes the limitations of philanthropy and mutual aid. “A grassroots organization cannot be FEMA,” he said.

But when even FEMA struggles to supply funds, it remains to be seen whether Bush’s legislation will be the long-term solution farmers and workers need. “The devil is in the details,” said Castillo.